222

Rwenzori: Historíes and Cultures of an African MountainVan Gennep,

A.

1909. Les rites de passage, (Itaiian edition 2006.1riti

di p assagio.'î

onno: Bollati Boringhieri).Notes

1. The research on which this v'ork is based was patially funded by the Nlissione Etnologica Italiana in Africa Equatoriale, directed by Dr. Cecilia Pennacini, University

of

Turin. The tìeld work was carried out with permission of the Llganda National Council for Science and Technology (File No. SS1655) and took piace in two different missions over a period totalling seven months, between May 2004 and,January 2006.Often, in my interviews, ìilomen made mention of the number seven, of said "seven plus seven" to mean a large but indefinite number of chi-ldren, ofyears, oFgoats, ecc.

As to the reason why informants are so vague about the moral stories and

instructions

to

the

youth,two

explanations seem possible: eitherinformants did not \r"'ant to share maìe initiate knowledge with me, a

woman, or the content of the stories s,as not signihcantly different from the usual moral education children teceived in the family, albeit indirectly, and thetefore was not v/orth mentioning.

In spite of all these elements of change, it is important to point out that few informants recall that the return from the Olhusurnba was a dramatic change ftom their childhood that had ended onll' a few weeks eadief, True change, statc the older informants, takes place with marriage and thc birth of children. Once again the I{onzo socieq' refuses to acknowledge change when

it

is too sharp, preferring to metabolize change through lengthier processes.In

1947 the Adventist Church, lead by two pioneering missionaries, reached Mitandi, on the slopesof

the Rwenzori. They were the fust Christian missionaries to settìe among the Bakonzo. Communication by N{r. Stanley Baluku. 5. 2. 3. 4.Contin

u

ity

Bakonzo

and Change

in

Music:

From

1906

to

200b

Serena Facci and.

Syloia

Nannyonga-To*rruza'

Music and dance,

like

anyother

form

of

cultural exprcssionr iHsubject to both continuiq'and change. \X/hile change is incvit:tlrk', there

is no

culturalformation that

changes overnightantl

itt

uwholesale mannet; some aspects are retained while othefs arc lost,

Similady, the aspects

of

the musicof

the Bakonzo, peoplc livingin

Rwenzori Mountain tegionon

the botderof

westetn tlgutttlrt and eastern Congo (now Democratic Republicof

Congo), hrrvt'experienced

continuity and

changein

the

last century

(l(){)6 2006).We

shall

look

at

continuity

and

changein

terms

ol' performance practices, the types of instruments used, the variorrs contexts of petformance, musical structure, and meaning.However,

it

is very hard, we could say impossible,to writc

ucomprehensive

"history"

of the musicin

the Rwenzori area in thepast

century.To

be

historically described,the Konzo

musicwould

need regular and intensivefieldwotk

and comprehensivc documentationabout

musical instruments, aswell

as Picturcs,audio and

video

recordings, musical transcriptions and analysis,descriptions of the context and the occasions when the music ancl the dances were performed, as well as the musicians'biographics.

In

this

paper,we

will

considerotal

evidenceand

writtcn records from the local Bakonzo'. Although these srudies^re very

far ftom

being complete, theyoffer

a

precious insightinto

the past, giving àfirde

of

local musical history against which we canpredict

the

furure.

They

are

like little

windows

opened occasionallyand

for

a

short time

onto

the

fascinating musical panoraml-of

the

Rwenzori.\(hat

we offer you

is

not

a

teal224 Histories and Cultures of an African Mountain

"history",

but

a more

modest diacbronic etbnograplry.In

fact, there are alot

of

gaps, andthis

paperonlv

aimsat

stimulating more studyof

a musical culture that has almost been forgotten.In

this paper, v/e compare the ethnographic reports, imagesand sound records

of

the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in orderto

trace the historical trendof

Bakonzo music.During

our researchin

I(asese and Bwera Districts, we made an overviewof

the

musical characteristics ancl social-culrural relations (dancemovements and

motifs,

musical instruments, music theory, roleof

the

music

in

terms

of

meaningand

performance)in

thetu/entv-fìrst cenrury.

We

ptesented

to

the

musicians

someBakonzo and Banande music documented

in

the pastin

order todiscuss

with

them the historical dimension of this music.Bakonzo

Music Context

\X/hen

Luigi

Amedeodi

Savoia,the Duke

of

Abruzzi. arrivedfrom

Italy neat the Mountainsof

theMoon

in

1906r, we can besure

that the

musical traditions wereverv

lively. However, thecultural, social

and political

contexts

that

have defined

the Bakonzo since 1906 accountfor

the continuity

and change in their musical traditions.In

orderto

establish the contextfor

this discussion, there is a needto

examinein

brief the cultural, social,and

political

atmosphereunder

which

music

has

existed.Howevet, as

John

Blackingrightlv

reminds r-rs, "changes which are characteristicof

musical systems arenot

simpiy consequencesof changes

in

social, political, economic and other^feas"4 .

There is

no

certainfy about the origin and movementof

theBakonzo

before they

settledin

the

Rwenzori region.

Somehistorians and oral traditions claim that they broke

off

from

the Batoro,while

others claimthat

they camefiom

Buganda after escaping persecutions;others

allegethat they

camefrom

the present eastern Democratic Republicof

Congor' and yet otiÌers say the Bakonzowith

the Banande (nowliving

in

Congo) werepat

of

a bigger linguistic group: the Bayira'. However, whetherContinuity and Change in Bakonzo Music: From 1906 to

2006

225they came

from

the

eastern Democratic Republicof

Congo orwere originally one

group

before they were

split

by

atificial

colonial boundaries, the Bakonzohave alot

in

commonwith

the Banandeof

the

eastern Democratic Repubìicof

Congos. First,the

languageLukonzo and

l(nande

arevery

similar, whereasI-ukonzo is quite different

from

the languagesof

thellatoro

andBanyoro

in

south-eastUganda

(Lutoto, Lunyoto).

In

fact, MargaretTrowell

has

stressedthat,

"\X/hereasin

Uganda the nameI(onjo

is in offìcial use, the name by which the same tribe is generallyknown

in

Congo

fDemocratic Republicof

Congo] isBanande"e.

The

Banande were separatedfrom

the Bakonzo by the artificial bordedines "defìnedin

a seriesof

treaties that were drawn up between 1907 and 1910, after the dukeof

the

Abruzzi had explored the Rwenzofl"10.As

such, there is no way one cantalk about the continuity and change

of

the music of the Bakonzowithout

referringto

that

of

the

Banande. Althoughwe

can seem^ny vartztions when comparing Nande and

Konzo

music, they look like natural transformationsin

a.m

tn common culture. Thehard

question

would

be

to

ascertainwhy

and when

thesetransformations happened.

Moreover,

comparisonswith

the Baganda and Batorowill

help usto

develop an understandingof

the continuity and change that shaped the Bakonzo music.Despite the strong struggle

of

the Rwenzuturu Movement to liberate the Bakonzo, until the 1980s they were under the political controlof

the Batoroof

theToro

kingdom". As

such,to

someextent, the Batoto and Bakonzo have had a dialectical influence

on

eachother's music.

Tom

Staceyreports

that,

"'Bakonjo [Bakonzo]Life

History

Research Society' hasslowly over

theyears been turned unto a political movement, the standard-bearer

of

Bakonio

'nationalism'

with the

declared

object

of

overthrowing Batoro dornination" 12.

Further,

Christianity

and

Western

education,u'ith

their ideologies about"traditional"

cultuÍe, have had an impact on theBakonzo,

like

on

many other

Aftican

cultures.

Mofeovet,226

Rwenzori: Histories and Cultures of an African Mountainalthough

a

number

of

the

Bakonzo have been converted toChristianity,

their

belief

in

ancestralspitits

still

holds.

Fot instance, Betnard Clechet reports that he "wasin

Bufuku (14,050ft)

[on

Rwenzori Mountain], andtried

to

get some information about I{itasamba [chief spiritof

Rwenzori], a porter, a ChdstianMukonjo,

with

grey

hair,

askedme

to

stop talking

about Kitasamba because he was evil and it was dangerous to taik abouthim

in

such

a

place"13.Actually dudng

our

research, Debizi Baluku, aflute

playet, alsotold

us that we couldnot talk

about Iltasamba while were near the mountains at Nakalengeio viliage. SomeAspects

of Toro

andKonzo Drums in

theEarly

Ttventieth

Century

Vittorio

Sella,the

photographerduring the Duke

of

Abruzzl's expedition,took

a

number

of

photographs depicting musical activitieswithin

the Rwenzori region but, unfortunately, he took noneof

the

Bakonzo, even thoughthe

porters duringthe

lastp^rt

of

the

expedition

were

ail

Konzo.

Although

theseinstfuments ate atttibuted

to

the Batoto, later writers, like Klaus Wachsmann (1953), have shown that the Bakonzo too have suchinstruments, although

they

mayvary

in

performance contexts, style'of

playlng

and

design.Two

of

the

Sella's pictures areimportant

for

this discussion.In

the fìrst

one,we

can seea

drummer and Sella describeshim

as"the

doorkeeper", greetinghim

at

the

entranceof

the Kababa's court at Kabarole(foro

District) (see Figure 4) 1a.Continuity and Change in Bakonzo Music: From 1906 ro

2006

227Figure

4

Vittorio Sella, "The watchman at the entrance of the eriba of a native chiefrwho greets visitors with a long and noisy guffaw and a roll of thé drums", 190d. Courtesi of theSe[a Foundation.

There is a similar drum

in

the ethnographic collectionof

the Museodi

Antropologiain

Torino.

Probably the Duke broughtit

to

Italy after his mission. The drum is the type that \ùTachsmann defines asthe

"Ugandadrum": "The

'Ugandadrum'

uses two skinsof

which

only oneis

bearen.The

second skinis

stetched acrossthe bottom

of

the drum

bodyto

hold the

lacing and isnon-sonorous.

t

..]

Bantu

Ugandadrums

ftequently have

a'broken'

profile

asif

the top parr

of

the

instrumentwere

a cylinder, put on to a conical base [...]"rs.This

type

of

drum

is

very

common,not only

among the Batoro, but alsoin

other Ugandan musical traditions, especially in Bantu cultures.In

fact, like the Baganda and Banyoro, among the Batoro the drum is a symbolof

power, signif ing the existenceof

228

Rwenzori: Histories and Cultures of an African Mountaina kingdom.

The

evidence given byvittorio

sella'sohoto

of

the drurn-at the entfanc eof

Kabarole Court is a signof

the pafticulaf toleof

this instrument, which is typicalof

courts like thatof

the Bagandaand

Banyoro.The drum

announcesthe

coming

andgoirg

of

the king and is indeed the doorkeeper. Tn_this case, this

ArnÀ

conldnot

beI{onzo,

since the Bakonzodid not

have anestablished kingdom.

Thefe is, however, information about Bakonzo drums at the

beginning

of

the

century

in

the

ethnographicnotes

of

Jan Cz"ekanolski,who

travelledin

the

area duringthe time

of

the Dukeof

Mecklenburg's expeditionin

1908.In

his ethnographic fepofts on Bakonzo and Amba cultures, czekanowski gives some dÀcriptions and drawingsof

musical insrrumentstu. The drum in CzekÀowski's dtawingis

quite differentftom

the Toro-Nyoro-Gandatype;

it

is

neater,but

not

completelysimilar'

to

theI(onzo-AÀba

type

indicatedby

l(laus

\il/achsmann'',and

onethat

we

sawduiing our

research. Moreover,the

Czekanowski drum is very similaito

the Banande type usedin

Congo 1,n the1980s.

In

genetal, we can say that theI{onzo

and Nande drums^re

both

more

"slim"

than

the

Ganda-Toro-Nyoro

ones'Furthermore, like Czekanowski's drawings, the Nande type has a very short cylindrical paft compared to the conical base and yet,

it

is

commonto

find

tlie

recentI(onzo

drumwith

a long cylinderon a

small base.As

such,the

contempof aryI{onzo

dnrm

is

avariation

of

czekanowski'sI(onzo

drumof

1908 and the Nande drum that Facci observedin

1986.The

l(onzo

drum

shares alot with

the Nandedrum

and a comparison would enhance out understandingof

this instrument'Althàugh

the

designand

shapeis

different

from that

of

the present-day,

we

àn

find

many

similaritiesin

terms

of

the p.rfor..ru.rée ptacticeand

rolesof

the

Banande and Bakonzoà*-r.

For

exìmple, three drums,in

both

cultures, are normally playedfor

dances.The

biggest has a roleof

a guide (enzoboli)'îrr.ia.

the drums there is a small stone, a symbolic obiect named "the testicleof

a wrzatd".It

is the symbolof

the drum's"hfe";

aî

aspect

also

sharedin

the Toro, Nyoro

and

Ganda

drum traditions.Continuity and Change in Bakonzo Music: From 1906 to

2006

229Facci notes how the drum

in

some occasions is symbolically linkedwith

the

m'(Ddmi (the clan chief.

A

special orchestraof

drums was

playedduring

the

enthronementof

a

new

chief. Engutaki and erigbomba are the names used by the Banandefor

the dance in this occasion. As one can note, Nande society, where the most important authorities Me the clan chiefs and there is noother

central strong pov/er, the engoma-pohacal relationship isless strong than

in

other culturesin

Uganda andin

genetalin

theGreat

Lakesregion,

particular\

in

the

Burundi

and

Rwanda kingdomsl8.Howevef, as

a

result

of

the

Rwenzururu Movement, the Bakonzo foundedtheir

own kingdom (although,until

now,it

isnot

officially recognized by the Ugandan government). Although the royal symbolsxe

engoma and the endara, during interviewswith

the musiciansin

2005, wedid

not

receive any information on the roleof

these instrumentsin

this new monarchy. Similady, noneof

them knew the Nande names erigbomba and engwaki, whereas other Nande dtual dances (for example, amasindwkafor

funeral, omukobofor

war,omukumu

for

maleinitiation)

were knownto

them.In

our

impression Bakonzo and Banande bothgive

relevance

to

anotheî symbolic

drum

meaning:

the relationshipwith

the ancestry.In

an interviewon

30 December 2005, Davis rù(/alina,a

drummer, saidthat

many people have adrum at home because

it

protects the house and the family from danger,and

it is

also

played

to

announcedeath.

He

alsoconfirmed what a number

of

Banande said about the roleof

the drumin

relationto

theevirimu,

the

spiritsof

the deceased. Assuch, the dtum, in this way, is a sign

of

family continuityle.Other

Musical

Instruments

In

another

photograph,

Vittorio

Sella

recorded

importantinformation

about the makondere orchestra, consistingof

side-blown gourd tnrmpets (see Figure 5)20.

230 Rwenzori: Histories and Cultures of an African Mountain

Figure

5

Vittorio Sella, "Native musical band at Unioro", 1906, Courtesy of the Sella Foundation.\Mhile

the

evidence availablein

the

caption accompanfngthis

photogtaph indicatesthat

theseate

trumpetsfrom

Toro,Roland

Oliver

has

reported

that the

Bakonzo

too

haveamakondere. However, Oliver attributes their origin

to

Buganda.He

allegesthat

some cians

of

the

Bakonzo

mtgratedfrom

Buganda andbrought

amakonderewith

them.He

writes

that, Rubongo, "broughtwith him

from Buganda the royal ttumpets-amakondere"t'.Ifi

fact, even today among the Batoro, as well as the Banyoro and Btganda, thisorchestr

ts a royal symbol.Howevet,

in

our

researchwe did

not find

any evidenceof

this kindof

ensemble among the Bakonzo. Nevertheless, another orchestra .wasvery

common: eluma,a

setof

twelveto

fifteen stopped flutes, each producinga

different

sound.Just

as the amakondereffumpets,

the eluma

flutes are

piayedwith

the ochetus technique,but the

functions are different.The

Eluma orchestrais

usedto

accompanythe

amasinduka fune:.al danceContinuity and Change in Bakonzo Music: From 1906 to

2006 23I

and

it

doesnot

seemto

be connectedto

any royal and political symbolism.\(/hile

Czekanowskidid not

mention eluma

in

hiswork, Klaus Wachsmann refers

to

this orchestra as belonging to the Bamba and the Bambutiin

Bundibugjo District. However, herefers

to

erumd,which

is

most likely

the

same aseluma,

and attributesit

to the Bakonzo, reporting thatit

is perfotmed "at the completion of mourningrites"".

Furthet,

while

all

the other

instruments documented by Czekanowski atestill

in

use, theteis no

longer^rry tî^ce

of

the pan flute todayor in

\X/achsmann's documentationof

the 1950s,even though pan flutes exist

in

Uganda among the Basoga,for

example. Someof

the instruments documentedby

Czekanowskithat

are stillin

use include: 1) the leg-bells esyonzendaworn

by male dancers; 2) the notchedfour-hole

flute enyamulere;3) the gourd îattles (the main instrumentfor

thekubandua,

a healing dtual and ancestral worship ceremony); 4) the horn engubl usedin

the pastfor

signalling and during the war dance omukobo; and5)

the

musicalbow

ekibulenge.The

ekibulengeis now

playedwith a

gourd

placed

on the

mouth.

Wachsmann

alsophotographed a man playing

the

musicalbow

in

this positiont3. However, Czekanowski did not mention^ny gourd. Accotding to him, the player put the bow between the teeth.

Czekanowski's

wotk

andthe

research doneby

Wachsmann documenta

musicalp^nor mà

similatto

the

onewe

observed during our research. Wachsmann's drawings, photos, and objects are conservedin

the

museum and, mostimportant

for

us, the musical recordings2a reveala

bigger numberof

instruments.In

addition

to

those mentionedby

Czekanowski, \ùTachsmann's list includes: 1) the hary enanga (or ekinanga);2)

the lamellophone elih,embe(or

erihembe);3) the

percussion bearn enzebe; and 4)the xylophone endara.

Another scholar, who went

to

the Rwenzori àteà^t the same

time

as

Wachsmann,was

Hugh

Ttacey,the

founder

of

theIntetnational

L1braryfor

African Music.

He

recorded

someI{onzo

music

in

1950.

lfe will

return

to

Tracey's

andWachsmann's tecordings later.

",ffif-232

Rwenzori: Histories and Cultures of an African MountainVocal Music:

A

Song Recordedin

L936Unforrunately, when Czekanowski arrived

in

Uganda, he did not have the phonograph he had usedin

Rwanda and so he did not record any music. The first audio recotdingin

the area was madeby a Belgian missionary M. Jules Celis,

in

Beni (Congo),with

aphonograph

of

the

Berliner PhonogramArchiv.

Celis was alsothe

fitst

to talk about the endara, the big xlilophone so importantfot

the

Nande-I{onzo

culture.He

recotdedonly two

Nande marriage songsbefore

the

machinebtoke.

Only

one

of

thesesongs

is vety

cìear.We

propose a transcriptionof

the

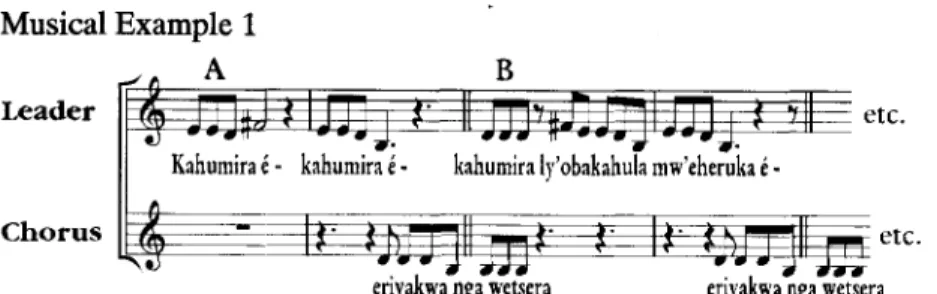

score in Musical Example 12s.Musical Example 1

Leader

kahumiraé- kahumiraly' mw'eherukr é

-Chorus

eriyakwa nga wetsera eriyakwa-nga-witlera

Nande wedding song, perfomed by women,1936. Extract.

(Solo.N{e1ody A) Kahumira, kabumira (Chorus Refrain) Eriyak zaa nga,{!)etsera

(A) Kahumira, kahumira

iWalking without knowing where (2t)]

lDptg

while asleep (refers to sex)] [V7alking without knowing where(2t)]@) Kahumira ly'obahabula

mu'eberwkare

[Valking

...

that's (A) Kahumira, kahumirabeing matried] fWalking without knowing where(2t)]

@) Kahumira ly'obakahula

mw'eherwkare

fùTalking...

rhat's being married]Conîinuity and Change in Bakonzo Music; From 1906 îo

200ó

233(A) Kahumira, kahumira [Walking

without

knowing where(2t)]@) Kahumira ly'obakahula

mw'eheruka.re

fWalking...

that's(A) Kabwmira, kahumira

being married]

f$Talking

without

knowing where(2t)]

@)

Kabumira

ly'obakahulamw'eberukd're

[S7alking...

that's being marriedl@) Kahwmira Baghenda w'abene babeghera [Walking

...

Those(A) Kahurnira, k ahumira

(Final)

Eriakwa

ngdluetserdly' obak ab ula mw' eh eru k are.

(A)Kabumira,

kahwmirawho move to other

peoplers houses must adaptl

ftValking without knowing where(2Ql

@) Kahumira ly'obakahula

mut'eherukdre

fWaìking...

that's being married][Valking without knowing whete (2t)l

lDl'irg

while asleepEriyakwa

that's being married.Dyingl

The song is clearl,v addressed

to

the bride. There ate explicit referencesto

the

new statusof

thev/onan

(bagbenda rD'dbene,those

who

moveto

other people's houses),who

must become amember

of

the

husband's fam1Iy26. Tine manrage (ly'obakabula mzu'eberukd.re,"th^t's

being married")is a

crucial moment; thegirl

doesnot

know her future ltfe

(kahumira,"rvilkins

without

knowing where"). For her this is like a death: her past lifein

the paternalfamily

is

"dying

while

asleep"(eriakwa

nga'@etsera).The term nga'(oetsera refers here

to

the sexual intercourse. \7hen someone entersa

new family,

thel' 1st-alhr

"-nt,

adaptto"

(babegbera) the nev' situation. This is what the song recommends to the bride: to die and to begin a totally new life in the husband's family.In

this sense the wedding is like an initiation ritualfor

the*oman'-.

et!

ò00S or ò0Q\ sro'i{'.:\zrsM ossor\sB ni sgnrrd) bss rgissri\rro3bns

ebnsnsfl

edr as boheq

3rnsz orIJgnirub

rizum drtudr

Ilirz zi

ztnemrrtleni Isnoiribsrr riedrìo

gninrrrsrll rud

,osno>ls8erlr

ni

.rsrlr -grilidieeoqedr

ebubxeew

nstr rcdtiz[A .trinoJaJneqosno)I-:bnsZ

ni

bsîeix:or

aegnsrìo

abnir{

rnersllib

<îzsq .e3r-roJr3qergiunitnoc

îo

eascs

:srgilsdumO riaumlo

noinslsz

s

b:,1slqsw

.è00Sni

>howbleiìtgo

gniruCl eredtOJ

:msz eriinO

.ansiciaum emoe or zOèQÌ:dr

ni bebro:srosno)I edl

.zezsc Jzomnloiaum

oroT bns ebnsZ

oels asw.osno)I-ebnsZ edr

rnorì

riaumoroT

:dl

berlziugnirzib ansirizumlo

enO .riaumosno)

erlrlo

elrir edr werul ozlsledr

zernitemo? etufì srs\nsnsrqss sdr no belslq Bnoz s ,sqs\sdsstrO asw z>lrsrl:dl

oaisbns

,ansiriaum edrilA

."1ersrT

1d

Oèalni

b:bro:er

bnsIlbz

ai

ri

bns ,eltit zti

bns

gnoaaidt

bssingorer ,elqoeq rerlro nsmredziì znsom s,qs\sdsstrO .rriuJnstr rzriì-,6tnewt erlrni

rsluqoq aid elidw .:>lsl edt ni bsib odw nsmredeil s tuods zi gnoz edr bns ,gorz edr.r:vswoH

.smod rs midrof

berisw abnsirl airl bnssliw

zirlt

lo

egnibrorer euoirsvbetosllor

e!7

.znoiergv auoirsv esdsrs\ssss,qss boog

A

.srs\smsqnssdt

no

be.lslq erewIIA

.gnozbns

aereiq Jrodeolni

lbolem edr

qu

a>lssrdlllsmton rslsiq

sbubni

1sm zirlt .zsrnilemoa ,bns anoilsirsvlnsm ni

li

zrnszerqew

lI

.vbolemnism

:dl

or

bsJslsrnu ,llerelqmor alitom Isriaum smoebniì ew

.a0èQledr

ni

bebrorsr

sqs\sùsssO:dt

es,llsns ew ,rslucilrsqnI

.eauni

llire els 3moe drirlwìo

.anre]]sq ribolemrnersllib

srIJIIs

ni

Înszerq medrlo

:no

esingo:er{iese

nsr .brsed ew srqs\sdssrOlo

anoiztev nsfo

noitqirrensrt erlt

Jnoz3lqsw

.S:lqmsxE

Is:iauM

nI

1d belslq

aslersrT

1d

bsbrorer ernsmroìreq

edrìo

tqrerx:

driw

berseqer ai nrslJsqribolem

rzriì

edT

.ensrbluMedmoiu8

Iebom eidT."4

met1s9" bemsn zi eno bnoreas

bns

znoiJsirsvneewJed aeron rlgid gnol 1d bssiretcsrsd] luoJnof,

rslurilmq

s asd .ntabngoer:wol

sdJnin\nuoM norì\N, nn\o zsruÌ\u) bns zsìrolzi\\ '.irostsw$. DtS

brsgsr

bluor

ew zeirfl edtìo

el6rz erlr bns gninsem sdrrof

aA(zgnoz gnibbew ebnsZ

ìo

eriotreqer egrsl erlrìo ilsq

zs gnoz aidraidr

nI

.a08Ql:rlr

gnirvb beeu oals <nemow 1d bsmroìreq zlswlso\À/ aJf,sqes Isriaum

tnsnoqmi

edrlo

vnam evsd oals 3v/ Bnoz .drrseaer ruo gnirub betonelgta nommof, 1tsv s

ni

zi eznoqaer bns IIsrlo

mrol

edt ,tarill-sbnsns8 edt

1d

beau .qlevianeîxebns

etuJluf,"uîrìsf["

sdJlo

srll

rof

emiJs

bns

taiolozerlt

rol

smij

s

ai etsdT

.osno>ls8 eegnsdr driw srnir rerl\zirl ssinsgto1l:srl

nsr Jaioloa edT :arnod: s sdil ,noiair:rq driwni

asrnor nisrìer sdr rud .anoilssivorqmi bns .rgJsmonorrl: cidqorrzs

svsd

Ìon ob

o\M (Jt.sq e'Jaioloaedr

ni

.bnoce?ni

bebiviblbolsm

s Jud .rieurn nseqoruEni ngtlo

:/il

.srut:urtz,1ns

ni

zllsq

o\À/-J eaedt gniensr

jziolozsrlT

.B bnsA

raltsq ow-J edt .szsr airlrnI

.anoilsirsv bns anobitsqsrìo

zbnbl IIs dtiw .rebro rserlnsr

e\À/ (revooloM.A

BA

g fl

A g

A

BA

B

A

A

:zimrol

3lom

driw

rud

(ooJ riaum

Istnemur]zni

srlr

ni

mrof

zirlt .znoiîsirsv bns znoilsJnomgeu berscireidqoalhseb îon

eiri

fi

neve tsedrslug:r

s

end gnoz edr .brirlT rsed sdrfo

smil

edT .(gniqqslc-bnsddtiw

ecnstzniroì)

beazerqxeni

nommor,nev

IIba ozls eidridw,(---

--- ---) zrelqirr ni bebivib ai .riaumosno)

TruJnof, raril-r6tn:wr edrs

gniraeggue.(ruoì

{no)

weì srs

bszrr ze}on edJ .dtruoT bnslersrT

rlguHlo

gnibroret sdl ni .revewoH .m3Jeyz rinotsrtsJs ni bemroh3q nefio asw rizum

osno)I

,a0èQl edt ninnsrnedrslf

ni) rrrns8 odt gnoms noilqecxe ns sd bfuowtI

.merzle oinotstqerlai metzle Jnsnimoberq sdr

eredw,(sbnswf

bns .ibnuru8 .sbnsgUrof

agnoasbnsVI smoz ,z08Ql

edr

ni

.rsvewoH

.rinotstneq (z3Jofilo

:gnsr

eviansix:

ns bsrl

(nemow1d

gnua .egsinsm:dr

e>Iil ,bnuorg>bsdedr

ni

msta,qz:inotsrneq

s

ìo

svitzegguansr e!7

Snsem aidr aeobrsd!7

.òeQlni

bebrocer gnoa osno)Iedr erofed nommof,

zaw msJeye:inorstneq

srb tsdr

ozoqqrrzedt

lo

gninrt

erlr rsrlr bns

osno>ls8edr

lo

noirnsinsirairdf ,tevswoH.r:tsl

mslala rinorstqsd s oîr:eob

emsr:d

zln3mut]ani .noianemib Isurir rierbroì

tnsnoqmi .egnoz gnibbew slsmeì emoersdto

:noilizoqque s{no

ai zidr ru€l .elpa"l3blo"

nsni

beJeizeroJ bns

noirssinsitairrl)

or

betceiduzerew sbnsgU

ni

elqoeq236 Hísîories and Cultures of an African Mountain Musical Example 2 Drums (inner rhythmic pattern)

B-B_

B_

Pattern AOmubaliya, perfomer Bukombe Mgkirane, 1950. Extract.

Tl-re meiodic contour

of

NlodelA

in all the performancesof

Omubaliya is easilr, recognizable as we can see in Nlusicalr al{)

Example J

Musical Example 3

@F

Bagheni's version, 2005A

last extract comesfrom

a recording done by Serena. Facctwith

I{ambalel{imavi,

a Nande musicianin North

I(il'u".

The nameof

the song isEkibaliya

(the bad fisherman), and the song tellsthe

storyof

^

màrrwho

diedin

the

lakewhile

his

friendwaited

for

him. The

melodyis

alittle

distantftom

the l(onzo

grolrpof

melodies, andit

was impossibleto

fìnd

the Pattern A.B_

Kule's version, 1954

Erisania's veision, 2006

Desesi's version, 2006

Contirutity and Change in Bakonzo Music: From 1906 to

2006

237But

some similarity could be foundwith

another pattern.If

we look at Musicallìxcetpt

4, there is a melodic cellule chancteúzing the repeated melody, indicatedwith

"B". It

is a simple descendingsequence

of

sounds (with inten'al of a second and a final third). Musical Example 4B_

B_

B_

B_

Ekibaliya, perfomer Kambale Kimavi (munande), 1986. Extract.

This

celluleis

also

repeatedin

somel{onzo

versionsof

Omubalia.

See the cellule B in Musical Example 2.Continuities

and ChangesinEndara Xylophone

Although

it

is

an

important

instrument amongthe

Bakonzo, (,zekanowskidid

not mention the endara xylctphonein

his 1908clocumentation. However,

in

the 1930s, Humphreys, an explorer climbingthe

Rwenzori, sawthis

instrumentin

the

centreof

a ,'illager2. Gerhardl(ubik,

who came near Bwerain

1962,but onlyfor

a very short

time, recorded the endara anclwrote a

paper comparing thel{onzo

and Ganda xylophones. However, detailsof

his

findings are outsidethe

scopeof

the

present discussion.The

endara, played together

with

the

drums,

has

been

animpottant magico-religious instrument among the Bakonzo;

it

isnot

an

instrumentthat is

ownedby

anyone.The

endara hasalv'a1s been associated

with

Kitasamba, the headof

the Rwenzori spirits, the godof

the Bakonzo.In

fact, Gerhardl{ubik

reportedthat

"\)7e soon

observedhow much the

Bakonjo

fBakonzo] music is connectedwith

Bakonio religion; this holds truefor

the xvlophone music"33. Further, narrating his experience during anexpedition

to

the Rrvenzori Mountainsin

1974, Bernard Clechet flX4eiteFather) reported

that

although

they

con','erted

to238

Rwenzori: Histories and Cultures of an African MounîainChristianity, the Bakonzo still

bult

KitasarnbA"z

small shrine inthe

form

of

a

xylophone"34. Similady,during

our

tesearch in 2005/2006, we attended the new-year's eve ceremony at Kihaasa village,where the

endara featured asa

prominent

instrumentduring

the kubandwa thanksgiving ceremony. Florina Mbambu Nvamutooto, about 46 yearc and fotmedy a Roman CathoJic (sheactually had a rosary), u/as the mbandzua, the priest.

\flhile

there

wete

definitely

someevident

changesin

the structureof

the instrument compared to what Klaus tùTachsmann describedin

1.9533s, there arestill

some continuities. Similar to what Wachsmann noted, the endara which was petformed duringthe kubandl!)A ceremony, had sixteen slabs and was also mounted on banana stem supported

by

short srumps. However, the slabswhere separated

from

eachother

by

reeds insteadof

sticks asrepoted

by

Wachsmann.Unlike

'Wachsmann'sreport,

weobserved

four

performers insteadof

five

playing the endara tnintedocking

style. Further,we

weregiven different

namesfot

someof

the musicalpats in

comparisonto

what

Wachsmann'was given; and these include:

According to Wachsmann,

A

isomukirinya

and mugus'(!)e oromubumbiriri,

while

we

were

told

that

it is

ebikekulu. Wachmann reportedB

asontultimbiriri,

while we weretold

thatit

was obanana. -ù7e weretold

that partC

was enzoboli and ttrisonly

differed

from that

of

Wachsmannin

spelling;it

was1ffiffi

Continuiryn and Change in Bakonzo Music: From 1906 to

2006

239"nzbobolye". 'SVe

were informed

that part

D

was ebidenguli, while Wachsmann reported them as omusakulwe. From this data,it

is impossibleto

establish whether there has been a change inthe

naming

of

these

parts

or

whether

the

differences^re

accounted

for by

the

difference

in

infotmants

and

their knowledgeof

the endara.However, comparing research

on

the endaraof

the Nande,who

are closely relatedto

the Bakonzo, might give us a clue tothe

wayin

which

there has beencontinuity

and changein

the Konzoendara.In

her studyof

the Nande, Facci reports that the endara has fifteento

seventeen keys, which iswithin

the rangeof

what \X/achsmann and

we

observed3T. \W4rile Facci concurs with Wachsmannon

the five-player system, she differsin

the namingof

the parts playedon

the

endara. However, Facci's naming iscloser

to

the one we were given during the 2005/2006 tesearch;obwana

and "enzoúoli"

&ot

the

more correct

spelling

isenzoboll

refer to the same endara parts.In

her

recent

researchon

I(onzo

endara, Yanna

Crupicompares

many

diffetent

instruments

and

groups

of

performers". Her study reveals that the numbet

of

four players isnow

common. However,other

features such asthe

numberof

the logs or the nameof

the musical paîts are various. Crupi's dataconcurs

with

Wachsmann's andwith

other studiesin

the useof

the

termsenzoboli

andomwana

(or

obanna). Tine enzoboli isthe name of the main musicalpart and omuana is the part played

on

the

smallest high-pitched logs. Omwanais

thel(onzo

wordfor

child (obuana means childhood). As we said above, this termis

also common amongthe

Banande: they useit

for

the

high-pitched keys of the xylophones and other instruments.\Mhat

still

holds

with

Wachsmann's researchis

that

theBakonzo endara

is a

rzre

instrument,

and

besides being performedin

chutches and during school festivals, outside these240

Rwenzori: Hi.yÍories antl Cultures of an African Mountctinl{owever,

the endara takeson

nev/ designsto

fit

in

the

schooland

church

contexts, anclthe

meaningof

the

music

is

alsoreconstructed.

For

instance,due

to

their poor

durability,

the banana stems are replaced with wood boxes as the fiamesfor

theendara. Probably

the

redefinition

'f

the

endara performancecontext

could help

to

explainits

rariq..

Becausethe

endara performancewe

observed wasin

a ritual

cofltext,it

had other props aroundit,

and these included a basket in r,,,hichmonel

andherbs rvere

put.

()n

either sidesof

the endara werea

sorghum stalk, a corv's skin, andtwo

flowersof

a reed plant. There wasconstant sprinkling and drinking of local beer made from bananas

and

sorghum, asv-ell

as continuous smokingof

tobacco and marijuana by the mbandraa and the musicians.In

1966-67, Peter Cooke recordedl{onzo

endara music inmany

villagesin

Bundibudjo,

I{aseseand

Brvera Districts3e.cooke

arri'ed

during a crucial time during therebe[ion

againstthe

Batoro

by the

Bakonzo

Rwenzururu Movement.He

alsorecorcled many

protest

songs. Someof

them

arestill

sun(g as accompanimentto

dances. However, these songs hacl multiple meaningsand cannot

be

taken

literalh,.

Besjdespr.r..rt-g

protest, some

of

these songs emphasized tlìe stronglink

between the Rwenzori and the peopleof

the mountain:,,If

a rù(/hite comefrom

the mountainfollow

him,if

a white comesfrom

the \ùíest, don't gowith

him"a". The"White

comingfrom

the mountain" isthe snow, the symbol

of

I{itasamba, the white godof

the snowy peaks.During the

Rwenzururu mol-ement,white

became thesymbolic

colour

of

the

prorest.

The

whites coming

from "elsewhere" are the Basunppr: the Europeatrs. Thev also referredto

the Batoro becauseof

their close connectionwith

the Rritish aspart

of

theBrìtish

dir.ide-and-rule policv. Further,in

a joint

publication,

Cooke and

Martin

Doornbosai reveal

that

the enyamulere wasvery

commonat

beer parties andthe

melody always camefrom a

song.The

flute

was accompanied b). the percussion beam enzebeor

bv

a

drum

beatingthe

commonConîínuiftt and Change ín Bakonzo Music: From 1906 îo

2006

241 pattern of triplets. Thev also transcribed a new corpusof

songs in European style.Comparing Nande

andKonzo Music,

The

political instabilin-of

the late 1960sthat

culminatedin

Idi

Amin's

overthrow

of

the

govetnment

in

1,971,had

asconsequence the deportation

of

all foreignersin

1972. As a re sult, researchon

Bakonzo music, like any other music, was curtailecl.Facci's study

of

the

llanande later,in

1986-1988,is

the

onll' available research that can help us trace the musical developmentof

the Bakonzoin

thel^tter

partof

the

twentieth century, andthese findings are useful

to

compareto

olrr

joint

studyin

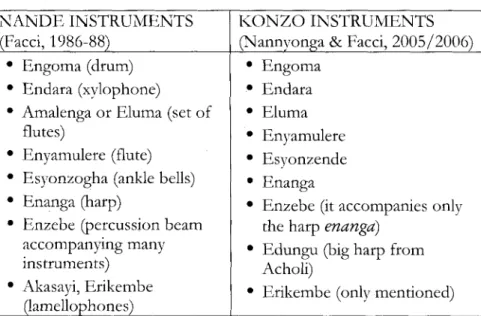

2005-2006.In

Table 3, l-".e compare the Banande musicin

the 1980s andthe Bakonzo music we documentecl

in

2005/2006. The important musical ensemble (engoma, endara, eluma)is

at thetop of

the list.The

solo instrumentsfollow.

Some secret ritual instruments@muhumu) arc at the end.

Table

3

Nande and Konzo MusicNANDE,

INSTRUME,NTS(Facci, 1986-88)

KONZO

INSTRUME,NTSQ.iann1,s1ga

&

Facci, 2005/2006)lingoma (drum) Endara (xvlophone)

Amalenga or Eluma (set

of

flutes)

Enyamulete (flute) Esyonzogha (ankle bells)

Enanga (h^tp)

Enzebe (percussion beam

accompanying many instruments) Akasayi, Erikembe llamellophones) Engoma Endara Eluma En1'amulere E,syonzende Enanga

Enzebe (it accompanies only tlre harp enanga)

Edungu (big harp from Acholi)

Erikembe (only mgnlioned)

'

Akaghoboghobo (fiddle)'

Endeku (one-hole flute).

f\nzenze (zither)'

Ekibulenge (musical bow)'

()mukumu (setof

percussion beams for the male initiati on olusurnba,

it

'was a secret instrument)'

Endingiti (fiddle, only mentioned)t

Enzenze'

Ekibulenge'

Omukumu (now used by cultural groups)'

Gourd rattles and bellsfor

hubandrua242 Rwenzori: Histories and Cultures of an African Mountain

Comparing

the

ensemblethe

instruments

used(engoma, endara, eluma, enzende-enzogbQ are the same

in

both Bakonzo and Nande culrures.The

engoma and the endara arethe

most important

instruments

during

weddings,

funerals, political meetings, traditional rituals and competitions. However,there

^re

some

differences:

for

the

Banande

the

endaraaccompanied dances.

This

dance, also named endaralike

the instrument,is

neither a genderednor

an age-specific dance; anyperson irrespective

of

genderor

^ge could dance

it.

Further, the endara has a very important place duringthe

traditional riruals, especiallykubandwa

amongthe

Bakonzo, àswe

saw before. Dudng the ceremony the spirits are invokedwith

ratdes and belisaccompanied

by

the engoma inside ahut, though

the endara isoften

played outsidea2. However,in

the

1980s the Banande didnot

practise

the bubandzaa (at leastin

the

open, accessible to 'Westernscholars and missionaries) as much. Was the endara a

teligious instrument

for

the

Banandebefore

Christianization, when they were devotedto

the ancestral spirits?If

so, is the lossof

the endara in ritual functions one of the signs of the erasureof

the traditional religion?

Or,

did the traditional priests embandua perform the dtualsin

secret,without

the endara (a big instrument producing loud sounds)?Continuity and Change in Bakonzo Music: From 1906 to

2006

243The

Banande and Bakonzo musicalttaditions

differ

morewith

regardto

solo instruments including harps and flutes. For example,the

litde

one-hole flute

ndehu, usedby

the

Banande (mosdyby

children)is

completelyunknown

by the

Bakonzo.lVloreover,

akasayi,

a

Nande plugged insttument

with

ahemispheric

gourd

resonator,

is not

famihar

among

theBakonzoa3.

In

some cases, the instruments are similat, but their function and relevance is different.In

the 1980s, rhe enanga and erikembehad

afl

important

function

for

the

Banande.Both

theseinstruments (common

in

many

Ugandan cultures)were

usedduring the evening, at home

or

in

the buvettes, and on the local radio. The plavers sang theold

songs usedfor

dancing, as well as some epic songs,but

the biggest sourcefor

their new repertoire was topical issuesor

sometimes personal life expetiences. Among the Bakonzoof

the 21st century, the erikembe and the enanga isless

in

usein

general ceremonies. The enanga is mostly usedin

the church, accompanying Christian hymns. The strings (eightin

the pastaa) are now nineot

elevenin

number, and the tuning is inthe

temperate system.This

instrumentis

changing becauseof

influencefrom

other Ugandan culfures. For example, we saw the enanga playedwith

the adungu, the big harpfrom

the Acholi, innorthern

Uganda.

Ate

these

transformations

a

sign

of

"modernity"

or was the enangd less importànt to the Bakonzo inthe

past

too?

Is

that

the

reasonwhy

Czekanowskidid

not mention the enangain

his reseatch onI(onzo

music?In

fact, in Wachsmann's recordingsof

the

1950s,the

songs are short and repeated many timesot. Similady, Erisa Muhonja, sonof

a

late enanga playerin

Ibanda, told usin

an interviev/ that he could not recallhis

father's repettoire.It

is

also interestingto

rememberthat

Wachsmann,in

his

noteson

bow-harpsin

Uganda, talksabout the "disappe r^nce

[of

the harp]from

musicallife of

theGanda"a6.

Aftet

independencein

1.962, the hatp became oneof

the instruments usedfor

musical educationin

school,but

rarelyfffiffi-244

Rwenzori: Histories and Cultures oJ an African Mountainexists

in

the 21st century. Maybe the historyof

theI{onzo

harp hasto

be

seenin

a larger contextof

the

evolutionof

this very ancient instrument in Uganda.TL.e enyamulere

(flute),

documentedby all

the

scholarsduring the past century among the Bakonzo, is also very populat today. Flowevet,

it

wasnot the

samefor

the

Banandein

the 1980s.The flute

players were less respectedthan

the

end.ngaperfotmersot.

The Banande and Bakonzo also use the enzebe, a percussion beam,

in

a different v/ay. This object was a sortof

obsessionfot

the Banande.

The

enzebe,with

rhythmic patterns, accompanied .each solo instrument,

for

instance the harp,flute

and zither.In

Bwera District, we saw the enzebe played only once with enanga.However,

in

1953,I(laus

\X/achsmann recordedthe

percussion beam playedwith

endngd.On

the other

hancl,Peter

Cooke reported the enzebe playing wtth enyamulere,butin

alot of

hisrecordings

this

flute was accompaniedby the drum

andnot

by enzebe.In

some cases, the enzebeof

the

Banande (maybe alsoamong the Bakonzo) was used as a substitute

for

the drum. The reason mav be because the enzebe is a cheap instrument;it

can befou.nd everyvhereot, wheteas

the dtums

needto

be

madeby

a specialistwith

particularwood

comingfrom

the

forest and theskin

of

a

cow,or

a

leopard. However, some aesthetic reasonscould

be

noted:

the

high-pitched

soundsof

the

enzebe^îe sometimes preferred

(in

the

caseof

the enanga.for

example).The

l(onzo

drummers sometimes playon

the wooden edgeof

the instrument

to

createthe

effectof

the

enzebe.This kind

of

beating is named esyongakatero.The

musical featuresincluding tuning, melodic

contours,imptovisation

and vatiation, and rhythmic

organtzation aîesomehow similar.

A

deeper study mustto

be doneto

compare the various repertoires. One key musical concept which must bementioned

is

the

concept

of

e-enzoboli.

It is a

sound, correspondingwith

one

specifìc stringon

the

harp,log

in

theNANDtr,

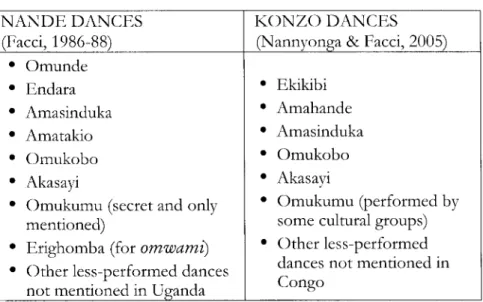

DANCtr,S (Facci, 1986-88)KONZO

DANCtr,S (Nannyonga&

Facci, 2005)Omunde Endara Amasinduka Amatakio Omukobo Akasaf

i

()mukumu (secret and only mentioned)

Erighomba (for omzuaml Other less-performed dances

not mentioned in Uganda

Ekikibi

Amahande Amasinduka Omukobo Akasavi Omukumu (petformed by some cultural groups) ()ther less-performeddances not mentioned in Congo

Conîinuîty and Change in Bafuinzo Music: From 1906 îo

2006

245 xylophone,or

flutein

the eluma flute set.It

has a particular rolein

the

music,which

thc I{onzo

musicians seemto

be

morc explicitin

defìning than the Nande playerso'.For

the Bakonzo, the enzoboli "leads".It

is

the most importantpitch

or

the most important partin

an ensemble.In

the xylophone oneof

the four(or five)

parts hasthis

nametoo:

it

is

the part

chargedwith

reproducing the main tune in the group.While we do

not

dealwith

any dancein

this paper,it

would be important at least to include a listof

dances as a suggestionfor

^î

aÍea that needs future explotation. As such, Table 4 shows, asa comparison, the Nande dances as observed

by

Facci between 1986-1988 andthe

I(onzo

dances as observedin

2005/20O6st'.The dances are in orcler of relevance :

Table

4

The Nande and Konzo dances\ù7e can note that some dances are common to both Banande

and

Bakonzo.

For

example,

some

ritual

dances:

1)

the amasinduka, performed during funerals;2)

the omukobo, an old war dance in which two dancers do the pantomime of a fight; and246

Rwenzori: Hisîories and Cultures of an African Mountainolusumba.

However,

the

most

often

performed

dances,documented during

the

two

researches, are different.The

most popular dancefor

the Banandein

the 1980s was the endara, the dance around the xy'ophone. The Bakonzotn

2006did not

usethe term endara

to

denote a dance. $7ith the accompanimentof

the endara, they performed other important dances and mosdythe

ekihibi,

a

mixed

dance

Gk"

the

Nande endara)

alsodocumènted

by

Peter Cooke

in

1,966.The

munde,

another famous perfotmance amongthe

Banande,is

an

athletic maledance, completely unknown

to

the Bakonzo. The wedding dancedTndtakio (for young

gid$

is also specific to the Banande.Facci's tesearch

of

the

1980s revealedthat the

Banande musical customs u/ere very clear about the different performance rolesof

men and women. 'W'omen,for

instance, didnot

play anyinstruments.

Further,

many danceswere

specificallyfor

eithetmen

or

women.

It

was only

the

endara

dancewhich

wasperformed

by both

genders. However,motifs

for

male dancerswere

more

complexand

acrobaticthan

those

of

the

female.During

an

interview, some

informants

told

Facci

that

the Christian missionaries had influenced the style of performing, andthe more

erotic mixed

danceswere

disappearing.Of

coutse, deeper explorationof

the truthof

this statement is needed before one can objectively confirm it.In

our tesearch in2005/2006, we verified on many occasionsthat Bakonzo women do not play instruments. However, looking at the dance tradition,

we

always saw men and women dancing together.In

the ekikibi, the most

popular

dance,men

andwomen perform different

but very

explicit erotic

movemeflts.This

danceis

performed

during the

weddingsand

has beeninterpreted

as

a

courtship

dancest.

M"È.

the

Christian missionaries had less influenceon

thel(onzo

dancers than theyhad over the

Banande,or

possibly theremay

be

some otherreasons that would now be too

difficult

for us to investigate.Continuity and Change in Bakonzo Music: From 1906 to

2006

247Reinvention of Konzo Music

f'he

establishmentof

cultural groups

and the promotion of

indigenous music education

in

schools and school festivals by the UgandanMinistry

of

Education has contributed alot to

the

re-invention

of

not oniy Konzo

music,but

alsoof

other

music culturesin

Uganda52.Th"

1960swere

a

period when

cultural groupswete

beginningto

developin

manyparts

of

Uganda,inspired

pardy

by

the

troupe

"Heartbeat

of

Africa"

(which performed at Uganda's National Theatre and at state functionsin

I(ampala as well as overseas) and pardy by the growth in teachingof

traditional music

in

schoolsand

colleges. These "culrural groups" were establishedwith

the aim to preserve local traditions tlrrough performance.In

October

1967 Peter Cookefound

anactive group

from

Bwera caliing itself the "Rwenzori Drama andCultural

Society"performing

in

public

for

the

Independence Annivetsary celebrations at I{asese. The group had been fotmedtwo

years previously.Cultutal

groups arenow

found

in

many Bakonzo villages. They perform at public gatherings like politicalrallies, wedding ceremonies and competitions orgarized at village,

county

and

district

levels.

The

musiciansare often

semi-professional and, likein

many other partsof

the wodd, prefet themore

spectzcular repertoires,like the

dancewith

the

endara xylophone otwith

rhe eluma setof

stopped flutes.The formation

of

the

cultural gtoups and

promotion of

school music and dance festivals has had some influences too.

For

example, near lbanda,a

local

culruralgroup

performed a dance similarto

that

which

Facci and Cecilia Pennacini filmed near Butemboin

1988.This

dance was originally perfotmedfor

the ptesentationof

a newbornto

the

sun. The womanwho

led the dance did a pantomime showing howto

carry the baby usinga

monkey skin.Near Butembo the

dance was performedby

a groupof

traditional obstetricians.At

that time, manybirth

ritualswere

disappearing,mostly

becausemany

mothers

went

to hospitalsto

give

birth.

These 'womenv/ere howevet able

toperform

the old

dancesand

rememberedthe

ritual very

well,248

Rwenzori; Hisfories and Culfures of an African Mountainprobably because they had performed

it

oftenin

the pasr.All

thebirth

rituals, they said, were strictly for women.However,

when

the l{onzo

Ribuni Cultural Group

in Nvakalengija proposed the same dancein

2006, noneof

the girls present wantedto

interptet the protagonist: the women dressing and movingin

the monkey skin.It

was an informal situation, wearrived

without any

announcementand the group was

not complete. The main clancer and group leader*u,

o boy.He

did not mind dancingwith

the skin, like a woman.Of

course the new context (it was not a ritual, but its enacrmenr) permits this changeof

role. Maybein

the futureit

would benormal

for aI{onzo

or Nande woman to play the engoma or the enddrd.In

conclusion,we

cafi say

that while

there has

been substantial continuity, there have also been a numberof

changesin

the music and danceof

the Bakonzo, dueto

changesin

thepolitical, social

and

cultural

environment.

\)7e

have

alsodemonstrated

that

dueto

the close connectionof

the Bakonzoand

Banande,the

history

of

the

Bakonzo music canonlv

be accessed through an understandingof

the Banande. Finally, the gapsin

this

paper

will

hopefully

stimulatefurther

exrensiveresearch

on the

Bakonzo,

a

musically

rich, yet

largely uniesearched culture.Notes

1.

This paper is a collaborative effort based on data collected j.intry in December 2005 and January 200ó, as well as prior research <ione bySerena Facci since 1988, on the Banande music.

2.

The oral sources are interviews conducted in December 2005 - January 2006. The musicians interviewed includecl: Manksi Bagheni (Mihunga*

Kasese District),I{yiti

Erisania,I{ule

l{osimu, Baluku Bwenge (ì.J),amurongo- Ifondo

Sub-county), Baluku Desesi Q\yakalengija-I{asese); I{ule Mbakwa (Mihunga

-

Kasese), Erisa Muhonja (Ibanda-I(asese), Mbasa Marani, Milton I{ule (I{inyabisiki, I(1,ondo), Nzwcnge

Gidion (IQbuyiri

-

I(asese), Thembo l{umasa Q.Jyamurongo-

I(yon,1.,;, Isembwa Sele Q\yakalengija-

I(asese), Kisamba Cultural (ìroup, 'Zed,ekya4.

5.

6.

Continuity and Change in Bakonzo Music; From 1906 îo

2006

249Moiyugha (I{isamba

-

I{asese), Rubuni Cultural Group, Davis $falina Q\yakalengija-

I{asese). \rVe appreciate the work by Stanley Baluku ancl Hilary Baluku I{ikumbwa, who were our interpreters. As far as documents are concerned, duting the 1950s some ethnomusicologists began to workin

the area. Hugh Tracey (1'950, 1952) and l(laus Síachsmann (1950, 1953) coilected some music for two ìmportant Afrìcan institutions: the International Library for African N{usic and the I(ampala Nfuscum. Tracey also went to Congo and recordecl the Banancle music. In the 1960s, after the independence and the aclvent of the national republics of Congo and Uganda, two other schoiars arrir.ed in the atea, both studying othet areasof Ugandan traditional music: (ìerhard l(ubik and Peter Cooke.

()n his expedition t<> reach the highest peaks, see Pennacini, C. (ed.) 200(r.

I popoli della luna - Tbe People of tbe Moon. Ruenzori 1906-2006, Cahier

M useomontagna, Torino.

As quoted in Moisala, P. 1991. Cwhural Cognition in Mwsic; Continuity and Change in the Gurung Music of Nepal, Gummereus, Jrvàskylà, 13.

()livet, R. 1954. "The tsaganda and Bakonjo [Bakonzo]".In Uganda lournal,18, 1,31-33.

Nzita, R. & Nfbaga, N. 1993. Peoples and Cuhures of Uganda,l"ountain Publishers, I{ampala, p. 39.

Mushauri, K. T. 1981. "()tganisation étatique des Vra, et son origine". In

AA.VV , La civiLization ancienne des peoples des Grands Lacs,I{arthala, Paris,160-169.

See also Baluku, R. 1999. Marriage Customs antong tbe Bakonzo in

Uganda,BA (t,uw) Dissertation, Makerere University, 1.

Trowell,

M.

1953. "Domestic and Cultural".In

N{. Trowel&

I(. \íachsmann, Tribal Craft of Uganda, Oxford University Press, Lonclon, iì.Pennacini, C. 2006. "On the Slopes of the Rwenzori. Ethnology of an African l"rcrntier". In Pennacini, C. (ecl.), 2006, p. 21'5.

On the I{onzo rebellion against the Batoro cluting the twentieth century and on the Rr.venzururu movement, see Alnaes, K. 1969. "Songs of the Rwenzururu Rebellion. The I(onzo Revolt against the Toro in \festern

Uganda". In P.H. Gulliver (ed.) Tradition and Transition in East Africa,

Routiedge & I(egan Paul, London,243-272; Stacey, T.2003. Tribe' Tbe

Hidden History of the Mountain of tbe Moon, Stacey lnternational, London; Pennacini, C. 2006. 3. 1. 9. 11.. 10.