UNIVERSITÀ POLITECNICA DELLE MARCHE

Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences (D3A) PhD in Agriculture, Food and Environmental Sciences - XV (15° edition)

AGR/01 - Agricultural Economics and Rural Appraisal

THE SHORT FOOD SUPPLY CHAINS’ PHENOMENON: A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO EXPLORE

CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR AND PREFERENCES

DOCTORAL THESIS

PhD Candidate: Supervisor:

Elisa Giampietri Prof. Adele Finco

Co-Supervisors: Prof. Fabio Verneau

Prof. Teresa Del Giudice

2

“And later on, when so many roads open up before you and you don't know which to take, don't pick one at random; sit down and wait. Breathe deeply, trustingly, the way you breathed on the day when you came

into the world, don't let anything distract you, wait and wait some more. Stay still, be quiet, and listen to your heart. Then, when it speaks, get up and go where it takes you.”

“E quando poi davanti a te si apriranno tante strade e non saprai quale prendere, non imboccarne una a caso, ma siediti e aspetta. Respira con la profondità fiduciosa con cui hai respirato il giorno in cui sei

venuta al mondo, senza farti distrarre da nulla, aspetta e aspetta ancora. Stai ferma, in silenzio, e ascolta il tuo cuore. Quando poi ti parla, alzati e và dove lui ti porta. ”

4

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION………...6

CHAPTER 1: EXPLORING CONSUMERS’ ATTITUDE TOWARDS PURCHASING IN SHORT FOOD SUPPLY CHAINS………...………...34

CHAPTER 2: COMPARING ITALIAN AND BRAZILIAN

CONSUMERS’ ATTITUDES TOWARDS SHORT FOOD SUPPLY CHAINS………...………...54

CHAPTER 3: EXPLORING CONSUMERS’ BEHAVIOUR

TOWARDS SHORT FOOD SUPPLY

CHAINS………..74

CHAPTER 4: TELLING THE TRUST ABOUT CONSUMER

BEHAVIOUR: A THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR PERSPECTIVE TO INVESTIGATE FACTORS INFLUENCING CONSUMER PURCHASE AT SHORT FOOD SUPPLY CHAINS………..………..106

5

CHAPTER 5: CONSUMERS’ SENSE OF FARMERS’ MARKETS:

TASTING SUSTAINABILITY OR JUST PURCHASING FOOD? ………...131

CHAPTER 6: HETEROGENEITY IN CONSUMERS’ PREFERENCES FOR FARMERS’ MARKETS: A COMPARATIVE

ANALYSIS AMONG ITALIAN AND GERMAN

CONSUMERS………..170

6

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, decreased consumer confidence in industrialized agri-food systems and enhanced reflexivity of consumers known as “quality turn” have led to the promotion of Alternative Agri-Food Networks (AAFNs) as Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs). The worldwide flourishing development of SFSCs has motivated a renewed interest for researchers all around the world. However, the majority of such studies, that aimed at processing knowledge in such marketing systems, faced some problems: the wide variety of forms and the difficult access to data hampered an exhaustive and comprehensive assessment of the impacts of SFSCs.

As abovementioned, during the last decades, agriculture and agri-food sector faced some significant changes (Toler et al., 2009). The

industrialization and globalization phenomena, in particular, are

mentioned as major reasons of modern food systems’ recognized

unsustainability.

First of all, Mundler and Rumpus (2012) state that in response to pursuing high-production volumes, high-standardization levels and low-food prices, intensive agriculture and industrial food production exact heavy environmental costs, due especially to their strong dependence from fossil energy and massive food wastage. In addition, Reisch et al. (2013) suggest that climate change, water’s pollution, scarcity and eutrophication, soil degra-dation, and loss of biodiversity

7

represent only some major environmental problems related to modern food systems.

It is worth noting that farmers’ economic unsustainability, especially for small farmers, represents another problem linked to conventional longer and standardized food supply chains. Small producers, indeed, commonly suffer from a little bargaining power and are often excluded by globalised systems because of their limited resources and difficulties to combine production, processing and marketing skills. Imposing the existence of many intermediary actors within the supply chain, the mainstream large-scale food systems also drastically undermined farmers’ profitability over the last years. In addition, as stated by Assefa et al. (2013), “the last decade, and particularly since the 2007/08 food crisis, food price volatility in world markets has seen an increasing trend. The successive reforms of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which made EU agriculture more market oriented, led to the exposure of EU farmers and consumers to world price uncertainties”. In particular, increased market competition and price volatility contributed to significant income losses for small producers, who started to search for alternative profitable solutions. According to Tangermann (2011), volatility is a characteristic feature of agricultural markets and there are all reasons to expect that it will continue to plague them in the future.

8

Finally, with regard to social aspects of food production and provision, among other academics Thorsøe and Kjeldsen (2016) denounced a notable social, physical and temporal distance between

farmers and consumers throughout the last two decades. In 2013, the

European Commission (EU, 2013) declared that, in addition to concerns related to food crises and environmental pollution, to the increasing ethical awareness of social responsibility and of the rising prevalence of malnutrition, and the influence of foods on wellbeing (e.g., diet- and lifestyle-related health problems as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases that significantly increase health costs) have shaken a large proportion of consumers’ confidence. In parallel with this, food scandals and scares (e.g. BSE scandal, avian flu, horsemeat scandal) (Forbes et al., 2009) contributed to increase the information asymmetry and consumer distrust and generated new anxieties about food (Thomas and Mcintosh, 2013).

According to Meyer et al. (2012), the decreasing of consumer proximity to food production and the increasing gap between producers and consumers contribute to the erosion of consumer

trust, that grows when the risk of moral hazard prevails along the

supply chain (Hobbs and Goddard, 2015). Many authors (Frewer et al., 1996; Ding et al., 2015; Lassoued and Hobbs, 2015) suggest that trust represents a solution for consumer decision making, especially when there is scarsity or lack of knowledge or this is hard to assess, as consumer buyer-seller relationships.

9

However, several studies (Trobe, 2001; Schneider, 2008; Tregear, 2011; Hartmann et al., 2015) found that the direct interactions between farmers and consumers as well as their repeated encounters can provide consumers with a sense of trust built especially on shared know-how and mutual understanding.

In relation to consumers’ necessity to trace food they eat, their

interest in knowing how, where and by whom food is produced has

been increasing over the last years. In line with this, the last two decades registered people’s growing skepticism that resulted in a qualitative shift of food habits and consumption patterns (Morris and Buller, 2003) known as reflexive consumerism (DuPuis, 2000; Ilbery and Maye, 2005; Sage, 2014; Starr, 2010). Such phenomena, indeed, materialized in a renewed critical and ethical consumer emphasis on notions such as food quality (e.g., seasonality, local origin, naturalness, freshness, organic production) and traceability, but also environmental sustainability, social embeddedness (Hinrichs, 2000; Kirwan, 2004; Sage, 2003), and some renewed farmer-related concerns such as fairness (Lusk and Briggeman, 2009) and trust (Hobbs and Goddard, 2015). As stated by Ilbery and Kneafsey (2000), nowadays global society witnesses an emphasized “renaissance of public interest in nature, nostalgia, local culture and culinary heritage”, that highlights a “renewed interest in so-called authentic, traditional, wholesome and traceable” food consumption.

10

Finally, this background deserves a brief mention to post-modern society and consumption patterns within which also marketing field can be recognized since 90s (Manel Hamouda and Abderrazak Gharbi, 2013). Post-modern consumption perspective experienced some changes during the last few decades. Interestingly, the rational consumer left room for an heterogeneous mix of purchasing motivations as: expressing individual ideas and values (e.g., around ethic or environment), communicating mind statements and building a new own identity, until happiness maximization and personal satisfaction through purchasing choices (Cicia et al., 2012).

Given this background, nowadays more sustainable food systems

are required by consumers to replace the old schemes all over the

world. In particular, what mentioned before has contributed to increasingly sparke consumer interest in alternative forms of food provision, e.g., seeking food that can be bought directly from the producer (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000).

Following consumer demand for more sustainable food products (Morris and Buller, 2003; Ilbery and Maye, 2005), the last two decades registered a rising proliferation of Short Food Supply

Chains (SFSCs) that are associated with sustainable production, as

opposite to global markets that is reliant upon industrial agriculture. As suggested by Galli and Brunori (2013), “the very concept of SFSCs emerged at the turn of the century” and “the point of departure of this debate is that, given that the prevailing trend in the agro-food system

11

is the development of ‘global value chains’ dominated by retailers and characterized by unequal distribution of power between the different actors, long distance trade and industrialized food, SFSCs are analysed and interpreted as a strategy to improve the resilience of the family farms with the support of concerned consumers, local communities and civil society organizations”.

Since the 90s, SFSCs became very popular all over Europe (Kneafsey et al., 2013) and in Italy as well (Marino and Cicatiello, 2012). However, as suggested also by Venn et al. (2006), there is a scarcity of information concerning the breadth and size of the SFSCs population all over the world, due to their extremely heterogeneity in natures and forms; accordingly, the most part of reports and studies focus on case studies that are frequently restricted to a particular region. The works of Brown (2002) and Low and Vogel (2011) represent an attempt to picture the exponential growth in the number of farmers’ markets and direct-selling in USA during the last years: estimated FMs passed from about 340 in 1970 to over 3000 in 2001. Focusing on direct selling, that represents one of the major component of SFSCs, nowadays the share of farms, mainly small farms, involved in direct sales is nearly 15% in European Union (EPRS, 2016) and 26% in Italy (ISTAT, 2010), whereas in USA direct-to-consumer sales account for 0.3% of all farm sales (Low et al., 2015).

As recently stated by Mundler and Laughrea (2016), who gather the position of scholars and experts around the world, SFSCs have

12

the potential to enhance the sustainability of conventional food systems, in terms of socio-economic equity and environmental and

local development. Accordingly, SFSCs represent a more

sustainable alternative to highly specialized and resource intensive

modern supply chains, that are perceived as untrustworthy and unsustainable by consumers (Wiskerke; 2009; Brunori et al., 2012; Forssell and Lankoski, 2014).

Defining SFSCs is not easy because of their great heterogeneity. Even at EU level there was no common definition of SFSCs until the new reform of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP 2014-2020). Accordingly, the current EU rural development policy (II Pillar) defined SFSCs for the first time within its Regulation (EU) No. 1305/2013 (article 2), as follows: “the term short supply chain means a supply chain involving a limited number of economic operators, committed to cooperation, local economic development, and close geographical and social relations between producers, processors and consumers”. Parker (2005) recognizes the following two characteristics of SFSCs: (1) the reduced geographical distance between production and consumption (i.e., reduced transportation distance known as food miles); (2) a small number of intermediaries between the producer and the consumer.

SFSCs involve geographically localized (rather than global) production, and consist in face-to-face interactions between farmers and consumers (Selfa and Qazi, 2005) who thus can easily interact and

13

share information (e.g., related to product origin or production process). Short-circuiting the conventional chains, SFSCs automatically reduce the number of commercial intermediaries, as in the traditional forms of past local markets: the number of intermediary actors between farmer and consumer is minimal or ideally nil and, by means of such reconnection between the actors, food is directly identified by and traceable to a farmer (Kneafsey et al., 2013). According to Holloway et al. (2007), repeated personal interactions also promote mutual understanding, and the dialogue exchange can encourage loyal relations (Tregear, 2011; Hartmann et al., 2015) that, in turn, are associated with consumers’ rediscovering food and understanding the identities of the producer as directly ‘present’ in the food they buy. It follows that consumers can make their own value-judgements (De-Magistris et al., 2014) and, as a result, the information exchange is found to reduce information asymmetry and re-establish personal trust (Schneider, 2008; Trobe, 2001). Some authors (Hallett, 2012; Kirwan, 2004) consider SFSCs having an increasing potential since their ability to respectively re-spatialise and re-socialise food (Hallett, 2012), by bringing consumers closer to the origin of food and envisaging a seller who is directly involved in the production process.

In addition, Goodman (2004) suggests that SFSCs embody a more endogenous, territorialized, ethical and ecological approach towards food products. In line with this, such short chains reflect the before

14

mentioned “quality turn” of consumers who increasingly look for food quality and traceability but also tradition and transparency, that are more guaranteed by short circuits instead of global, anonymous industrial production. Thus, by increasing food chain transparency, traceability is expected to increase consumer confidence in the food system (Menozzi et al., 2015).

According to Marsden et al. (2000) and Renting et al. (2003), SFSCs include mainly three different categories:

face- to-face initiatives (e.g. on-farm sales, farm shops, farmers’ markets);

spatially proximate initiatives, in which food is produced and retailed within the specific region of production;

spatially extended initiatives, where products are sold to

consumers that are located outside the production area.

With regard to SFSCs’ wide variety of typologies existing all over the world, it is possible to distinguish the following main forms:

on farm direct selling, that represents the simplest form and involves the direct transaction between farmer and consumer;

farmers' markets, that represent markets where agricultural products are directly sold by producers to consumers through a common marketing channel (Ragland and Tropp, 2009);

forms of partnerships between producers and consumers (often bound by a written agreement), as Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) or the Italian Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale (GAS). In particular,

15

GAS represent groups of consumers that together purchase food directly from producers (previously organized in local platforms) and that can benefit from convenient prices due to the absence of sale intermediaries;

box schemes, or home delivering of a pre-determined quantity of food (previously decided by consumers);

pick-your-own, where consumers purchase food directly from the farm, picking the products by themselves;

collective forms of direct selling (e.g., fairs, food festivals). According to a JRC report (Kneafsey et al., 2013), there is a tendency for SFSCs to sell organic and local products. In relation to products, perishable goods as fruit and vegetables are more suitable for sales at SFSCs (Low and Vogel, 2011; Martinez, 2015), followed by animal products and dairy products and beverages.

Although they are found to envisage a move back to traditional marketing made of face-to-face interactions, nowadays SFSCs represent alternative niches of food production, distribution and consumption. Some authors (Tregear et al., 2007; Aubry and Kebir, 2013; Knezevic et al., 2013; O’Neill, 2014) define SFSCs as expression of cultural capital and consider they can be an engine for territorial development (income growth and territorial value added) both in rural and in peri-urban areas. Their development, indeed, can be considered as an important opportunity for the Italian food sector: SFSCs are particularly suited to the highly fragmentation of Italian

16

agricultural production, as they involve above all small producers, being also an engine for the promotion of a wide range of traditional, local food which are representative of the territorial different rural tradition, knowledge and culture.

In order to explain their sustainability promise, a brief summary of SFSCs’ impacts follows, although the reader may refer especially to the fifth chapter for a more accurate dissertation on this. SFSCs’ impact refer to all the three dimensions of sustainability, as stated by the Brundtland Report (United Nations, 1987). First of all, SFSCs contribute to social sustainability by ensuring new direct relations between producers and consumers that do not merely concern the economic nature of market exchange: they also actively contribute to both customers’ personal gratification (due to the pleasant purchasing atmosphere and purchasing-related cultural and social benefits) and social cohesion and community development, by reconnecting people that share common interests and values (e.g., the preservation of typical products, local knowledge and traditions) and establishing new trust around food.

With regard to environmental sustainability, SFSCs reduce the use of input (non-renewable fossil energy, water, fertilizer, etc.), packaging and transports (e.g., products are locally produced and are fresh and seasonally sold), and valorize typical products (i.e., biodiversity).

17

Finally, SFSCs also contribute to many economic sustainability goals as: the creation of new employment in agriculture; the support to farmers’ diversification and innovation and the possibility to achieve a good standard of living for farmers and their families; finally, the promotion of local economies and tourism, especially in marginal and rural areas, to retain rural livelihood (DuPuis and Goodman, 2005). In line with this, SFSCs let rural areas retain their autonomy and produce evenly distributed welfare, thus contributing to the economic sustainability of communities. Contrary to standard long food supply chains, where only a small proportion of total added value is captured by primary producers, short chains have the capacity to increase farmers’ income by ensuring a fair price for them. To this respect, a recent Eurobarometer survey (EU, 2016) confirms the propensity of European consumers to support local agriculture and economy by purchasing goods at a fair price, in order to strengthen farmer’s role in the food chain (EPRS, 2016). Indeed, selling agricultural products directly to consumers enables producers to retain a greater share of the products' market value (through the elimination of intermediaries) and to potentially increase their income. As a consequence, the “iron law” (i.e., the strong dependence) of price is displaced by different considerations that make consumers feel embedded while purchasing (Hinrichs et al., 2004).

However, although the global envisages the unsustainability of modern food sector, many authors consider that the local does not

18

always imply better performances, especially because of lower volumes, as in terms of energy use, environmental impact and transportation costs (Schlich et al., 2006; Coley et al., 2011).

Food consumption represents also a major issue in sustainability political strategies because of its impacts on environment, economy and society (e.g. public health). Thus, in addition to consumers, SFSCs have spurred the interest of governments. In line with this, the new European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 2014-2020 encourages the promotion of SFSCs for the first time through a specific financial support within its second pillar, in order to provide a publicly funded stimulus for sustainable development. In particular, several measures co-financed by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) will support SFSCs, as explicitly recognized by one of the new six priorities and a thematic sub-programme. In particular, Priority three is related to the promotion of food chain organization, and one of its Focus Areas (3A) specifically refers to the promotion of local markets and short supply circuits in order to improve the competitiveness of primary producers.

Many authors (Govindasamy and Nayga, 1996; Kloppenburg et al., 2000; Toler et al., 2009; Tregear, 2011; Kneafsey et al., 2013; Galli et al., 2015; Hughes and Isengildina-Massa, 2015; Mundler and Laughrea, 2016) found that there is a wide variety of motivations that lead consumer to seek for alternative food chains; among other, purchasing products with higher quality standards (freshness,

19

nutritional value) or produced with a more environmentally-friendly method, pursuing an healthy diet and achieving more direct interactions with the grower, in order to know the origin of food and also to support local agriculture and economy by purchasing products at a fair price.

In this context, SFSCs’ growing appeal seems to reflect recent developments in post-modern society and consumption patterns as, in addition to proper food necessity, nowadays consumers seek for food quality and traceability but also ethical and environmental outcomes in the product they buy, in order to maximize their happiness function rather than their utility function.

A related more complete dissertation is available through the following chapters. However, there is still a lack of an extensive and comprehensive assessment of such motivations, in order to process knowledge in such flourishing alternative marketing systems.

The lack of a comprehensive knowledge of consumer perspective and decision making towards SFSCs in Italy has encouraged this research that aims at contributing to the growing literature on such alternative food networks, focusing on the investigation of consumer preferences and behaviour towards purchasing food at SFSCs. In particular, the work explores the importance of some major drivers in influencing consumers’ preferences for such alternative sales schemes. Afterwards, based on some preliminary findings, it focuses on investigating some aspects (i.e., sustainability, trust, fairness) more in

20

depth. This research thesis aims at providing an organic body where every single chapter contributes to have a broader view on the topic as a whole, following the three years long doctoral path.

The research activity followed two main approaches and related methodologies:

1. The explorative analysis of the major determinants of consumer preferences for purchasing food at SFSCs, instead of conventional markets. It was performed through the application of a socio-psychological approach, i.e. the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991). TPB represents one of the most popular and widely cited contemporary alternative approach to predict and explain a wide variety of human behaviours (Ajzen, 2015) as consumers’ food choices and purchasing preferences (Cook et al., 2002; Verbeke and Vackier, 2005). This research represents the first application ever of TPB to consumer preferences related to SFSCs.

2. Based on the previous qualitative findings related to SFSCs’ category in general, this research has investigated more in depth the role of some specific concerns (i.e., sustainability, trust and fairness) in influencing Italian consumers’ purchasing preferences for farmers’ markets (FMs), that represent a major component of SFSCs (Marino and Cicatiello, 2012). To this purpose, the research turned to behavioural economics, performing a choice experiment (CE) based on an hypothetical market situation and focusing on the two most

21

common goods sold at SFSCs (i.e., vegetables and fruits) as apples and lettuce.

The use of two different research approaches turns out to be in line with current purchasing motivations that lie in postmodern contemporary consumption and its interdisciplinary nature (Miles, 1999), reflecting the current attempt of researchers who, according to Firat (1991), “are at the forefront of major leaps in methodological and theoretical movements in this field”.

Against the background of this research topic there is the aim of providing new knowledge around such alternative supply chains’ growing appeal among consumers, in order to explain their recent increasing in number, especially in Italy but not only.

In relation to the first approach, according to Ajzen 2015) the Theory of Planned Behaviour does not rely on the “overall evaluation or utility of a product or a service”, but it “focuses on the specific behaviour of interest”, providing a comprehensive framework to explain and understand its determinants. On the contrary, with the second approach this research referred to Random Utility Theory (McFadden, 1974) to estimate consumer preferences from a choice experiment, that reminds to Lancaster’s (1966) exposition on consumer theory, who states that consumer utility is not derived directly from the goods consumed but from their attributes.

22

To conclude, the work proceeds with the following six papers that correspond to chapters:

1. Exploring consumers’ attitude towards purchasing in Short Food Supply Chains.

Published in 2015 on “Quality - Access to Success”, Vol. 16, pp. 135-141

2. Comparing Italian and Brazilian consumers’ attitudes towards Short Food Supply Chains.

Published in 2016 on “Rivista di Economia Agraria”, Vol. 71(1 - Supplemento), pp. 246-254. doi:10.13128/REA-18644

3. Exploring consumers’ behaviour towards Short Food Supply Chains.

Published in 2016 on “British Food Journal”, Vol. 118(3), pp. 618 - 631. doi:10.1108/BFJ-04-2015-0168

4. Telling the trust about consumer behaviour: a Theory of Planned Behaviour perspective to investigate factors influencing consumer purchase at Short Food Supply Chains.

5. Consumers’ sense of Farmers’ Markets: tasting

sustainability or just purchasing food?

Published in 2016 on “Sustainability”, Vol. 8, 1157. doi:10.3390/su8111157

6. Heterogeneity in consumers’ preferences for Farmers’ Markets: a comparative analysis among Italian and German consumers.

23

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 50, 179-211.

Ajzen, I. (2015). Consumer attitudes and behaviour: the theory of planned behaviour applied to food consumption decisions. Rivista di Economia Agraria, 70(2), 121-138.

Assefa, T.T., Meuwissen, M.P., Oude Lansink, A.G.P.M. (2013). Literature review on price volatility transmission in food supply chains, the role of contextual factors and the CAP’s market measures (No. 4). Working paper.

Aubry, C., Kebir, L. (2013). Shortening food supply chains: A means for maintaining agriculture close to urban areas? The case of the French metropolitan area of Paris. Food Policy, 41, 85-93.

Brown, A. (2002). Farmers' market research 1940-2000: An inventory and review. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 17(04), 167-176.

Brunori, G., Rossi, A., Guidi, F. (2012). On the new social relations around and beyond food. Analysing consumers' role and action in

Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale (Solidarity Purchasing

Groups). Sociologia Ruralis, 52(1), 1-30.

Cicia, G., Cembalo, L., Del Giudice, T., Verneau, F. (2012). Il sistema agroalimentare ed il consumatore postmoderno: nuove sfide per la ricerca e per il mercato. Economia Agro-Alimentare, 1, 117-142.

24

Coley, D., Howard, M., Winter, M. (2011). Food Miles: Time for a Re-Think?. British Food Journal, 113 (7), 919-934.

Cook, A.J., Kerr, G.N., Moore, K. (2002). Attitudes and intentions towards purchasing GM food. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23, 557-572.

De Magistris, T., Del Giudice, T., Verneau, F. (2015). The effect of information on willingness to pay for canned tuna fish with different corporate social responsibility (CSR) certification: a pilot study. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 49(2), 457-471.

Ding, Y., Veeman, M.M., Adamowicz, W.L. (2015). Functional food choices: Impacts of trust and health control beliefs on Canadian consumers’ choices of canola oil. Food Policy, 52, 92-98.

DuPuis M., Goodman, D. (2005). Should we go home to eat?: toward a reflexive politics of localism. Journal of Rural Studies, 21(3), 359-371.

DuPuis, E.M. (2000). Not in my body: BGH and the rise of organic milk. Agriculture and human values, 17(3), 285-295.

European Commission (2013). Commission Staff Working Document on Various Aspects of Short Food Supply Chains Accompanying the Document Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the Case for a Local Farming a ND Direct Sales Labelling Scheme; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium.

25

European Commission (2013). Commission Staff Working Document on Various Aspects of Short Food Supply Chains Accompanying the Document Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the Case for a Local Farming a ND Direct Sales Labelling Scheme; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium.

European Parliamentary Research Service (2016). Short food supply chains and local food systems in the EU; Marie-Laure Augère-Granier; Members' Research Service. PE 586.650

European Union (2016). Special Eurobarometer 440 European, Agriculture and the CAP January 2016 Report; ISBN 978-92-79-54246-6. doi:10.2762/03171

Firat, A.F. (1991). The consumer in Postmodernity. NA-Advances in Consumer Research, 18, 70-76.

Forbes, S.L., Cohen, D.A., Cullen, R., Wratten, S.D., Fountain, J. (2009). Consumer attitudes regarding environmentally sustainable wine: an exploratory study of the New Zealand marketplace. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(13), 1195-1199.

Forssell, S., Lankoski, L. (2014). The sustainability promise of alternative food networks: An examination through “alternative characteristics”. Agriculture and Human Values, 32, 63-75.

Frewer, L.J., Howard, J.C., Hedderley, D., Shepherd, R. (1996). What Determines Trust in Information About Food-Related Risks? Underlying Psychological Constructs. Risk Analysis, 16(4), 473-486.

26

Galli, F., Bartolini, F., Brunori, G., Colombo, L., Gava, O., Grando, S., Marescotti, A. (2015). Sustainability assessment of food supply chains: an application to local and global bread in Italy. Agricultural and Food Economics, 3(1), 1.

Galli, F., Brunori, G. (2013). Short Food Supply Chains as drivers of sustainable development. Evidence Document. Document developed in the framework of the FP7 project FOODLINKS (GA No. 265287). Laboratorio di studi rurali Sismondi, ISBN 978-88-90896-01-9.

Goodman, D. (2004). Rural Europe redux? Reflections on alternative agro‐food networks and paradigm change. Sociologia ruralis, 44(1), 3-16.

Govindasamy, R., Nayga Jr, R.M. (1996). Characteristics of farmer-to-consumer direct market customers: An overview. Journal of Extension, 34(4).

Hallett, L.F. (2012). Problematizing local consumption: is local food better simply because it’s local?. American International Journal of Contemporary research, 2(4), 18-29.

Hamouda, M., Gharbi, A. (2013). The postmodern consumer: an identity constructor?. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 5(2), 41.

Hartmann, M., Klink, J., Simons, J. (2015). Cause related marketing in the German retail sector: Exploring the role of consumers’ trust. Food Policy, 52, 108-114.

27

Hinrichs, C.C. (2000). Embeddedness and local food systems: notes on two types of direct agricultural market. Journal of rural studies, 16(3), 295-303.

Hinrichs, C.C., Gulespie, G.W., Feenstra, G.W. (2004). Social learning and innovation at retail farmers' markets. Rural sociology, 69(1), 31-58.

Hobbs, J.E., Goddard, E. (2015). Consumers and trust. Food Policy, 52, 71–74.

Holloway, L., Kneafsey, M. (2000). Reading the space of the farmers' market: a preliminary investigation from the UK. Sociologia Ruralis, 40(3), 285-299.

Holloway, L., Kneafsey, M., Venn, L., Cox, R., Dowler, E., Tuomainen, H. (2007). Possible Food Economies: a Methodological

Framework for Exploring Food Production–Consumption

Relationships. Sociologia Ruralis, 47(1), 1-19.

Hughes, D.W., Isengildina-Massa, O. (2015). The economic impact of farmers’ markets and a state level locally grown campaign. Food Policy, 54, 78-84.

Ilbery, B., Kneafsey, M. (2000). Registering regional speciality food and drink products in the United Kingdom: The case of PDOs and PGls, Area, 32(3), 317-325.

Ilbery, B., Maye, D. (2005). Food supply chains and sustainability: evidence from specialist food producers in the Scottish/English borders. Land Use Policy, 22(4), 331-344.

28

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica - ISTAT (2010). VI Censimento

Agricoltura Italia. Available at:

http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it/Index.aspx

Kirwan, J. (2004). Alternative strategies in the UK agro‐food system: interrogating the alterity of farmers' markets. Sociologia Ruralis, 44(4), 395-415.

Kloppenburg, Jr J., Lezberg, S., De Master, K., Stevenson, G., Hendrickson, J. (2000). Tasting food, tasting sustainability: Defining the attributes of an alternative food system with competent, ordinary people. Human organization, 59(2), 177-186.

Kneafsey, M., Venn, L., Schmutz, U., Balázs, B., Trenchard, L., Eyden-Wood, T., Bos, E., Sutton, G. (2013). Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU. A State of Play of Their Socio-Economic Characteristics; European Commission Joint Research Centre: Seville, Spain.

Knezevic, I., Landman, K., Blay-Palmer, A. (2013). Local Food Systems-International Perspectives. Review of literature, research projects and community initiatives. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Available on line: http://www.

nourishingontario.

ca/wpcontent/uploads/2013/07/EUAntipode-FoodHub-LitReview-2013. pdf.

Lancaster, K.J. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. The Journal of Political Economy, 132-157.

29

Lassoued, R., Hobbs, J.E. (2015). Consumer confidence in credence attributes: The role of brand trust. Food Policy, 52, 99-107.

Low, S., Vogel, S. (2011). Direct and Intermediated Marketing of Local Foods in the United States; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA.

Low, S.A., Adalja, A., Beaulieu, E., Key, N., Martinez, S., Melton, A., Perez, A., Ralston, K., Stewart, H., Suttles, S., Jablonski, B.B.R., Vogel, S. (2015). Trends in US local and regional food systems: A report to Congress (Administrative Publication No. AP-068). Washington, DC: USDA. Economic Research Service.

Lusk, J.L., Briggeman, B.C. (2009). Food values. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 91(1), 184-196.

Marino, D., Cicatiello, C. (2012). I Farmers’ Market: La Mano Visibile del Mercato. Aspetti Economici, Sociali e Ambientali delle Filiere Corte; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy.

Marsden, T., Banks, J., Bristow, G. (2000). Food supply chain approaches: exploring their role in rural development. Sociologia Ruralis, 40(4), 424-438.

Martinez, S.W. (2015). Fresh Apple And Tomato Prices At Direct Marketing Outlets Versus Competing Retailers In The US Mid-Atlantic Region. Journal of Business & Economics Research (Online), 13(4), 241.

30

McFadden, D. (1974). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In Frontiers in Econometrics; Zarembka, P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA; 1, 105-142.

Menozzi, D., Halawany-Darson, R., Mora, C., Giraud, G. (2015). Motives towards traceable food choice: A comparison between French and Italian consumers. Food Control, 49, 40-48.

Meyer, S.B., Coveney, J., Henderson, J., Ward, P.R., Taylor, A.W. (2012). Reconnecting Australian consumers and producers: identifying problems of distrust. Food Policy, 37(6), 634-640.

Miles, S. (1999). A pluralistic seduction: Postmodernism at the crossroads. Consumption, Culture and Markets, 3, 145-163.

Morris, C., Buller, H. (2003). The local food sector: a preliminary assessment of its form and impact in Gloucestershire. British Food Journal, 105(8), 559-566.

Mundler, P., Laughrea, S. (2016). The contributions of short food supply chains to territorial development: A study of three Quebec territories. Journal of Rural Studies, 45, 218-229.

Mundler, P., Rumpus, L. (2012). The energy efficiency of local food systems: A comparison between different modes of distribution. Food Policy, 37(6), 609-615.

O’Neill, K. (2014). Localized food systems–what role does place play?. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 1(1), 82-87.

31

Parker, G. (2005). Sustainable Food? Teikei, Co-Operatives and Food Citizenship in Japan and the UK; University of Reading: Reading, UK.

Ragland, E., Tropp, D. (2009). USDA National Farmers Market Manager Survey 2006; Agricultural Marketing Service, USDA: Washington, DC, USA.

Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005.

Reisch, L., Eberle, U., Lorek, S. (2013). Sustainable food consumption: an overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustainability: Science, Practice, & Policy, 9(2), 7-25.

Renting, H., Marsden, T.K., Banks, J. (2003). Understanding alternative food networks: exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environment and Planning, 35(3), 393-411.

Sage, C. (2003). Social embeddedness and relations of regard: alternative ‘good food’networks in south-west Ireland. Journal of Rural Studies, 19(1), 47-60

Sage, C. (2014). The transition movement and food sovereignty: From local resilience to global engagement in food system transformation. Journal of Consumer Culture, 14(2), 254-275.

32

Schlich, E., Biegler, I., Hardtert, B., Luz, M., Schroder, S., Scroeber, J., Winnebeck, S. (2006). La consommation alimentaire d’énergie finale de différents produits alimentaires: un essai de comparaison. Courrier de l’environnement de l’INRA, 53, 111-120.

Schneider, S. (2008). Good, clean, fair: The rhetoric of the slow food movement. College English, 70(4), 384-402.

Selfa, T., Qazi, J. (2005). Place, taste, or face-to-face? Understanding producer-consumer networks in “local” food systems in Washington State. Agriculture and Human Values, 22(4), 451-464.

Starr, A. (2010). Local food: a social movement? Cultural Studies↔ Critical Methodologies. 10, 479–490.

Tangermann, S. (2011). Policy Solutions to Agricultural Market Volatility: A Synthesis; ICTSD Programme on Agricultural Trade and Sustainable Development, Issue Paper No. 33, ICTSD International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, Geneva, Switzerland.

Thomas, L.N., Mcintosh, W.A., (2013). “It Just Tastes Better When It’s In Season”: Understanding Why Locavores Eat Close to Home. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 8, 61-72.

Thorsøe, M., Kjeldsen, C. (2015). The Constitution of Trust: function, configuration and generation of trust in alternative food networks. Sociologia Ruralis, 56, 157–175.

Toler, S., Briggeman, B.C., Lusk, J.L., Adams, D.C. (2009). Fairness, farmers markets, and local production. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 91(5), 1272-1278.

33

Tregear, A. (2011). Progressing knowledge in alternative and local food networks: Critical reflections and a research agenda. Journal of Rural Studies, 27(4), 419-430.

Tregear, A., Arfini, F., Belletti, G., Marescotti, A. (2007). Regional foods and rural development: the role of product qualification. Journal of Rural Studies, 23(1), 12-22.

Trobe, H.L. (2001). Farmers’ markets: consuming local rural produce. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 25, 181-192.

United Nations (1987). Our Common Future-Brundtland Report; Oxford University: Oxford, UK.

Venn, L., Kneafsey, M., Holloway, L., Cox, R., Dowler, E., Tuomainen, H. (2006). Researching European ‘alternative’food networks: some methodological considerations. Area, 38(3), 248-258.

Verbeke, W., Vackier, I. (2005). Individual determinants of fish consumption: application of the theory of planned behavior. Appetite, 44(1), 67-82.

Wiskerke, J.S. (2009). On places lost and places regained: Reflections on the alternative food geography and sustainable regional development. International Planning Studies, 14(4), 369-387.

34

CHAPTER 1

EXPLORING CONSUMERS’ ATTITUDE TOWARDS PURCHASING IN SHORT FOOD SUPPLY CHAINS

Elisa GIAMPIETRIa, Adele FINCOa, Teresa DEL GIUDICEb

a Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences (3A) - Università Politecnica delle Marche, via Brecce Bianche 60131, Ancona, Italy

b Department of Agricultural Sciences - Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, via Università 80055, Napoli, Italy

Published in 2015 on “Quality - Access to Success”, Vol. 16, pp. 135-141.

ABSTRACT

This work investigates consumers’ attitudes that influence the intention to buy food in Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs), instead of conventional market chains. A review of relevant literature summarizes research concerning SFSCs’ meanings and impacts. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, a survey was carried out among university students in Italy in order to validate a pilot questionnaire and test attitudinal variables having significant effect

35

on behavioral intention linked to SFSCs’ preference. Results show that sustainability, convenience and local development play a key role in the intention that drives short chains’ shopping preferences.

KEYWORDS

Short Food Supply Chains, Theory of Planned Behavior, Consumers’ Attitudes, Principal Component Analysis

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, intensive agriculture, industrial food production and consumer’s new habits have changed the original scenario of food production, distribution and consumption. Furthermore, with the introduction of modern food distribution systems, the direct link farming-food and thus farmers-consumers vanished and the consumer trust declined more and more. Bringing farmers and consumers closer, Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) seem to be considered as a sustainable alternative to global markets in terms of economical, social and environmental benefits. In order to meet rising consumer demand, in recent years SFSCs gained a growing foothold across Europe so that nowadays EU rural development strategies (CAP 2014-2020) support SFSCs as one of the new six priorities as well as a thematic sub-programme to which address specific needs. According to this, studying consumers’ attitudes towards and intention to purchase in SFSCs become primarily important. Following this vein, this preliminary study aims to explore the attitudinal beliefs that

36

underlie the growing consumers’ interest to purchase in the SFSCs. According to Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior, we conducted a pilot survey in order to elucidate which are the most significant variables associated with consumers’ attitude, that is a reliable predictor of intention. Finally, a semantic differential was built on the previous variables and a PCA condensed the items into a small set of principal components driving the intention under investigation.

SHORT FOOD SUPPLY CHAINS: A BRIEF REVIEW

In recent years, a renewed interest and a significant growth in alternative agri-food networks (AAFNs) grew as opposite to the conventional markets, creating new direct interactions and relations between producers and consumers that do not merely concern economic nature of market exchange. In this context, the turn to more sustainable farming methods, the creation of local and shorter food supply chains and the reflexive consumerism materialized (Marsden et al., 2000; Morris and Buller, 2003). Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) play a key role in such emerging food networks, representing traditional or alternative niches of producing, distributing, retailing, and buying food, compared to the dominating agro-industrial model. SFSCs consist in face-to-face interactions between producers and consumers who thus can easily interact and share information on the product origin and its production process, so that consumers can make their own value-judgements (D’Amico et al., 2014a and 2014b;

De-37

Magistris et al., 2014). Short-circuiting the conventional chains, SFSCs automatically reduce the number of commercial intermediaries, as in the traditional forms of past local markets. These alternative food networks are heterogeneous in nature and practice, including mainly three different categories (Renting et al., 2003): “face- to-face” initiatives (e.g. on-farm sales, farm shops, farmers’ markets); “spatially proximate” initiatives, in which food is produced and retailed within the specific region of production; finally, “spatially extended” initiatives, where products are sold to consumers located outside the production area. Although the multiple forms of short chains (direct selling, box schemes, farmers’ markets, pick-your-own, on-farm sales, consumer cooperatives, direct internet sales, community supported agriculture, e-commerce, etc.), SFSCs can have many impacts (Cicatiello et al., 2012; Brunori and Bartolini, 2013; Galli and Brunori, 2013; Gava et al., 2014; Schmid et al., 2014): i.e. economic sustainability, environmental sustainability, social sustainability, impact on health (food quality and wellbeing), and ethical impact. According to Goodman (2004), SFSCs nowadays embody a more endogenous, territorialized, ethical and ecologically embedded approach towards food products. These circuits are considered to be the most appropriate channels for organic products, local and small-scale production family (Kneafsey et al., 2013). SFSCs also re-socialise and re-spatialise food (Hallett, 2012). In fact, local food can be an engine for territorial development (income

38

growth and territorial value-added) both in rural and in peri-urban areas (Tregear et al., 2007; Aubry and Kebir, 2013; Knezevic et al., 2013; O'Neill, 2014), becoming expression of cultural capital and rural embeddedness (Hinrichs, 2000; Sage, 2003; Kirwan, 2004). In the post-modern society, market becomes an opportunity to express individual ideas and values (of ethical and environmental nature). According to this, consumption becomes itself a vector for consumer to build a new own identity, to communicate mind statements, to satisfy his own mood and personality, to be recognized and included by other people, until to maximize his own happiness through purchasing choises (Cicia et al., 2012). In line with this, short chains seem to perfectly reflect the “quality turn” of post-modern consumer who increasingly looks for food quality and traceability (Panico et al., 2014; Scozzafava et al., 2014; Verneau et al., 2014) but also tradition and transparency, that are more guaranteed by short circuits in spite of global industrial production. From the side of producers, they can recapture their value in the supply chain in order to increase their income (Verhaegen and Van Huylenbroeck, 2001; Belletti et al., 2010), so that SFSCs can embody a possible solution to the economic sustainability of farm. In addition, new solid loyalty and trust relationships can be built, sharing personal values and ethics including the responsible management of common goods as environmental resources (La Barbera et al., 2014; Migliore et al., 2014). According to this, Ilbery and Maye (2005) argue that SFSCs serve as a means of

39

saving energy and reducing food miles, of getting biodiversity from farm to plate, of providing social care and improving civic responsibility, and of retaining economic value in a local economy.

DATA AND METHODS

In the field of studies on consumer behavior, different techniques have been proposed and gradually developed. The paper turns to social psychology and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991). TPB is one of the most popular contemporary theory designed to predict and explain a wide variety of human behavior as post-modern consumers’ purchasing preferences. According to the TPB, a specific behavior is determined by a combination of intention and perception of control over performing behavior. Furthermore, TPB identifies three global variables (attitude towards the behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control) that together contribute to the creation of the intention; moreover, behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs and control beliefs are reliable variables predictors. In order to highlight significant attitude beliefs that influence the intention to buy food in Short Food Supply Chains, we carried out a preliminary exploratory research built on a TPB pilot questionnaire, whose items were defined taking into account Ajzen’s conceptual and methodological considerations for constructing a TPB questionnaire (Ajzen, 2006). Data were collected in December 2014 by directly interviewing a representative pilot sample (Depositario et al., 2009) of

40

60 university students (n = 60) from the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at Università Politecnica delle Marche in Italy. Respondents were asked to express their opinion about SFSCs, eliciting readily accessible attitudinal variables that are necessary to formulate a future questionnaire commensurate with the TPB, in view of further applications. The pilot questionnaire consisted of 12 questions divided into three parts: the first comprising 3 open-ended behavioral questions adapted from TPB and linked to attitudinal investigation, the second part includes a semantic differential designed to investigate all the attitudinal variables, the last section encloses up to 8 socio-demographic questions describing the sample. Of all the students interviewed (Tab.1), 52 percent are female, 90 percent are Italian and 45 percent have already graduated. Approximately 62 percent live in urban areas while 32 percent in rural areas, where the distribution of direct sales’ activities is widespread. Finally, 63 percent admited to go personally grocery shopping and 80 percent buy organic products. As stated before, consumers’ attitudes were collected by means of 3 open-ended questions (Tab.2) adapted from the TPB that have been elaborated through a content analysis. These questions are built on the following structure: the first (Q1 - What do you see as the advantages of buying in local Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) during the daily shopping?) relates to the advantages of SFSCs; the second one (Q2 - What do you see as the disadvantages of buying in local Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) during the daily shopping?) investigates the

41

disadvantages; the last one (Q3 - What else comes to mind when you think about buying in local Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) during the daily shopping?) explores any other aspect of SFSCs meditated by the interviewees. Attitudes have been collected by means of a content analysis since several categories have been identified as variables through deductive extraction (Weber, 1990; Losito, 2007), based both on the exact wording used in the answers and on SFSCs’ literature. Moreover, we reported the frequency with which variables appeared in the text suggesting the magnitude of this observation, and we aggregated them into principal components through a logical-semantic approach. On the basis of this explorative pilot survey, we structured all the extracted items in a seven-point semantic differential with anchor points 1 = strongly agree to 7 = strongly disagree. We used a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with orthogonal (Varimax) rotation, in order to condense consumers’ responses from the original 36 items into a smaller set of principal dimensions (PC), according to correlations among items. We also scrutinized all the variables according to their Cronbach’s alpha coefficient that measures internal consistency of items in order to gauge their reliability. Alpha coefficient ranges in value from 0 to 1: according to Ajzen, we indicated 0.7 to be an acceptable reliability coefficient.

42

Table 1. Sample descriptive statistics

VARIABLE MEAN (%) STD. DEV.

Gender: female 51,7% 1,62

Nationality: italian 90,0% 2,51

Education: graduated 45,0% 2,32

Residence: rural 31,7% 2,23

Household net income: 25.000-50.000€ 41,7% 2,99 Number of household members: 4 units 43,3% 1,89 To go personally grocery shopping: yes 63,3% 1,21

Buying organic: yes 80,0% 1,05

RESULTS

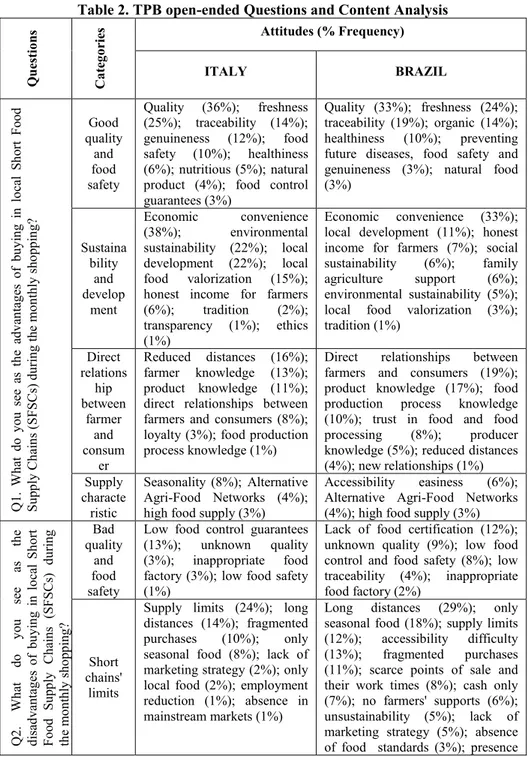

A total of 60 interviewees gave complete answers to the behavioral questions. By means of a content analysis, we extracted the most frequently named attitudes associated with consumers’ SFSCs shopping intention (Tab. 2), thus condensing them into some principal categories. The three questions (Q1, Q2, Q3) aimed to extrapolate the interviewees’ self-revealed variables related to consumers’ attitudes. According to the advantages of SFSCs (Q1), product good quality (quality, 37%; freshness, 23%; authenticity, 10%; traceability, 10%), sustainability (economic convenience, 37%; local development, 30%) and the direct relationship between consumers and producers (producer confidence, 13%; product knowledge, 12%) seem to be the most relevant variables’ categories. On the contrary, product bad quality (low food control guarantees, 14,3%), short chains’ limits (low supply capacity, 35%; long distances, 18%; consumers’ lack of time for shopping, 12%) and economic inconvenience (31%) seem to prevent the intention towards buying at SFSCs. Six main categories have been selected inside the third question (Q3), many of which have

43

already been extracted in the previous set of questions; they are convenience, food quality, sustainability (rural development, 9,8%), local-food valorization (traditions, 7,3%; niche products, 2,4%; local food, 2,4%; rural embeddedness, 2,4%), direct relationships between consumers and producers (friendship, 4,9%; reciprocal trust, 2,4%) and finally short sale aspects (improving sale management, point of sale research, farmers’ markets, e-commerce).

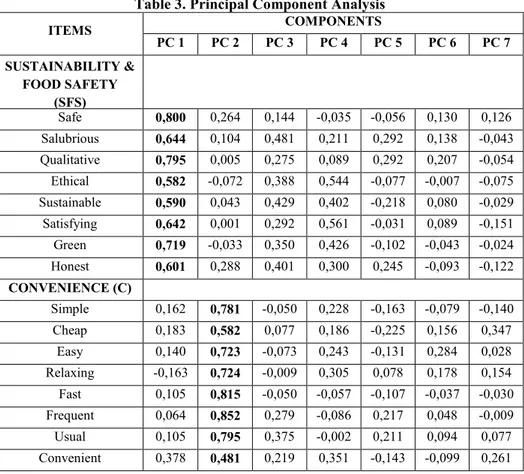

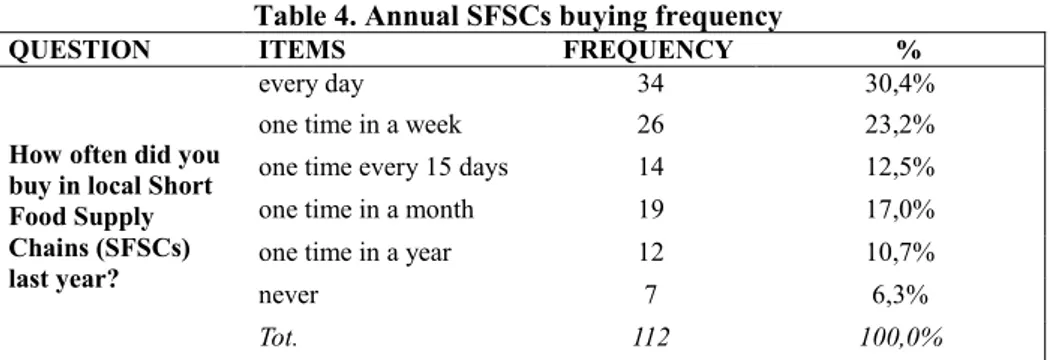

Afterwards, we structured a semantic differential on the basis of the categories previously extracted by content analysis from pilot survey. According to correlations, PCA recombined items’ dimensions into 7 principal components (Tab.3). Among these, results show that sustainability (SFS; α = 0,936), convenience (C; α = 0,900) and local development (LD; α = 0,905) are found to be the most significant predictors of SFSCs’ shopping intention, since they explain up to 57,4% of total variance. Nevertheless, some other important information emerge by means of the other extracted principal components related to consumers’ SFSCs shopping attitudes, as future research suggestions: gratifying (G; α = 0,879); localty (L; P value = 0,479); pleasantness (P; P value = 0,607); finally, another component (C7) with a strong inverse relationship (P value = -0,151) between its two variables.

According to sustainability (S), that explains about 39 percent of variance, it is characterized by some 8 items expressing both consumers’ attitude towards food safety and health care (e.g. safe,

44

salubrious, qualitative) and consumers’ sensitivity towards the environmental (e.g. sustainable, green) and social (e.g. ethical, satisfying, honest) sustainability of SFSCs.

Table 2. TPB open-ended questions

QUESTIONS COMPONENTS VARIABLES (%)

Q1 - What do you see as the advantages of buying in local Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) during the daily shopping?

Good quality quality (37%); freshness (23%); authenticity (10%); traceability (10%)

Sustainability economic convenience (37%); local development (30%)

Direct relationship

producer confidence (13%); product knowledge (12%)

Q2 - What do you see as the disadvantages of buying in local Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) during the daily shopping?

Bad quality low food control guarantees (14,3%); unknown quality (6,1%)

Short chains' limits

low supply capacity (35%); long distances (18%); consumers’ lack of time for shopping

(12%) Economic

inconvenience economic inconvenience (31%)

Q3 - What else comes to mind when you think about buying in local Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) during the daily shopping?

Convenience inconvenience (7,3%); convenience (2,4%) Food quality quality (19,5%); freshness (7,3%) Sustainability rural development (9,8%)

Local food valorization

traditions (7,3%); niche products (2,4%); local food (2,4%); rural embeddedness (2,4%) Direct

relationship friendship (4,9%); reciprocal trust (2,4%)

Short sale aspects

farmers' markets (4,9%); improving sale management (2,4%); research of point of sale

45

Social sustainability is related to direct relationships between consumers and producers, in other words the theme of embeddedness that sums up the reciprocal interaction and dialogue exchange among consumers and producers, engine of values sharing and creation of trust and ethical relations. Direct contact also prevents information asymmetry on food safety by means of consumer’ acquiring more information on the product and its production process, thus becoming a stimulus to SFSCs affiliation.

Table 3. Principal Component Analysis

ITEMS COMPONENTS PC 1 PC 2 PC 3 PC 4 PC 5 PC 6 PC 7 SUSTAINABILITY & FOOD SAFETY (SFS) Safe 0,800 0,264 0,144 -0,035 -0,056 0,130 0,126 Salubrious 0,644 0,104 0,481 0,211 0,292 0,138 -0,043 Qualitative 0,795 0,005 0,275 0,089 0,292 0,207 -0,054 Ethical 0,582 -0,072 0,388 0,544 -0,077 -0,007 -0,075 Sustainable 0,590 0,043 0,429 0,402 -0,218 0,080 -0,029 Satisfying 0,642 0,001 0,292 0,561 -0,031 0,089 -0,151 Green 0,719 -0,033 0,350 0,426 -0,102 -0,043 -0,024 Honest 0,601 0,288 0,401 0,300 0,245 -0,093 -0,122 CONVENIENCE (C) Simple 0,162 0,781 -0,050 0,228 -0,163 -0,079 -0,140 Cheap 0,183 0,582 0,077 0,186 -0,225 0,156 0,347 Easy 0,140 0,723 -0,073 0,243 -0,131 0,284 0,028 Relaxing -0,163 0,724 -0,009 0,305 0,078 0,178 0,154 Fast 0,105 0,815 -0,050 -0,057 -0,107 -0,037 -0,030 Frequent 0,064 0,852 0,279 -0,086 0,217 0,048 -0,009 Usual 0,105 0,795 0,375 -0,002 0,211 0,094 0,077 Convenient 0,378 0,481 0,219 0,351 -0,143 -0,099 0,261

46 ITEMS COMPONENTS PC 1 PC 2 PC 3 PC 4 PC 5 PC 6 PC 7 LOCAL DEVELOPMENT (LD) Useful 0,346 0,097 0,626 0,220 0,041 0,432 -0,081 Local 0,127 -0,133 0,839 0,178 0,216 0,064 0,023 Aware 0,298 0,144 0,738 0,390 -0,030 -0,158 0,141 Important 0,303 0,165 0,739 0,298 -0,086 0,238 -0,057 Necessary 0,276 0,385 0,651 0,270 -0,141 0,109 0,107 GRATIFYING (G) Fun 0,114 0,402 0,069 0,610 0,317 0,014 -0,024 Gratifying 0,254 0,162 0,523 0,624 -0,023 0,177 -0,055 Stimulating 0,187 0,150 0,190 0,756 0,231 0,202 -0,082 Educational 0,543 0,013 0,276 0,674 0,085 -0,112 0,017 Suggestive 0,007 0,151 0,287 0,702 0,094 0,154 0,213 LOCALTY (L) Traditional 0,086 0,070 0,120 0,037 0,823 -0,040 0,154 Niche 0,040 -0,184 -0,113 0,271 0,671 0,126 0,067 PLEASANTNESS (P) Pleasant 0,173 0,356 0,182 0,257 0,104 0,738 0,123 Good 0,432 0,079 0,456 0,228 0,030 0,560 0,081 Component 7 (C7) Seasonal 0,312 -0,090 0,342 0,233 0,259 0,056 -0,451 Nostalgic -0,031 0,062 0,040 0,013 0,269 0,069 0,783 Cronbach's α 0,936 0,9 0,905 0,879 P value 0,479 0,607 -0,151

Furthermore, convenience (C) principal component (12% variance) is assessed with 8 items expressing both economic convenience (cheap), SFSCs’ perceived ease linked to time saving and life simplifying issues (simple, easy, fast, convenient, relaxing), and finally repurchase frequencies and consumer loyalty (frequent, usual). Finally, the third principal component LD (useful; local; aware; important; necessary) is

47

closely linked to reflexive consumerism, testifying the post-modern consumer’s perceived importance in local development. As a matter of fact, encouraging and supporting short circuits (i.e. direct selling or farmers’ markets), consumers actively participate in traditional niche markets’ value creation and in local products’ valorization, getting back some personal gratification.

CONCLUSIONS

This work presents a preliminary study that investigates determinants of post-modern consumers’ attitude towards purchasing in SFSCs, instead of mainstream markets. Salient attitudinal variables were elicited by means of direct interviews, during a pre-survey built on a TPB pilot questionnaire. A content analysis with a deductive approach explored all the attitudinal variables self-revealed by 60 italian university students in December 2014. In addition, a semantic differential has been edited on these variables and then a PCA condensed interviewees’ responses from the original 36 items into 7 principal components. In this way, sustainability, convenience and local development are found to be the most significant predictors of SFSCs’ shopping intention, since they explain up to 57,4% of total variance. These components are assessed by multiple variables expressing different aspects and relevant information orienting SFSCs’ shopping attitudes of post-modern consumer. Additionally, we found other components (gratifying, localty, pleasantness) that

48

stress some additional information about the attitude under investigation. The identification of the main attitudinal determinants is only a preliminary stage in the study of the intention to purchase in SFSCs; moreover, considering multiple-dimensional complex points such sustainability, convenience and local development, this work embodies an articulate approach that requires some deep further studies of consumer behavior. Since the intention under investigation can be considered an antecedent of behavior, it has many policy implications: for example, the choice of appropriate actions to promote SFSCs, as tailoring communication and marketing strategies among both consumers and farmers. Based on our initial results, further research will survey a more expanded consumers’ sample in order to investigate other TPB variables underlying consumers’ intention and behavior towards shopping in SFSCs, such as subjective norms and perceived control behavior.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 50, pg.179-211.

Ajzen, I. (2006). Constructing a TPB Questionnaire, Conceptual

and Methodological Considerations. Retrieved from: