The Challenges of

Implementing Open Innovation

Doctoral Dissertation presented by:

Chiara Eleonora De Marco

To

The Class of Social Sciences

For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of

PhD in Management: Innovation, Sustainability and Health care

Curriculum: Innovation Management

A.Y. 2016-2017

Supervisor: Alberto Di Minin

The Challenges of

Implementing Open Innovation

Chiara Eleonora De Marco

Supervisor

!Co-Supervisor

!2

Acknowledgments

There couldn’t be topic that would have fit my Ph.D. dissertation more than the challenges. In the last three years, or three months, this Ph.D. pulled all the possible strings I couldn’t imagine I had, but I know I tried to face all as I have been thought to do. Though, saying that I survived the Ph.D. is not mine to say now. In the meanwhile, I need to thank for all the things and people that walked with me through these days.

First of all, let me thank Alberto, Andrea and Henry. Each of them, in his own ways, supervised me over the Ph.D. path and made me understand which kind of person I want to be and which kind I don’t. Though, I own Alberto a special thank for his subtle ways of pushing me over my limits and making me realize that there’s always an alternative option and, most of the time, making it

something good is only up to your decision of catching it.

I need to express my gratefulness for the sympathetic gazes from Arianna and the heartening smiles from Maria Giulia: they encouraged and appeased me infinite times. Thanks to Antonia, Stefania, Nadia and the other people at the Institute of Management: no Ph.D. student would survive this world without their endless administrative (and not) support. Thanks, infinite thanks to Claudia, for her special touch in being always present, helpful, understanding and discrete as no-one could ever do, even if a bit too nervous sometimes (!)… Thank you for the empathy in Terzani, from Alliata, and much more beyond there. A special thanks to Para, his special counseling for surviving the Ph.D. … I know I wasn’t able to seize all your hints, but I always gives you credit for your advices! I still own you four or five beers and I promise I’ll pay my dues!

Thanks to my ‘life-mate’ Cristina, for her schizophrenia and for being so different from me. Your guidance across Pavitt, trajectories, and much more has been priceless. Your overwhelming heart and my silent diplomacy pulled our differences to achieve the maximum benefits of a co-working friendship, we always had a full pipeline and I know that it will be even more in the coming future. Thanks to Hérica for the care and support I didn’t even know I needed, for all the enlightening brainstorming and the listening. You’re the richest heart from a “poor country” I ever met! Thanks to Martina for all the unbearable situations we went through together. I know I’m writing acknowledgements “already”, but we resisted all of this together and I won’t feel like I’m done until you’ll be too… so… hurry up, vecchia!

Thanks to Irene for being a perfect ‘Special Needs Teacher’, ignoring my stupid questions and comments. You finally gave me the feelings of being able to read those impossible tables, and I wouldn’t have been writing these pages without your patience and help! Thanks to Giulio and Matteo for contributing on the work that is now part of my dissertation, but will be our work for the interesting months to come. Thanks to Elena for the Santa Clara talks over a drink, I wish you save those moments in your heart.

Thanks to Fabrizio and his eye-opening suggestions, I think I held on quite well, but I know you’re going to tell me ‘tieni botta’ many times again! Thanks to the entire InnoGroup: Nicola, Valentina,

3 Deepa, Shahab and his fresh-pistachio kindness, the affiliated Pirri, Giada and the TTO people. Thanks to all the Ph.D. students and colleagues: Jonathan, Giuseppe, Silvia, Stefania, Ester (and the little Petra!) Chiara2, Shanshan, Emmanuel, SGM and all the others. Each one of you offered

something peculiar to this three years and I know I’ll always have someone around the world to have a beer with!

I need to thank Giulio for his endless support in my beloved DC and for being a trustful friend even more than a supervisor, and to my Berkeley colleagues and friends for making the scary California nicer to me. And thanks to Mauri for reminding me that special persons still exist and I’m still able to recognize them… sometimes!

Endless thanks to Maral. I know that finding a true friend at work is something so rare that I still struggle in believing that’s true. Thanks for being so emotional and letting me be with you as I could during all these years. Thanks for the great talks always, though you know I appreciated the jet-lagged ones more than anything! Thanks for making the working together so funny and productive any time and in any ways, thanks for being my hidden life and not-life supervisor. Thanks for being a friend and nothing else, always…. Did I say thanks?!

And now…. Let’s switch to the people that somehow have always been there and always will be. Thanks to Reda and Nina and Mari, for all the support they never spared for me, for their being always on the right page even understanding nothing of where I was and what I’ve been doing in the last three years. Thanks for the visits and travels wherever… but most of all thanks for making me feel home every time we’re together or with every 7.40p.m. break.

Thanks to the Avverbio for the human-alarm he became, the only alarm I will ever tolerate, for the coffee-making and for being such a good person. Thank you for showing up in my life again while I was writing a dissertation. Be advised: that’s my last one, but I know you’ll stay wherever we’ll go. Thanks to my family, for reminding me that sometimes it’s not worthy to worry. Bigger or smaller it will always be the only thing that really matters. Thanks to my mum and dad, to Erika and Peppe. Thank you for the example you gave me in working hard, committing fully and engaging with enthusiasm, putting the maximum possible effort in doing everything. But most of all, thanks for giving me the right perspectives, minimize and prioritize the right things. Thank you for being in me in everything I do, for being my inspiration and my models, for making me feel home in your eyes. And, if there’s anything left to say thanks for, then thanks to Gianluca for being so brazen, making challenges awesome and dreadful, much more than I could imagine.

Despite of everything I managed to get there and write these acknowledgements. And now that everything is in my own hands, it feels ‘fantastic’.

4

Contents

Acknowledgments... 2 List of Table ... 8 List of Figures ... 9 List of Acronyms ... 10 Introduction ... 11The Concept of Open Innovation ... 11

OI as a Phenomenon-Driven Research ... 12

Scope of the Dissertation ... 13

Structure of the Dissertation ... 14

Chapter I - Clarifying the Challenges of Open Innovation. A Systematic Literature Review and a Taxonomy. ... 14

Chapter II - Implementing Open Innovation: a High Hurdles? ... 15

Chapter III - Money, Money, Money… Is EU Innovation Policy Addressing the Right Issues when Targeting SMEs? ... 16

References ... 18

Chapter I - Clarifying the Challenges of Open Innovation. A Systematic Literature Review and a Taxonomy. ... 20

I-1. Introduction ... 21

I-2. Background ... 22

I-3. Methodology ... 24

I-3.1. Review Design ... 24

I-3.2. Data Analysis ... 27

I-3.3. Data Description ... 28

I-4. Findings: Internal and External Challenges of the OI ... 30

5

I-4.2. External Challenges... 33

I-5. Systematization of the OI Challenges in LEs and SMEs ... 37

I-6. Conclusions ... 40

I-6.1. Systematization of the Challenges of OI ... 41

I-6.2. Research Agenda ... 41

I-6.3. Managerial Implication of this study ... 42

I-6.4. Limitations of the study... 43

I-References ... 44

Chapter II - Implementing Open Innovation: a High Hurdles? ... 50

II-1 Introduction ... 51

II-2 Background ... 52

II-2.1 The Taxonomy of OI Challenges ... 53

II-3 Research Methodology ... 56

II-3.1 Research design ... 56

II-3.2 Data collection ... 56

II-3.3 Data analysis ... 57

II-4 Results ... 62

II-4.2 Challenges of LEs ... 63

II-4.3 Challenges of SMEs ... 68

II-5 Discussion and Conclusions ... 73

II-5.1 Validation of the OI Challenges Taxonomy ... 73

II-5.2 Limitations and future research ... 78

II-References ... 79

II-Annex ... 83

Chapter III - Open Innovation Challeges in SMEs as a target for EU Innovation Policy ... 95

6

III-2 Background: SMEs’ starring role in European Union... 97

III-2.1 Government support of small firms in the context of SMEs Growth debate ... 98

III-2.2 Evolution of EU policy support to SMEs ... 99

III-2.3 Challenges of OI implementation in SMEs ... 102

III-2.4 SMEs in the Digital Sector ... 105

III-2.5 Scope of the study... 106

III-3 Methodology ... 106

III-3.1 Research Design and Data Sources ... 106

III-3.2 Company Selection ... 107

III-3.3 Database Construction ... 107

III-3.4 Operationalization of the OI Challenges ... 108

III-3.5 Data Analysis ... 108

III-4 Results ... 111

III-4.1 Internal Assets Protection ... 111

III-4.2 Management of External Relations ... 113

III-4.3 SMEs Engaged in Over-Searching ... 114

III-4.4 SMEs Engaged in Business Model Innovation ... 115

III-4.5 Correlation between the markers ... 116

III-5 Discussion ... 118

III-5.1 Limitations and Future Research ... 121

III-6 Conclusions ... 122 III-References ... 124 III-Annex 1... 129 III-Annex 2... 130 Conclusions ... 136 Key Findings ... 136

7

The Taxonomy of OI Challenges ... 137

OI Challenges in LEs and SMEs ... 139

SMEs OI Challenges as a Target for EU Innovation Policy ... 141

Contributions of the Dissertation ... 143

Conceptualization of the Challenges of Implementing OI ... 144

Methodological contribution ... 145

Policy Implications ... 145

8

List of Table

TABLE LABLE PAGE

I-1 Categories included in the search on Web of Science 26

I-2 Levels of Analysis of the Research 28

I-3 The taxonomy of challenges of OI in Private R&D and Innovation in extant literature 30

I-4 The challenges of OI in LEs and SMEs 38

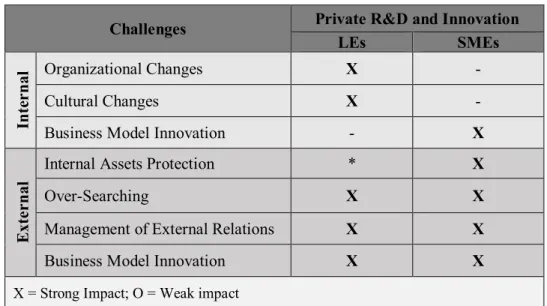

II-1 The challenges of Open Innovation in extant literature 53

II-2 The challenges of OI in LEs and SMEs 55

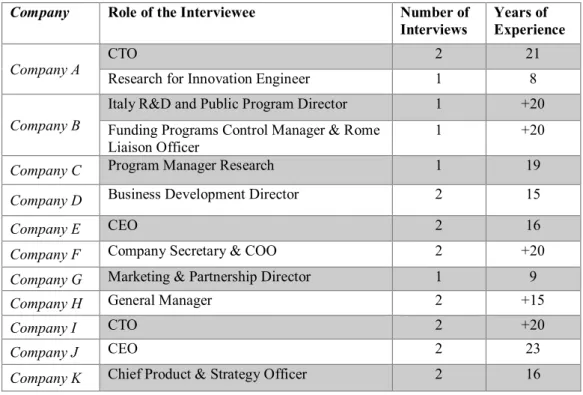

II-3 The Interviewees 57

II-4 Basic company-level data 59

II-5 Motivations for engaging in OI and Modes of OI Implementation 60

II-6 Results Overview 62

II-7A LEs OI Challenges – Results and Key Quotes 83

II-8A SMEs OI challenges – Results and Key Quotes 86

III-1 The three pillars of Horizon 2020 101

III-2 Operationalization of Markers 108

III-3 Descriptive characteristics of the sample 110

III-4 Baseline characteristics for SMEs engaged in Internal Assets Protection (M1) 112

III-5 Baseline characteristics for SMEs engaged in Management of External Relationship

(M2)

113

III-6 Baseline characteristics for SMEs engaged in Over-Searching (M3) 114

III-7 Baseline characteristics for SMEs engaged in Business Model Innovation (M4) 116

III-8 Markers correlations matrix 117

III-9 Associations between the Markers 117

III-10A The three phases of the SME Instrument 129

III-11A Sample Selection Process 130

III-12A Technology variables 131

III-13A Events variables 132

III-14A List of Events Labels 133

III-15A Harmonization of Events Labels 134

III-16A People variables 135

9

List of Figures

FIG. LABLE PAGE

I-1 PRISMA flowchart: process for identifying and retaining studies 27

I-2 Source of the Studies 28

I-3 Year of publication of studies included in the sample 29 I-4 Top Journals per number of papers published referring to OI challenges 29

10

List of Acronyms

ACRONYM ABBREVIATED EXPRESSION

AMADEUS BVD Amadeus Bureau van Dijk

B.A. Bachelor

EASME Executive Agency for Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises EBIT Earnings Before Interest and Taxes

EC European Commission

EU European Union

FP Framework Program

H2020 Horizon 2020

HR Human Resource

ICT Information and Communication Technology IP Intellectual Property

IPR Intellectual Property Right

LE Large Enterprise

M.A. Master of Arts

M.Sc. Master of Science

MBA Master of Business and Administration

NIH Not Invented Here

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OI Open Innovation

OIS Open Innovation Strategy PDR Phenomenon-Driven Research

Ph.D. Philosophiae Doctor

PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses R&D Research and Development

RSO Research Spin-Off

S&T Science and Technology

SE Standard Error

SME Small- and Medium-sized Enterprise

SMEi SME Instrument

SoE Seal of Excellence

TDR Theory-Driven Research

11

Introduction

The Concept of Open Innovation

The concept of Open Innovation (OI) appeared for the first time in the book of Henry Chesbrough in 2003. It was described as a process of distributed innovation across different actors, based on the purposive management of knowledge in-flows and out-flows across organizations (Chesbrough 2003a).

Several factors favored the flourishment of OI, and all of them refer to the phenomenon of globalization. The higher availability and diffusion of knowledge and high-skilled workers, enabled by their enhanced mobility along with the increased availability of venture capital, eased the pursuit of OI practices coming up beside and, often, substituting closed innovation models (Chesbrough 2003a; Elmquist et al. 2009; Sofka & Grimpe 2009). With respect to the traditional closed innovation model, the pursuit of OI reduces the costs and the level of uncertainty of internal R&D projects, and allows the access to a wider range of resources with which a single organization cannot be endowed (i.e. infrastructures, facilities, equipment, technologies, knowledge, human resources). The whole concept of OI is based on a logic of abundancy and distribution of knowledge that characterizes the modern economy, a globalized and knowledge-based economy in which the closed innovation paradigm has been overturned (Chesbrough 2015a). As a result, large corporations lost the monopoly they had on knowledge and innovation, while small companies resulted to be even more innovative than their larger competitors were, and able to dedicate their entire R&D activity to specific segments of the innovation process. In an open paradigm of innovation, indeed, the innovation process is fragmented and distributed across actors and loci that go beyond the boundaries of not only single R&D units, but also entire organizations. Scholars and practitioners showed high interest for the new paradigm of innovation and demonstrated that breaching organizational silos and boundaries provides benefits to innovation processes. Small- and medium-sized enterprises, spin-offs, university labs, start-ups, play a role on the stage of innovation, specializing on small fractions of a complementary innovation process in which they collaborate with other actors in order to achieve mutual benefits from the outcome of their innovation processes (De Marco & Di Minin 2017).

12 Scholars of innovation management dedicated a lot of attention to the phenomenon of OI: the topic became extremely popular to the extent that Chesbroughachieved almost 54.5K citation on Google Scholar after coining the expression. Literature has explored several aspects of the phenomenon. The addressed topics range from OI definition (Chesbrough & Bogers 2014; West & Bogers 2017), to modes of implementation (Gassmann & Enkel 2004), from its application in large corporations (Mortara & Minshall 2011) and, most recently, in the small business sector (Vanhaverbeke et al. 2012), to the actors involved in the OI processes (Ahn et al. 2017; Cheng & Chesbrough 2017). In the last few years, researchers expanded their interests to the potential application of OI concepts in the public sector (de Jong et al. 2008; Chesbrough & Vanhaverbeke 2011; Mergel & Desouza 2013). In addition, interest for OI has been shown even from policy makers that were inspired by the concept of openness and accordingly designed their actions (Obama 2009; Moedas 2015).

OI as a Phenomenon-Driven Research

Some scholars criticized the newness of the OI concept (Trott & Hartmann 2009) and are reluctant to define it as theory. These criticisms find some grounds in modern innovation management literature. Scholars addressed many of the aspects related to the permeability of boundaries in firms that overcome them in order to conduct their business activity effectively. Relying on partnerships, alliances and collaboration with different industrial partners and/or their own users and customers (von Hippel 1988), such as research contract, technology acquisitions and licensing activities (Teece 1986) is not new for organizations, nor for researchers.

OI did not propose itself as a theory, and scholars described it is a ‘complex, multi-dimensional

phenomenon which compels us to combine different perspectives into a broader, dynamic (or stepwise) framework” (Vanhaverbeke & Cloodt 2014, p.273). Therefore, current research on OI can be defined

as a Phenomenon-Driven Research (PDR) in contrast to the more diffused and traditional Theory-Driven Research (TDR). The PDR draws on and combines theories to provide comprehensive explanation of new phenomena or alternative perspectives on already known ones. While the goal of TDR follows cumulative patterns, providing incremental contributions to existing theories or creating new ones, PDR aims at offering additional knowledge and facilitate the understanding of a phenomenon that existing theories cannot exhaustively explain (Eisenhardt & Graebner 2007). Therefore, the contribution of the PDR can also results in the theory enhancement or the generation of new concepts and theory that have been derived inductively and/or deductively from the exploration of the phenomenon (von Krogh et al. 2012). Scholars have, indeed, recalled the value of the PDR as an alternative to the TDR to overcome the current ‘theory obsession’ that is limiting the opportunities

13 for interesting advances in the social science and organizational research (Schwarz & Stensaker 2014). Nonetheless, the PDR does not exclude the foundation of theory: PDR can be complementary to theory building and testing, but would never substitute them (von Krogh et al. 2012; Schwarz & Stensaker 2014).

The body of knowledge concerning OI has been developed starting from the observation of the reality (Chesbrough 2003b). OI scholars recognized the existence of a theoretical deficit in the debate on OI and called for further research aimed at filling this gap, arguing that the extant management theories could provide an adequate framework to the OI phenomena only if combined together (Vanhaverbeke & Cloodt 2014). The authors highlighted the connections among OI and some theories of the firms (i.e. transaction cost economics, resource-based view, resource-dependence theory, relational view, and real option theory) and some theoretical concepts (i.e. absorptive capacity and dynamic capabilities). Nonetheless, OI still seems to be a topic addressed through a PDR approach.

For these reasons, the conceptual power of OI cannot be underestimate. The OI paradigm provides a new perspective towards the phenomena analyzed through different theoretical lenses (Mortara et al. 2010). It is an umbrella-concepts that is able to gather multiple, diversified actions that organizations conduct pursuing specific goals. Through the concept of OI, all these phenomena can be observed at a glance and at the same time, in order to have a broad and comprehensive understanding of the overall strategy that organizations put into practice in pursuing competitive advantage.

Scope of the Dissertation

The interest for OI has been developed focusing on the benefits and advantages that organizations can achieve breaching their boundaries and diffusing their processes of innovation. Indeed, companies achieved positive outcomes from OI Strategies (OISs) implemented in a variety of industry, and right after the launch of the OI concept, researchers enthusiastically explored and reported these successes, making the OI become a hot topic of the innovation management literature (Mortara et al. 2010). The scholarship provided evidence of the OI effectiveness and developed the debate on how to harness OI to maximize the outcomes of open strategies.

However, the innovation itself is a risky and challenging activity that requires companies to make investments whose return is completely uncertain (Pisano 2015). Undoubtedly, when these investments do not concern the single organization, but involves a plurality of actors and loci, as it happens in a diffused process of innovation as the OI one (Spithoven et al. 2013), the levels of uncertainty and risk are even higher. Scholars reported the complexity of the implementation of open

14 strategies, describing OI as a multidimensional and context-related phenomenon (Huizingh 2011). However, despite the researcher dedicated a lot of attention to the OI practices and its outcomes, they generally neglected to explore at what costs these outcomes are achieved (Cassiman & Valentini 2016), leaving the challenges1 of implementing open and collaborative innovation strategies still an

understudied topic in the literature of OI.

Adopting the PDR approach, the scope of this dissertation is to counterbalance the debate on OI and shed light on the aspects that have been underexplored in the first fifteen years of history of the concept: the downsides of openness. Recent research agendas emphasized the lack of research on the challenges involved in the implementation of open approaches to innovation (Chesbrough 2015b; Dahlander & Gann 2010; Spithoven et al. 2013; Lenz et al. 2016). Therefore, within the context of the OI phenomenon, this research aims at providing an answer to the general question: which are the

challenges that companies face in implementing OI?

Structure of the Dissertation

In order to answer the general research question, both theoretical and empirical perspectives have been adopted and developed on three different contextual levels of analysis: conceptualization, practice and policy. Per each of these levels, specific sub-research questions have been formulated and addressed in three stand-alone academic papers, corresponding to the three main chapters of this dissertation, through different methodologies. The following paragraphs presents the structure of the dissertation, providing a brief overview of each paper, the research questions addressed and the methodologies applied.

Chapter I - Clarifying the Challenges of Open Innovation. A Systematic

Literature Review and a Taxonomy.

The first research paper – Chapter I – adopts a theoretical perspective to explore the topic of the challenges of implementing OI on a conceptual level of analysis. The literature on OI let emerge the complexities that firms encounter in breaching their organizational boundaries once they embrace OI. Nonetheless, previous studies mainly explored the shift from a closed to an open paradigm of innovation, concentrating on the successful outcome of the shift and the new strategy adopted. The challenges that firms face during the processes of paradigm shift and strategy implementation are generally left on the background of the studies, generating a lack of knowledge on the topic. In order

1 With the term ‘challenge’ we refer to any factor susceptible to hinder the success of the strategy, any problem rising

during the implementation of the strategy, and any obstacle to be overcame in pursuing the achievement of OI benefits (Sandberg & Aarikka-Stenroos 2014).

15 to disentangle the underexplored aspect of the OI implementation challenges, this study develops a systematic literature review with the aim of addressing two research questions:

• What challenges of implementing OI already emerge from the literature? • What should be done in order to shed light on the drawbacks of practicing OI?

The systematic literature review was conducted on 122 studies. The analysis adopted a concept-centric approach, focused on the challenges of implementing OI strategies on the level of analysis of the private R&D and innovation processes, considering two subunits of analysis: Large Enterprises (LEs) and Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). Building on Piatier’s (1984) classification of internal and external barriers to innovation, the OI challenges were systematized in an original taxonomy including two categories: internal and external challenges, whether they arise within or outside organizational boundaries, and are therefore more or less subject to the organization’s influencing power. This study offers a threefold contribution. First, it identifies and systematizes the challenges of implementing OI emerging from extant literature. Second, it proposes a research agenda to address current gaps in the OI debate, shedding light on the neglected aspect of its downsides. Third, it provides valuable managerial implications for practitioners that embrace OI.

Chapter II - Implementing Open Innovation: a High Hurdles?

The second research paper – Chapter II – adopts both theoretical and empirical perspectives to explore the topic of the challenges of implementing OI on a practical level of analysis. The paper explores the boundary situations that are potentially beneficial for a company that undertook OI but that, during the implementation of an open strategy, reveal disadvantages and drawbacks causing additional and actual difficulties to the company. The study explores the motivations of challenges and the reasons that make managing the challenges crucial focusing on LEs and SMEs. The aim is to address two research questions:

• Which are the motivations for which the challenges of implementing OI arise? • Which are the characteristics of the OI challenges in LEs and SMEs?

Building on the findings of the first paper of this dissertation, this second paper validates the OI challenges taxonomy through eleven explorative case studies on European large and small- and medium-sized enterprises that embraced OI. The analysis applies an original interpretation framework of the process of OIS implementation including three phases: negotiation, implementation, and exploitation of the results. The study results validate the taxonomy of internal and internal challenges

16 of OI and provide a complete description of the characteristic of challenges, highlighting the differences in the reasons for arising and peculiarities presented in firms with different dimensions. The paper offers valuable implications for both scholars and practitioners of OI. It enhances current knowledge on a neglected aspect of the phenomenon of OI and provides the managers of both LEs and SMEs that undertake OI with a comprehensive awareness of the typologies of challenges that may hide behind the benefits of opening up the innovation process.

Chapter III – Open Innovation Challenges in SMEs as a target for EU

Innovation Policy

The third research paper – Chapter III – of this dissertation, adopts both theoretical and empirical perspectives to explore the topic of the challenges of implementing OI and shift the analysis to the policy level. The paper explores the phenomenon of the OI challenges in the context of the European Union (EU) public policies supporting small business innovation and R&D. In the current scenario, policies supporting the small business sector tend to focus mainly on reducing fiscal and administrative burdens and the filling the ‘equity gap’ through the provision of financial support. Nonetheless, previous literature showed that, to obviate the problems related to their lack of resources, SMEs engage in open and collaborative innovation strategies (Hossain & Kauranen 2016), facing specific challenges that are not limited to financial issues. This paper aims at addressing the following research question: • Which are the issues that a public policy targeting innovation and R&D in the small business

sector should address, going beyond the ‘equity gap’ problem?

This paper build on the findings of the previous two studies included in this dissertation, considering the relevance of external challenges of OI for SMEs. In order to answer the research question, it proposes an original methodology through which SMEs OI challenges can be operationalized and their presence can be signaled. The study tests this methodology on a selected sample of 209 ‘EU innovation champions’ operating in the digital sector, awarded public funding by the SME Instrument, the most recent tool introduced by the eight EU Framework Program on Research and Innovation, Horizon 2020. The paper provides both managerial and policy implications. To practitioners that embrace OI, this paper offers insights on how their companies’ characteristics might associate to the rising of the OI challenges. To policy-makers, this study offers evidence that even the ‘EU innovation champions’ present challenges that should be considered and addressed in a public policy targeting small business innovation and research.

17 All the three stand-alone papers aim at providing an answer to the general question of which are the challenges that companies face in implementing OI. The answer to this question is offered in the final chapter of the dissertation, which draws the conclusion, highlights the contributions, and identifies the limitations of this study offering proposals for future research.

18

References

Ahn, J.M., Minshall, T. & Mortara, L., 2017. Understanding the human side of openness: the fit between open innovation modes and CEO characteristics. R&D Management, pp.1–14.

Cassiman, B. & Valentini, G., 2016. Open Innovation: are Inbound and Outbound Knowledge Flows really Complementary? Strategic Management Journal, 37, pp.1034–1046.

Cheng, J. & Chesbrough, H.W., 2017. A Profile of Open Innovation Managers in Multinational Companies. Chesbrough, H.W., 2015a. From Open Science to Open Innovation. Science Business Publishing.

Chesbrough, H.W., 2003a. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from

Technology., Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Chesbrough, H.W., 2015b. Opening Session Speech. In 2nd Annual World Open Innovation Conference. Santa Clara, California.

Chesbrough, H.W., 2003b. The Era of Open Innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review, 44(3), pp.34–41. Available at: http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2316408.

Chesbrough, H.W. & Bogers, M., 2014. Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation. In H. W. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, & J. West, eds. New Frontiers in

Open Innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–38.

Chesbrough, H.W. & Vanhaverbeke, W., 2011. Open Innovation and Public Policy in Europe. Science - Business Publishing Ltd.

Dahlander, L. & Gann, D.M., 2010. How open is innovation? Research Policy, 39(6), pp.699–709. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.013.

Eisenhardt, K.M. & Graebner, M.E., 2007. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges.

Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), pp.25–32.

Elmquist, M., Fredberg, T. & Ollila, S., 2009. Exploring the field of open innovation. European Journal of

Innovation Management, 12(3), pp.326–345. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14601060910974219.

Gassmann, O. & Enkel, E., 2004. Towards a theory of open innovation: three core process archetypes. R&D

management conference, pp.1–18. Available at: http://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/export/DL/20417.pdf.

von Hippel, E., 1988. The sources of innovation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hossain, M. & Kauranen, I., 2016. Open innovation in SMEs : a systematic literature review. Journal of

Strategy and Management, 9(1), pp.58–73.

Huizingh, E.K.R.E., 2011. Open innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. Technovation, 31(1), pp.2–9. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2010.10.002.

de Jong, J.P.J. et al., 2008. Policies for Open Innovation: Theory, framework and cases, Helsinki. Available at: http://www.eurosfaire.prd.fr/7pc/doc/1246020063_oipaf_final_report_2008.pdf.

von Krogh, G., Rossi-Lamastra, C. & Haefliger, S., 2012. Phenomenon-based research in management and organisation science: When is it rigorous and does it matter? Long Range Planning, 45(4), pp.277–298. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2012.05.001.

19

Journal of Innovation Management, 20(7), p.1650063–01/26. Available at:

http://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/S1363919616500638.

De Marco, C.E. & Di Minin, A., 2017. Tra Open Science e Open Innovation: costruire un ponte per la valorizzazione di Scienza e Tecnologia. Paradoxa, XI(1), pp.121–132.

Mergel, I. & Desouza, K., 2013. Implementing Open Innovation in the Public Sector: The Case of Challenge. gov. Public Administration Review, 73(6), pp.882–890. Available at:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/puar.12141/full.

Moedas, C. Open Innovation , Open Science , Open to the World. June 2015.

Mortara, L. et al., 2010. Implementing open innovation: cultural issues. International Journal of

Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 11(4), p.369. Available at:

http://search.proquest.com/docview/845180052?accountid=39039.

Mortara, L. & Minshall, T., 2011. How do large multinational companies implement open innovation?

Technovation, 31(10–11), pp.586–597. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2011.05.002. Obama, B. Transparency and open government.January, 2009.

Piatier, A., 1984. Barriers to Innovation F. Pinter, ed., London, Dover NH.

Pisano, G.P., 2015. You Need an Innovation Strategy the Big Idea. Harvard Business Review, 93(June), pp.44–54.

Sandberg, B. & Aarikka-Stenroos, L., 2014. What makes it so difficult? A systematic review on barriers to radical innovation. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(8), pp.1293–1305. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.08.003.

Schwarz, G. & Stensaker, I., 2014. Time to Take Off the Theoretical Straightjacket and (Re-)Introduce Phenomenon-Driven Research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(4), pp.478–501. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0021886314549919.

Sofka, W. & Grimpe, C., 2009. Specialized Search and Innovation Performance – Evidence Across Europe, Available at: ftp://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/dp/dp09016.pdf.

Spithoven, A., Vanhaverbeke, W. & Roijakkers, N., 2013. Open innovation practices in SMEs and large enterprises. Small Business Economics, 41(3), pp.537–562.

Teece, D.J., 1986. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy, 15(6), pp.285–305.

Trott, P. & Hartmann, D., 2009. Why “Open Innovation” is old wine in new bottles. International Journal of

Innovation Management (ijim), 13(4), pp.715–736.

Vanhaverbeke, W. & Cloodt, M., 2014. Theories of the Firm and Open Innovation. In H. W. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, & J. West, eds. New Frontiers in Open Innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 256–278.

Vanhaverbeke, W., Vermeersch, I. & Zutter, S. De, 2012. Open innovation in SMEs: How can small

companies and start-ups benefit from open innovation strategies?, Available at:

http://conference.ispim.org/files/OI_in_SMEs.pdf.

West, J. & Bogers, M., 2017. Open Innovation : Current Status and Research Opportunities. Innovation:

20

Chapter I

Clarifying the Challenges of Open Innovation.

A Systematic Literature Review and a Taxonomy.

Abstract: Going beyond the popular effectiveness argument of the OI paradigm, this study disentangles a

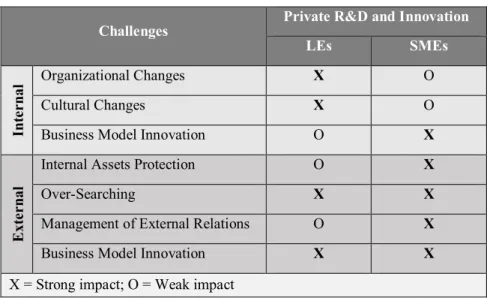

neglected aspect of OI: the challenges embedded in its implementation. We perform a systematic literature review in order to provide a clear overview of the state-of-the-art of academic scholarship on OI, and systematize our findings in two categories: internal and external challenges, whether they arise within or outside organizational boundaries, and are therefore more or less subject to the organization’s influencing power. Within their organizational boundaries, large companies struggle in implementing organizational and cultural changes along with OI strategies, while SMEs are more concerned with the challenge of innovating their business models. Outside their organizational boundaries, the internal assets protection, over-searching, management of the external relations and business model innovation are the most diffused challenges for both large and small- and medium-sized companies. The contribution of this study is threefold. First, we identify and systematize the challenges of implementing OI emerging from extant literature. Second, we propose a research agenda to address current gaps in the debate on OI, shedding light on the neglected aspect of its downsides. Third, we provide valuable managerial implications for practitioners that embrace OI in their activities.

Keywords: Open Innovation, Systematic Literature Review, Challenges, Taxonomy, Large Enterprises, SMEs.

Note to the reader: Earlier versions of this paper have been presented during the 3rd World Open Innovation Conference

2016 and during internal Open Innovation Seminars at the Haas School of Business of the University of California, Berkeley.

We thanks the anonymous reviewers of the WOIC 2016 and the useful suggestions and comments on the first drafts of this work received by colleagues participating to the Haas OI Seminars: Henry Chesbrough, Frédéric Le Roy, Marcus Holgersson, Annika Lorenz, Mei Liang, Dongui Meng, Denis Schuler, Billy Chen-yu Wang, Ivanka Visnjic, Rodrigo Cortopassi Lobo, Maria Carkovic, Solomon Darwin.

21

I-1. Introduction

The Open Innovation (OI) paradigm (Chesbrough 2003a) recently entered the second decade of its life but it had already became one of the hottest topic in innovation management, due to the growing interest received from both scholars and practitioners (Giannopoulou, Yström, & Ollila, 2011). Academics have been contributing to the literature on OI from several perspectives. First, high attention has been paid to the identification of a notion of OI and to the investigation of the phenomena falling under the definition of OI. The definition adopted in this work is the one provided by Chesbrough in his first book (2003a:xiv) considering OI “a paradigm that assumes that firms can and

should use external ideas as well as internal ideas, and internal and external paths to market, as the firms look to advance their technology. Open Innovation combines internal and external ideas into architectures and systems whose requirements are defined by a business model”. Second, academic

research raised multiple arguments in the debate on OI, including issues that range from the inter-organizational level – the most widely explored – to the inter-organizational and individual ones, on which research is still scant (West et al. 2006; Salter et al. 2014). Researchers also focused on the modes of implementation of open strategies and their overlaps with business model innovation and appropriation strategies (Elmquist & Le Masson 2009; Salter et al. 2014; Granstrand & Holgersson 2013).

The effectiveness arguments for OI has been the main focus of both academics and practitioners. Scholars largely demonstrated that this paradigm offers the great opportunity of redefying the role of research in corporate R&D. They argue that OI allows wider access to knowledge, the creation of more differentiated products that better meet users’ preferences, larger networks, connection, and the integration of knowledge and technological assets that accelerate the innovation process (Chesbrough 2003a, 2006b; Chesbrough & Crowther 2006; Gassmann 2006; Almirall & Casadesus-Masanell 2010).

Nonetheless, innovation is a risky activity, intrinsically characterized by the outcome uncertainties entailed in a process that aims at producing novelty, in discontinuity and change with the previous state of the art (Jalonen 2012). This unpredictability is even greater when the innovation process does not concern a single organization, as it happens in a closed innovation process, but involves a multitude of actors and loci of innovation (Abu El-Ella et al. 2016), as encompassed in the paradigm of OI (Spithoven et al. 2013). For these reasons, the starting point of this study assumes, as some scholars acknowledged (Goduscheit 2014), that embracing an open approach to innovation implicates the rising of potentially problematic situations that the acting organization need to face and overcome in order to gain the advantages promised by OI itself. Up to now, scholars neglected to explore the downsides

22 of implementing open innovation strategies (OISs). Therefore, the goal of this study is to shed light on these aspects.

We perform a systematic review of the extant literature with the aim of providing a clear overview of the scholarship on the downsides of OI. We identify and systematize the challenges that companies encounter in the implementation of innovation strategies once the open approach has been already adopted. We then systematize the identified challenges along two categories: internal challenges and external challenges of OI, considering whether they arise within or beyond organizational boundaries and the intensity of the influential power that companies can exert on them. For each category, we further identify the peculiarities of challenges of OI implementation in large and small- and medium-sized enterprises.

The paper is structured as follows: after the background section, we introduce the methodology applied in the process of systematically reviewing the literature, including both the search strategies and the analysis of the data. In section I-4 we report our findings and in section I-5 we discuss a classification of the challenges of implementing OI. In section 6, we draw our conclusions and present our propositions for a future research agenda.

I-2. Background

Chesbrough (2003a; 2003b) identified several factors that led to the shift from a closed to an open innovation paradigm. These factors relates to globalization, its effect on the mobility and availability of skilled human capital, and the diffusion of ICTs, along with an enhanced venture capital market (Chesbrough 2003b; Elmquist et al. 2009; Sofka & Grimpe 2009). All these elements, combined with a shortened time to market for many products and services and a subsequent increased competitiveness (Chesbrough 2003c), undermined the closed innovation model, in which companies could achieve competitive advantages only relying on internal R&D investments and proprietary assets, protecting internally developed Intellectual Property (IP) and getting to the market before their competitors.

Furthermore, the spreading of globalization effects enabled the rising of open science: due to the diffusion of ICTs and the Internet in the last decade of 20th century, knowledge has increasingly

become widely distributed, easier to access and less expensive than in the past (De Marco & Di Minin 2017). All these reasons led to another shift concerning the locus of innovation, strongly reducing the distance among the actors of the innovation process. The traditional R&D process, centrally conducted within single organizations, gives way to a diffused R&D process at the global level. While in the past

23 mostly large corporations monopolized knowledge through their rich resources and abilities in scaling up economy, the abundance and diffusion of knowledge in the last decades allowed small and medium-sized companies, research institutions, universities and public governments to play their own role in the diffused R&D (Chesbrough 2015a).

The first setting in which the OI paradigm was explored is the one of big corporation, which is also the context that first saw OI spreading (Chesbrough 2003a, 2006b; Christensen, Olesen, & Kjaer, 2005; Spithoven, Vanhaverbeke, & Roijakkers 2013). Only more recently academic interest has been shifting on the small and medium-sized enterprises and their practices of applying OI (Laursen & Salter 2006; Bianchi et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2010; Marullo et al. forthcoming).

Since the appearance of the OI concept (Chesbrough 2003a), academic scholarship has been exploring the benefits of the OI paradigm and has widely demonstrated its effectiveness. The adoption of open approaches reduces the costs of innovation while spreading the risks connected to innovation activities among several actors (partners, suppliers, users, etc.); allows companies to access a wider external knowledge base and an increased number of external innovation assets through the interaction with strategic partners. As a result, OI accelerates the time to market, increases the efficiency of R&D processes and improves productivity and adaptability to customers’ needs and demands (Gassmann & Enkel 2004; Huston & Sakkab 2006). The advantages of OI have increasingly encouraged large companies and multinationals to open up their R&D silos to external knowledge flows in the last decades, allowing them to reduce R&D costs and market uncertainty.

Up to now, literature widely explored the benefits and effectiveness of the OI paradigm, while neglecting the “other side of the coin”: the potential challenges embedded in opening up the innovation processes (Spithoven et al. 2013). Building on Sandberg & Aarikka-stenroos (2014), we define the challenges of implementing OI as any factor susceptible to hinder the success of the strategy, any problem rising during the implementation of the strategy, and any obstacle to be overcame in pursuing the achievement of OI benefits.

A limited understanding of the drawbacks involved in the implementation of open approaches to innovation both in large and in small and medium-sized enterprises has been emphasized by recent research agendas (Chesbrough 2015b; Dahlander & Gann 2010; Spithoven et al. 2013; Lenz et al. 2016). In particular, although it is still not clear whether and how much hard is to implement an OI strategy, it clearly implies various obstacles and complications, since it is widely portrayed as a complex, multidimensional and context-related phenomenon (Huizingh 2011). Indeed, from the

24 literature investigating the processes undergone by companies in the shift from a closed to an open approach to innovation, it is clear that the implementation of OI processes is not always straightforward (van de Vrande et al. 2009; Chesbrough & Brunswicker 2014; Lenz et al. 2016). OI implementation seems to be rather a path studded with challenges and obstacles that the organization needs to face and overcome in order to gain competitive advantage from OI. Some downsides of OI emerge from the literature cited above, but they are usually left in the background of the studies, which are generally focused on demonstrating the success of organizations pursuing OI, “forgetting to consider the costs

that lead to such output” (Cassiman & Valentini 2016, p.1045).

As a result, despite the literature on the OI is quite abundant, the knowledge concerning the phenomenon results currently unbalanced towards the effectiveness argument. The present work aims at counterbalancing the discussion and, in particular, contributing to a better understanding and upgrade of the academic debate on OI. To this purpose, we developed a systematic review of the extant literature on OI to answer two questions:

• What challenges of implementing OI already emerge from the literature?

• What should be done in order to shed light on the drawbacks of practicing OI?

The objective is threefold. First, we aim at systematizing the extant findings that concern the challenges faced by organizations adopting open approaches in their R&D and innovation process, and provide an interpretative framework creating a clear taxonomy of these challenges. Second, we intend to suggest a research agenda addressing the methodological, theoretical and empirical gaps currently existing in the debate on OI. Third, we are going to identify managerial implications that would enhance practitioners’ awareness and lead their practices avoiding and/or controlling the factors that could affect their companies.

I-3. Methodology

I-3.1. Review Design

Despite being a hot topic in the innovation management research (Giannopoulou et al. 2011), OI still lacks unified theoretical and interpretative frameworks (Gianiodis, Ellis, & Secchi, 2010). We conducted a systematic literature review in order to pave the way for a clearer and easier development of the debate on OI. More in depth, we intended to uncover the issues concerning the downsides of

25 openness, which have been neglected up to now and on which research activity should focus (Webster & Watson 2002) to make relevant knowledge advance.

This study applies ‘an explicit, rigorous, and transparent methodology’ (Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, & Kyriakidou, 2004: 582), in order to overcome potential bias related to a traditional review and increase the level of reliability of the findings (Tranfield, Denyer, & Smart, 2003). Furthermore, systematic literature review is largely considered as a valuable research methodology because of its high replicability as a complex method consisting of standardized and clear phases (de Vries, Bekkers, & Tummers, 2014).

We compiled the first version of the database for this study between April and July 2016. From July to October 2016, we started developing the in-depth analysis of the full texts and then, in June 2017 we repeated the search process on Web of Science in order to include new coming works. We obtained 24 records that were screened following the same steps we followed in the first place (see next paragraphs) and added to our sample 14 studies published in the first semester of 2017. The final number of studies analyzed account for 123 works.

I-3.1.1 Search Strategy

We applied several and complementary search strategies in order to reliably include in the study all the relevant works on the OI strategy implementation and the connected challenges.

The systematic search started with the process of identification of the keywords (Jesson, Matheson, & Lacey, 2011). We applied a Boolean logic to search strings including the words “Open Innovation”

AND “challeng* OR cost* OR problem* OR barrier* OR obstacl* OR hinder* OR hamper* OR imped* OR complicat* OR downside*”. The words selected for the search strings should have been

included in the title, abstract, and keyword of the documents. We launched the research on Web of Science2 database, considered as the most reliable and comprehensive database for the number of

academic studies included and the relevance of the scientific journal catalogued (Dahlander & Gann 2010; Hossain & Kauranen 2016).

We obtained 806 results and refined the research according to the science category, type of document, year and the language (see table I-1). We further reduced the sample by including only the documents

26 written in English, in order to avoid any language-related bias, and published after 2003, the year of publication of Chesbrough’s first book on OI. We obtained 227 results.

Tab. I-1. Categories included in the search on Web of Science

Science Categories Document Types Language

Management (181) Article (144) English (227)

Business (121) Proceedings Paper (83)

Operations Research Management Science (20) Review (3) Social Sciences Interdisciplinary (12) Book Chapter (1)

I-3.1.2. Screening and Assessment

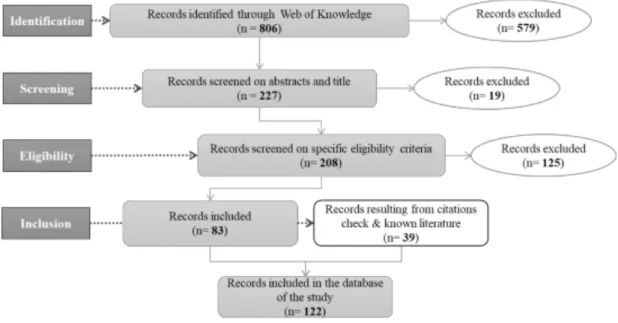

Starting from 227 records, we conducted the first round of the screening process: checking the titles and the abstracts of the works, we reduced the sample to 208 results. Nineteen records were discarded as “false positives”: they casually presented the searched combination of words or were clearly not exploring innovation processes or strategies issues.

In a second screening round, we re-assessed the records according to their relevance to the topic under analysis. We read the abstract according to the following eligibility criteria, established a priori (Liberati, Gøtzsche, & Kleijen, 2009) :

1. Type of studies. The main topic of the study should deal with OI and the implementation of open strategies in innovation processes and R&D activities.

2. Topics. The records should present in the title, abstract, and/or keywords any of the words contained in our search string. The records were included in the sample whether it seemed from the abstract that the study was referring to the implementation of OIS and it could reveal anything concerning the complexity of the process.

3. Study Design. We included in our sample primarily empirical study in order to secure an evidence-based contribution of our works (Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, & Walshe, 2005), furthermore we also included all the other research designs (questionnaire, case study, experiment, theoretical papers, etc.).

4. Data Source. We started our analysis from leading journals (Misangyi et al. 2017), supposed to include the major contribution to the literature on the field; we also included selected and high quality conference proceedings and other studies considered highly relevant for the theoretical contribution to the topics under analysis.

27 5. Publication Status. In order to ensure the quality of our review, we only selected studies provided with explicit reference to the journal of publication and/or the place in which they were presented in case of conference papers.

From the 208 records, we eliminated 125 studies that did not satisfy the above-mentioned requirements. The main exclusion reasons were that the studies were either not relevant to the debate on the topic of OI and its implementation challenges; or recalling the concept of OI in opposition to the one of closed innovation, or as a literature field to contribute to. Through reviewing the citations included in the remaining 83 records, in order to determine whether other relevant works should be included in our sample (Webster & Watson 2002), and considering our personal knowledge of the literature on OI, we added 39 more studies. The final database for our study includes 122 records. We decided not to go further in the search process because the works that we additionally screened resulted not to be adding any new concept with respect to the bulk of studies already included in the sample.

We summarize our selection process in Figure I-1 following the PRISMA approach: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (Liberati et al. 2009).

Fig. I-1. PRISMA flowchart: process for identifying and retaining studies

I-3.2. Data Analysis

We adopted a concept-centric approach, focused on the challenges of implementing OI strategies in the level of analysis of the private research and development and innovation processes (see table I-2).

28 We considered two subunits of analysis: Large Enterprises (LEs) and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs).

Tab. I-2. Levels of Analysis of the Research

Private R&D and Innovation

LEs SMEs

As Sandberg and Aarikka-Stenroos (2014) highlight, the literature on the barriers and challenges to innovation has been following Piatier’s (1984) categorization of internal and external barriers. Piatier refers to the challenges that organizations could influence and the ones that are partially or completely beyond organizations’ powers. We build on this division based on the organizational influence power, and go beyond it, considering a spatial dimension of the challenges, referring to internal challenges whether they appears within the organizational boundaries and are indeed more subject to organization’s influential powers; and external challenges whether they appears beyond organizational boundaries, being the organization less powerful in influencing them.

I-3.3. Data Description

More than 87% (106 papers) of the studies in our sample has been published in academic journal while only 13% (16 papers) was retrieved from conferences proceedings (see figure I-2).

Fig. I-2. Source of the Studies

We decided to include the conference proceedings in our sample because the debate on the OI and, particularly, the downsides of the strategy represents an emerging topic that started appearing in the scientific literature only in the last few years. Indeed, all the studies in our sample appeared between 2003 and July 2017, but the number of papers dealing with the challenges of OI sensibly increased at the end of the first decade of 2000 (see figure I-3), getting a first peak in 2010, with 19 papers involving the topic, and then again in 2016, with 20 papers. We must notice that the peak of 2016 seems to be more relevant if compared to the first one, which is the publication year of one of the R&D Management Special Issue on OI. Moreover, our research covers only the first semester of 2017, when

13%

87%

Conference Papers Journal Papers

29 13 papers had already been published, and this might reasonably lead to a new peak of studies for the current year.

Fig. I-3. Year of publication of studies included in the sample

It is interesting to notice that for the first five years since the introduction of the OI paradigm (2003-2008), while the enthusiasm towards it was spreading across the private sector (Mortara & Minshall 2011), the attention of the scholars has been mostly exploring OI and the related phenomena focusing on the processes of successful strategies, to recognize the effectiveness of openness. Once the paradigm achieved a certain level of popularity, the initial enthusiasm for the new theory started to become more structured and scholars started to explore the phenomena in its complexity, highlighting some of the difficulties that organizations face in implementing OI.

We identified the journals that included the major numbers of paper describing and/or referring to the presence of downsides embedded in the implementation of OIS (see figure 4). The R&D Management journal ranks first, with 21 papers published on the topic, out of which 10 were included in two Special Issues published respectively in 2009 (3 papers) and 2010 (9 papers). The California Management Review ranks second with 9 papers, followed by Technovation and the International Journal of Technology Management (7 papers each), Creativity and Innovation Management (6 papers), European Journal of Innovation Management (5), Research Policy and Technology and Innovation Management Review (3 papers each). The majority of the works (about 68%) are empirical studies, while only a minority is theoretical.

Fig. I-4. Top Journals per number of papers published referring to OI challenges

1 1 1 7 5 2 14 19 10 6 8 8 8 20 13 0 5 10 15 20 25 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 0 5 10 15 20 25 Research Policy

Technology and Innovation Management Review European Journal of Innovation Management Creativity and Innovation Management International Journal of Innovation Management Technovation California Management Review R&D Management

30 All the authors participated in the selection of the keywords, screening and assessment criteria, interpretation and systematization of the results. We jointly managed the decision making process and analyses in order to secure robustness to our findings (Flickr 2004).

I-4. Findings: Internal and External Challenges of the OI

At the level of analysis of Private R&D and innovation context, internal and external challenges are both present, but the external ones represent the category of challenges most commonly resulting from the studies, i.e. the ones emerging beyond organizational boundaries, on which companies have limited influential power (see table I-3). The higher frequency of external challenges in the literature is reasonable, because the most common archetype applied to implement OI is the inbound mode and it is consequently the most explored in the literature (Chesbrough & Bogers 2014). Companies need to establish close relations with the external environment to achieve useful introduction of external assets and knowledge from outside their boundaries, and this is the locus where more challenges can rise.

Tab. I-3. The taxonomy of challenges of OI in Private R&D and Innovation in extant literature

Internal Challenges External Challenges

Organizational Changes Internal Assets Protection

Cultural Changes Over-Searching

Business Model Innovation Management of External Partnerships Business Model Innovation

I-4.1. Internal Challenges

From the perspective of the internal challenges, faced within the organizational boundaries, we identify three categories of challenges: the organizational changes, the cultural changes, and the business model innovation.

I-4.1.1. Organizational Changes.

The strategies of OI are extremely pervasive and they do not concern only the R&D departments, directly responsible for producing innovation, but involve the company as a whole, including all the departments and levels. It is a company-wide strategy (Huston & Sakkab 2006) that leads to internal organizational adjustments so radical that the OI is deemed to be an “organizational innovation” by itself (Christensen 2006; Mortara et al. 2009; Di Minin et al. 2010; Casprini et al. 2013). Indeed, the implementation of OIS can create complication in the inter-organizational relationships for the higher coordination costs and complexity of the innovation processes (Enkel, Gassmann, & Chesbrough,

31 2009). Long processes of experimentation and adjustment are necessary to find a proper division of task and responsibility, balancing innovation and daily management tasks (van de Vrande et al. 2009) because the OI is a complete shift in the company’s innovation paradigm (Gassmann & Enkel 2004; Traitler et al. 2011; Chesbrough & Brunswicker 2014). This shift requires processes, resources and activities to be reconfigured and constantly monitored (Casprini et al. 2013; Elmquist, Fredberg, & Ollila, 2009; Wallin & Von Krogh 2010) because the decentralization of the innovation activities, from the R&D unit towards the entire organization (Dodgson, Gann, & Salter, 2006), can let rise boundaries among internal departments (Trott & Hartmann 2009). Once the innovation process has been diffused within the organization, there are still some units that assume a primary role in managing it within the company, the OI-led organs. They struggle in being recognized by other business units and usually lack empowerment and autonomy to lead the OIS (Di Minin et al. 2010).

The organizational changes need to happen in multi-phased processes in order to allow adaptation within the firm, but they can be strongly challenged by organizational inertia, which risks to hamper the whole OIS (Chiaroni, Chiesa, & Frattini, 2010, 2011; Mortara & Minshall 2011). To overcome this inertia, it is essential to guarantee an effective communication of the paradigm shift within the company (Kim et al. 2016): a lack of communication can affect a proper management of the human resources and innovative ideas, inhibiting the long-term sustainability of the open strategy (van de Vrande et al. 2009; Casprini et al. 2013). Therefore, companies should break internal silos and practice openness within their boundaries even before outside of them (Abu El-Ella et al. 2016; Lenz et al. 2016; Lang et al. 2017). In fact, a better cooperation among organizational units can foster higher inclination to collaborate with the external environment, providing benefits for the whole innovation activity and not only for the projects conducted under an OI approach. Finally, the organizational changes should also foresee the creation of metrics (Traitler et al. 2011) to manage and measure the effectiveness of the new strategy. That would not only avoid uncertainty (Chiaroni et al. 2010, 2011; Keupp & Gassmann 2009), but also secure adequate resources, in terms of budget, time and human resources allocation, to the OI projects (Chesbrough & Crowther 2006; Huston & Sakkab 2006; Enkel et al. 2009; van de Vrande et al. 2009; Sieg, Wallin, & von Krogh, 2010).

I-4.1.2. Cultural changes.

As said, OI is a strategy that deeply influences the internal organization embracing it and, to secure the success of this strategy, the culture of the company needs to be open. Shifting to openness implies profound cultural changes for the organization that needs to promote openness within its boundaries, nurturing internal changes towards the open culture (Huston & Sakkab 2006; Sieg et al. 2010;

32 Huizingh 2011) to sustain internal commitment to the strategy overtime (Chesbrough & Crowther 2006; Dodgson et al. 2006; Di Minin et al. 2010). Cultural changes are also needed to overcome the

not-invented-here syndrome (NIH): OIS implementation might face resistance to change from the

human resources that can potentially affect internal proactivity and willingness of collaboration success (Chesbrough & Crowther 2006; Chiaroni et al. 2010; Di Minin et al. 2010; Mortara et al. 2010; Mortara & Minshall 2011; Chesbrough & Brunswicker 2014; Kim et al. 2016). The communication mentioned among the organizational changes is also relevant in implementing cultural changes: having a strong commitment to OI by the top management levels of the organization includes making the OIS explicit within the company (Huston & Sakkab 2006). This requires explicit and clear endorsement from the higher managerial level of the firms (Ollila & Elmquist 2011; Traitler et al. 2011), which guarantees not only support in terms of resources (Chesbrough & Crowther 2006), but also in terms of vision. Opening up the innovation process involves long processes of trial and error (Laursen & Salter 2006; Chiaroni et al. 2010; Di Minin et al. 2010), studded with unsuccessful outputs and uncertainty. An OI culture consists of accepting mistakes and failures, that can only be overcame though long processes of learning by doing and failing (Di Minin et al. 2016).

I-4.1.3. Business Model Innovation

The challenge of business model innovating is widely mentioned by the literature. When the company embraces OI, this strategy needs to find the right alignment and balance with the daily business that the company traditionally conducts (Enkel et al. 2009). Especially in the early adoption of OI, the existing business model will tend to prevail and dominate innovation activities (Van Der Meer 2007): old and new strategies then start to coexist along with the phases of development of the open projects (Dodgson et al. 2006). Balancing the new openness of the organization with its previous and classic closed approach is tremendously challenging: the new business model needs to involve an equilibrium between incentives to and control of openness (Wallin & Von Krogh 2010). This means finding the adequate way to pursue projects of OI that are critical for the growth of the organization, balancing the exploitation of organizational assets and technologies, and the exploration of external opportunities and future potential development of the strategy (Di Minin et al. 2010).

The organization needs to adapt the business model including changes in the governance of the company to guarantee an appropriate management of the internal assets (human resource, knowledge, technologies, etc.) (Lenz et al. 2016), collaborations, appropriation strategy, and allocation of resources (Huizingh 2011). All these changes related to the implementation of an open approach to innovation create several difficulties. Furthermore, in order to be successful, OI has to be a long-term