POLITECNICO DI MILANO

Scuola di Ingegneria Industriale e dell’Informazione

Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Ingegneria Gestionale

A proposal for an extended Lean

framework supporting Digital New

Ventures in business model changes

Supervisor:

Eng. Antonio GHEZZI

Co – Supervisor: Eng. Angelo CAVALLO

Master Thesis by:

Pietro LOMBARDO

Matr. 834661

Academic Year 2015/2016

2

Ringraziamenti

Desidero ringraziare tutti coloro che hanno avuto un ruolo, più o meno diretto, nella stesura di questo lavoro di tesi. Prima di tutto il relatore, Prof. Antonio Ghezzi e il correlatore, Ing. Angelo Cavallo che mi hanno indirizzato lungo questo cammino iniziato nel dicembre 2014 e che culmina oggi. Ringrazio la Prof. Alessandra Colombelli che ha accettato di contribuire al mio conseguimento della doppia laurea con il Politecnico di Torino. Ringrazio tutti gli imprenditori che mi hanno concesso il loro tempo in interviste. Tra questi, Gian Luca Petrelli, Founder & Executive Chairman di BeMyEye, Vittorio Guarini, CEO and Co-founder di FazLand e Domenico Colucci, CFO and Co-founder di NexToMe. Ringrazio anche il collega Davide Trezzi per i dati messi a disposizione per la preparazione dei pre-casi. Voglio precisare che tutte le persone citate hanno svolto un ruolo fondamentale nella stesura della tesi, ma ogni errore o imprecisione è imputabile soltanto a me. Non posso non ringraziare la mia famiglia, la mia fidanzata e i miei amici che hanno reso possibile, costruttivo e piacevole questo percorso universitario che oggi volge al termine.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank everybody that contributed, directly or indirectly, to the creation of this thesis. Namely, first of all Prof. Antonio Ghezzi, supervisor, and Eng. Angelo Cavallo, co-supervisor, that guided me through a long journey started in December 2014 and that today ends. I thank Prof. Alessandra Colombelli for reviewing my work and thus allowing me to obtain the double degree with the Politecnico di Torino. I thank all the entrepreneur that gave me time for interviews. Among them Gian Luca Petrelli, Founder & Executive Chairman di BeMyEye, Vittorio Guarini, CEO and Co-founder di FazLand e Domenico Colucci, CFO and Co-founder di NexToMe. I thank my colleague Davide Trezzi for the help in gathering data for preparing the pre-case studies. I want to clarify that all the cited people had a fundamental role in the creation of this thesis, but every mistake or inaccuracy has to be imputed only to myself. Last but not least, I thank my family, my girlfriend and my friends that made possible, productive and enjoyable this university period that, eventually, ends today.

4

Table of Contents

FIGURES INDEX ... 6 TABLES INDEX ... 8 ABSTRACT ... 9 ABSTRACT IN LINGUA ITALIANA ... 10 ESTRATTO IN LINGUA ITALIANA ... 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ... 15 SMED ... 20LEAN STARTUP APPROACH ... 22

THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL: THE STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT CYCLE ... 23

RESEARCH DESIGN ... 25 RESULTS ... 29 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH ... 35 INTRODUCTION ... 37 PART 1: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 40 BUSINESS MODEL ... 40 LEAN PHILOSOPHY ... 46 SMED ... 50

LEAN STARTUP APPROACH ... 52

LITERATURE REVIEW OVERVIEW ... 54

DRILL DOWN 1: BUSINESS MODEL ... 55

Business Model Definitions ... 58

Business Model sub-areas of research ... 62

DRILL DOWN 2: LEAN MANUFACTURING ... 93

From Mass to Lean Production ... 93 Defining Lean ... 95 The Lean Manufacturing Philosophy ... 104 Sub-research areas ... 107 The Lean Implementation Process ... 108 Lean Tools ... 112 The SMED Framework ... 117 Findings and Gaps ... 124

DRILL DOWN 3: LEAN STARTUP APPROACH ... 130

Startups success factor ... 136

Critics and Alternatives ... 150

Findings, gaps and future researches ... 151

THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL: THE STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT CYCLE ... 154

RESEARCH DESIGN ... 157

5 CASE STUDIES RESULTS ... 162 BeMyEye ... 162 FazLand ... 164 NexToMe ... 165 CASE STUDIES DISCUSSION ... 167 THEORETICAL CONTRIBUTION ... 172 Business Model innovation and Lean Philosophy: touchpoints ... 172 The Changing Perspective: When a change (or changes) can be considered an innovation and when not? ... 174 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH ... 175 REFERENCES ... 177 APPENDIX ... 201

APPENDIX 1: CASE STUDY’S SCHEME OF ANALYSIS ... 201

Pre-case ... 201

Case ... 202

APPENDIX 2: CASE STUDY’S SCHEMATIC INTERVIEW OUTCOMES ... 206

BeMyEye ... 206

FazLand ... 207

NexToMe ... 209

APPENDIX 3: DATABASE ‘LITERATURE BY CONCEPTS’ SAMPLE ... 211

APPENDIX 4: DATABASE ‘LITERATURE REVIEWED’ SAMPLE ... 216

6

Figures Index

Figure 1 - SMED4BMC: Un framework integrato per il processo di cambio di BM ... 13 Figure 2 - SMED-ZERO and SMED stages representation ... 21 Figure 3 - The Strategy Development Cycle ... 25 Figure 4 - The business model canvas ... 28 Figure 5 - An integrated framework for BM change process in digital new ventures: SMED4BMC ... 32 Figure 6 - The five lean principles ... 47 Figure 7 - SMED-ZERO and SMED stages representation ... 51 Figure 8 - Business model as linkage among Strategy and Operation(Pekuri et al. 2014) ... 56 Figure 9 - From Strategy to Tactics ... 60 Figure 10 - What a Business Model is/is not ... 61 Figure 11 - Activity System Value Creation Drivers ... 65 Figure 12 - SNS BMs ... 67 Figure 13 - The Business Model Canvas ... 69 Figure 14 - Preferential path of BMD according to strategy ... 73 Figure 15 - 'Black Hole' investment strategy ... 78 Figure 16 - Option oriented investment strategy ... 78 Figure 17 - Why to Open Business Models ... 79 Figure 18 - Market Development and BMI ... 83 Figure 19 - Overall research framework ... 84 Figure 20 - Toyota Business Model ... 92 Figure 21 - Toyota Production System ... 104 Figure 22 – Åhlström framework for Lean Implementation ... 111 Figure 23 - Bicheno and Holweg hierarchical lean transformation framework... 111 Figure 24 - SMED stages representation ... 118 Figure 25 - SMED conceptual stages and practical techniques ... 119 Figure 26 - Activities and interdependencies representation ... 121 Figure 27 - McIntosh et al. reinterpretation of Shingo's SMED ... 122 Figure 28 - Incorporation of SMED-ZERO to SMED conceptual stages 124 Figure 29 - The forces opposing and driving a change to lean ... 126 Figure 30 - The uncertainty issue ... 131 Figure 31 - Lean vs Traditional Businesses ... 135 Figure 32 - Product and Customer parallel development processes .... 137 Figure 33 - 80/20 rule ... 138 Figure 34 - Experiment Board ... 140 Figure 35 - AARRR pirate metrics ... 141 Figure 36 - BML cycle ... 1437 Figure 37 - Continuous deployment cycle ... 144 Figure 38 - Tools usage along the BML loop ... 147 Figure 39 - Lean Canvas ... 148 Figure 40 - Dynamic canvas ... 149 Figure 41 - Overview of ESSSDM ... 150 Figure 42 - ESSSDM Level 2 process ... 151 Figure 43 - BM loops sequence ... 153 Figure 44 - The Strategy Development Cycle ... 156 Figure 45 -The business model canvas ... 160 Figure 46 - An integrated framework for BM change process in digital new ventures: SMED4BMC ... 169 Figure 47 - BeMyEye business model ... 206 Figure 48 - BeMyEye new business model ... 206 Figure 49 - BeMyEye business model change process ... 207 Figure 50 - FazLand business model ... 207 Figure 51 - FazLand new business model ... 208 Figure 52 - FazLand business model change process ... 208 Figure 53 - NexToMe business model ... 209 Figure 54 - NexToMe new business model ... 209 Figure 55 - NexToMe business model change process ... 210

8

Tables Index

Table 1 - Lean manufacturing principles in LSA. Touchpoint: ... 22 Table 2 - Semi-structured interview main focus ... 27 Table 3 - Bridging SMED to SMED4BMC ... 33 Table 4 - Most used Lean tools ... 49 Table 5 - Main benefits of the SMED application ... 51 Table 6 - Lean manufacturing principles in LSA. Touchpoints: ... 52 Table 7 - Literature review main findings per stream analyzed ... 54 Table 8 - Business Model Definitions ... 58 Table 9 - Overview on the business model frameworks and components ... 63 Table 10 - How Mainstream Theories Affect the Design Themes ... 65 Table 11 - Value Creation Levers per Design Element ... 66 Table 12 - The Business Model Ontology ... 68 Table 13 - Business Model Ontology Building Blocks Comparison (1) .. 70 Table 14 - Business Model Ontology Building Blocks Comparison (2) ... 71 Table 15 - Criticism to the BM concept ... 74 Table 16 - Coopetition Based Business Models ... 81 Table 17 - New SNS-based BMs ... 85 Table 18 - New BMs (1) ... 88 Table 19 - New BMs (2) ... 89 Table 20 - Main characteristics of a traditional business model and portrayed elements of a lean-driven business model for construction ... 91 Table 21 - Production Systems compared ... 94 Table 22 - Chronicle changes in Lean Manufacturing ... 101 Table 23 - The Seven Wastes ... 102 Table 24 - A comparison of lean implementation processes ... 109 Table 25 - Hobbes Lean implementation steps vs five lean principles. 110 Table 26 - Top 25 Lean tools ... 112 Table 27 - Lean thinking focus and gaps over time ... 127 Table 28 - DT vs LSA ... 134 Table 29 - Semi-structured interview main focus ... 159 Table 30 - Bridging SMED to SMED4BMC ... 170Abstract

Business Model Innovation (BMI) is a process new ventures are frequently involved in, specifically in dynamic environments like the digital one: copying with the change process from one Business Model (BM) to another is hence a key issue for entrepreneurs attempting to shorten the transition and avoid losses in terms of revenue, image and customer retention. The extant literature and practice shows fragmentation while defining and executing BMI. Moreover, past contributions focus on cases with evidence of innovation. This study wants to advance the current discussion on BM as potential source of innovation by focusing on the change process preceding and basis for a potential innovation. The author’ contributions start from understanding the greatest common factor shared among academic’s view on BMI. A view of BMI as a change process provides: a) a unified changing perspective among the extant valuable literature contributions; b) widening the potential empirical context (i.e. analyze and get insight from empirical cases where it is evident a BM change process while its innovative nature is an eventuality). After all, Innovation starts from and has its roots in an act of change.

This study is based on a specific assumption. The Lean Philosophy, already shifted from the manufacturing area and applied into the (entrepreneurial) Strategy world through [LP1] an early approach (the Lean Startup), may play a significant role in advancing the BM research in his theory and operative tools. Indeed, it offers principles and methods able to improve the execution of processes. The research findings confirm the initial assumption by presenting: a) theoretical links or touchpoints between Lean Philosophy and Business Model Innovation; b) an integrated framework, as result of the common path for BM changes identified through the case studies and formalized adapting the Lean Manufacturing tools: SMED-ZERO and SMED.

Advancing the Business Model Innovation research in his concept, through the changing perspective, and practical tools through the SMED4BMC, is only a small step ahead while opening several future

10

Abstract in Lingua Italiana

Business Model Innovation (BMI) è un processo in cui nuove compagnie sono spesso coinvolte, soprattutto in contesti dinamici come quello digitale. Diventa anche una questione strategica per imprenditori che vogliono ridurre il transitorio ed evitare danni in immagine, profitti e ritenzione della clientela. Tuttavia, la letteratura e l’evidenza empirica mostrano una frammentazione riguardo alla definizione di BMI e risultano carenti in strutturate metodologie per eseguirlo. L’attenzione della ricerca viene generalmente catturata da casi di evidente innovazione. Questo studio vuole contribuire alla discussione accademica su BM considerandolo come una potenziale fonte di innovazione e focalizzandosi sul processo di cambio che ne sta alla base. Il primo contributo dell’autore sta nel determinare il massimo comun divisore nei paper accademici sul BMI. Una visione del BMI come processo di cambio fornisce: a) una prospettiva unica con le potenzialità di avere maggiori sinergie nei futuri sforzi di ricerca; b) un allargamento del contesto empirico di studio (p.es. ai casi di cambio di BM in cui l’innovazione è un’eventualità). Dopotutto, ogni innovazione ha inizio e radici in un evento di cambiamento.

Questa ricerca è basata su una specifica ipotesi. La Lean Philosophy (LP), già adattata dal mondo della produzione e applicata nella strategia imprenditoriale tramite il Lean Startup Approach (LSA), può giocare un ruolo significativo nell’avanzamento della teoria e degli strumenti operativi in ambito BM. Infatti, essa offre principi e metodi in grado di migliorare l’esecuzione dei processi. I risultati dello studio confermano l’ipotesi iniziale introducendo: a) punti di contatto tra le teorie di LP e BMI; b) un framework integrato, come risultato del comune processo di cambio di BM identificato dai casi di studio e formalizzato con un adattamento di metodi di Lean Manufacturing: SMED-ZERO e SMED. Un avanzamento della ricerca su BMI in termini del suo stesso concetto, tramite la visione come processo di cambio, e di un nuovo strumento pratico (SMED4BMC) per la sua esecuzione è solo un piccolo passo avanti che apre numerose direzioni da esplorare in future ricerche.

Keywords: Business Model; Business Model Innovation; Lean Manufacturing; Lean Startup Approach; Entrepreneurship; Digital New

11

Estratto in Lingua Italiana

Oggigiorno le imprese sanno dì poter creare valore dall’innovazione del modello di business (BMI) in misura non inferiore che con innovazioni tecnologiche (Chesbrough 2010). Questa considerazione rimane valida sia per piccole che per grandi imprese e che affrontino cambiamenti radicali e incrementali. Famosi casi di successo sono Apple, IBM, Xerox e molti altri, mentre sono molto numerosi anche i casi di fallaci tentativi di innovazione (p.es. IKEA ‘Boklok’). Ciò porta l’autore a focalizzare la ricerca oggetto di questa tesi sul processo di cambio di un Business Model, in particolare nei primi anni di vita di un’impresa. Al filone teorico di ricerca sui BM viene affiancata un’esplorazione della Lean Philosophy perché considerata una teoria che fortemente influenza e ha già influenzato i processi di business in molti settori, dal manufacturing all’R&D passando per il digitale e diversi altri ancora. Infatti, i suoi principi e framework hanno già trovato applicazione nel mondo della Strategia (imprenditoriale) tramite il Lean Startup Approach. L’autore crede e fonda questo studio sull’ipotesi che anche la ricerca sui Business Model possa beneficiare da un adattamento e applicazione di concetti nati in Lean. Alla componente induttiva della ricerca, si unisce lo studio empirico e deduttivo di casi di studio. Un lungo lavoro iniziato nel 2012 supporta questa fase. Dati raccolti all’interno del progetto permanente di monitoraggio delle startup digitali dell’ecosistema Italiano hanno permesso di creare un database unico delle imprese fondate dal 2009 in poi. Da esso provengono i casi di studio: BeMyEye, FazLand e NexToMe. Scelte perché appartenenti al dinamico ecosistema, queste imprese con 3-4 anni di vita, hanno sperimentato e continuano a sperimentare un processo di cambiamento del business model. Inoltre, per incrementare la generalizzabilità dei risultati, queste tre imprese sono state selezionate perché hanno affrontato la transizione tra i BM in modi molto differenti: (i) introduzione di un Wizard of Oz test (ii), semplice comunicazione per preparare il cliente (iii), mantenimento in parallelo del vecchio e del nuovo modello di business.La letteratura e l’evidenza empirica mostrano una frammentazione riguardo alla definizione di BMI e risultano carenti in strutturate metodologie per eseguirlo. L’attenzione della ricerca viene generalmente

12 catturata da casi di evidente innovazione. Questo studio vuole contribuire

alla discussione accademica su BM considerandolo come una potenziale fonte di innovazione e focalizzandosi sul processo di cambio che ne sta alla base. Il primo contributo dell’autore sta nel determinare il massimo comun divisore nei paper accademici sul BMI. Una visione del BMI come processo di cambio fornisce: a) una prospettiva unica con le potenzialità di avere maggiori sinergie nei futuri sforzi di ricerca; b) un allargamento del contesto empirico di studio (p.es. ai casi di cambio di BM in cui l’innovazione è un’eventualità). Dopotutto, ogni innovazione ha inizio e radici in un evento di cambiamento. Infatti, questa ricerca ha ottenuto interessanti frutti dall’analisi di casi di studio dove è avvenuto un cambio di BM ma un’innovazione non è oggettivamente riconoscibile. La loro esplorazione ha, infatti, permesso di trovare un cammino comune di esecuzione di un processo di cambio di BM e una serie di prerequisiti che favoriscono il transitorio.

Il confronto del pattern identificato con i modelli SMED ZERO e SMED dalla Lean Manufacturing permette un’estensione dei risultati (data dalla combinazione di approccio deduttivo e induttivo) e una loro formalizzazione in un nuovo frameworks ‘SMED4BMC’ - SMED per i Cambi di BM che può anche essere usato per supportare l’esecuzione di BMI, contribuendo così al secondo gap identificato. Questo strumento risulta valido per cambi di BM visti come potenziale fonte di innovazione anche se non ancora tali.

SMED4BMC permette una riduzione della durata del processo di cambiamento percepita dal cliente anticipando gli interventi nella parte sinistra della canvas di Osterwalder, creando così consistenza interna, (stage 1) e una migliore gestione del transitorio grazie a una fase in cui viene curata e personalizzata la relazione con il consumatore preparandolo, insieme all’impresa, all’innovazione (stage 2).

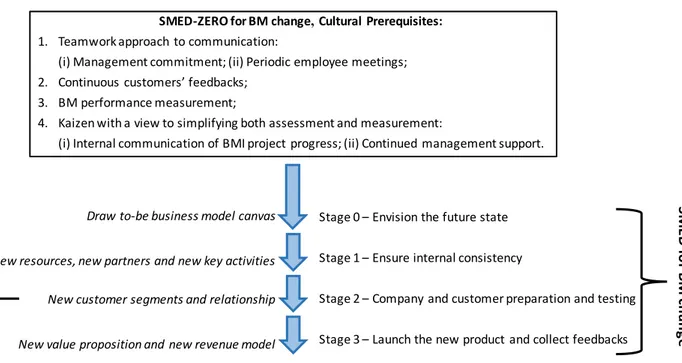

13 In forma schematica e riprendendo le terminologie dello SMED: Figure 1 - SMED4BMC: Un framework integrato per il processo di cambio di BM L’applicazione del modello SMED, preferibilmente dopo la preparazione richiesta da SMED-ZERO, produce benefici come (i) la riduzione del periodo di sovrapposizione tra BMs visto dal cliente, (ii) una gestione appropriata della fase di introduzione di un nuovo BM, (iii) la possibilità di testare il BM finale tramite un passaggio intermedio dedicato alla relazione con il cliente e (iv) la riduzione degli sprechi di risorse per la gestione dei clienti in transitorio. I risultati dello studio suggeriscono che alcune startup sperimentano condizioni di BM multipli per esplorare nuove opportunità. La loro coesistenza può essere vista come una ‘confusione strategica’ che garantisce flessibilità invece che solo come un rischio. Ulteriori studi possono integrare considerazione su tale fenomeno sullo stesso modello SMED4BMC.

L’analisi di letteratura ha portato l’autore a contribuire alla ricerca in ambito BM anche identificando dei punti di contatto tra BMI e Lean Philosophy: (i) la prospettiva di BMI come un processo lean, potenzialmente economico e flessibile, per creare valore; (ii) la continua ricerca di miglioramento è un processo caratteristico della filosofia lean e viene ritrovato anche nella letteratura su BMI sotto il termine di ‘continuous business model innovation’ (Mitchell and Coles 2003); (iii) BMI è un processo di cambiamento e, in quanto tale, può beneficiare da SMED-ZERO for BM change, Cultural Prerequisites: 1. Teamwork approach to communication: (i) Management commitment; (ii) Periodic employee meetings; 2. Continuous customers’ feedbacks; 3. BM performance measurement; 4. Kaizen with a view to simplifying both assessment and measurement: (i) Internal communication of BMI project progress; (ii) Continued management support. Stage 0 – Envision the future state Stage 1 – Ensure internal consistency Stage 2 – Company and customer preparation and testing Stage 3 – Launch the new product and collect feedbacks New resources, new partners and new key activities New customer segments and relationship New value proposition and new revenue model Draw to-be business model canvas SM ED fo rBM ch an ge

14 applicazioni di teorie, come la lean, per gestione di processi. Questi punti di contatto e le analogie che hanno portato alla costruzione del modello confermano l’ipotesi iniziale su cui questo studio si fonda.

15

Executive Summary

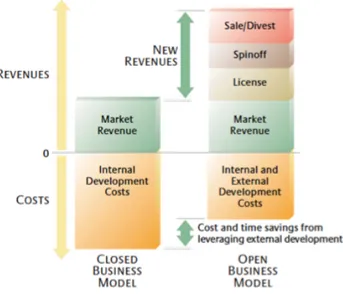

Nowadays, companies are aware that they can gain value from Business Model Innovation (BMI) in a measure not inferior than innovating through a new technology (Chesbrough 2010). This holds true for big and small organizations and for incremental and radical changes (Mitchell and Coles 2003; Klewitz and Hansen 2014).

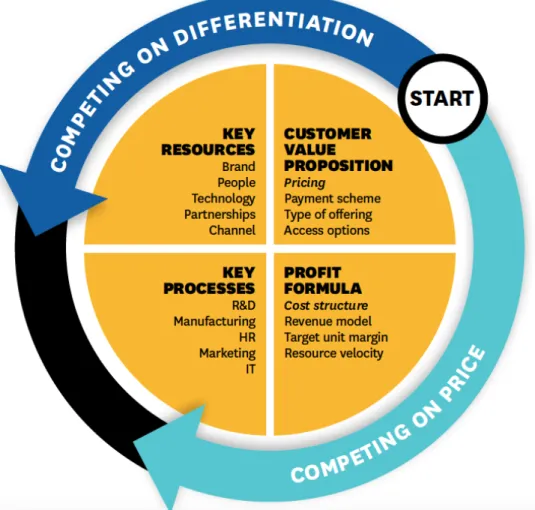

Famous success cases involved Apple, IBM, Xerox just for mentioning some. It is not difficult to find situations of flawed BMI that damaged companies (e.g. IKEA ‘Boklok’) (Halecker et al. 2014).

The increasing number and frequency of BMI (Lindgardt et al. 2009), coupled with its potential results on firm’s performance, makes the ability to competently innovate a BM a source of competitive advantage (Mitchell and Coles 2003). Research found that when structural changes occur, firms that accomplish a fast BMI, on average, enjoy greater benefits and enable a growth process (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010). This study is focused on the Business Model change process occurring in the early stage of a new venture. In the first part of the literature review the author will present a short overview on the BM, as static concept, but also referring to its dynamic and potential innovative nature. It is followed by an exploration of the Lean Philosophy, as a powerful theory influencing deeply the business processes across many industries. Already shifted from the manufacturing area and applied into the (entrepreneurial) Strategy world through the Lean Startup Approach, the Lean Philosophy may play a significant role in advancing the Business model stream of research in his theory and operative tools.

The theoretical stream of Business Model (BM) springs from strategic management theories such as the transaction cost economics, resource-based view, system theory and strategic network theory (Amit and Zott 2001; Hedman and Kalling 2001; Morris et al. 2005).

Studies on BM are relevant for several reasons and in numerous industries.

First of all, BM is the integration point among different theories and is considered as the new comprehensive unit of analysis (Amit and Zott 2001; Kurti and Haftor 2014).

Chesbrough (2007) infers that a company analysis through BM is superior to traditional considerations (e.g. position within an industry). The business model concept is integrative in nature (Pekuri et al. 2014). Secondly, BM has the ability to formalize assumption and ‘tell a story’ makes everyone in the organization aligned on common values and

16 goals (Magretta 2002). The resulting collective knowledge increases

chances of survival of a firm (Greve 1998). BM can be a source of competitive advantage (Zott et al. 2011; Allan and Christopher 2001; Doz and Kosonen 2010; McGrath 2010), so revealing its ‘strategic’ nature.

Successful companies consider BM change and adaptation an imperative to exploit new opportunities (Achtenhagen et al. 2013) and it is a continuous experimentation and trial and error learning process (Morris et al. 2005) that not always succeeds (Kurti and Haftor 2014).

Adopting a dynamic perspective when referring to the business model is a mandatory strategic approach in the current constantly and quickly changing business environment. Thinking at how to set up a process of continuous change, adaptation and innovation will be more and more often the core of the business planning process.

An interesting perspective of Business models is offered by Demil and Lecocq: ‘Business model of a given organization is a snapshot, at a given time, of the ongoing interactions between these core components. But, rather than a snapshot, we should perhaps think of this image as a single frame from a motion picture’ (Demil and Lecocq 2010) The ‘movie’ is the result of a series of sequential BMs that are planned, designed and tested as a result of internal or external triggers (Sosna et al. 2010).

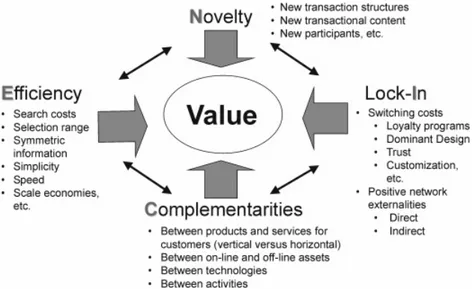

Several scholars refer to the BM as the process through which an organization creates, delivers, and captures value (economic, social, or in other forms) in relationship with a network of exchange partners (Osterwalder et al. 2005; Zott et al. 2011; Allan and Christopher 2001). A broad definition that serves the scope of introducing BMI (Massa and Tucci 2013).

Osterwalder and Pigneur about BMI, say: “rarely happens by coincidence […] It is something that can be managed, structured into processes, and used to leverage the creative potential of an entire organization.”(Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010 p. 246). Amit and Zott (2012) and Johnson, Christensen and Kagermann (2008) underline that BMI is an intended activity.

The extant literature and practice shows two main gaps. First, a need of theoretical contribution around the Business Model Innovation concept

17 very used by several scholars but still with few definitions and

discussions about the concept itself (Berglund and Sandström 2013, Morris et al. 2005, Chesbrough 2010, Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010). Second, a lack of methodologies for executing a BMI process.

The past academic contributions focus on cases with a clear evidence of innovation. This study wants to add its contribution on Business Model as potential source of innovation by focusing on the change process preceding and basis for a potential innovation.

Revisiting the BMI concept, a valuable and broad definition has to be mentioned. Business Model Innovation process is first of all a ’change phenomenon’ that, if characterized by some degrees of novelty or uniqueness comparing to already existing solution in the market, can lead to a business innovation process (Massa and Tucci 2013). A change phenomenon can be materialized trough the design of novel BMs for new ventures, called Business Model Design, or the transformation of existing BMs, called Business Model Reconfiguration (Massa and Tucci 2013). Our focus on new venture, justify few more comments around the Business Model Design (BMD) concept. Erroneously the BMD can be seen as a process ending with the first and ex-ante creation of content, structure and governance of the transactions that makes the new venture in condition to perform a value creation and capturing process. BMI has also been described as a ‘deviation from the inherited dominant logic of the firm [and] further inquiry about […] the implications of these change processes for corporate strategy might be interesting to pursue’ (Spieth et al. 2014). In accordance to Massa and Tucci (2013), Spieth et al. (2014) argue that a new business model configuration is not an activity that happen once and then finish, but an ongoing research of the optimal way for (1) explaining, (2) running and (3) developing the business.

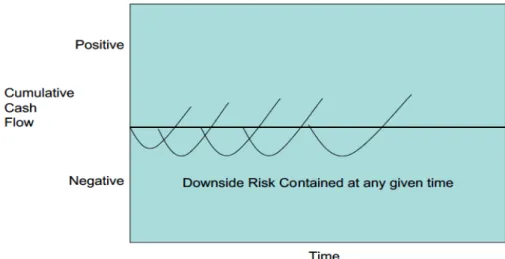

The entrepreneurial activity is characterized by high level of uncertainty (McGrath 2010), and this is only amplified in the digital sector. The uncertainty is not only generated by the more dynamic and unpredictable contest but it comes also from the network of non-linear interdependencies between the Business Model own components and the value network in which it operates. The Business Model present all the characteristics of dynamic complexity (Massa and Tucci 2013) - i.e. feedback loops, time delays etc. (Sterman 2001). This makes evident that the BMI includes a period of experimentation, learning, improvement, testing, validating. Learning and changing phenomena that can last one

18 year, two or more until the company finds his way to become sustainable and competitive in the market. It is noteworthy explicit that not all the Business Model Design process can lead to BMI according to Massa and Tucci (2013). The perspective presented above does not clearly state the border line for outlining when a Business Model Change process can be considered Business Model innovation. An interesting attempt that goes in this direction is actually earlier than Massa and Tucci’s approach. Mitchell and Coles (2004), starting from a very simple definition of BM (i.e. ‘A business model comprises the combined elements of ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘when’, ‘why’, ‘where’, ‘how’ and ‘how much’ involved in providing customers and end users with products and services’) argue that BMI process can start with changing a single business model element - business model improvement - that can become replacement if it entails improving at least four of these business model elements versus the competition. And finally as last step of a continuous changing phenomenon a business model replacement providing services or products not previously available, can be considered business model innovations. Mitchell and Coles (2003), underline the strategic importance of a process of continuous changing phenomena leading to a continuous business model innovation.

‘The process of continuous business model innovation occurs when a company pursues an ongoing process of developing and installing business model improvements, replacements and innovations’ (Mitchell and Coles 2004).

When a change (or changes) can be considered an innovation and when not? Massa and Tucci (2013) argue that it depends on the degree of novelty of that change comparing to already existing solution in the market. Mitchell and Coles (2004) stressed the number of changes over the nature of a single change.

However, the business model change and its innovation dimension deserve some further discussion advancing the current understanding. In the literature, many scholars easily address the term BMI when talking about incumbent companies. Less often they address the term on new venture although the need of a continuous business model innovation is even more perceived when thinking about new ventures operating in a digital context. For them Change becomes a permanent state, a fine-tuning process and firms sustainability depends on the capacity of anticipating and responding to changes (Demil and Lecocq 2010). Demil

19 and Lecocq (2010) call dynamic consistency the firms’ ability to keep high

level of performance while building a new business model. Experimentation often requires a long period of co-existence between current and new model and organizational problems can arise (Chesbrough 2010). Indeed, a multiple business model configuration has several risks such as cannibalization and compromising quality and network. Massa and Tucci (2013) suggest to keep the different BMs in separated business units and to analyze in a 2x2 matrix the conflict level and the similarity level for preparing the organization in accordance to the outcome. There is a need for tools and practices helping entrepreneurs coping with this crucial process of change.

The author reviewed also the literature of Lean Philosophy. Already shifted from the manufacturing area and applied into the (entrepreneurial) Strategy world through the Lean Startup Approach, the Lean Philosophy may play a significant role in advancing the Business model stream of research in his theory and operative tools.

The Lean Philosophy originated after the end of the Second World War together with an evolution of the customer’s needs and expectations from a homogeneous to a heterogeneous set. The American industrial paradigm of ‘mass production’ was not able anymore to fulfill them. In the 1950s, Eiji Toyota and Taiichi Ohno started a process of adaptation of Toyota and its production systems to consumers, in order to sustain and create competitive advantage (Costa et al. 2013). This allowed the Japanese firm to gain the world production leadership against the USA. Five simple principles made it possible (Womack and Jones 1996):

1. Create value for the customer. Value is created when internal waste decreases since costs are reduced, and is increased by offering new services or functionalities valued by the customer (Hines et al. 2004).

2. Identify the value stream. The concept of value stream wants no privacy. Each firm’s costs become transparent among the supply chain partners (Womack and Jones 2010).

3. Create flow. To create flow is the principle that wants to avoid any stop in the value stream. Main causes are production changes, breakdowns, batches in quantity or in time, lack of necessary information and re-entrant loops.

20 4. Produce only what is pulled by the customer. It implies

high responsiveness while producing top-gamma quality products in an efficient and valuable way (Todd 2000). The production pull is extended up to the suppliers and the whole upstream supply chain (Hines et al. 2004). 5. Pursue the perfection by continuous identification and

elimination of waste.

Since the ‘50s, the lean principles have been applied in a number of tools supporting manufacturing. Their number has been increasing every day (Schonberger 1983, Dillon 1985, Barker 1994, Liker et al. 1995, Cusumano and Nobeoka 1998, Liker 1997, Feld 2000, Taylor et al. 2001). They are developed for different purposes (Dick and Green 2001) and exist with multiple names, partially overlapping among each other and with different application methods (Pavnaskar et al. 2003). Lean frameworks allowed Toyota to reach a yearly productivity increase double then competition, to captures 50% of market growth while keeping quality at the top.

A complete review of each of each tool is out of this paper scope, but an emphasis on the SMED method will be the core of the next section. The choice comes from the following consideration. While tools have the common point to crucially lead to change processes capable to improve the way of executing, from a single and small task to the overall organizational philosophy, SMED is the method tailored for supporting a change process in itself.

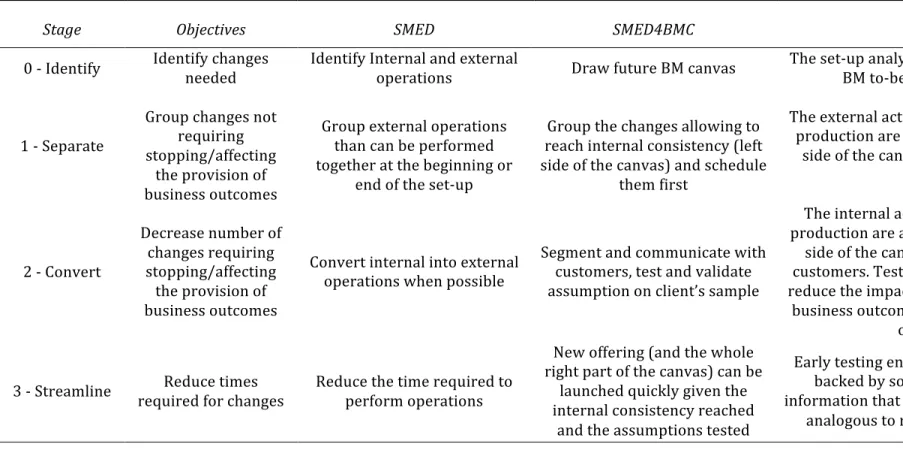

SMED

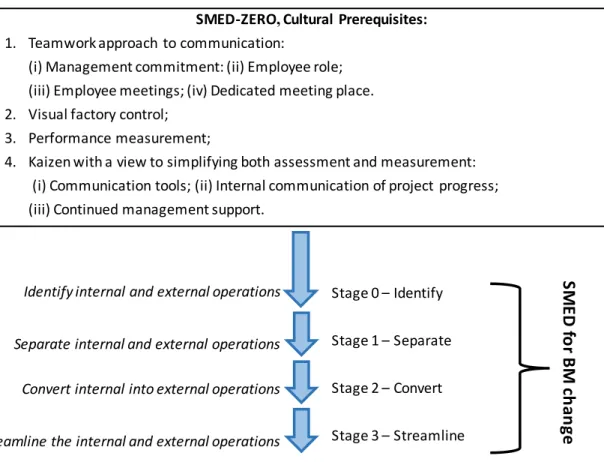

The Single Minute Exchange of Dies is a method developed in the Toyota Production System enabling a change process i.e. ‘the execution of setup processes in less than ten minutes’ (Shingo 1985). The possibility of having a faster change process leads to higher flexibility and responsiveness of the organization to the customer demand.Recently, Moxham and Greatbanks (2001) suggested that an effective SMED implementation needs a starting point that is a group of basic requirements classified as SMED-ZERO. Those involve an effective teamwork approach to communication, a visual control and management of performance and a continuous effort for simplifying both assessment and measurement.

21 Once the prerequisites are fulfilled, the SMED methodology can take

place. It is composed by four distinct phases. In the separation stage, elements that can be performed with little or no change while the equipment is running are moved ‘externally’ to the changeover (i.e., performed before or after the changeover). This stage is fertile ground for quick wins. In the conversion phase the remaining elements are examined to determine if they can be modified in some way to be external, or if they can be eliminated. The result is a list of candidates for further action. This list should be prioritized so the most promising candidates (i.e., the ones with the best cost/benefit ratio) are acted on first. Finally, during streamline, the remaining elements are reviewed with an eye towards simplifying or changing them so they can be completed in less time. Top priority should go to internal elements to support the primary goal of shortening the changeover time. As in the previous stage, a simple cost/benefit analysis should be used to prioritize actions. Figure 2 - SMED-ZERO and SMED stages representation SMED-ZERO, Cultural Prerequisites: 1. Teamwork approach to communication: (i) Management commitment: (ii) Employee role; (iii) Employee meetings; (iv) Dedicated meeting place. 2. Visual factory control; 3. Performance measurement; 4. Kaizen with a view to simplifying both assessment and measurement: (i) Communication tools; (ii) Internal communication of project progress; (iii) Continued management support. Stage 0 – Identify Stage 1 – Separate Stage 2 – Convert Stage 3 – Streamline Separate internal and external operations Convert internal into external operations Streamline the internal and external operations Identify internal and external operations SM ED fo rBM ch an ge

22

Lean Startup Approach

Even if lean was born in the manufacturing context, its principles have been valid and their impact have been significant in several different fields. For Example, in ‘Making R&D lean’, Reinertsen and Shaeffer (2005) show as a careful implementation of this philosophy can enhance R&D results and psychological motivation in the exploration activity. Similarly, Ries (2011) started adapting the principles to the strategic entrepreneurship area by elaborating the lean startup approach (LSA). The following table emphasizes how LP ideologies have been transferred in LSA: Table 1 - Lean manufacturing principles in LSA. Touchpoint: Lean Manufacturing Principles Lean Startup Process Create value for the customer Minimum Viable Product (MVP) Identify the value stream Lean Canvas Create flow Continuous Deployment Cycle Produce only what is pulled by the customer Get out of the building (GOOB) Pursue the perfection Build-Measure-Learn (BML) cycle

The Minimum Viable Product, as central concept of the Lean Startup Approach, explicits the need to focus on creating only what the customer really values. It can even be pursued with a front-end product backed by humans instead that automated (Wizard of Oz testing) (Kefalidou and Sharples 2016). This methodology is the cheapest way for verifying hypothesis that can be tracked on Lean Canvas. Indeed, the Lean Canvas is used to identify the way of delivering value to the customer by documenting assumptions, and measuring and communicating their progress/changes over time (Maurya 2012). Once it consolidates the value stream, the continuous deployment cycle is the way for minimizing every type of lead time by immediately deploying new code thus creating flow. The framework includes steps of Commit-Test-Deploy-Monitor (Olsson et al. 2012). The voice of the customers pulls what an organization produces and it is heard by asking them directly,

23 getting out of the building. Along all the organizational processes,

continuous testing (measure), learning and improvement (build) are key factors for pursuing the perfection (Maurya 2012).

LSA is an exemplary case of how the (Entrepreneurial) Strategy field can benefit from applications of LPs. The author believes there is still room for exploiting mature and consolidated tools and principles of lean for supporting and expanding other research areas. The author will elaborate more on this reflection in the next paragraphs.

The Conceptual Model: The Strategy Development Cycle

While reviewing the extant literature on the Lean Philosophy become evident and clear the exploiting phase in the Manufacturing field is - as expected due to his long history- in his maturity stage. The Development Cycle of a new ‘Strategic Thinking’ goes from its theoretical and conceptual acknowledgment to its operationalization process (meaning its translation in operational terms: tool and practice) to the execution process, revealing the strategic nature of the overall Philosophy through the impacts extended to several industries. The Lean Philosophy Development Cycle, can be considered complete in the Manufacturing field, although this does not mean finished due to: (i) its continues application that feeds many organizations and (ii) an always valid and concrete possibility to build new tools according to the changes and the evolution of the competitive context.

While, considering the extension of the Lean Philosophy in the Entrepreneurship field (i.e. The Lean Startup Approach), the Development Cycle is only in is starting point due to: (i) lack of a full theoretical and conceptual acknowledgment; (ii) few tools enabling the Strategy Operationalization Process; (iii) few cases with a concrete evidence of the strategic impacts generated by applying the Lean Philosophy.

The theoretical and conceptual acknowledgment, the Strategy Operationalization Process and Its execution phases can not be represented as in a linear and static relation. Actually, it is also wrong to use the word phases, and more appropriate would be using the term elements of the Development Cycle of a Strategic Thinking. Every advance in a single of those elements can be beneficial in enhancing the others, and contributes to the overall Strategic Thinking acknowledgment. At the actual stage of the Development Cycle a theoretical intuition could be beneficial as well as focusing on the impacts generated by using existing tools and practice.

24

The author focuses on the Strategy Operationalization process, presenting a new tool improving a specific process: The Business Model change process. The path followed to build a new tool involves: i) an extensive exploration of a strategic thinking (i.e. The lean Philosophy from its origin), considering the potential and significant role the author believes may play in advancing the Business model stream of research (Figure 3 – arrows a); ii) case studies performing business model change process, presented in the second part of the study (Figure 3 – arrow b).

Exploring a strategic thinking (as the Lean Philosophy) by itself is not sufficient for a Strategy Operationalization Process, so learning from empirical observation - e.g. through Case studies - is crucial.

Case studies analysis means, while referring to the conceptual reference model (Figure 3), study the ‘Strategic Impact’ i.e. where a certain Philosophy or Strategic Approach is expressed and becomes source of competitive advantage for the company object of study. As represented in the conceptual model, it is, therefore, noteworthy to point out how the ‘Strategic Impacts’, besides being a concrete expression of a strategic thinking and the execution of a certain strategy through specific tools and practice, can be part of the theory building process and above all, act as source of inspiration in the building process of new strategic tool/framework.

The conceptual model, described above and represented in Figure 3, makes explicit that while the present study is addressing its main contribution on the current discussion regarding the Business Model Innovation field, it is located in the broader field of entrepreneurship and can have an impact on the overall process of entrepreneurial strategy formulation and development process. Several scholars will argue the different nature of the two main streams of research analyzed. They may find not clear the bridge between a topic born at strategy level as BMI and the LP, considered more related with the operations field. However, LP has strategic impacts due to the strong influence on the performance of the company as a whole. LP has to be considered a strategic matter and the author cannot ignore that a BMI process - even though the uncertainty level in high - can be favored and smoothed thanks to targeted actions, such as usage of tools, at operational level.

25 Figure 3 - The Strategy Development Cycle [1] (Liker 2004) [2] (Marmer and Herrmann 2011) [3] (Eisenmann et al. 2012)

Research Design

The research is based on a wide systematic literature analysis and it will be carried out relying on the Case Studies methodology (Yin 2013). The systematic literature review focused on the following pillars:1. Lean Philosophy (in its application in the Manufacturing and Entrepreneurial Strategy fields);

2. Business Model theories.

The source selection process was carried out by starting from specific top academic outlets to further extend and refine the analysis by means of the EBSCO Business Source Complete database. Papers collected were

26 analyzed and archived in terms of a set of information (e.g. authors, year,

title, source, keywords, abstract, methodology, stream of research, research questions, key findings) – see appendixes 3 and 4.

The systematic literature review, focused on the Lean Philosophy (including its application in the fields of Manufacturing and Entrepreneurial Strategy) and on Business Model theories, has being conducted on the basis of four steps: (i) source identification, (ii) source selection, (iii) source evaluation, and (iv) data analysis (Bryman 2012; Hart 1998). The Literature review (LR) started from a preliminary step in which the investigator should acquire knowledge about the domain of interest, to identify the correct perspective as well as possible gaps or extensions to previous studies (Seuring and Müller 2008). The source selection process - scouting of data and corresponding sources (paper or electronic), chose according to objectives and views on the research topics – became a crucial part of LR, as it marks the border of the analysis (Mayring 2000). Once selected, sources were classified and further evaluated. Data were catalogued through technological tools, such as databases (Mayring 2000), which facilitate the recollection and analysis of information (Ferfolja and Burnett 2002).

Focusing on the most cited articles containing the main keywords related to the research topic in the title, the initial search took into consideration also a number of additional databases (e.g. those of online publishers such as Blackwell, Elsevier, Emerald, Sage Publishing and Wiley, together with other portals as Abi/Inform) exploited to cross-check the findings obtained from the EBSCO Business Source Complete. Then, a sample of 78 papers was selected based on the following criteria: firstly, many articles have been discarded because, starting from the abstract, they did not provide significant contributions to the research topic concepts with respect to the previous literature or because they were already included in other analyzed papers; other papers were excluded since deemed too specific to certain companies in a specific industry or country. The sample of papers has been chosen for representing different views in the time range 1994 to 2015 and they adopt diversified methodology for presenting their outcomes (conceptual, qualitative – case of study, qualitative – collaborative research, qualitative – survey, quantitative – statistical analysis, quantitative – mathematical modelling). This variety enable a broad view on the fields studied.

27 Subsequently, the systematic literature review informed a multiple case study, which has been performed through semi-structured interviews – both face-to-face and phone interviews – with entrepreneurs of Italian Digital startups. It was divided in a preliminary phase (PRE-CASE based on secondary sources) and an actual CASE with interviews aiming at understanding more the BM (section I – first half of the interview) and the process of BM change (section II - second half of the interview). A detail of the questions guiding this exploration can be find in the Appendix 1. The following table wants to outlines briefly the main thematic characterizing and dealt within each of the multiple case study parts, such as the investigation of pre-existing knowledge of lean in the organization and the analysis of how changes from the past to the current BM have been managed. Table 2 - Semi-structured interview main focus

Phase PRE-CASE CASE

BM BM change

Question’s Topic

Records; Current and Past BM canvas components: Value Proposition, Customer Segments, Revenue Streams, Channels, Customer Relationships, Key Resources, Key Activities, Key Partners, Cost Structure. Pre-existing Organizational Culture; Finance; Change Process Management; Team; Key Learning;

History. Presence of pre-existing knowledge of Lean.

The output required by the phase Case, section BM, is the business model canvas. It is a way of graphically representing, in a ’snapshot’ (Demil and Lecocq 2010), how a company does business. The tool has been developed by Osterwalder (2004) and is represented in the following figure. The model includes only internal factors (Osterwalder 2004) distributed among 4 areas (product, customer interface, infrastructure management) and 9 building blocks enabling a one-page representation of a company (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010). The left part of the canvas includes internal resources, activities, costs and partnership needed to run the business. The right one is the face of the business, what is visible by the customer and includes, among the others, the revenue model and the value proposition. This representation has been chosen by the author as it is the most used by practitioners while building a strategy plan

28 (Guemes-Castorena and Toro 2015; Rytkönen and Nenonen 2014). Often,

academics and practitioners’ worlds show a certain distance, speaking different language. This study wants to reduce the barrier among academic and practitioner. The selection of a toll that is increasingly used by entrepreneurs such as the Canvas can enable a more fruitful communication, especially during interviews (Salgado et al. 2014), reducing distance among academic and practitioner world.

Figure 4 - The business model canvas (Osterwalder 2004)

This qualitative model of investigation was considered particularly suitable for achieving the research objectives before explained.

They enable a holistic understanding of complex facts intertwined and difficult to separate and analyze from their contexts (Halinen and Törnroos 2005; Yin 2013), thus favoring the creation or extension of theory.

The semi-structured nature of the interviews made it possible to start from some key issues identified through the literature, but also to let innovative topics emerge – consistently to the research objectives, which aim at creating a framework supporting the execution of BMI change and coping with transitory phases.

29 The research is enabled and supported by a long and detailed empirical work started in 2012 and lasted four years. Data were gathered within a permanent project monitoring digital startups in the Italian ecosystem, which allowed to create a unique dataset including a selection of best performing startups (in terms of: (i) highest financing round; (ii) highest turnover; and (iii) highest exit value) founded from 2009 onward and that were funded by formal investors from 2012 to July 2015. Three cases are presented in this study (selected from a wider empirical research carried out within a permanent project monitoring hi-tech Startups in Italy since 2012).

The cases were selected since (i) they all faced a business model change process as source of potential innovation, (ii) the three new ventures undertook the transition phases in a deeply different way, thus increasing results generalizability.

In the timeframe February-July 2015, ten qualitative interviews (lasting one hour and thirty minutes on average) on the three cases were performed, involving the key strategic decision makers in the new ventures (i.e. entrepreneurs, founders, collaborators).

The data gathering process was based on a combination of sources: secondary sources (research reports, websites, newsletters, databases, conference proceedings) and interviews (primary source of data); this, in order to allow the triangulation of data, essential to ensure rigorous results in qualitative research (Yin 2013).

The case studies’ scheme of analysis focused on exploring the entrepreneurs’ strategic choices during the BMI process, as well as the explicit or implicit use of lean principles. The use of a multiple case study could strengthen the ability to generalize results (Yin 2013).

Results

After presenting the previous studies on Business Model concept in its static and dynamic view, the literature review explores the Lean Philosophy (from its origin), as Strategic Thinking, that may play a significant role in advancing the Entrepreneurial Strategy field and more specifically the Business Model change process of new digital ventures. However, exploring a strategic thinking (as the Lean Philosophy) by itself is not sufficient for a Strategy Operationalization Process, so learning from empirical observation - e.g. through Case studies - is crucial.

30 The three case study selected and below presented will be essential to pursue a Strategy Operationalization Process, i.e. the creation on a new framework that could lead the business model change process. This study aims to build a framework that guides entrepreneurs while managing a transitory phase from an old business model to a new one, answering the question how can be managed a business model change. In other word the decision of which component of the business model has to be changed it has already been made, and it is not a matter of investigation in this study. The multiple case study relies on three cases of new ventures selected since a business model change process and the related transition phase occurred; moreover, each cases shows an original fashion in facing the business model change and the transition phases. This will increase the generalizability of results while providing an integrated framework: (i) introduction of new product through Wizard of Oz testing before the new BM – BeMyEye case, (ii) immediate change of service after communication to customers – FazLand case– and (iii) ongoing coexistence of old and new business model with switched focus – NexToMe case.

Interviews revealed that effective BM change process requires the pre-existence of a ‘fertile ground’. Management commitment, continuous customer feedbacks and management support are key prerequisites for a proper transition phase. Moreover, metrics used and the teamwork approach to communication with periodic employee meetings are significant factors. Among those, continuous customers’ feedbacks have been mentioned by all the entrepreneurs interviewed as a core capabilities needed to perform BM changes in accordance to the customer development theory (Blank 2006).

When starting the process of BM change, new ventures formalize how they envision the future state. Even in startup with low internal bureaucracy, this preliminary stage is a driver of positive performance. The first practical step performed by BeMyEye is the scouting of new resources and the preparation of new activities that have been identified as value adding. Fazland starts coding new functionalities and preparing the new key activities that will be done after the change process in order to reach higher scalability. NexToMe acquires new partners, resources, competences and develop a new unique application. The case studies reveal a common pattern: changes are introduced starting from the ‘left

31 side’ of the Osterwalder canvas, i.e. internal value infrastructure. This

allows enhancing efficiency and scalability and reducing the time of transition among BM from the client perspective thanks to the provided internal consistency. Secondly, companies prepare themselves and the customer for the change. BeMyEye introduce a Wizard of Oz testing version of the new product for communicating directly to the clients during the change process. FazLand begins a phase of customer segmentation for better addressing clients’ needs. NexToMe tests the new market segments by launching a limited version of the unique APP only in the play store. The conversion starts taking place. Finally, when the company and the customer are ready for facing the change in the service, the last modification in the business model canvas can be implemented: i.e. the new revenue model and new value proposition. These findings imply the creation of an internal consistency before modifying what is offered to the customer. The concept is coherent with the LSA vision: ‘customers are always first’. Indeed, like the FazLand and the BeMyEye cases suggests, proper communication or even a Wizard of Oz testing can be beneficial before the introduction of the new business model. Customers are still a fundamental part of the transformation but first the the left side of the canvas need to be prepared. For instance, NexToMe acquired new partners, resources, competences and develop a new unique application before launching a test in the Google play store. Yet, communication with customers is an essential phase that can create loops back to a new modification of the left part of the canvas. However, it is important that they happen in testing phase, before the new value proposition and revenue model have been launched for keeping the process lean.

Another interesting finding that open future research directions comes from the NexToMe case. The company had a peculiar process of change that does not led to substitute the old business model, but to a coexistence on multiple business models (MBMs). It suggests that there are situations in which MBMs is identified and pursued as an opportunity. NexToMe shifts its focus from software to services provisioning without abandoning the previous activities. While a MBM may not be sustainable as startups scale and consolidate (Doz and Kosonen 2010, Massa and Tucci 2013), startups often inherently look for a MBM condition to experiment and scan for opportunities. Therefore, the coexistence of more than one business model may be perceived by entrepreneurs as a sort of ‘strategic fuzziness’ startups seek for to remain flexible (rather than a mere risk). Nonetheless, MBM strategic orchestration in a new venture needs to be supported by strategic tools enabling to seek and

32 exploit opportunities while countering risks of misalignment,

inconsistency, unclear direction and resources waste.

Summing up, the common path for BM changes identified through the case studies has been formalized adapting the Lean Manufacturing tools, SMED-ZERO and SMED.

Figure 5 - An integrated framework for BM change process in digital new ventures: SMED4BMC The integrated framework presented, called SMED4BMC, is composed by two parts. The first one supports and lists prerequisites enabling an organization to perform smooth changes to the Business Model (SMED-ZERO). The second part represent the ‘core’ part of the integrated framework. SMED-ZERO for BM change, Cultural Prerequisites: 1. Teamwork approach to communication: (i) Management commitment; (ii) Periodic employee meetings; 2. Continuous customers’ feedbacks; 3. BM performance measurement; 4. Kaizen with a view to simplifying both assessment and measurement: (i) Internal communication of BMI project progress; (ii) Continued management support. Stage 0 – Envision the future state Stage 1 – Ensure internal consistency Stage 2 – Company and customer preparation and testing Stage 3 – Launch the new product and collect feedbacks New resources, new partners and new key activities New customer segments and relationship New value proposition and new revenue model Draw to-be business model canvas SM ED fo rBM ch an ge

The following table explicates the adaptation process bridging SMED to SMED4BMC:

Table 3 - Bridging SMED to SMED4BMC

Stage Objectives SMED SMED4BMC Analogies

0 - Identify Identify changes needed Identify Internal and external operations Draw future BM canvas The set-up analysis is analogous to envision the BM to-be and gaps with the as-is

1 - Separate Group changes not requiring stopping/affecting the provision of business outcomes Group external operations than can be performed together at the beginning or end of the set-up Group the changes allowing to reach internal consistency (left side of the canvas) and schedule them first The external activities that not require a stop in production are analogue to changes in the left side of the canvas that the customers do not perceive 2 - Convert Decrease number of changes requiring stopping/affecting the provision of business outcomes Convert internal into external operations when possible Segment and communicate with customers, test and validate assumption on client’s sample The internal activities that require a stop in production are analogue to changes in the right side of the canvas that are perceived by the customers. Test on customer’ samples allow to reduce the impact of changes to the provision of business outcome as perceived by the majority of the customers

3 - Streamline required for changes Reduce times Reduce the time required to perform operations

New offering (and the whole right part of the canvas) can be launched quickly given the internal consistency reached and the assumptions tested Early testing enables a safer and faster launch, backed by solid foundations. Assimilates information that validate assumptions on BM are analogous to reduce the time of operations

The SMED4BMC is a method providing guidelines for executing and manage business model change. At the same time, it enters in the LSA framework and going beyond its scope since it can be used in every process of business model change and not just in initial pivotal in early stages. The SMED4BMC fits particularly with digital new ventures that operate in a very dynamic context where changes are needed not only in the very early stages of startup. Change can even become a permanent state (Demil and Lecocq 2010), and this could be very likely true in the case of digital new ventures. However, long periods of co-existence between current and new model and organizational problems can arise (Chesbrough 2010). This multiple business models (MBMs) configuration is often seen as a risk that need to be managed (Massa and Tucci 2013). Nevertheless, the empirical evidence of the NexToMe case suggests that there are situations in which MBMs is identified and pursued as an opportunity. NexToMe shifts its focus from software to services provisioning without abandoning the previous activities. While a MBM may not be sustainable as startups scale and consolidate (Doz and Kosonen 2010, Massa and Tucci 2013), startups often inherently look for a MBM condition to experiment and scan for opportunities. Therefore, the coexistence of more than one business model may be perceived by entrepreneurs as a sort of ‘strategic fuzziness’ startups seek for to remain flexible (rather than a mere risk). Nonetheless, MBM strategic orchestration in a new venture needs to be supported by strategic tools enabling to seek and exploit opportunities while countering risks of misalignment, inconsistency, unclear direction and resources waste. SMED4BMC has been designed for supporting entrepreneur in flexible organization and its application in more structured companies should be coupled with more comprehensive actions.

The presented integrated framework goes in one direction: overcome the lack of methodologies in the extant literature for executing BMI. However, it is noteworthy point out that SMED4BMC helps the execution of a business model change process as potential source of innovation and not yet acknowledged as innovation process. The nature, the entity of the changes and the related impacts will determine the strategic and innovative profile of business model changes.

35

Conclusion and Future research

This study has its starting point in a fundamental assumption. The Lean Philosophy, already shifted from the manufacturing area and applied into the (entrepreneurial) Strategy world through an early approach (the Lean Startup), may play a significant role in advancing the Business model research in his theory and operative tools.

Indeed, it offers principles and methods able to improve the execution of processes, from a single and small task to the overall organizational philosophy. The research findings confirm the initial assumption by presenting: a) theoretical links or touchpoints between Lean Philosophy and Business Model Innovation; b) an integrated framework, as result of the common path for BM changes identified through the case studies and formalized adapting the Lean Manufacturing tools: SMED-ZERO and SMED.

The view of Business Model as potential source of innovation and the focus on the change process, preceding and basic for a potential innovation, allow to explicit the common factor shared among the extant literature on BMI: the changing perspective. Moreover, it is a link to the Lean Philosophy stream. Indeed, the contribution and the strategic impact made by the lean philosophy to the change process management is extremely relevant, see for instance SMED and SMED-ZERO.

Exploring the Lean Philosophy, in his theory and operative tools has been crucial to advance the Business Model concept through the changing perspective as well as to address also the second gap identified: the lack of methods supporting the execution of BMI. The integrated framework presented in this study goes in this direction, as result of the common path for BM changes identified through the case studies methodology and formalized by adapting the Lean Manufacturing tools SMED-ZERO and SMED. The SMED4BMC supports and smooth every Business Model change to customers’ eyes. At the same time, it enters in the LSA framework and goes beyond its scope since it can be used in every process of business model change and not just in initial pivotal in early stages. Given the high uncertainty intrinsic to entrepreneurship, this framework will not be a method for standardizing BM changes, but it will serve as guidelines along the process and to prepare the firm. It fits particularly for digital new ventures that operate in a very dynamic context where adaptation is needed not only in the very early stages of startup. However, it is noteworthy to point out that SMED4BMC helps the execution of a

36 business model change process as potential source of innovation and not

yet acknowledged as innovation process. The nature, the entity of the changes and the related impacts will determine the strategic and innovative profile of business model changes.

SMED4BMC has been designed for supporting entrepreneur in flexible organization and its application in more structured companies should be coupled with more comprehensive actions.

The author believes that studying and learning from new ventures will play a significant role in advancing the strategy field in the next years. The advancement of the Business Model Innovation research in his concept, through the changing perspective, and practical tools through the SMED4BMC, is only a small step ahead while opening several future direction research that need to be explored.

An interesting finding emerged from the case studies that deserve further investigation, and may open future research directions: the Multiple Business Model configuration (MBM). A MBM may not be sustainable as startups scale and consolidate (Doz and Kosonen 2010, Massa and Tucci 2013). However, the case NexToMe, shows that startups often inherently look for a MBM condition to experiment and scan for opportunities. The coexistence of more than one business model may be perceived by entrepreneurs as a sort of ‘strategic fuzziness’ startups seek for to remain flexible (rather than a mere risk).

Further research can mend this study’s limitations (related to the limited size and industry specificity of the theoretical sample and the observer bias characterizing qualitative methodologies) by validating and customizing the model in contexts different than the digital one where this research had its focus. Furthermore, this research witnesses the presence of large space for new studies that can leverage on Lean Philosophy for developing business strategy.

In the end, the author finds the dynamic complexity nature of the Business Model as valuable perspective (Massa and Tucci 2013) that may open to future research methodologies applied in this direction. For instance, applying the ‘system thinking’ approach (Senge and Sterman,1992; Sterman 2001) and simulation tools.