Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Università degli Studi di Siena Università degli Studi di Firenze Università di Pisa Phd Course

Political Science, European Politics and International Relations

Accademic Year

2015

/2018National Coordination Spaces

Models of coalition-building in EU Decision-Making

Author

Edoardo AmatoSupervisor

Prof. Andrea LippiContents

CONTENTS 1LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 5

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 6

INTRODUCTION 7

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK. IS THERE A SPACE FOR MEMBER STATES? 11

1. FROM EUROPEAN INTEGRATION PROCESS TO EU DECISION-MAKING. A THREE-LEVEL PERSPECTIVE 12

2. MEMBER STATES: THE FIRST LOBBYING ACTORS IN THE EUROPEAN CONTEXT? 14

3. NETWORK GOVERNANCE AND NATIONAL COORDINATION 18

4. A PRELIMINARY DEFINITION OF THE NATIONAL COORDINATION SPACE 20

4.1 THE NATIONAL ACTORS OF THE COMMUNITY IN BRUSSELS 24

4.2 INTEREST GROUPS WITHIN THE NSC 25

5. INTERNAL DYNAMICS OF COORDINATION 29

5.1 THE RELATIONAL PRACTICES AMONG DOMESTIC SOCIO-ECONOMIC GROUPS 29

5.2 THE RECURRENCE OF RELATIONAL PRACTICES AMONG NATIONAL POLITICAL ACTORS 31

5.3 THE RELATIONSHIPS AMONG ACTORS WITHIN THE NCS 32

6. THE SHARED AIM: PROTECTING NATIONAL INTERESTS 34

7. CONCLUSIVE REMARKS 37

METHODOLOGICAL CHAPTER 39

1. EPISTEMOLOGICAL PREMISES 40

2. RESEARCH DESIGN 41

3. DATA COLLECTION 43

3.1 A THREEFOLD FIELD WORK 44

3.2 CASE SELECTION 46

3.2.1 A MS more: The Netherlands 51

3.2.3 The Policy sectors under analysis 53

3.3 THE EXPERT SURVEY WITH REPRESENTATIVES OF INTEREST GROUPS 55

3.4 THE DIMENSIONS OF ANALYSIS 60

3.4.1 Quantity and qualities of national interactions 60

3.4.2 Aims and concretization of the national interactions 64

3.4.2.1 The general purposes 65

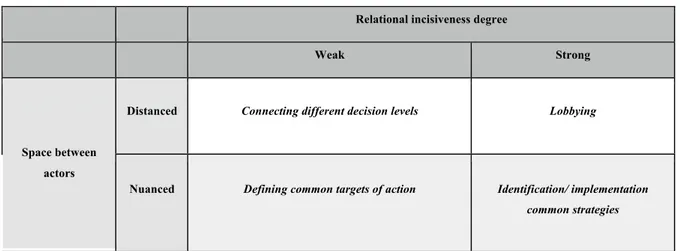

3.4.2.2 The relational concretization 67

3.4.3 The weight of nationality. 71

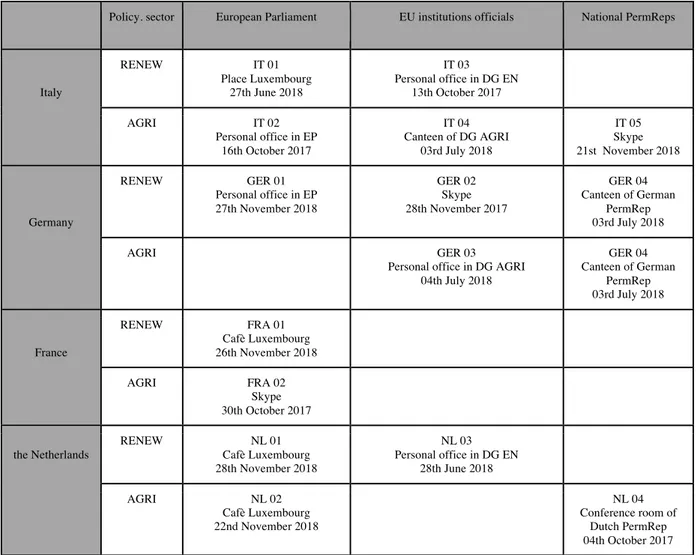

3.5 FOCUSED AND SEMI-STRUCTURED INTERVIEWS WITH POLITICAL-INSTITUTIONAL INTERLOCUTORS 74

4 THE RESEARCH QUESTION 79

5. DEALING WITH DATA 81

ANALYTICAL CHAPTER 84

1. SOCIOECONOMIC ACTORS: DOMESTIC INTEREST GROUPS 85

1.1 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS ABOUT THE NATIONAL SAMPLES 86

1.1.1 The national samples 87

1.1.2 Having an office in Brussels 89

1.1.3 The categories represented in the samples 91

1.1.4 The resources 99

1.1.4.1 Financial means 100

1.1.4.2 Cognitive resources 102

1.1.4.3 Relational resources 104

1.1.4.4 Resources and samples 107

1.2. THE WEIGHT OF NATIONAL RELATIONSHIPS IN EUROPEAN DECISIONS 110

1.2.1 National interactions 111

1.2.2 The dimension of national interactions 111

1.2.2.1 Individual relations with institutional actors 112

1.2.1.2 Individual relations with other groups 122

1.2.1.2.1 The heterogenous relationships 122

1.2.1.2.2 The homogenous relationships 126

1.2.1.3 National propensity to relationship 129

1.2.1.4 Relational Trend propensity 132

1.2.1.4.1 The internal composition of the (IRPI) and its variations 133

1.2.1.4.2 The internal composition of the (GRPI) and its variations 135

1.2.1.4.3 Comparison and trade-off between pairs of RPI 137

1.3 RELATIONAL PURPOSES IN EU DECISION MAKING 141

1.3.1 General Purposes 142

1.3.2.1 Italy 143

1.3.2.2 …Germany 145

1.3.2.3…France 147

1.3.2.4 …The Netherlands 149

1.3.3 Overview of aims 151

1.4 THE QUALITATIVE SIDE OF THE RELATIONAL SPHERE IN EU DECISION-MAKING PROCESS 156

1.4.1 Informality vs. Formality 156

1.4.2 Fluid vs. Structured 161

1.4.3 Collaborative or not? 164

1.4.4 Are these relations perceived reciprocal? 166

1.4.5 How much decisive are these relations? 169

1.4.6 National styles of relationships 173

1.5 RELATIONAL CONCRETIZATION: STYLES IN THE DEVELOPING OF THE RELATIONSHIPS 175

1.5.1 The meetings with sectoral national actors 176

1.5.2 The meetings with European sectoral actors 179

1.5.3 The meetings with national institutional actors 182

1.5.4 The meetings with national political actors active in Brussels 185

1.5.5 The meetings with national bureaucracy in Brussels 187

1.6 THE NATIONALITY MATTERS... 191

1.6.1 What do domestic groups tell us about nationality? 192

1.6.2 Something coordinated exists… 195

1.6.2.1 French domestic groups 196

1.6.2.2 Dutch domestic groups 199

1.6.2.3 Italian domestic groups 202

1.6.2.4 German domestic groups 207

1.6.3 Some general conclusions 212

2. THE POLITICAL-INSTITUTIONAL SIDE 214

2.1 GII experience and Italian space 214

2.2. National interests in Brussels: the institutional actors 218

2.3 The other part of the relationship in EU decision-making 219

2.4 The political staff of the European institutions: MEPs and Commissioners 221

2.5 The top positions of the Commission. Other political roles. 228

2.6 The administrative staff of the European institutions: the national officials in Europe 230

2.6.1 National officials in the Commission 232

2.6.2 National officials in the European Parliament and in other European institutions 238

2.6.3 An intergovernmental institution: The Council of the European Union 239

2.6.4 National diplomatic networks 239

2.6.4.1 Permanent Representations at the European Union 240

2.6.4.2 The national embassy to the Kingdom of Belgium 242

2.7 Institutional dynamics in the construction of coordination spaces 243

2.7.1 The Revolving Doors 244

2.7.2 The careers of European political and institutional actors 246

2.7.3 How many identities, how much loyalty? 251

2.7.4 Community building 255

CONCLUSIONS 260

REFERENCES 268

APPENDIX 281

List of abbreviations

ALDE Alliance of Liberals and Democrats of Europe CAP Common Agricultural Policy

DG ENE Directorate General for DG AGRI Directorate General for EP European Parliament

EPP European Popular Party EuroFED European Federation

GUE/NGL European United Left/Nordic Green Left ITRE Committee on Industry, Research and Energy MEP Member of the European Parliament

NGO Non-Governmental Organisation PERMREP Permanent representation S&D Socialists and Democrats

Verts/ALE the Greens/European Free Alliance TRofUE Transparency Register of European Union

Introduction

In 2013 I worked in Brussels for two months. It was my first work experience abroad. I was really excited. It was a traineeship and I dealt with a group which is involved in the creation of a network among several national realities. The mission of this organization is representing a national community and keeping connected different national actors which operate within the EU decision making process, by organizing events and initiatives. The coordination of national diversified interests in Brussels and the creation of a network of relations with European Institutions.

This group has promoted high-profile meetings with institutional and entrepreneurial spokesmen going through economic and business topics regarding Italy and Europe (GII). Or gala events and awards. During one of these events I organize with I could observe interesting dynamics of socialization. In December there was a Gala dinner, an informal occasion in which a lot of national representatives have dinner together as traditional friends do, by speaking about national business and aims. I was really interested in their relationship. In their exchanges. They seemed like old friends. Each person knew the others and there is a really easy-going situation. They were the result of frequent exchanges.

Therefore, I decided to write my thesis about this national system. I described the actors which compose it and hypothesized some reasons why this system could work together. This was the beginning of my curiosity about this topic. I have always been interested in lobbying world, but now I wanted to stress the topic of personal relationship which this kind of action relies on. So, I decided to focus my attention on a specific aspect of this decisional process and on its shapes within the European policy making. I would analyse the process of socialization, understanding in which national context this form of coordination develops itself. The European Union, or the Eurobubble, is a space of meetings among actors of decision making. People live together, sharing their professional life as well as their private habits.

In a decision-making context characterized by complexity and a high level of competition, the Member States, as the main actors in the decision-making process, should reconsider their action strategies. On the one hand, because they are increasingly forced to provide answers to sovereign references that expand into the national political debate; on the other hand, because they are not able to evade the logic of European competition (Panke 2012; Zielonka 2014).

The European Union shows a hybrid decision-making nature. Member States retain power over EU decisions but share it with new and different actors. Literature has often been divided about the role played by the actors within these processes, defining alternatively crucial member states or interest groups (Haas 1958; Lindberg 1963; Moravcsik 1991,1997; Héritier 1997).

My research would like to be inserted among those studies that relativize this theoretical dichotomy, showing how the process of European integration has deeply blurred the differences between these theoretical approaches and underlining both the permeability of these two actorial levels, and the presence of osmotic processes inside of the European dynamics able to relate the emanations in Brussels of the member states, the political-institutional actors with the socio-economic actors, such as the interest groups.

The member states, wanting to strengthen their position, seek to find and develop new forms of integrative action, national communities at the service of national representation. The research can be timely, given the recent attention to the danger that these dynamics of national coordination may in some cases degenerate into the legislator's capture practices, implemented mainly by large interest groups (as noted by Corporate Europe). The adopted perspective aims at identifying processes of repetition of practices among individuals who share nationality and who represent parts of the member state that can be involved in national coordination dynamics.

The complexity of the relationships that take place in the European decision-making process between national public-private actors can identify intermediate places for negotiating national interests. systemic dynamics that can favour action by member states, using a peaceful army of national actors who already participate in the decision-making process and who can take action to protect national interests. In observing the behaviour of national actors in Brussels, we could therefore witness the creation and sharing of practices and meanings that are tacit, known and shared on the basis of belonging to a common national, cultural and linguistic context.

Is it possible to identify artificial environments of national intermediation aimed at furthering national interests? Could be hypothesized that member states use a logic of influence based on cooperative and collaborative behaviours? How much do national cultural and linguistic aspects facilitate the shared practice within this space?

The research question is structured. A question to which I should progressively provide a series of answers with an incremental study oriented to capture informal dynamics. Dynamics that are difficult to identify. The objective of this work will be to investigate, and therefore to describe, the existence and functioning of new spaces of action useful for maximizing national intervention within a complex decision-making process. A process that member states find increasingly difficult to administer simply by using traditional tools.

The behavioural analysis of these coordination spaces, more or less obvious and voluntary, more or less structured, can be more easily understood using qualitative research methods, which allow to analyse in depth the boundaries and the interactions among the units that make up these networks. In other words, this work hypothesizes the presence of a sort of grey area within the European polity. this area would be characterized by high levels of informality, where relationships are created, and positions are shared, among the national actors active in Brussels. An intermediate negotiation locus, that connect furtherly the member states with the supranational policy-making, in which

linguistic-cultural sharing acts as a glue, pooling the national political-institutional dimension with that of domestic interest groups. A place where the reiteration of shared practices generates processes of creation of new understandings, even influencing the process of renegotiation of national interests. They are quiescent relational environments that can be activated in the presence of specific policy processes or in specific sectors. Probably there will be a difference between activation and presence. Even if the national actors involved are present, they could group and organize adopting several different conformations. The different degrees of coordination might lie both in organizational/structural features and in the way in which this process is managed by the members. So, these are variable spaces, with different degree of coordination.

The European decision-making context is enriched daily by new political actors from different backgrounds, national and functional, who participate in European policy-making, attempting to respond to their goals. The presence of these national networks can be hypothesized, due to the need of member states to find new integrative forms of protection of their national interests.

The recourse to indirect and informal paths of influence can increase the relevance of member states within the decision-making process. The state should be considered as a whole, as a unitary actor, but even as the sum of its component parts, subnational components that have now achieved autonomy of access to the decision-making process. Components that on the one hand the member state seeks to

hetero-manage, where possible in order not to dissipate the surplus of potential of common action in

the European negotiation, and on the other can coordinate from the bottom, taking advantage of the usual practices of relationship and exchange between political-institutional actors and socio-economic actors.

The first part of the thesis deals with the issues related to ontology, epistemology and research methodology. In the first chapter the theoretical framework within which the formation process of these national coordination spaces is developed, which actors can compose it and how the functioning dynamics can be imagined will be addressed. The second chapter is dedicated to the methodology used. Both the research design and the methods used to collect and analyse the data will be illustrated here. The second part is dedicated to the analysis of the data collected, to understand the role played by domestic interest groups and the current forms of direct and indirect representation of member states. In the third chapter the relational practices of interest groups will be analysed. Through the study of the dataset, constructed by gathering the answers provided by the interest groups to the survey, a description of the intensity and the methods through which the meetings take place and take shape will be proposed. Finally, in the fourth chapter, thanks to the analysis of the semi-structured interviews, the institutional actors will indicate how and through the adoption of which practices the national coordination is realized.

Theoretical framework. Is there a space for member states?

A space in the European decision-making context for the presence, in the acting of the member states, of new forms of strategic differentiation can be based on some contributions on the European Union (EU) and on the development and characteristics of the European decision-making process.

In order to introduce the argument in analysis, at least three theoretical levels of analysis can be distinguished. As suggested by Peterson and Bomberg (1999), the understanding of the functioning of the European system needs to a theoretical approach to multiple levels. Multilevel actions require the use of differentiated theory (Rosamond 2000).

A first level, called super systemic, concerns the interpretation of the process of integration of the European Union. The second level, defined as systemic, is dedicated to the functioning and development of the institutional system of EU. Finally, the third theoretical level, the sectoral one, is focused on the individual European decision-making processes and on how these are formed over time within the different sectors. These three levels of analysis, while dealing with different aspects, contribute to the construction of the process of understanding of European dynamics. Despite studying these areas separately, we should take into account how the characteristic aspects of each field of study can influence the subsequent ones, and vice versa.

The understanding of the object of the research presented here develops, starting from this third level. Being focused only on the explanations of some aspects of the European phenomenon, it could be included in what are called middle-range theories (Rosamond 2000). Specifically, the interest here is oriented to bottom-up processes of national coordination relative to the European decision-making process and to the dynamics that characterize it. Dynamics that take place at the micro systemic level and that can be included in the social constructivist approach to the EU.

Goal, to identify interaction dynamics based on shared practices, cultural and identity aspects or common understanding that characterize the progress of the European integration process, thus giving particular emphasis to the relationships among the single individuals that make up the networks of actors operating in the sectors of policy.

In the next paragraph I will propose a brief excursus of these theoretical levels, declined according to those aspects that can characterize, and maybe influence, both the European policy-making process and consequently the interaction dynamics that this work wants to bring out.

1. From European integration process to EU decision-making. A three-level

perspective

For a long time the literature on the European Union has been divided on the nature of both of the European integration process and of decision-making, emphasizing the presence of a situation of profound contrast between those who are the different levels of government within the European political system and, consequently, between the actors who represent. A process understood as the stratification of decisions taken over time within the EU, with particular attention to the actors who participated in the structuring of the European plant.

First of all, we should refer to the great debate that has characterized literature and studies on EU, the dualism between the grand theories on European process of integration1. Focusing on the position of the actors involved in the decision-making processes, intergovernmental theories2 and supra/neo-functionalist theories attempted to describe their roles and interactions, often clashing. The first ones underlining the existence of a strong intergovernmental bargaining (Hoffmann 1966; Moravcsik 1991, 1993, 1997, 1998; Héritier 1997), the latter opting for the hypothesis of a competitive process between a plurality of institutional, economic and social elites, directly at European level (Haas 1958; 1971; Lindberg 1963; Schmitter 1971). The former defending the primacy of individual member states, the latter emphasizing the centrality of a framework of directly composting actors at European level, both institutional and socio-economic.

According to these grand theories, the legitimacy of EU decisions therefore fluctuates between a formula linked to the definition of negotiating interests in an exclusively national context, which is only subsequently transferred to the European decision-making context, and one based on the output legitimacy, the efficiency of decisions taken by functionaries ganglia, members of a supranational organization (Moravscik 1997; Scharpf 1997; Reich 1997).

As mentioned, there are also middle-range theories, more oriented towards understanding the functioning of the European political system. In particular, a series of studies on European decision-making and the policy analysis of the European context (W. Wallace/H.Wallace/C. Webb 1983; Lodge 1983).

Among these, the institutionalism, in its various forms3, places institutions at the centre of the European political process. Particularly interesting for the development of this work is the sociological approach that marks the role of social interactions, with institutions in particular, in

1 These are theories deriving from the IR studies legacy, dealing especially with the relationships among states.

2 Here, for the sake of brevity, both the first institutional intergovernmental model and liberal intergovernmentalism, the two

main theoretical contributions of Moravcsik, are brought together.

3 There are three contributions that vary in the role designed and intended for institutions (Jupille / Caporaso 1999). In addition

to the sociological institutionalism, previously mentioned, the first declination, called i. of rational choice, suggests that the institutions and preferences of the actors can influence the process of policy making (Tsebelis 1994; Garrett 1995); Historical i. sees in the institutions a factor that can influence the preferences of the actors over time, re inserting the concept of path

generating the identities of the actors, providing «cognitive scripts, the categories and models indispensable for action (Hall/Taylor 1996, p. 948) ».

Among the middle-range theoretical approaches there are those oriented to the analysis of European governance that emerged over time. The alternative approaches for the grand theories do not allow to fully grasp the complexity and the richness of interactions that characterize the European decision-making process, a context that shows the presence of more linkages among actors coming from different decisional levels (Hix 1994; Rosamond 2000; Kassim 2004).

For this reason, the presence and functioning of the NCS develops from the theoretical perspective of multi-level governance (MLG), which assumes the presence of a permeable structure composed of several communicating levels supranational, national and local (Marks/Hooge 2003). According to this perspective, both supranational and national levels are important arenas in the work of influencing European decision-making. Furthermore, the link between decision-making levels facilitates the direct activation of economic and social actors, such as domestic interest groups (Marks et al 1996; Scharpf 1997). This differentiated participation, by nature and origin, means that (1) the centres of decision-making should be understood as closely connected, (2) the actors' work not limited to a single decision-making level and (3) the impossibility of defining the pre-eminence of a specific actor/level (Marks 1993). The decision-making process should be understood as a continuous flow of interaction within which the participation of each subject is diversified and multifaceted. Within this flow the boundaries of these decision-making levels are not well defined due to the decision circuits, thus giving rise to intermediate spaces, grey areas of interchange and further relationship (Bache/Flanders 2004).

Following the theoretical advice suggested by Peterson, that of proceeding with a multi-level analysis, I am now introducing a further level of analysis, the sectoral one. Given the number of relationships and links between decision-making levels the reconstruction of the dynamics underlying European decision-making can be very difficult. A difficulty exacerbated by the wide decision-making capacity of the European Union. The description of the relationships becomes simpler even integrating a longitudinal logic, distinguishing the policy sector of intervention (Sandholtz 1992; Greenwood/Ronit 1994; Falkner 2000).

These are some of the characteristics of the European decision-making process (Peterson 2004) which require the inclusion of a further analysis logic:

1. differentiation between sectors in terms of actors and rules; 2. absence of hierarchy and interaction between public-private actors; 3. widespread technicality in the production of policies;

4. formulation phase of the very long policy proposal characterized by the participation of diversified actors in the negotiation phase;

Considering European governance as structured on several levels, the specific policy networks established, understood as «the structural relations, the interdependence and the dynamics between actors (Schneider 1988)», must be attributed to a process of European integration in continuous evolution, which has therefore strongly influenced the characteristics, differentiating them, of the various policy networks (Börzel 1997). The use of this theoretical approach here highlights the centrality of the relational sphere in the formulation of the decision. The networks that are formed describe horizontal relationships among different actors, political and institutional actors and socio-economic interests, and who participate in the decision-making process of the individual policy area. In the European case, private actors create different systems of relationships, including interpersonal ones, within singular policy processes (Wilks/Wright 1987). Taking into consideration the institutional actors that make up a given policy network, we know that they will have inter-institutional relations, therefore horizontal at European level, but will also come into contact with national and local institutional levels (Kassim 2004). The interest groups, the other socio-economic actors involved, differ between European interest groups and domestic interest groups. If the former act at the European level only as aggregators of national realities, the latter from the theoretical perspective of the MLG act in the national and European arenas (Balme/Chabanet 2002; Saurugger 2005).

Once we have analysed the main theories concerning integration and governance of the European Union, in the next few paragraphs we will focus on the micro-theoretical perspective we want to adopt.

2. Member states: the first lobbying actors in the European context?

The most interesting aspect of constructivist approaches was to analyse European integration as a process, therefore analysing its dynamism in the transition from a «bargaining regime to a polity (Christiansen, Jorgensen, Wiener 2001, p.11) ». A process in which a series of interactions among social agents have given way to the construction of common practices, shared cultural understandings, institutions and norms in the European sphere (Risse 2004).

As already mentioned, both the grand theories and the middle-range ones related to governance have the merit of grasping some characteristic aspects of the European decision-making context. The evolutionary process of the EU shows a sort of temporal block, «a lack of correspondence between (neo-functionalist) theory of integration and the unfolding reality of European integration (Rosamond 2000, p.119) ».

Perhaps the most obvious aspect is probably the maintaining of the centrality of the member state as actor of the decision-making process (Moravsick 1993, 1998). The literature has repeatedly addressed the issue of the evolution (weakening-strengthening) of the role of member states in the current

European decision-making context (Milward 1992; Moravscik 1994). The relevance of this actor in the EU decision-making process has often been investigated in its forms of direct influence, without dwelling on the informal and indirect aspects of national representation. As suggested by the picture above, at least two different forms of national action can be identified within the European decision-making context:

• direct and formal participation • informal direct lobbying

Pic. 1 Forms of influence of MSs in EU decision-making

First of all, the direct and formal participation. Each member state can make its own contribution by participating in the segment of the decision-making process that is its responsibility within the two EU intergovernmental institutions. Among the forms of direct participation there are three different forms of national representation that can be adopted (Richardson/Christiansen 2005):

1. ministerial

2. action based on the work of heads of state and/or government 3. administrative action.

The first type of direct participation is observed in the dynamics that orbit around the Council, an intergovernmental institution in which national governments actively seek to achieve their goals, even clashing with the interests of other member states. Within the work carried out by the Council, each EU Member State is represented by members of its national government. The different sectoral sessions in which the Council meets, indeed, involve the national ministers in charge. The European Council is the intergovernmental institution in which national structural interests are mainly taken into consideration and protected. The second type of national direct participation is so realized. The European Council, composed of the Heads of State and Government of the member states, gives representation to national instances within the European negotiations.

Finally, direct participation can also take place administratively. Over the last few years the administrative apparatus that manages the work of Council has grown numerically. Alongside the figure of the general secretary, top of the administrative structure, the Permanent Representatives Committee (COREPER) has carved out an important role, within which the dynamic of national representation is carried out by the national delegates (de Zwann 1995).

The second kind of action is the informal direct lobbying. Indeed, in addition to this form of participation in European negotiations, member states have created several mechanisms for monitoring the behaviour of EU institutions within the European decision-making process. At European level there is an institutional partnership for the creation of the decision, a characteristic that confirms the multiplicity of institutional access points to the European PM. Member states, adopting the strategies typical of interest groups, can adapt their action and focus on specific institutional targets, differentiating their strategy (Streeck/Schmitter 1993; Marks et al. 1996; Panke 2012). Indeed, they are real subjects that further special interests, the all-encompassing national interest. These interests often concern policies of a more general scope, those that concern the functioning of the entire EU apparatus and those that concern the direct effects that these policies create within individual national realities. To fulfil this objective of national representation, each member state can decide to control the whole European decision-making process, trying to approach and relate to all the levels of European decision-making involved. Member states can informally influence EU affairs using different paths of action. For instance, they can lobby the European Commission in the pre-proposed phase of the legislative process; they can otherwise control the impact of voting within the European Parliament or use the comitology committees to monitor the policy implementation phase (Christiansen 2005; Klüver 2011; Panke 2012).

The adoption of these informal mechanisms is necessary due to the lack of formal relevance of the member state, understood as a single actor, within the stages of the decision-making process concerning the Commission and the European Parliament. As well as to strengthen the position in the

trilogue meetings, one of the last phases of the co-decision procedure (Panke 2012).

Anyway, we must not underestimate the ability of states, intended as unitary subjects, to maintain a role in relations and negotiations within the EU decision-making process even adopting new ways to

influence the final output (Nugent 1999; Panke 2012). Indeed, the current role of the member states within the European decision-making context is changing. The evolution of the European integration process would suggest a strategic change of the role of the member state. This actor had to change its approach and to differentiate its strategies both in order to answer to the EU PM transformations, and to respond to the inputs caused by the economic crisis (Grande 1994; Jachtenfuchs 1995; Rhodes 1996).

Moreover, a further reason for this strategic transformation would reside in the need to respond to growing internal requests/pressures to recover the surrendered sovereignty. Therefore, it would be an answer to the processes of renationalisation of the European decision-making process.

To conclude, here the NCS has been hypothesized as a relationship system able of involving national actors in Brussels. This would be a type of intervention that integrates the classic direct perspectives of national lobbing put in place by national governments. A new and integrative approach of MS that may be considered significant because of the partial removal from a purely intergovernmental type of negotiation model, as national governments today are unable to monopolize policy-making power, which would instead be widely dispersed among many public-private actors along different European decision-making levels (Börzel 1997; Kassim 2004).

Once observed these two kinds of MS’ actions it would be interesting even discover if member state has developed other new forms of national representation, in particular if the MS has the ability to manage even those dynamics that concern the horizontal relationships that take place in the EU.

3. Network governance and national coordination

«By adding a third or fourth level of governance to the political systems of the member states, the complexity, dynamics and diversity of decision-making, already typical for modern societies, has increased considerably, increasing the need for non-hierarchical coordination of public actors and private at all levels of government within policy networks (Börzel 1997, p.13)».

The previous paragraph has been dedicated to a brief overview of the set of actions that each MS may adopt in order to influence the EU PM. As said, usually the classical theories dealt with the members states as unitary actors. I would like to underline the role played by their components, especially those that work daily in Brussels. For that reason, this work is focused on the national actors and their relationships within the EU decision-making. This attention to a meso-micro level of analysis allows me to grasp (1) the role played by the national components and the dynamics that stand behind their behaviours, (2) the contribution of socio-economic actors in shaping the national interests, (3) the existence of integrative and new ways to further national positions in the decision-making process. The member state needs to coordinate its component parts, both within national borders and in the European context, in order to try to define a national position to be maintained in the European negotiations. Leaving aside the national dimension, the coordination actions are difficult in Europe both because of the presence of a high number of actors operating in the decision-making arena, and because of the complex and disaggregated decision-making procedure. Furthermore, some traditional forms of coordination and aggregation of interests typical of national contexts, such as parties or professional networks, are weak in Europe (Wright 1996).

The member state may use its need to coordinate their internal parts as an integrative tool in order to influence the European PM (vertical perspective of action), as well as these national components may coordinate their actions more autonomously, following a perspective of action based on horizontal set of relationships. In other words, the national components can be moved from above, or instead following a bottom-up (or horizontal) logic.

Starting from the first case, the coordinating actions are driven by the MS and the main goal is creating a situation in which the decision-making output, and subsequently the outcomes, is quite similar (or not too different) from initial national preferences. As said, these preferences can arise from an effort of coordination that follows a top-down logic, so (1) the goal is to speak in Brussels

with one voice, (2) the preferences, according to the intergovernmental logic, selected within national

boundaries, and (3) the actors coordinated in a set of joint actions. This top-down logic can even be oriented to the simple soft function of transmission belt between the two decision levels (Kassim/Peters/Wright 2000). So, the dynamics of definition that occur within national boundaries remain crucial, because they allow to MS to outline their positions.

Moving to the second case, national coordination can also take bottom-up arrangements. All the national actors who crowd the European arena along the tortuous decision-making process are daily involved in a series of mutual relationships, which can generate internal processes of consultation and

negotiation. Hence the national public and private actors may coordinate their own actions by exploiting the spreading of horizontal relationships.

This second case highlights how the MS may exploit characteristic features of the European PM in order to coordinate its components. The EU decision-making context presents all the typical characteristics and dynamics that favour the development of (policy) network governance (Marin/Mayntz, 1991).

« [...] 1. a relatively stable horizontal articulation of interdependent, but operationally autonomous actors; 2. who interact through negotiations; 3. which take place within a regulative, normative, cognitive and imaginary framework; 4. that is self-regulating within limits set by external agencies; and 5. which contributes to the production of public purpose (Sorensen/Torfing, p.9)».

This definition frames a governance situation that well represents the management of the production of public policies in the European context (Fawcett/Daugbjerg 2012). Many autonomous subjects who compete with each other and are involved in decision-making processes characterized by a high degree of technical competence necessary to elaborate the decision. Different levels and types of actors that interact with each other and a long formulation process that can be influenced in several moments.

«Governance networks [...], can take many different empirical forms depending on the political, institutional and discursive context in which they emerge. They might be dominated by loose and informal contacts, but they can also be tight and formal. They can be intraorganizational or interorganizational; self-grown or initiated from above; open or closed; short-lived or permanent; and have a sector-specific or society-wide scope (ibidem p.16) ».

Therefore, in the European context the creation of differentiated networks seems to be a widespread phenomenon, even thanks to the numerous sets of relationships that are created every day.

The policy networks are characterized by the co-presence of different actors with different interests to defend and a contextual situation that presents interdependence of resources, the object of the research starts instead from slightly different theoretical premises. Other models of network governance may exist as a «[...] relatively institutionalized field of interaction between interested and affected actors that are integrated into a community defined by common norms and perceptions (ibidem p.19) ». These dynamics of coordination often rely on informality. The literature on the relations between public-private actors has not enough treated this type of informal dynamics, that are very widespread in Brussels (Averyt 1977; Streeck/Schmitter 1991; Juncos/Pomorska 2006).

To sum up, the aspects addressed may be useful in order to introduce a new concept that I would like to deal with. Thanks to their contribution we can change the perspective with which we usually try to speak about the member states in the EU decision-making. Hence, a first definition may underline how the National Coordination Space may be considered the area in which both these forms of coordination are realized.

4. A preliminary definition of the National Coordination Space

So, what is an NCS? Which are the characteristic aspects? The nature of the NCS, to be captured in depth, should be subjected to a patient work of building the boundaries of these coordination spaces. The existence of these national forms of coordination can sometimes be confirmed by following a

rationalist approach, based therefore on the sense of belonging of the actors themselves and the set of

cognitive and symbolic connotations that follow; more often it is realized thanks to the nominalist contribution of the analyst, which defines the boundaries of the system.

At a preliminary stage, the balance leans towards the second approach. Indeed, I propose as boundaries to circumscribe the concept of NCS the nationality and the common linguistic and cultural sharing. The processes of socialization that take place within the EU policy-making between such different actors are differentiated and multiple. In our case, beside a strictly sectorial logic and institutional belonging, the actors involved follow national connection dynamics. In other words, there are sub-networks, or alternative networks, which move following nationality logic.

The first step is providing with a preliminary definition of the national coordination system concept.

The vast range of relational practices that occur among actors with different backgrounds, but who share the same nationality, within the EU decision making and that are aimed primarily at coordinating some of their actions in order to further national common interests. These NCS generate both an inward effect, by actuating a process of sharing and creation of common understandings among the involved actors, and an outward one, by promoting dynamics of reshaping of the national positions of MS.

First of all, something about such use of this terminology. We have already talked about the reason why I chose the national coordination expression, instead nothing was told about the use of the term

space. I opted for that, because I wanted to indicate something circumscribed. I am considering the

interactions among national actors active in Brussels, so highlighting that there is even a sort of overlapping with a geographical (physical) place. The definition of social space takes in consideration something different to the physical space, something more and beyond. This term may state

«The universe of meaningful relationships between individuals, groups, categories, social strata and classes, cultural elements [as translated by the author] (Gallino 1978, p.664) ».

This term allows me to concern an area that is created among those actors that share nationality. An area within which the actors develop a series of interactions that over the time structure national relational practices. Within this area there are only those actors who share national common understandings.

This NCS may be considered as a decision arena. The recurrence of this relational exchanges produces two effects. One on the internal dynamics, and the other externally. These two effects are really interrelated, and they nourish one another. The relationships that occur within this space, as we will see in the following paragraphs, may change both the individual positions of components and the MS one. In other words, the interactions may generate a process of reshaping of the national positions, individual and as MS.

On one side there is an internal dynamic. From a micro-sociological point of view, the exchanges between individuals involved in NCS are based on common understandings and practices. This process of sharing may lead to the creation of new common understandings. These common aspects generate common practices of interactions, so showing us how this internal process is circular. In so doing, they contribute to an internal process of formation of new mixed identities (Risse 2004). These are able to change the individual preferences, by providing with new understandings and the whole of (new) practices that the actors involved use to relate one each other. A sort of shared repertoire of actions/interactions that are adopted with the aim of completing a common enterprise, the furthering of national interests (Wenger 1998). In other words, the connection is due to the fact that within this space of socialization, the creation of new identities and meanings is based on the coexistence of several common aspects, as the language and the shared culture which represent resources for the community itself. These (new) understandings, once internalized, generate a process of formation of new practices, of interaction modalities.

On the other, there is instead a dynamic relative to the external side of the NCS. This dynamic is partially subsequent to the previous one. As said the NCS may be considered as an integrative tool for the MS both because it ideally acts to connect all the national components and to keep them together during the policy-making process and because it can be considered as a sort of national mediation area. Indeed, from the perspective of MS, this national tool could be useful for the reshaping of representation of member state and to influence EU PM. This could be considered as a form of

system-country extension of the national sphere that operates in an international negotiating context.

Following the logic of the search for compromise, of adaptation among the individual positions of the actors, the NCS may provide with a new (re-shape) national position. In other words, the involvement within this space of all the components (political, institutional and socio-economic) it allows the MS to create a sort of intermediate negotiation directly in the EU PM. This process, as said, would start from (and thanks to) the individual interactions and relational practices among the actors of national community in Brussels. Obviously, in this latter dynamic we should take in consideration event the vertical solicitations coming from the national boundaries (top down perspective).

This space may be interpreted differently by the MS and it may assume different forms. Basing on my direct experience I observed that some countries adopt this tool in order to create something national, but its structure may change according to each country specific context, even adopting very different shapes.

Not all EU countries have the same capacity to adopt lobbying activities aimed at protecting their interests (Panke, 2010). This could certainly also apply to NCS, whose action could be influenced by several factors. On the one side, there are main factors directly related to the composition of these forms of national coordination and representation: (1) the quantity and quality of resources available to the actors; (2) some institutional features of national political systems; (3) the level of Europeanization of the actors that make up the network. On the other one, there are even exogenous aspects to the NCS that could have a reverberation on training and functioning, such as policy area, issues analysed and characteristics of European decision-making, (Beyers 2002; Ringquist et al., 2003; Slapin 2008; Klüver 2012).

This space can be considered even as a national network. Borrowing the definition from organizational studies, taking in account even a micro perspective, the idea of network is here understood both as «the network of interpersonal relationships within the organization and to describe the relational structure constituted by the consolidation of exchange relations between different institutional units (Lomi 1991, p. 21)». So, this is a social space, an abstract place where the social relations occur and take shape through process of rapprochement/separation among the actors involved (von Wiese, 1955). These relationships have a specific shape. As said, they structure themselves around the shared nationality, thanks to the common language of the actors involved. The composition is varied, because the actors belong to different backgrounds, but their relationships occur in a very collaborative way. In our case they know their need of resources’ exchange in order to make the network more competitive in reaching a common aim. In other words, the existence of these networks is indeed substantiated in the exchange and interdependence relationship that exists between the actors of different nature involved, despite their peculiar interests to be protected. Among the actors these reciprocal ties are created due to the need, the possession and the reciprocal exchange both of qualified information and of symbolic and political resources (Marin 1990; Kenis/Scheider 1991; Marin/Mayntz 1991; Kooiman 1993; Mayntz 1994; March/Olsen 1995).

Moreover, this abstract space presents features as a sort of national community, based on reciprocity, informal ties and the commitment among actors involved. This is a micro-sociological perspective, more focused on the daily ties of individuals involved. The overlap between decision and individuals’ places, typical of the Eurobubble, generates deeper ties among people, especially if they already share some cultural and linguistic aspects.

The informality of many meetings moments (sport, dinner gala, school) can spread a sense of belonging to defined community. It also worth noting that there are even institutional structures or structured organizations that may facilitate this process of exchange and sharing that is at the basis of the community4. In other words, the national individuals have many informal and non-working moments that make deeper the sense of membership to a national community.

To conclude and sum up, here I reported briefly the main characteristic features of NCS just mentioned:

• The presence of differentiated national actors that compose a national structure. Public and private actors coming from the same MS that work in the EU decision-making.

• The recurrence of relational practices.

o Horizontal and not-hierarchical relationships based on informality and resources exchanges. Non-hierarchical relationships between states and non-public actors, both public and private, that interact in a process of continuous negotiation attempting to protect specific interests, even with differentiated sets of resources and levels of authority (Mayntz 1993b: 10f; Scharpf 1994; March/Olsen 1995; Scott 1995).

o Cooperative environment - Cooperative dynamics. The participants, in order to obtain a shared interest, adopt cooperative methods typical of the European context where the interdependence of resources more rarely turns into a conflict (Voltolini 2011, 2013).

o Common language, culture and understandings. The unifying criterion of these coordination systems is therefore neither the primary objective of the lobbying action, nor the sector in which the actors operate. The space is composed of the actors and their relationships, but another crucial aspect are the meaning systems, as the language and the cultural features (Sorokin 1927, 1928).

• Shared aim a National interest…in development. A process of negotiation and renegotiation of national positions within the space. The sharing among national actors during the relational dynamics generates changes within the individual position of involved actors and consequently may generate shapes of coordination around new national positions. A space in process or in movement.

In the following paragraphs these aspects will be addressed more in depth, explaining the theoretical approaches that makes these aspects crucial in the effort of NCS definition.

4.1 The national actors of the community in Brussels

The first point concerns the presence of a certain national structure, more precisely of a set of actors that can function as a basis for the creation of more or less stable relationships within this network. These networks are made up of all the formal, and especially informal, relationships and contacts among the various national actors active in Brussels. As already mentioned, there is a complex system of exchanges and interactions among these actors, which have different nature and status. This situation is given by the overlap, typical of the Eurobubble, between the decision-making community and the social community. Given that the places, formal and otherwise, of the decision and the places of the communities often coincide, functional relations are intertwined with personal relationships (Averyt 1977; Streeck/Schmitter 1991; Juncos/Pomorska 2006). The structure of these systems would be characterized on the one hand by diversity and on the other by partiality. Different actors play different roles and functions within the European decision-making process, but all parties are necessary to fulfil the main objective of these coordination systems. The behavioural mechanism is complex and requires the commitment of all the parties involved, precisely because of the functional differentiation they exercise for the purpose of developing the coordination system itself (Wenger 1998). Having said that, now we reach the heart of the actors’ dimension. The European decision-making system provides for the presence, also physical, of actors coming from the 27 (28) national contexts. Each member state can count on a national milieu composed of political actors, institutional actors and socio-economic actors.

The first group, the national political chain, is made up of the set of offices, elective or nomination, which play a role in the European decision-making process. The national political actors are first and foremost the national members of the European Parliament. European political parties are organizations that are still unlikely to act independently of their national counterparts because they are unable to coagulate the consensus. The classical logic of political representation of traditional parties among European parliamentarians seems to be accompanied by a kind of national loyalty. The election within national political contexts contributes to not strengthening a partisanship at European level (Bardi/Calossi 2010; Calossi 2011). The national political milieu can also count on top figures within the European Commission DGs and parliamentary assistants.

Alongside this defined political staff there is a second group of actors, the European bureaucracy. Personnel from the different national contexts of the EU who work in the administrative staff of the institutions. Civil servants performing administrative duties within the Commission, the European Parliament and both the Councils. This category also includes officials working within permanent representations at the EU, where the logic of national representation is more observable, and the administrators engaged in representative offices of sub-state institutions, in particular regional ones. The latter, it should be remembered, can also operate as stakeholders (Profeti 2003). Furthermore, for the purposes of research, this group of national officials should also include the staff at the service of the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the various agencies and bodies that orbit the Commission.

The two first groups before analysed, in addition to carrying out a national institutional lobbying action, operate simultaneously with the third group component of the structure, the socioeconomic actors. Particular attention should be paid to this third category.

4.2 Interest groups within the NSC

The third segment of the national structure is composed of the socio-economic actors, all those domestic interest groups that attempt to influence European PM directly.

The thesis takes into consideration all those groups of domestic interest that act both nationally, trying to influence the national decision-making process with direct action, and directly at European level, adopting a dynamic of externalization of their own interest. Those groups that have outsourced their action to Brussels to overcome the difficulties of sectoral representation suffered by the Eurogroups (Balme/Chabanet 2002; Saurugger 2005).

Up until the 1990s Eurogroups were the most common form of participation in European decision-making for economic and social interests. Domestic interest groups entrusted the protection of their own interests within the European context almost exclusively to their horizontal and sectoral representation. For many groups it was a mediated participation in the European decision-making

process. For others, a limited number was a tool that integrated direct representation with the European decision maker (Balme/Chabanet 2002; Saurugger 2005; Eising 2007; Guéguen 2007). In the course of their ascent, the widespread presence, within these Eurogroups, of domestic interest groups that gave priority to a national logic ended up increasing the difficulties in the internal negotiation processes between the different national positions that made up the membership. The EU enlargement process has further increased the level of internal heterogeneity of these organizations, which have had to represent an increasingly complex mix of national interests. An enlargement that has increasingly brought out a logic of representation of the lowest common denominator, thus negatively influencing the capacity of these representation tools (Balme/Chabanet 2002; Saurugger 2005; Eising 2007; Guéguen 2007). These factors, together with the increasing skills that are delegated to the European level and the consequent increase in competition in the European decision-making context, have accelerated the growth of the direct action of domestic groups within the decision-making arena (eg Mazey, J. Richardson 1993; Greenwood 2007; Klüver 2010). Domestic interest groups that have strengthened their direct activity, without however possessing some of the Eurogroup's own resources. The initial success of the Eurogroups was in fact attributable to the ability to provide political resources. This type of group, counting on a legitimacy given by the number of subjects that the position assumed represented, had greater capacity to collect this type of resources, compared to domestic groups, whose action could only count on the consent relative to the membership of the groups themselves (Balme/Chabanet 2002; Saurugger 2005; Eising 2007; Guéguen 2007).

For this reason, domestic groups, while not completely abandoning their participation within the Eurogroups, have deemed it necessary to have to expand their action options, investing in new strategies that could expand the political resources available to them.

Limiting ourselves to the observation of this type of domestic interest groups is due to logical reasons relating to national representation. Analysing the groups that mostly limit their action at national level is not crucial to describe the national coordination systems; the other groups excluded from our study, the Eurogroups, follow the logic of supranational representation.

The thesis will put this kind of actors to the fore for four different reasons, here briefly reported. Firstly, I am dealing with MSs as lobbying actors. Before I described in which ways the member state may influence the EU PM in order to protect its set of claimed national interest. In other words, I am studying those practices that the MS borrow from the interest groups. This national behaviour has been already studied by the literature considering MS in its entirety, as unitary actors. I stressed the fact that the MS has a national structure active in Brussels, so it is important to focus even on the individual components.

Secondly, the domestic interest groups represent the national civil society. Interest groups active in Europe have been recognized as the driving force for civil society participation in the formulation of the decision. The interest groups remain the non-institutional actor that guides the process of

formulating the European decision, determining the contents of the policy-making process. They can access the decision-making process by bypassing political parties, which do not exercise the function of gatekeepers unlike national contexts. The European party system indeed can be defined as pre-party, because the structure of the competition for the creation and control of the European executive is not based on logics that see the participation of the European parties (Bardi/Calossi 2010, 2011). The interest groups become the subjects that can facilitate a form of mediated participation in the decision-making process and consequently would be able to provide democratic legitimacy to the decisions themselves adopted by the EU. In a context such as the European one, where the main decision makers do not enjoy electoral legitimacy, interest groups can act as links, supplying inputs from civil society and thus giving an answer, albeit partial, to accusations of democratic deficit put forward against of the EU (Kohler-Koch/Finke 2007). Therefore, within the European political system, lobbying is a tool that tends to replace and not support political representation.

The domestic IGs within the NCS have to make emerge the position of the national civil society. Thus, domestic groups exploiting the NCS could strengthen the political role of connection between national civil society and European decision makers, proposing a further response to the question of the legitimacy of European decisions to which the classical theoretical approaches do not know how to give a clear answer5.

The recognition of the presence of the NCS could dilute the aforementioned issue, providing new keys of interpretation. The process of national socialization could produce new shared meanings, by creating exchanges between public-private subjects on the basis of a common language and a shared culture. Thus, starting from an initial position provided by the national government, within the NCS the reformulation of national positions would develop according to a dynamic of counter-balancing between the positions of the actors involved in the socialization process. A position of autonomy of European officials would be mitigated by the positions of the other non-institutional national actors involved and would therefore be the result of negotiations with positions of actors, groups of domestic interest, which have a capacity for representation and therefore find a legitimacy of their positions. Thanks to the role of domestic IGs the NCS would also be able to provide new interpretations of the problems of democratic legitimacy which the EU decision-making process suffers, formulating internal positions that are the result of compromise, but which enjoy support because they are representative of the different souls that make up a country system.

Thirdly, domestic interest groups may connect the levels involved in the EU PM. Indeed, interest groups are actors able to participate simultaneously to different levels of decision-making process.

5 According to the neofunctionalist/sovereignist perspective, national officials in the European context enjoy a certain degree of

autonomy, with respect to the positions of their governments, in the phase which involves them in negotiating decisions. Autonomy both towards the internal environment, that is towards the active national actors in Brussels, and towards the other competing national realities. The criticisms made of this approach have always focused on the fact that it was difficult to determine from whom these officials were legitimized in carrying out autonomous positions in the European negotiations. An issue from which the intergovernmental approach turns out to be more sheltered, whereas the position is widely negotiated internally in the national context, and therefore finds legitimacy in being a direct enactment of an executive, an expression of the popular will or in any case in line with the political balance national (Chelotti 2009: p. 39).

This aspect involves interest groups in a continuous effort of renegotiation of their aims. They are actors that use to change their positions moving form national to European levels. They have to maintain a certain degree of flexibility in terms of goals. they participate to the national decision making, so producing the national positions and then they change them, if necessary, during the EU PM. The methods of action of the interest groups are renewed and ensure that these actors remain crucial both in the elaboration and formation of the national interest, advancing their decision-making inputs within the national policy-making process, and at European level , thanks to this evolution of their role in the decision-making context of Brussels (eg Kohler - Koch 1997; Schmidt 1999; Cowles 2001; Beyers 2002; Quittkat 2006; Beyers and Kerremans 2007; Eising 2007

Fourthly, these actors are dynamical and involved in a broad set of relationships. They are relational actors, and for that they are crucial for my approach. We could include national coordination systems in the heterogeneous panorama of relations and strategies present within the world of European lobbying, as a particular variation of the relationship between decision-makers and groups. Socio-economic actors are a subgroup involved in relationships within the NCS. The role of domestic interest groups within this strategic coordination is outlined starting from a process of asserting one's own role and thanks to their ability to aspire to obtain new resources and to transform themselves into a sort of connection with society civil law aimed at legitimizing European decisions. The shared national action of the NCS would allow the individual interest group to enjoy the political resources of the member state in the European negotiation process, while at the same time national governments could enjoy a surplus of information and relationship resources made available by the network of groups of domestic interest necessary to make national lobbying more influential (Berry 1977; McCarthy/Zald 1977; Hojnacki/Kimball 1999; Guéguen 2007; Panke 2012). The NCS could represent a propellant for the quantity and quality of resources that a MS can use in its lobbying activity at European level. A further instrument, a heterogeneous mix of classical resources (informative, relational, economic and political) characterized precisely by a sharing of languages based on national commonality.