Academic Year 2017/18

First Level Master in

Electoral Policy and Administration

Mobilizing young voters

-a quantitative analysis of mobilization

activities.

Author

Acknowledgements

Thank you to my tutors at Sant' Anna University, Holly Ann Garnett and Melvis Ndiloseh for helping me clarify my methodology and my research question.

Also, thank you to the secretariat of the electoral board in the constituency of Assens for being so open and helpful with

everything. This is especially Janne Kornbeck, Lene Wilhøft and the entire communications department.

Thank you to the ones who have aided me in finding material for my dissertation. These are the teachers from the schools and institutions of the constituency of Assens and also The Institute of Political Science at The University of Copenhagen, Denmark and Center for Political Studies at The University of Southern

Denmark.

Also, the results of this dissertation are based on surveys and interviews made with the students in the schools in the

constituency of Assens. Thank you for participating, it was a great help.

Statement of authenticity

The work submitted in this dissertation is expressed in my own words, with my own ideas and judgments. All information is true, correct and accurate to the best of my knowledge. I understand that plagiarism is a crime and can be ground for expulsion.

Abstract

Voter turnout in Denmark is high compared to most other

countries. However, turnout among young people in Denmark was decreasing at local elections until 2013 where a mobilization strategy was implemented by the Danish constituencies in

collaboration with the Ministry of the Interior and Economy and the Organization of Municipalities in Denmark (Kommunernes

landsforening). This strategy resulted in a country- wide turnout of 67% among voters aged 18- 21 in the 2013 election and a 70.1% turnout in the constituency of Assens alone, which is the focus of this research. At the local elections on 21 November 2017 the constituency of Assens aimed to reach a 80% turnout among 18- 25- year- olds using a similar strategy as the one used in 2013.

In this dissertation theories about voter turnout are presented as well as the hypothesis that voting is a social act. The mobilization strategy used by the electoral board of the constituency of Assens is presented and through a descriptive quanititative method of questionnaires targeted at 696 young potential voters in 4 high schools with different socio- economic groups represented in the constituency of Assens, the impact of the components of the mobilization strategy is examined. The empirical evidence is analyzed without comparing ethnicity or gender.

The findings are that voting is indeed a social act so the activities involving networks such as friends and other youths have an impact. Many of these youths attend schools so educational institutions are important as a venue when spreading the

message. The families are important as a secondary group since the evidence collected for the dissertation shows that there is a spillover effect from the home to the potential voters.

Contents

List of Figures

1. Socio- economic groups………… page 33 2. Turnout over age groups…………. page 34 3. What strategies made you want to vote. page 37 4. Political talk in home and with friends.. page 39 5. Interest in politics………. page 40

1. Introduction

……… page 12. Theoretical Framework

……… page 5 2.1. The global decrease in young voterturnout vs. turnout in Denmark………… page 5 2.2. Voting as a social process……….. page 8 2.2.1. A spill- over effect………… page 10 2.2.2. Voting as a habit………….. page 12 2.3. Figures from the last local election

in 2013………. page 13

2.4. Assens constituency's mobilization

activities……… page 13

3. Methodology

………. page 23 3.1. Questionnaires as a method……… page 233.2. Ethics surrounding work with

human subjects……… page 25

3.3. The questionnaire……… page 27 3.3.1.: Analyzing the data………. page 29 3.3.2. Validity and reliability…….. page 30 3.4. The respondents……….. page 31

4. Analysis

………. page 345. Conclusion

……… page 416. Bibliography

………. page 447. Appendices

……… page 551: The questionnaire translated from

Danish………... page 55 2: Results of the questionnaire from

Vestfyns gymnasium……… page 59 3. Results of the questionnaire from VUC,

Fugleviglund and Det blå gymnasium……….. page 63 4. Invitation for schools to receive visit

or to visit the town hall.………. page 66 5 Competition: Create your own campaign

poster……….. page 67 6. Youth election………. page 68 7. Invitation to become a polling official… page 69 8. Post card competition……….. page 70

1. Introduction

The turnout at elections reflects the democratic health of the country (Elklit et al., 2009) since voting shows the citizens'

participation and support of the democratic system. To reflect the electorate best all groups must be represented and the turnout should be high so that the elected in office can work in all the electorate's interest (Lijphart, 2000). According to Elklit, this prevents a vicious circle of low turnout and low trust in the electoral system (Elklit et al., 2009).

Voter turnout is also crucial for the legitimization of governments and, thereby for keeping the stability of the state (Listhaug and Wiberg, 2000).

The young voters are important. Studies have shown that if young voters vote, they will keep voting through their lives so if we do not mobilize this group the risk is that whole generations of voters and, thereby participation in democracy will be weakened (Bhatti and Hansen, 2010).

Young voter turnout has experienced a worldwide decrease compared to the turnout of older voters (Bouza, 2014; Norris, 2004) and also in Denmark the young voters vote less than the groups of older voters. However, the voter turnout among young voters in the constituency of Assens, Denmark was high at the local election in 2013, making Assens particularly interesting to study. One reason for the high turnout is that mobilization activities

Danish local election in November 2017 The organization of municipalities in Denmark (Kommunernes Landsforening) asked their members to focus on increasing the number of voters aged 18- 25, the goal being at least an 80% turnout. To reach this goal, the media was central. The hypothesis for this research is that it is a social process to vote. The constituencies in Denmark have been good at focusing on this in their mobilization campaigns.

The research for this dissertation was carried out during an internship with the electoral board of Assens constituency. The research question was:

'What strategies are most effective in engaging youth in the constituency of Assens?'

Denmark holds local elections on the third Tuesday in November every fourth year. The statistics and analyses carried out by The University of Copenhagen and The University of Southern Denmark based on the voters lists from the 2013- election provide unique and valuable knowledge about voter mobilization strategies and are also the basis for the strategy used by Assens constituency in 2017.

By using the descriptive quantitative method of questionnaires to collect data from young voters in 4 different educational institutions of different socio- economic and educational backgrounds, data from a broad range of youth was found for this dissertation.

The group of voters from the ages of 18- 21 are in focus for the research as these are first- time voters. But they are also influenced by the mobilization strategies from 2013

(note: Assens mobilization activity targets voters aged

18- 25: the focus for this dissertation is the 18- 21- year-olds). When keeping to the schools and not organizations, overrapporting was avoided since many of the students in the schools also

participate in extracurricular activities in organizations.

The electoral board of Assens constituency does not itself have an official, written strategy for mobilizing young voters. However, by applying The ACE- Project’s steps for a media strategy for an electoral management board (from now on: EMB) it was possible to organize the components of their strategy in order to map the media and the roles of the stakeholders. This also showed when, how and to whom the messages were delivered.

The purpose for this research is to examine what parts of the mobilization activities in Assens constituency had the most impact on young voters.

The structure of this dissertation is quite classic. First, the

theoretical framework is described, giving an understanding of the paradox between the global decrease of voters since the 1980’s vs. the high turnout in Denmark. The hypothesis as the basis for the research question is also described: voting as a social process as opposed to the individual act of voting. The mobilization

strategy used by Assens constituency is introduced, using parts of the model developed by the ACE- Project, as well as figures from the last election in 2013.

the ethical principles to take into consideration when working with human subjects. The questionnaires and the subjects for the research are also introduced as well as the method for analyzing the data.

Finally, the analysis and the conclusions are made in chapters and 5.

A large part of the sources used for the theoretical research are Danish: Yosef Bhatti and Kasper Møller Hansen from The

University of Copenhagen, Jørgen Elklit from The University of Aarhus and Ulrik Kjær from The University of Southern Denmark. They have provided valuable knowledge about voter mobilization strategies and, in particular, the basis for the strategy used by Assens constituency in 2017. The appendices are also in Danish but the questionnaire has been translated into English.

The main sources for the methodological part are Schmedes og Nielsen, two Danish sociologists engaged in the method of quantitative research, and Bill Gillham, who is engaged in producing questionnaires, as well as the writer of literature for political science, Lotte Bøgh Andersen. To compare

questionnaires and the method of using interviews, Pranee Liamputtong has been used as a source.

2. Theoretical framework

This chapter presents the theoretical framework for this

dissertation. The hypothesis which is the basis for researching the subject of mobilizing young voters is also presented. Concepts important for the understanding of the subject are introduced, as well as the mobilization activities used by Assens constituency.

2.1. The Global decrease in turnout vs turnout in

Denmark.

Studies show that there has been a substantial decrease in the turnout for elections in Western democracies since the 1980's (IDEA (b), 2017). This concerns most countries with some

exceptions, such as the countries in Scandinavia. Denmark stands out, because the turnout for parliamentary elections has been fairly stable with app. 85% (Elklit et al, 2005). Elklit states some of the factors for this as:

Institutional facilitation

(practical arrangementsthat make voting easy):

Denmark has an automatic registration of voters as opposed to the voters having to register themselves, making it easier for the voter to participate. Postal voting is easy as well, and election day is mostly on a Sunday (except for local

Denmark has a large number of polling stations with a short distance between them.

Institutional mobilization

(practicalarrangements that motivate voters):

Concurrent elections increase turnout because there is more at stake. Denmark also has a proportional representative system which reduces the risk of wasting votes and this increases turnout as opposed to, eg first- past- the- post- systems. Denmark has a 2% threshold as well, with an open- list system, all of this increasing turnout.

On the other hand, Elklit writes that individual factors are also important for turnout. Elklit describes the following factors in Denmark:

Individual facilitation

(personal factors that makevoting easy):

Time, money, and civic skills influence turnout, as well as

education, as skills make it easier to acquire information. These are factors present in Denmark as the distance

between well- educated and less- educated citizens is small. Age influences turnout because people acquire political norms through life and older people belong to other

generations with other norms than the younger generations.

Individual mobilization

(personal attributes thatCitizens who are well integrated in society seek to live after the society's norms. Civic duty is a moral obligation to vote. Denmark is a very homogenous country and the feeling of moral obligation to vote is high. There is also a large degree of trust in the political system and democratic processes because of the transparency in the system, which make people vote. Denmark has a small population of app. 5 million and many voters feel that their votes count.

Elklit writes that voter turnout has not declined in Denmark because the new generations have been mobilized as well as other generations ( Elklit et al., 2005), across socio- economic groups. There is also a general support for voting as a civic duty because of the PR system described above and because the parties have been good at mobilizing voters due to the polerization in the political competition where right- wing parties and left- wing parties compete hard, setting the stakes high at elections.

In countries with strong party- alignments, voter turnout is high, as the group pressure from the parties create social norms ( Blais, 2000). This is the case for Denmark, where the political parties also, in general, have many mobilization activities at all types of elections, as described in part 2.2. There are also are large number of young candidates, a factor which could influence the young voters.

Elklit also theorizes that local elections receive less awareness than parliamentary elections since there is more power and

2.2. Voting as a social process.

The scientific basis for this research is the social choice theory which says that, even though the actual choice of candidate is highly individual, the outcome of the vote is a collective choice. Furthermore, even though the actual act of voting is individual, the processes leading up to the decision are social (Rose, 2000).

Most parts of a community take part in elections, with exceptions such as minors or non- residents. The hypothesis which this dissertation tries is that even though the actual act of voting is individual, the decision process is influenced by social effects. And so, voting is a social process (Hooghe, 2017). Lazarsfeld

describes it as:

"Voting, therefore, is a social act and the entire decision- making process leading up to the vote has traditionally been described as a process that is strongly influenced by the social network an actor is embedded in." (Lazarsfeld et al., 1944)

Hooghe writes that an election is often the only type of political activity that the electorate takes part in so mobilization strategies targeted towards voting will have to differ from mobilization

strategies targeted towards civil engagement in political activity. In this effort the social network is important since voters who

Hooghe divides mobilization strategies into three determinants for electoral turnout (Hooghe, 2017):

Mobilizing networks

: activities or organizations with theexplicit goal to mobilize voters. Eg. political organizations.

Informal networks:

not formalized and without the explicit goal to mobilize voters. This includes family and friends.Cultural or geographical contexts:

broader settingswithout political goal. This includes traditions and norms for civic participation in democracy.

These determinants influence the views expressed by the voters, either because of group pressure or because of the voter wanting to express positive behavior to be accepted by the group or perhaps, as in social science, because it is natural to exchange opinions with each other within a group. Whatever the reason, networks influence voter behaviour, see part 2.2.1. (Norris, 2004). Another study shows that spouses generally vote more than singles, again suggesting the social dimension of voting (Elklit et al., 2017).

Turnout increases when the surroundings vote and this should be taken into consideration in mobilization strategies: to promote voting as a social process and not only an individual choice (Bhatti and Hansen, 2010) and also to promote voting in social

surroundings such as schools and at youth elections. This supports an important finding in the research for this

dissertation: it is indeed a social act to vote but messages are also understood and received best in social settings. This means that mobilization strategies should include social events or venues such as educational institutions and social media.

2.2.1. A spill- over effect.

The turnout among young voters is often high among 18- year- olds but it decreases from the age of 19. For example, at the latest Danish local election the 18- year- olds voted 13.5 % more than the voters from the age of 19 ( Bhatti et al, 2014). This contradicts studies that show that voters gain the habit of voting later in life (Blais, 2000), see part 2.2.2. in this dissertation.

According to Danish studies from 2010, the parents' participation

in elections is the most important factor when young people decide whether to vote or not to vote (Bhatti and Møller Hansen, 2010). These studies are supported by International studies (Rose, 2000). According to Bhatti, a young Danish voter whose mother voted has a 30% higher probability of voting than a voter whose mother did not vote. If the father voted, the young voter has a 19% higher probability of voting (Bhatti and Møller Hansen, 2010). These numbers are calculated without taking into

consideration the parent's socio- economic conditions. Thus, the social heritage is strong as the parents are the primary role models for children.

Bhatti and Møller Hansen explains the difference in turnout among the first ages of eligibility to vote by 18- year- olds being influenced by the spill- over effect from the home. As soon as young people leave home they are more influenced by their friends (Bhatti and Møller Hansen, 2012). This could explain why the turnout is high among 18- year- olds but quickly starts to decrease from the age of 19. The studies also show that young voters are as influenced by their social contexts as by the parents once they leave home.

The fact that the network as well as the social heritage has an influence confirms that it is important to influence the secondary audience as well the voters themselves. Young voters vote if their surroundings vote and this fact can be used when mobilizing voters: to promote voting as a social act as opposed to an individual act (Bhatti and Møller Hansen, 2010). If the young voters are enrolled in schools, they have a 10% larger probability of voting, and this is a good reason for directing mobilization strategies towards social institutions such as schools, families and venues for leisure activities (Bhatti and Møller Hansen, 2010).

2.2.2. Voting as a habit

Studies have shown that voting may be a habit (Gerber et al., 2003) and that this habit influences the voter more than the factors of age and education. This means that it is important to get the young voters to participate in democracy early as they will

probably participate for the rest of their lives. The spill- over effect described in part 2.2.1. has an influence here.

If the young voters do not get into the habit of voting, the future generations of voter turnout will be low and this can influence the democratic health negatively, see part 2.1. Franklin writes:

"Turnout appears to be stable because, for most people, the habit of voting is established relatively early in their lives." (Franklin, 2004).

The habit of voting is created early in life and first- time voters mostly vote for high- profile elections. Additionally, mobilization strategies work best on young voters (Elklit et al., 2005) so these strategies are a good investment for the future democratic health of the country.

2.3. The figures from 2013.

Until 2013, there had been no studies of electoral mobilization strategies in Denmark as there were in e.g. the USA (Bhatti et al., 2014). Denmark had been used to a relatively high turnout at elections and there was no initiative to start mobilizing voters until 2009 where the turnout hit an all- time low of 65. 8%. The decline was especially evident among young voters, immigrants and unemployed voters (Bhatti, 2017). The result was that only certain parts of the population voted, thereby setting the agenda. This is why the mobilization strategy in 2013 was subject to research and why the material collected by the universities on the basis of the voter lists was so unique. The voter lists from the Danish local election in 2013 supply a substantial amount of important data.

The constituency of Assens is particularly interesting because of the large turnout among young voters and because Assens was the fifth best out of 98 constituencies to mobilize young voters. In 2009, 56. 55% of the 18- 21- year- olds in Assens constituency voted as opposed to 70. 95% in 2013 (Elklit et al., 2017).

2.4. Assens constituency's mobilization

strategy.

Assens constituency did not have an official written strategy for the mobilization of young voters for the 2017- election. Thus, the

strategy is for this dissertation described using a model inspired by the ACE- Project. The model is a useful tool for an EMB in

ensuring that all aspects of a strategy are covered in order to reach as large a part of the electorate as possible. The when, how and to whom are established and questions and concerns from the stakeholders are addressed. The strategy is developed as a tool for developing media strategies but in my opinion the model can easily be used to describe other strategies as well as it shows which parts should be altered and where to improve the strategy. In this case, the model covers the mobilization strategy used in Assens constituency.

The mobilization strategy is in seven steps (ACE- project, 2012). However, for this dissertation only the steps 2 and 4-7 are used. The reason is that step 1 concerns an analysis of the EMB staff and step 3 concerns the electoral cycle which is not relevant for the analysis of the mobilization activities. Anything to do with the electoral cycle is described in step 6.

Step 2: Stakeholders and mobilization networks

The EMB held regular meetings with stakeholders to help ensure their trust in the project, their agreement in decisions and ensure responsible media coverage. Any codes of conduct were also discussed here, as well as media legislation. The EMB and the stakeholders coordinated their deadlines, time plans anddiscussed the best techniques for publishing messages since the media is the link between the EMB and the public.

The mobilization strategy in Assens constituency involved Center for Journalism at The University of Southern Denmark, the media and the constituencies interested in the cooperation (in 2017: 76 of 96 constituencies). The media is mapped in step 5.

The organization Danish Regions (Danske regioner) and The Organisation for Municipalities in Denmark (Kommunernes landsforening) developed an online toolbox, similar to the one used for the campaign in 2013 (Toolbox, 2017) and an inspiration catalogue (Inspirationskatalog, 2017), at liberty for the

constituencies and media for producing a mobilization campaign. The toolbox and inspiration catalog contained materials such as films, statistics, facts and inspiration for competitions and

activities. The activities chosen by Assens constituency will be described in step 6 in this model.

There were 9 political parties and 96 political candidates in Assens constituency (formal networks). Among the parties were the youth departments which were involved in the mobilization strategy, as well as the following organizations that represented present or future voters:

19 schools, 33 kindergartens and 4 high schools as well as all their parents and families. Assens local council also had a youth board working for the improvement of educational institutions and culture for the local youth.

Funding: According to the head of secretary, Lene Wilhøft, the

elections and no funding comes from the state budget or external sources. The budget consists of 1.1 mill. Danish Kroner per election which is sufficient for the implementation of a local election in Denmark. The money can be transferred to the next election if it has not been used. Thus, the budget for the 2017 election was 1. 7 mill. kroner since extra funding was necessary due to new regulations regarding the access to vote for people with disabilities.

Step 4: Defining the audience

Knowing the audience enabled the EMB to design messages that could be easily understood by the groups that they wanted to reach.

The primary audience for the strategy was young people and children in the ages 6- 17 and 18- 25. Assens constituency has app. 6000 children aged 6- 17 and app. 3000 young people aged 18- 25 ( Danmarks statistik, Folketal 1A, 2017). The app. 200 voters from minority groups speak Danish and learn the language in school so they did not need information in their language. There are app. 1600 first time voters. These are the ones in focus for this dissertation.

97 % of the population in Southern Denmark have access to the internet (Danmarks Statistik, Seneste anvendelse, 2017). For this

dissertation it is supposed that the same number goes for the youth in Assens as the socio- economic level and the level of education is average compared to Danish figures. This includes the population on the small islands of Bågø, Torø and Helnæs as the IT- infrastructure is well established (Norris, 2001).

The secondary audience (the informal networks) that influenced the youths were friends, parents, the organizations and political parties mentioned in step 2, as well as the media that were engaged in the strategy. The secondary audience were reached through the same platforms as the primary audience.

Step 5: Mapping the media.

The EMB had created a database to ensure that the contact information to the stakeholders was relevant and updated.

The media in question consisted of the regional newspapers Fyens Stiftstidende and Fyens Amtsavis, which publish their papers both written and online and have app. 100,000 readers in all, regionally (Gallup, 2017).

Broadcasting media were the regional TV- stations TV2- Fyn as well as the national station TV2 with app. 50,000 viewers in all, regionally (TV2, 2017). The only radio involved was the regional radio DR-P4 with app. 155,000 listeners, regionally (Danmarks statistik, 2017).

order to quickly inform them in case the mobilization strategy was altered and in case any press releases were necessary. This could be changes of venues, information about the town hall's visits to schools or new videos about the election. The EMB held 2 joint meetings with the media in May 2017 and again in August 2017. The focus for the meetings was to create a common direction for the EMB and the media and also to ensure that the press complied with the expectations of the EMB and that they were party neutral. Any questions from the media were answered and the EMB knew where to direct the media if they had more questions (such as to the youth council, the schools and the candidates).

Additionally, the communications department participated in a theme day in April 2017 arranged by Kommunernes

Landsforening with a follow- up network meeting in May.

There is a free press in Denmark and legally, they have access to all information about public matters as administered by The

Danish Ministry of Justice (https://www.retsinformation.dk /forms/r 0710.aspx?id=152299). The press also has the legal obligation to report from all sides of the political spectrum, according to the law on media responsibility as administered by the media board (http://www.pressenaevnet.dk/medier/).

The use of social media in Assens constituency is wide and the EMB had daily outlets on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, making the internet a good platform for the EMB to deliver messages to the public. The constituency has its own Facebook page called "Assens kommune"

(https://www.facebook.com/assenskommune/?fref=ts) where the EMB posted any news relevant for the electorate, e.g. preliminary results and descriptions of the moods at voter meetings or at the polling stations on election day. The stakeholders were also invited to interact with the EMB on the Facebook page, with the EMB chatting under controlled circumstances to keep the level serious, this way checking for any false rumors and making the EMB able to react quickly to stop this. The EMB used a chat robot called "Solvej" on the Facebook page, for the purpose of chatting or tipping the press about election related stories

(https://www.facebook.com/assenskommune/?fref=ts).

Step 6: Tools and techniques

The mobilization strategy used by Assens constituency for the 2017 election was the same as the one in 2013 but with an extra focus on social media. Thus, the messages had been tested to reach the 18- 25- year-olds who were in focus. The tools and techniques were taken from Kommunernes Landsforening' s toolbox (http://www.stem.dk/toolbox/kommunal/) and the Inspiration Catalogue (https://www.kl.dk/ImageVaultFiles/id_

82032/cf_202/Inspirationskatalog_-_Kommunalvalg_2017.PDF). The campaign was called: "Tænk dig om før du IKKE stemmer" (translated: "Think before you do NOT vote" ).

The EMB chose five activities from the toolbox, most of them activating the voters themselves:

1. Visits to schools (appendix 4).

The secretariat visited 4 high schools and 8 schools with the

grades 0- 10 during October and November and also received 3 visits from the schools to the town hall and the mayor's office. There was a quiz and they could win a bag of sweets. The young people also participated in a council meeting. The purpose was civic education: to inform and educate young people in Assens constituency about the local political system, elections, the areas that the local council have influence on and to make the

youngsters aware of ways to get influence in Denmark.

2. A competition for students: "Create your own electoral

campaign" (appendix 5).

The young people in the oldest classes and high schools were

invited to create a suggestion for a campaign targeted young voters, to get them to vote. The winner was the class 2.B at Vestfyns Gymnasium- one of the high schools which is in the focus for this research. The winner won a trip to Copenhagen for the class, to visit the parliament. The judges were the local youth council.

The purpose was to make the youngsters remember to vote and the winning video can be seen on Youtube

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjPSGr5WifM).

3. Youth election (appendix 6).

A mock election on the same day as the local election involving

students from 8th, 9th and 10th grade in 18 schools. They voted for the same candidates as in the real election and the results were publicized by the EMB at 20.00 o'clock, at the closing of the

polling stations. Students from 3 high schools were polling officials for the youth election and the classes 0- 7 were invited to visit. Polling station look-a-likes were placed in the schools with ballots and ballot boxes. The purpose was to create a feeling of elections at all schools and to capture the students' interest in democracy by giving them a sense of influence.

4. Polling officials (appendix 7).

An opportunity for the youngest voters 18+ to participate as extra

counters on the evening of the election. The purpose was to give the young people an understanding of how elections are

conducted and how the ballots are counted.

5. Parent campaign: Bring your children (appendix 8). 5000 post cards called "Kom, vi skal huske at stemme"

(translated: Come on, let's remember to vote) were sent to 19 schools and 34 kindergartens all over the constituency. The children could win a cake and an iPod for their class. The children painted on the post cards and could only hand them in at the polling stations, as to make sure that they went there. The purpose was to make children aware of the election and to tell their parents to vote and, then go to the polling station. The winning postcard can be seen on the front page of this dissertation.

Other mobilization methods such as posters and radio- spots were also used but the effects of these are difficult to analyze as it can be hard to say exactly what specific groups of voters were targeted.

Step 7: Message development.

The messages that Assens constituency wanted to give were:

- If the mother votes, the children will vote. This is the spill-

over effect described in part 2.2.1. in this dissertation.

- Voting should become a good habit. This is a reason why first-

time voters are important. Studies show that voters continue to vote if they have started early, see part 2.2.2.

- The EMB wanted the percentage of voters aged 18- 25 to reach 80% in 2017. The figures from the latest elections are

presented in part 2.3 of this dissertation.

- A high voter turnout is a sign of a healthy democracy and

influence is only reached by participating in it, e.g. by voting. If you do not vote then you cannot complain about the system and the politicians and the other voters will decide how the country is managed. Democracy concerns us all. As it is now, the largest percentage of the active voters are represented by the richest, oldest, best educated and the employed. These groups will have all the influence if the voter turnout is low.

- Election day is a celebration of our democracy. Not all

countries in the world have well- functioning democracies and we should cherish it or else we could lose it.

3. Methodology

This chapter explains the methodology of using questionnaires for collecting empirical data, the ethics surrounding the method, the design of the questionnaire, a description of the subjects involved in the research and how the empirical data is analyzed.

3.1. Questionnaires as a method.

To test the hypothesis described in part 2.2 in this dissertation

about voting being motivated socially, a questionnaire was developed (appendix 1). This quantitative method is known from the area of social science, to collect quantitative data (Nielsen and Schmedes, 2009). Ackroyd and Hughes define questionnaires as:

“…concerned to gain information from respondents in order to test some theoretical explanation and represents the full- blown expression of variable analysis in the survey tradition” (Ackroyd and Hughes, 1992).

In using questionnaires the researcher must be objective and precise to produce reliable and valid data (Bøgh Andersen

et al., 2012), in order to be able to induce meaning. In the words of Bill Gillham:

"The essential point is that good research cannot be built on poorly collected data;" (Gillham, 2007).

The hypothesis behind using questionnaires for this research is that it is possible to measure and uncover people's position and opinions quantitatively. The method of using a questionnaire is suited for this research because it is a good way to collect precise information about how the students have experienced the

activities engaged by the EMB. Another advantage is that a large number of answers can be collected and the number of returns are high. The data is also easy to sort and analyze compared to e.g. interviews. The questionnaires can be generalized into describing a whole population which is what is needed in this dissertation to describe how many of the voters are influenced by social activities and norms.

A disadvantage when using questionnaires as a method is that there can be gaps in the answers, making it difficult to reach a full picture since the questions cannot be rephrased or repeated as in interviews. Also, the researcher cannot see the subject's

nonverbal reactions and the student cannot go deeper into the question or describe the answer with her own words, and this could create some shortage in the quality of the answers. This makes it difficult to decide the causality of the answers.

Questionnaires do not describe feelings or behavior very well. They are best to describe objective observations.

It must be noted that the respondents were on forehand subject to short, informal interviews to see what would be relevant to ask

about in a questionnaire (Liamputtong, 2011). The interviews were also a kind of sampling to test if the students at the high school were suited for the research.

The students were selected randomly from the school's list of enlisted students. We cannot know if the students from the sample actually answered the questionnaire but it can still provide some reliability to the method.

The questionnaires were self- administered using the internet which gave the respondents some flexibility in time and place to answer. A disadvantage in using this method is that it is unknown if the respondent has answered it in cooperation with e.g. friends or family, making it unclear if the responses reflect some kind of social desirability (Bøgh Andersen et al., 2012.). Somebody else could, in theory also have answered the questions for the

respondents. This would give a false picture. Another

disadvantage is that the number of responses could have been low. To prevent this a reminder was sent to the students 3 days before the deadline, to increase the possibility of a high number of responses (Bøgh Andersen et al., 2012).

3.2. The ethics surrounding work with human

subjects.

The questions as well as the range of answers used for

questionnaires are determined by the researcher (Gillham, 2007). Thus, there are ethical principles to be taken into consideration

when working with human subjects. The researcher has a responsibility towards the respondents in keeping their names anonymous. Their responses must also be treated in a scientific way, ensuring that the research is serious and that the results of the analysis provides knowledge about human lives (Ackroyd and Hughes, 1992).

When working with human subjects it is necessary to get their acceptance of the fact that the answers will be used for scientific research. For this purpose the teachers at the high schools were asked to write this in the invitation which they sent out with the questionnaires. This way the students were informed before they answered the questionnaire, and they could also decide not to answer. The questionnaires were also presented personally to the teachers on forehand so that they could assess them before they were distributed to the students. The teachers have not meddled with the questionnaires, only recommended some changes. A pilot of the questionnaire was presented to six of the students before distributing it to the rest of the schools, to check if the questions were too long or unclear, to prevent any

misunderstandings, as recommended by Oppenheim (Oppenheim, 1992).

Another ethical principle is that the researcher should inform about the results of the research (Nielsen and Schmedes, 2017). Thus, copies of this dissertation will be sent to the teachers and students at the relevant high schools and to the EMB in Assens constituency.

3.3. The questionnaires.

The hypothesis which the questionnaire is based on is described in part 2.2. in this dissertation: the actual act of voting is individual but the process leading up to voting is social.

To try the hypothesis there are three types of questions about the research area (mobilization of voters) in the questionnaire:

1. Questions describing the voting habits of family and friends.

2. Questions describing the mobilization strategy of 2013 and the influence on the student.

3. Questions describing the mobilization strategy of 2017 and the influence on the student.

The focus for the research is on the 18- 21- year- olds only. This age group voted for the local elections for the first time in 2017 and, thus are first time voters for a local election. The age group was under 18 at the latest local election in 2013 and were subject to the same mobilization strategy. This means that it should be possible to see some consequence of the mobilization strategy of 2013. It should be noted that there has been a parliamentary election since 2013.

The way that the questions are phrased verifies or falsifies the hypothesis, the ultimate analysis showing if the hypothesis is right.

The answers can be measured to test the hypothesis, as

described by Bøgh Andersen et al. (Bøgh Andersen et al., 2012) NOTE: There are two answer sheets (appendix 2 and 3) as the schools had different intranets. Two of the questions were

arranged differently but the actual phrasing is the same. Question 17: “How interested are you generally in politics” was, by mistake, never sent to the respondents in appendix 3 but for this research I will treat the responses equally as the socio-economic groups were similar in the schools.

The questions in the questionnaire are phrased precisely and the options are short and clear to make it easy for the respondent (Nielsen and Schmedes, 2009) since the questions cannot, as in interviews quickly be rephrased to clarify, see part 3.1.

Additionally, the answer to open ended questions can be difficult to interpret. Thus, the respondent's thoughts behind the answers are not collected but the questionnaire is designed to best answer the questions inside the given framework, to represent the

population best.

There are no too personal questions apart from the ones about age and education. This is to avoid discouraging the students from answering the questionnaires (Bøgh Andersen et al.,2012).

The language in the questionnaires is easy and there are only 16 questions, easy to answer. This should increase the percentage of answers as the questionnaire takes no more than 15 minutes to answer, as not to tire the respondent too soon.

possible as the answers should be influenced as little as possible by the researcher, as recommended by Bøgh Andersen et al. (Bøgh Andersen et al., 2012). Technical terms have also been avoided to avoid that the student does not understand the question.

There are several options to answer most of the questions except the ones about age and education. More options increases the probability of the returns being honest since the students will not be forced to answer wrong because of a lack of options. This is an advantage since all answers are needed to produce valid data. For this reason there are no options called "not known".

The questions are sorted logically to make it easy for the respondent to see the structure. I have taken into consideration that one question can easily influence the respondent's answer for the next question.

3.3.1. Analyzing the data.

The questionnaires are analyzed using 4 variables. It has been taken into consideration that the number of responses does not represent the whole population and we will not know whether the mobilization strategy has had an impact until the figures have been analyzed next year but the questionnaire gives a picture of the trends. The ultimate question is if the number of responses are enough to show a general picture of the population (Nielsen and Schmedes, 2009) and if one approach is adequate for the

researcher to have confidence in the findings (Gillham, 2007).

The analysis is confirmative: the questions are grouped to test the hypothesis as opposed to an explorative analysis where the

questions are grouped on the basis of the collected data (Oppenheim, 1992). The variables used for the analysis are:

Age: (see part 2.2).

Socio-economic groups: do these variables have an

influence on the voters’ response to the mobilization activities?

Participation in the 5 activities for mobilizing voters

(listed in part 2.4.)

The level of interest in politics.

3.3.2. Validity and reliability.

The questionnaires contain two personal questions serving as control questions (Nielsen and Schmedes, 2009):

1. Age

2. Parents' level of education.

the data into categories and also to see who the respondents are. They also help the reliability of the method as the same questions can be used for similar research (Nielsen and Schmedes, 2009). The question about the students' age is important to see if there are significant differences in the turnout among the different age groups. The difference could be due to personal circumstances such as the novelty of voting but it could also be a sign that the voter is still influenced socially by the family.

The second question is to see if there is any differences in the turnout in different socio- economic groups even though the high schools serve students from all socio- economic groups in the constituency. This ensures that a general picture of the young voters can be made in the conclusions of this research.

The control questions help the validity of the questionnaire and the validity is also tested using the interviews and pilots described in part 3.1.

3.4. The respondents.

The questionnaire was distributed via intranet to 18- 21- year- olds in 4 different high schools in Assens constituency, targeting 696 students from the whole constituency. The schools' intranet was an easy way to distribute the questionnaires to only the 18- 21- year- olds as their ages are registered there. Another reason for using this database is that it is illegal in Denmark to use the civil register for research as the social security numbers registered

here are personal and secret.

Thus, the questionnaires have not reached young voters not enlisted in an educational institution.

Although studies has shown that gender has some relevance for the voter turnout the students chosen for this research have not been divided in to genders. The students are so young that the gender should not have much significance at this age.

The four schools are:

Fugleviglund Produktionsskole, a continuing education with

special options for young people with social or academic challenges. 31 of the students were aged 18-21.

VUC Glamsbjerg: a public high school for young adults. 205 of

the students were aged 18-21.

Vestfyns gymnasium: a public high school for students entering

directly from 9th or 10th grade. 339 of the students were aged 18- 21.

Det blå gymnasium: a public high school for students entering

directly from 9th or 10th grade, with a focus on business studies. 121 of the students were aged 18-21.

The reliabilty of the data is high as the number of returns were 475. This means that app. 29. 6% of the 18- 21- year- olds in

Assens constituency answered the questionnaires when the number of 18- 21- year- olds has been set to 1600 and 68. 2% of the target group in the 4 schools answered. These results

correspond with Ackroyd and Hughes' recommendations for the number of returns to be at least 1/4 for the data to be valid (Ackroyd and Hughes, 1992). The reliability of the data is also good as there is a good chance that similar research with the same number of respondents would give the same result, as described by Nielsen and Schmedes (Nielsen and Schmedes, 2009).

The questionnaires were collected during a two- week period and the deadline was on the November 22, the day after the election. This ensured that the respondents did not forget about the task and that they had enough time to answer the questionnaires, according to their own schedules. The high schools serve students from all socio- economic groups in the constituency and this

should help get a general picture of the young voters.

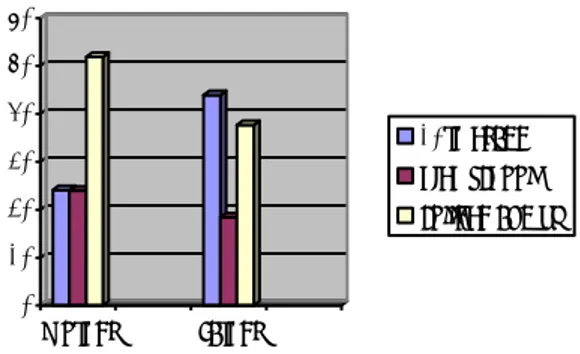

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 mother father 10th grade high school college and up

54. 11% of the respondents were 18 years old, 45.49% were aged 19- 21 and 0.4% have not answered the question about their age. Figure 1 shows the representation of socio- economic groups based on the parents’ level of education.

4. Analysis

Variable 1: age.

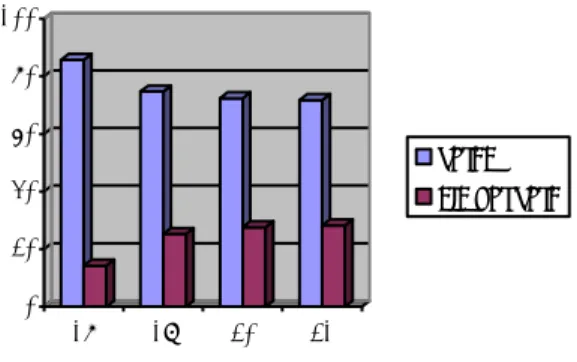

Figure 2 shows that 90. 7% of the 18- year- olds voted but that the turnout decreases rapidly over the age groups. This could be because there was a parliamentary election in 2015 so that the first-time voters have actually voted before so the novelty of voting was gone. 0 20 40 60 80 100 18 19 20 21 voted did not vote

Figure 2: turnout over age groups

The novelty of voting can have an influence on the first-time voters as well as the large influence from their informal networks,

see part 2.2.1. The diagram confirms studies that show that if voters live at home, they are 10% more likely to vote ( Bhatti and Møller Hansen, 2010). It also confirms that the social heritage described in part 2.2.1. is strong so it is important for a

mobilization strategy to reach the secondary as well as the

primary audience. Of course, this is provided that the target group for this research actually live at home.

The 19- 21- year- olds have not had children yet, or old parents to take care of so many of the political topics for a local election might not be as relevant for them as for older generations. The older voters are also more influenced by their non- voting friends since a large part do not live at home, see part 2.2.

A point to be made here is that the turnout is high in this diagram but since the individual mobilization (see part 2.2.) in the form of a strong norm about voting in Denmark, the question: ”Did you vote” is not precise enough as a Dane would probably answer yes to this question, anyhow.

Variable 2:

socio- economic groups.The representation of socio- economic groups has been shown in figure 1. The diagram does not show if the socio- economic level has any influence on turnout. On the contrary, comparing with the general high level of turnout in all age groups in figure 2, it shows that the turnout has been even across socio- economic groups. This can be explained by the good individual facilitation of voters

in Denmark, see part 2.1.

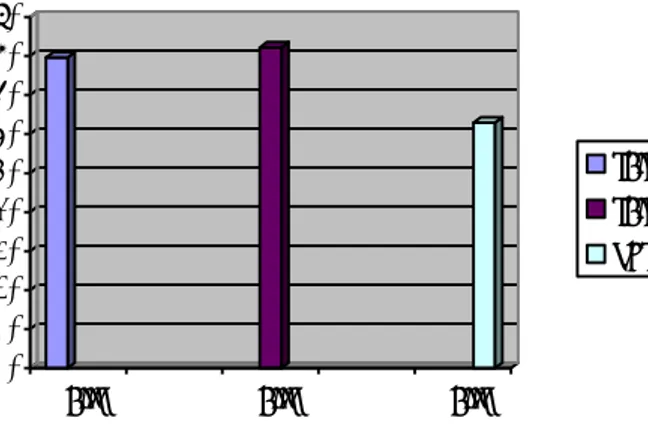

Variable 3:

Youth participation.The youth participation in mobilization activities are shown in figure 3. The diagram shows whether the voters were mobilized by participating in the 5 activities. However, it does not show if they were mobilized by participating themselves or by the participation of others, thereby being influenced by a secondary group. This should have been specified when asking the question.

The postcard competition is highly represented which suggests that the spill- over effect from home, mentioned in part 2.2.1. had an impact. The youth election is also well represented which confirms the hypothesis about voting being a social process and that mobilization activities should be carried out in social

sorroundings. The relatively low participation in the “Create your own campaign”- competition and the job as a polling official, activities involving less social interaction also proves this point.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

participation in

postcards

wanted to vote

because of

postcards

participation in

competition

wanted to vote

because of

competitions

youth election

wanted to vote

because of youth

election

Visits to/from

town hall

wanted to vote

because of visits

to/ from town

hall

polling official

wanted to vote

because of job as

Figure 3: What strategies made you want to vote (page 37)?

An important thing to have in mind is that, even though the respondents did not actively remember the activities, they could have been influenced by them anyway, years later.

One interesting point to make when comparing age, political activity and social mobilization strategies is that the Danish youth is not as individualistic as is sometimes claimed by older

generations.

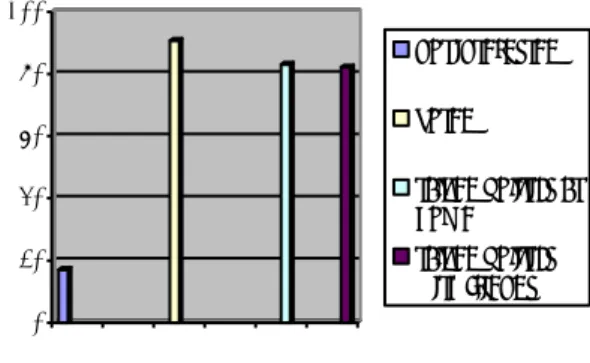

Variable 4:

interest in politics.Figure 4 shows that 79. 6% of the target groups talked about politics in their childhood home and that 62. 9% went to their polling station with their parents. When comparing these numbers to figure 3 it is clear that the social activities have the largest impact.

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

all all all

talk with parents talk with friends voting with parents

Figure 4. Political talk in home and with friends.

Appendix 2 and 3 show that 96.12 % of the respondents have daily access to social media. This corresponds well with the media map described in part 2.4., that 97% of the population of Assens constituency has access to the social media. However, it also shows that less than 35% of the target group reads newspapers regularly while 27. 1% never read them. This means that the newspapers are not suited to reach the target group and that the social media is better. This could be of significance for the reach of Assens constituency’s mobilization strategies as they have used social media to inform about the activities. Additionally, if the process of voting is social then social media would be obvious to use for a mobilization strategy.

However, the social media also includes the newspaper

homepages and according to the communications department in Assens constituency they should have agreed more about what

the expectations were, as there were some bad coverage about the young voters, and this might have influenced the readers to not vote, see part 2.4.

0 20 40 60 80 100 not interested voted talked politics at home talked politics with friends

Figure 5: Interest in politics.

Another interesting observation is that in the first questionnaire (appendix 2) the respondents not interested in politics was 17.05% but the number of voters in figure 2 was 90.7%. However, 83.08% talked about politics at home and 82.17% talked about politics with their friends. This indicates that there could be individual

5. Conclusion

The research question was:'What strategies are most effective in engaging youth in the constituency of Assens?'

475 responses were received to a questionnaire distributed to 696 students aged 18- 21 in 4 high schools in Assens

constituency. The responses were analyzed using the 4 variables: age, socio- economic level, participation in the 5 activities for mobilizing voters and the degree of interest in politics.

The hypothesis was that voting is a social process. The mobilization strategies which took place in social venues and contexts such as schools and social activities should have the largest impact om the young voter turnout.

Findings.

The findings confirm the hypothesis about voting as a social process, as well as voting as a habit to be formed early and the spill- over effect from home. However, influence can be difficult to measure as influence can also be secondary.

social activities that had the most impact as well as the informal networks such as family and friends. In the analysis the post card competition for children had the largest impact, even 4 years after the first postcard competition. The activity with the second highest impact were visits to or from the town hall.

However, it is difficult to say what exact activity has the best impact as the activities could have had other effects than

increased turnout: the activities could have had an effect on the awareness of elections and they could have visualized the practical arrangements of elections for the children. The

knowledge about politics and society can have been increased and this, in turn can have a positive consequence for the future turnout and engagement of young voters. Not all of the young voters participated in all of the activities so it is difficult to say how much they have been influenced by them.

The findings are made in a Danish context with a high turnout, a good IT- infrastructure and a high social norm for voting so they cannot necessarily be used in an international context. However, the data is reliable because of the large number of responses and it is valid because it measures the desired variables.

Some surprising findings are that the young people aged 18- 21 do not think as individually as is sometimes claimed. They are actually very social.

Questionnaires.

Questionnaires give the opportunity to collect precise, measurable data and it can easily be sorted. However,

questionnaires do not measure feelings very well and it is difficult to clarify questions which would be possible in an interview. Also, the social norm is strong in Denmark so some of the questions should have been more precise since there is a chance that the responses were not always entirely truthful. A way of helping to generate questions for the questionnaire would be to engage in structured interviews with the respondents before producing it so that the themes would be known and the questions would be more precise (Liamputtong, 2011).

In other words, it is beneficial to combine questionnaires with other methods when using this method for research as this gives a broader picture and as atomization ignores the other factors of voting. It is more time- consuming but also more in- depth.

Recommendations.

Some of the activities could have been changed a little by the EMB: for example the students could have been collected by buses and taken to the town hall instead of the town hall visiting the schools. This way the surroundings would have been more election- related and perhaps the students would have asked other types of questions through influencing each other, and the visit to the town hall would consequently have more impact.

In a future study it would be interesting to compare the voter’s lists with the civic register (and in some way ignore the Social security numbers) to get the actual non- subjective results in order to compare them to the subjective understandings of the

mobilization strategy. That way the results for ethnicity, age and socio- economic turnout could be researched more in-. depth. Time is also a variable to use to measure the difference between the prospective turnout in the beginning of the mobilization

campaign and after the election.

Assens constituency had a goal to increase the turnout among 18- 25- year- olds to at least 80%. The results will be published in the spring of 2018 and it will be interesting to see if they reached the goal.

Bibliography

Books

Ackroyd, S. and Hughes, J: Data collection in context. Longman, 1992.

Blais, A.: To vote or not to Vote. The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000.

Bøgh Andersen, L., Møller Hansen, K., Klemmensen, R., Lund Jensen,K.: Metoder i statskundskab. 2nd edition. Hans Reitzel, 2012.

Downs, A.: An economic theory of democracy. Harper and Row, 1957.

Elklit, J., Elmelund- Præstekær, C. and Kjær, U. (ed.): KV13. Analyser af kommunevalget 2013. Institute for History and Social Science at Syddansk University Press, 2017.

Franklin, M. N.: Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral competition in Established Democracies since 1945. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

G

Grreeeenn,,DDoonnaallddPP..aannddGGeerrbbeerr,,AAllaannSS..::GGeettOOuutttthheeVVoottee!!HHoowwttoo

I

InnccrreeaasseeVVootteerrTTuurrnnoouutt..22nnddeeddiittiioonn..BBrrooookkiinnggssPPrreessss,,22000044..

Lazarsfeld, Paul Felix: The People's Choice: How the Voter makes up his Mind in a Presidential Campaign. Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1944.

L

Leevviinnssoonn,,PPaauull::NNeewwNNeewwMMeeddiiaa.. PPeenngguuiinnAAccaaddeemmiiccss,,22000099..

Liamputtong, P.: Focus Group Methodology. Sage Publications, 2011.

Møller Hansen, K., Kosiara- Pedersen, K.:

Folketingsvalgkampagnen 2011 i perspektiv. Jurist- og Økonomforbundets forlag, 2014.

Norris, P., Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Norris, P.: Electoral Engineering. Cambridge University Press, 2004. Pp. 151- 176.

Norris, P., Curtice, J., Sanders, D., Scammell, M. and Semetko, H. A.: On Message: Communicating the Campaign. Sage

Publications, 1999.

Oppenheim, A. N.: Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement. Continuum, 1992.

Articles

Aldrich, J.W.: Rational Choice and Turnout. American Journal of Political Science, vol.37, no. 1, 1993, pp. 246-278.

Bhatti, Y.: Distance and Voting: Evidence from Danish

Municipalities. Scandinavian Political Studies, vol. 35, no. 2, 2012, pp. 141- 157.

Bhatti, Y., Dalgaard, J. O., Hedegaard Hansen, J., Møller Hansen, K. (a): Evaluating the Effect of Government communication

Towards Young Citizens- A Randomized Wait- list Field

Experiment. University of Copenhagen, 2014, Assessed on 14 November, available at:

http://cvap.polsci.ku.dk/publikationer/arbejdspapirer/2015/Bhatti_et

_al._2014_-_Evaluating_the_effect_of_government_communication_towards_ young_citizens._A_randomized_wait-list_field_exp

Bhatti, Y., Dalgaard, J. O., Hedegaard Hansen, J., Møller Hansen, K. (b): Hvem stemte og hvem blev hjemme? The Instutute for Political Science, University of Copenhagen, 2014. Assessed on 9 November, available at:

http://cvap.polsci.ku.dk/publikationer/arbejdspapirer/Hvem_stemte _og_hvem_blev_hjemme__final_.pdf

Bhatti, Y., Dalgaard. P. O., Hedegaard Hansen, J., Møller Hansen, K.: Kan man øge valgdeltagelsen? University of Copenhagen, 2013. Assessed on 14 November, available at:

http://www.kaspermhansen.eu/Work/MobiliseringKV2013.pdf

Bhatti, Y., Dalgaard, J. O., Hedegaard Hansen, J., Møller Hansen, K. (a): Mobiliseringsinitiativer ved KV13. University of

Copenhagen, 2015. Assessed on 14 November, available at:

http://cvap.polsci.ku.dk/publikationer/arbejdspapirer/2015/KV13_M obiliseringstiltag.pdf

Bhatti, Y., Dalgaard, J. O., Hedegaard Hansen, J., Møller Hansen, K. (c): The Calculus of get- out- the- vote in a high turnout Setting. University of Copenhagen, 2014. Assessed on 14 November, available at:

http://cvap.polsci.ku.dk/publikationer/arbejdspapirer/2015/The_cal culus_of_get-out-the-vote_in_a_high_turnout_setting.pdf

Bhatti, Y., Dalgaard. P. O., Hedegaard Hansen, J., Møller Hansen, K. (b): Valg: Sådan får vi flere til at stemme. www.videnskab.dk, 2015. Assessed on 9 November 2017, available at:

https://videnskab.dk/politologisk-arbog-2015/valg-sadan-far-vi-flere-til-stemme

Bhatti, Y, and Møller Hansen, K. a: Leaving the Nest and the Social Act of Voting: Turnout among First- time Voters. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, vol. 22 no.4, 2012, pp. 380- 406.

Bhatti, Y. and Møller Hansen, K. b: Valgdeltagelsen blandt danske unge. A working paper for The Institute for Political Science at The university of Copenhagen, 2011. Assessed on 9 November 2017, available at:

http://forskning.ku.dk/find-en- forsker/?pure=da/publications/valgdeltagelsen-blandt-danske-unge(f0824152-6d71-4863-a329-e9b955a6f968).html

Bouza, L.: Addressing Youth Absenteeism in European Elections. Assessed on 19 November 2017, available at:

http://www.youthforum.org/assets/2014/02/YFJ-LYV_StudyOnYouthAbsenteeism_WEB.pdf

Brambor, T., Clark, W.R., Golder, M.: Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, no.14, 2005, pp. 63- 82.

Coronel, Sheila S.: The Role of Media in Deepening Democracy. Assessed on 9 November 2017, available at:

http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan0 10194.pdf

Darmofal, D.: Reexamining the Calculus of Voting: A Social Cognitive Perspective on the Turnout Decision. Political Psychology, vol. 31, no. 2, 2010.

Davenport, T.C., Gerber, A.S., Green, D.P., Larimer, C.W., Mann, C.B., Panagopoulos, C.: The Enduring Effects of Social Pressure: Tracking Campaign Experiments over a Series of Elections.

Political Behaviour, 2010, 32: pp. 423- 430

Dhillon, A., Peralta, S.: Economic Theories of Voter Turnout. The Economic Journal, vol. 112, no. 480, 2002.

Elklit, J. and Togeby, L.: Where turnout holds firm: The Scandinavian Exceptions: In DeBarbelen, J., Pammett, J.H.: Activating the Citizen. Macmillan Press, 2009, pp. 83- 105.

Elklit, J., Toreby, l. and Svensson, P.: Why is Voter Turnout Not Declining in Denmark? Department of Political Science, University of Aarhus, 2005. Available at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255586846_Why_is_Vot er_Turnout_Not_Declining_in_Denmark

Fuchs, D., Guidorossi, G., Svensson, P.: Support for the

Democratic System. In: KKlliinnggeemmaannnn,,HH..,,FFuucchhss,,DD((eedd..))::CCiittiizzeennss a

annddtthheeSSttaattee,,pppp..332233--335533..OOxxffoorrddUUnniivveerrssiittyyPPrreessss,,11999955..

Gerber, A.S., Green, D.P. and Larimer, C.W.: Social pressure and voter turnout. American Political Science Review , vol.102, no. 1, 2008, pp. 33- 48.

Gerber, A.S., Green, D.P., Shachar, R.: Voting may be Habit- forming: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. American Journal of Political Science, vol. 47, no. 3, 2003, pp. 540- 550.

Gurin, P., Gurin G., Morrison, B.M., Personal and Ideological aspects of internal and external control. Social Psychology, vol.

41, no. 4, 1978, pp. 132- 159.

Hooghe, Marc: Social Networks and Voter Mobilization. In: The SAGE Handbook of Electoral Behaviour, pp. 241- 262. SAGE Publications, 2017.

Lijphart, A: Turnout. In: International Encyclopedia of Elections, pp. 314- 321. Macmillan Press, 2000.

Listhaug, O. and Wiberg, M.: Confidence in Political and Private Institutions. In: KKlliinnggeemmaannnn,,HH..,,FFuucchhss,,DD((eedd..))::CCiittiizzeennssaannddtthhee

S

Sttaattee,,pppp..229988--332222..OOxxffoorrddUUnniivveerrssiittyyPPrreessss,,11999955..

Made Hagelskjær, C.: Usikre unge får hjælp fra netværket. Assessed on 14 November 2017, available on:

http://maerkesag.dk/blog/usikre-unge-faar-hjaelp-fra-netvaerket/

McClurg, S.D.: Social Networks andPolitical Participation: The role of social interaction in explaining political participation. Political Research Quarterly, vol.56, no. 4, 2003, pp. 448- 465.

Nickerson, D.W.: Does email boost turnout. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, vol. 2, no. 4, 2008, pp. 369- 379.

Nielsen, Geert a. and Schmedes, K.: Spørgeskemaundersøgelser i et metodeperspektiv. Assessed on 10 November 2017, available at:

http://www.forlagetcolumbus.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/Lede_s poerge.pdf