1 Introduction

Psychotic depression is a “syndrome characterized by pronounced neuro-vegetative

signs and symptoms, with or without a thought disorder” (Schatzberg, Rothschild,

1992).

In DSM-III (1980) and DSM-III-R (1987) the dimensional qualifier 'with psychotic

features' was used to characterize a subtype of major depressive episode.

The approach to the problematic area of ‘psychotic (or delusional) depression’ is still twofold: a) it might represent a distinct subtype of depression, with peculiar clinical features, prognosis and treatment response (Charney DS, Nelson JC, 1981; Gershon ES, Hamovit J, Guroff JJ et al, :1982; Glassman AH, Roose SP, 1981); b) psychotic features might represent a marker of severity of major depressive episodes.

In several studies with different rating scales for depression, patients with psychotic major depressive episodes (MDEs) showed higher scores than patients without psychotic symptoms, especially when psychomotor retardation and cognitive disturbances were explored. Moreover, a number of other symptoms were over-represented in patients with psychotic depression, namely „depressed mood‟, „paranoia‟, „hypochondriasis‟, „anxiety‟, and increased feelings of guilt. (Rothschild et al 1989; Charney DS, Nelson JC, 1981; Lykouras et al., 1984; Lykouras et al, 1984, Glassman, Roose, 1981; Parker et al., 1991).

The course of the depressive disorder is different in patients with psychotic features. Psychotic MDEs are characterized by longer duration of illness (Coryell et al, 1987; Maj et al, 2007 ), greater likelihood of recurrence (Lykouras et al, 1984, Aroson et al,

2

1988), longer duration of episode (Maj et al., 2007), higher risk of suicide (Black et al, 1988; Vythilingam et al, 2003), higher number of hospitalizations (either medical, or psychiatric) and higher rates of comorbidity (specifically with OCD, somatization disorder, simple phobia) (Johnson, Horwarth, Weissmann, 1991).

Nonetheless, a 10-year follow-up study on 452 patients with an index episode of major depression showed that the presence of delusions was not associated with a worse psychosocial outcome on the long-term (Maj et al., 2007).

This finding may indicate that the prognostic significance of delusions in major depression tends to become weaker over the long term, as previously observed by Coryell and Tsuang (1982).

With regard to treatment, half of the depressed patients, refractory to antidepressants, have delusions and/or hallucinations, often not reported to the clinician (Dubvosky, 1991). Patients with these characteristics tend to respond poorly to TCAs when administered in monotherapy.

SSRIs and NARI are similarly ineffective. Major depressive episodes with psychotic features tend to respond to ECT on the short-term (Buchan et al, 1992; Petrides et al, 2001). The efficacy of ECT on the long-term is still controversial (O‟Leary, Lee, 1996; Spiker et al, 1985; Sackeim, 1996; Howland 2006). In a open-label community setting study, Prudic et al. (2004) found that remission rates for full courses of ECT ranged from 30.3% to 46.7% and relapses were more frequent in patients with psychotic major depression.

3

In the N.I.M.H. Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression study, response to TCAs was significantly different, when patients with psychotic major depression, moderate non-psychotic depression, and non-psychotic severe depression, were treated. The severity of the depressive episode rather that the presence of psychotic symptoms was the most important predictor of response to TCAs (Rice et al, 1989).

Patients with psychotic major depression may show a good response to a combination of TCAs and antipsychotics (Schatzberg, Rothschild, 1992, Zanardi et al, 1996, 1998, 2000).

Olanzapine in monotherapy or in combination with fluoxetine has been tested in 2 separate 8-weeks double-blind studies. In the first study, the group receiving the combination therapy had greater improvement compared to the placebo group. In the second study, there were no significant differences in clinical outcome (Rothschild et al., 2004).

The hypothesis of a distinct subtype of depression characterized by the presence of psychotic symptoms may be also supported by the identification of specific biological markers such as the activation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal Axis (HPA) (Anton, 1987; Nelson, Davis, 1997; Rothschild et al, 1982; Schatzberg et al, 1983).

Patients with psychotic depression show: a) high rates of non-suppression on the dexamethasone suppression test (DST); b) elevated post-dexamethasone cortisol levels; c) high levels of 24-h urinary free cortisol.

The HPA Axis activity does not correlate with episode severity but does correlate with the presence of psychotic symptoms (Brown et al, 1988; Evans, Nemeroff, 1983).

4

Recently, Keller and colleagues (2006) found that patients with depression and psychotic features showed higher baseline cortisol levels in the evening.

Furthermore, Rothschild et al. (1982) compared post-dexamethasone cortisol levels in patients with psychotic MDEs, schizophrenia and in healthy controls during the afternoon, and they found higher afternoon cortisol levels only in patients with psychotic MDEs. The interpretation of this finding was that the high cortisol levels correlated with the presence of psychotic symptoms in the context of an affective disorder.

Psychotic major depression is also associated with significantly higher levels of unconjugated plasma dopamine, before and after the administration of dexamethasone. Moreover, MDEs with psychotic symptoms are characterized by a significant decrease in serum dopamine-beta-hydroxylase activity (Sapru et al, 1989).

As shown above, psychotic major depression appears to be a distinct subtype of depression with specific biological characteristics often associated with greater overall illness severity. Furthermore, psychotic depressed patients tend to have higher rates of illness chronicity, relapse, and psychiatric hospitalization, as well as a poorer response to standard treatments for depression and often require adjunctive antipsychotic medications or ECT.

Given the problem of treatment and prognosis in psychotic major depression, improvements in the identification of these patients are of paramount importance.

Unfortunately, psychotic major depression can be difficult to identify because (a) psychotic features in mood disorders can be more subtle than those found in patients

5

with primary psychotic disorders, (b) patients often underreport psychotic symptoms because of embarrassment or paranoia, (c) clinicians frequently fail to fully assess for the presence of psychotic symptoms in patients with mood disorders.

Previous research has failed to systematically explore psychotic symptoms other than the presence/absence of delusions and hallucinations in major depression. More importantly, attenuated psychotic symptoms may be detectable even before the full blown psychotic phenomenology in the context of depression and its identification would allow clinicians to prevent a more severe course of illness especially when treating first episodes.

The development of novel classification schemas for psychiatric disorders aims at integrating categorical diagnoses with dimensional features, defining dimensions as discrete clusters of symptoms distributing across categories in a continuum. In this perspective, the psychotic dimension can be detected with various degrees of expression from the general population to major psychoses along the psychotic spectrum.

6

In this study we assessed the psychotic dimension in a population of patients with non-psychotic major depressive disorder by means of the MOODS-SR self reported questionnaire.

The aims of the study were:

1. to detect subthreshold lifetime psychotic phenomenology in a sample of patients with non psychotic major depressive episode, assessed by means of the MOOD-SR questionnaire.

2. to examine the “psychotic continuum” using a non-clinical sample

3. to explore possible associations among psychoticism dimension and other mood dimensions, either in the depressive or in the manic component.

4. to explore possible associations among psychoticism dimension and other dimensions such as those assessed by anxiety spectrum instruments.

5. to explore possible associations between psychoticism dimension after remission (residual phenomenology) of a major depressive non psychotic episode.

6. further, to test the “lifetime mood-anxiety model spectrum approach” for the study of the psychopatological complexity of depression.

7. to explore possible associations between the psychoticism dimension and personality traits.

8. to examine possible associations between the psychoticism dimension and quality of life and psychosocial functioning

7 Methods

Participants

Subjects were 291 individuals who met criteria for DSM-IV-TR for non-psychotic MDD, recruited in the context of a larger treatment-response trial carried out at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic of the University of Pittsburgh and the outpatient psychiatric clinic of the Santa Chiara Hospital of the University of Pisa (Depression and The Search for Treatment-relevant Phenotypes) (Frank et al, 2009, in press).

The study enrolled patients between 18 and 66 years of age and a HRSD score>=15. In the beginning of the acute phase, participants were randomly assigned to a treatment sequence that began with pharmacotherapy (SSRI – escitalopram) or interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) and received the augmentation with the second treatment if they did not respond to the first treatment. When remission was achieved, subjects entered a 6-month continuation phase and received the same treatment that lead to stabilization.

Individuals who had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I or II disorder, anorexia or bulimia, or met criteria for antisocial personality disorder or current alcohol or substance abuse in the past 3 months were excluded from the study. Individuals with severe, uncontrolled medical illnesses, those who had been unresponsive to an adequate trial of escitalopram or interpersonal psychotherapy in the current episode and women who were unwilling to practice an acceptable form of birth control were also excluded.

8

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh and the Ethics Committee of the University of Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria of Pisa. All patients signed a written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study and having an opportunity to ask questions. The study design and protocol are described in detail in previous papers (Frank et al., 2008 Benvenuti et al., 2008).

Instruments

Study participants were administered the MOODS-SR, that includes 161 items coded as present/absent, for one or more periods of at least 3 to 5 days in the lifetime. For some questions exploring temperamental features or the occurrence of specific events, the duration is not specified because it would not be applicable. Items are organized into 3 manic/hypomanic and 3 depressive domains exploring mood, energy, and cognition, plus a domain that explores disturbances in rhythmicity (e.g., changes in mood, energy, and physical well-being according to the weather, the season, and the phase of menstrual cycle) and vegetative functions (including sleep, appetite and sexual function). The sum of the scores on the 3 manic/hypomanic domains constitutes the “manic component” (62 items) and that of the 3 depressive domains the “depressive component” (63 items). The rhythmicity and vegetative functions domain includes 29 items.

Two factor analyses of the depressive and manic components of the lifetime MOODS-SR spectrum identified 6 depressive factors and 9 manic-hypomanic factors (Cassano et al, 2008 ; Cassano et al, 2009): “Depressive mood”, “Psychomotor retardation”,

9

“Suicidality”, “Drug/illness-related depression”, “Psychotic features” and

“Neurovegetative symptoms”. The factors of mania/hypomania are: “Psychomotor

Activation”, “Creativity”, “Mixed Instability”, “Sociability/Extraversion”,

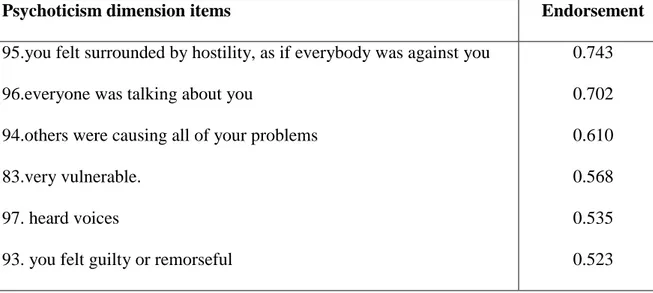

“Spirituality/Mysticism/Psychoticism”, “Mixed Irritability”, “Inflated self-esteem”, “Euphoria” and “Wastefulness/Recklessness”. For the aim of the present study, we focused on the psychotic features factor that includes the items shown in table 1. In order to better describe our working hypotesis we named the factor “psychoticism dimension”

Three lifetime self-report anxiety spectrum instruments were also administered: the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum (PAS-SR; Shear et al., 2001); the Social Anxiety Spectrum (SHY-SR; Cassano et al.,1999); the Obsessive Compulsive Spectrum (OBS-SR; Dell‟Osso et al., 2000).

The lifetime PAS-SR consists of 114 items coded as present or absent items for one or more periods of at least 3 to 5 days in the lifetime. The factor analysis of the lifetime PAS-SR has identified 10 factors: „panic symptoms‟, „agoraphobia‟, „claustrophobia‟, „separation anxiety‟, „fear of losing control‟, „drug sensitivity and phobia‟, „medical reassurance‟, „rescue object‟, „loss sensitivity‟, „reassurance from family members‟ (Rucci et al., 2009).

At the beginning of the continuation phase, patients again completed the MOODS-SR, the PAS-SR, the SHY-SR and the OBS-SR in order to assess respectively mood and anxiety spectrum symptoms occurring in the last month.

The spectrum instruments can be downloaded from the web site

10

Clinical variables as duration of illness, age at onset of depression, number of depressive episodes (coded as single episode vs. recurrent depression), history of suicide attempts (coded as present or absent), family history for psychiatric disorders (codes as present or absent) were collected at baseline.

Personality assessment was carried out by means of the SCID-II structured interview.

Quality of life and functioning were assessed using the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q) (Endicott et al., 1993; Rucci et al., 2007) and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) (Mundt et al., 2002), at baseline. The WSAS consists of 5 items rated on an 8-point ordinal scale. The total score is obtained as the sum of the 5 items and ranges from 0 to 40. The Q-LES-Q is a self-report measure of the degree of enjoyment and satisfaction experienced in 8 areas, including physical health/activities, feelings, work, household duties, school/course work, leisure time activities, social relations, general activities. The 3 areas of work, household duties and school/course work are filled out by the respondent only if applicable. Items are rated on a 5-point scale. Higher scores denote higher levels of satisfaction. Two items explore medication satisfaction and life satisfaction and contentment over the last week. The total score is the sum of the first 14 items and is expressed as a percentage of the total score of 70.

Severity of depression was rated using the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS-17; Hamilton et al.,1960).

11 Statistical analyses

In order to identify the optimal cut off within the psychoticism dimension, we performed a preliminary analysis on a separate sample of 249 patients with unipolar disorder (% F 83.9, mean age=38.0, SD=12.2) and 306 with bipolar disorder (%F 61.4, mean age=45.5, SD=14.8) recorded in the Italian and US spectrum project database. Using ROC analysis, we identified on this dataset the optimal psychotic dimension threshold discriminating unipolar from bipolar patients: (4 items endorsed; sensitivity = 60.2%, specificity = 58.2%, area under ROC curve = 0.62, CI: 0.57-0.67).

We subsequently used the instrument on a sample of unipolar patients as described in the method section above.

Participants were split into low score psychoticism dimension (<4), which we named LP and high score psychoticism dimension (≥4), which we named HP.

Chi-square test or T-test were used, as appropriate, to compare the two groups on clinical variables and one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), controlling for HDRS-17, was performed to compare the mean scores of the self-report spectrum instruments at two time points:baseline lifetime and beginning of the continuation phase .

In order to further understand the associations with spectrum dimensions, we used Psychoticism as a continuous variable.

12

Stepwise linear regression analysis was carried out to analyze the relationship between psychoticism dimension and the factors of the MOODS-SR components and the PAS-SR factors.

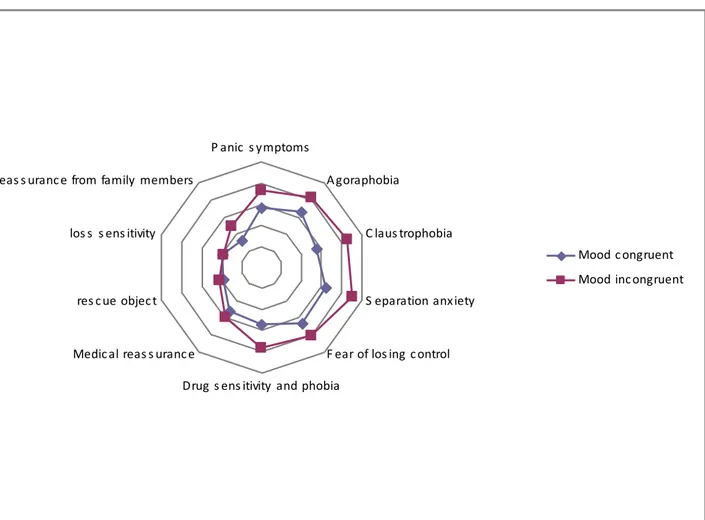

When considering the single psychoticism dimension items coded as “mood-congruent” and “mood incongruent”, Pearson‟s coefficient was performed to assess correlation with the factors of the MOODS-SR components and the PAS-SR factors.

To verify the continuum hypothesis of a normal distribution of the psychotic dimension in clinical and non-clinical populations we analyzed the frequencies of the psychoticism dimension, as assessed by means of the lifetime MOODS-SR in a sample of control healthy subjects (N=102, mean age= 30.4±9; 64.7% female) recorded in the database for the instrument validation.

All statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS, version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago 2007).

13 Results

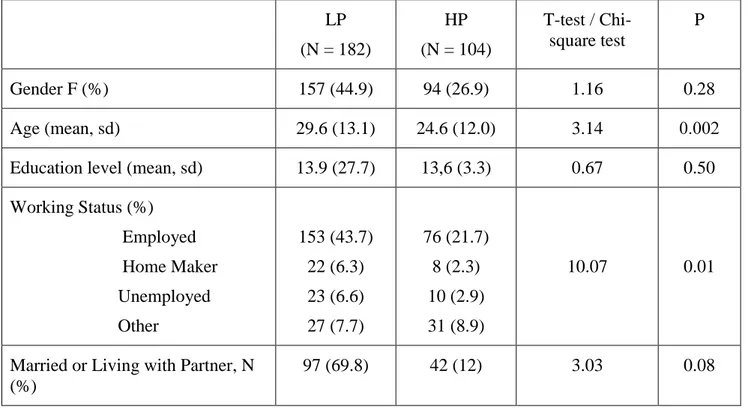

Of the 291 study participants, 286 (% F 71.7, mean age=39.6, SD=12.0) filled out the MOODS-SR at baseline. Mean lifetime scores on psychotic features were 2.8±1.5 (and mean last-month scores were 2.1±1.4). Using the cut-off score of 4, derived from ROC analysis, LP subjects were182 (63,6%) and HP were 104 (36.3%). Demographic characteristics of the two groups are described in table 2.

Psychoticism dimension and clinical variables

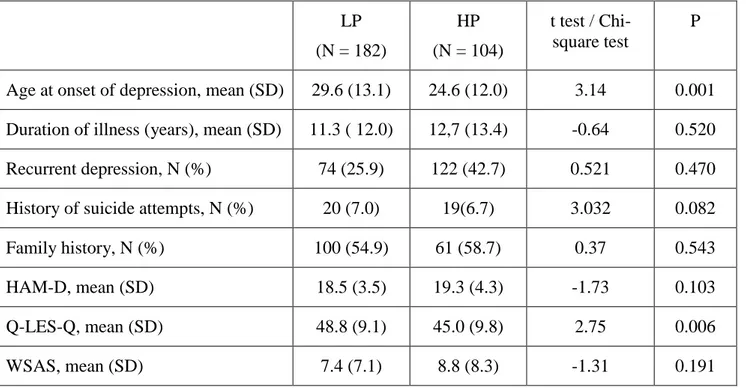

HP subjects have an earlier onset of depressive illness and a lower quality of life; but not differences were found in duration of illness, recurrence of depression, history of suicide attempts and mean baseline HAM-D scores, familiarity and functional impairment in the 2 groups. (Table 3).

Age of onset, also, was significantly earlier in patients with high psychoticism dimension and high mania/hypomania (measured using the cut-off of 22 of the MOODS-SR manic/hypomanic component) (22.2±9.9 vs 29.1±13.3, p<0.001)

High and Low psychoticism dimension in mood and anxiety spectra.

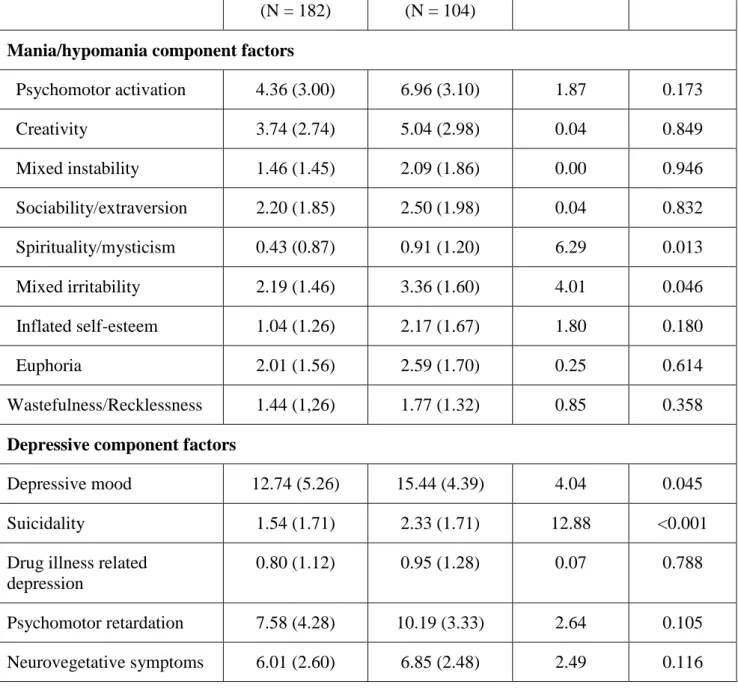

Using ANCOVA, MOODS-SR and PAS-SR factors were compared between HP and LP subjects, controlling for baseline severity of depression.

Depressive mood (F=4.04, p=0.045) and suicidality (F=12.88, p<0.001) factors mean scores of the MOODS-SR depressive component were significantly higher in HP subjects. HP patients had higher spirituality/mysticism (F=6.29, p=0.013) and mixed

14

irritability (F=4.01, p=0.046) factors of the MOODS-SR manic/hypomanic component (Table 4a).

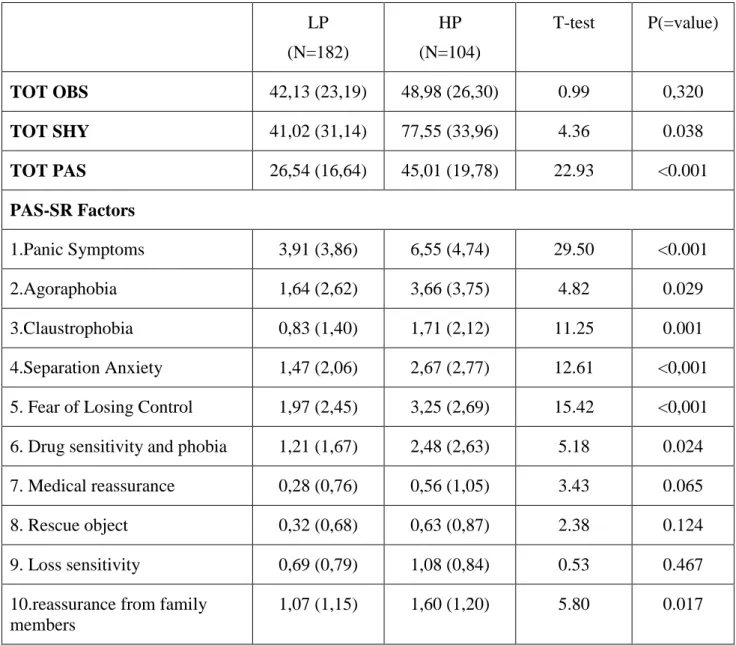

All PAS-SR factors were significantly higher in HP patients with the exception of the medical reassurance, rescue object and loss sensitivity factors. Lifetime SHY-SR total score (F=4.36, p=0.038) was significantly higher in HP patients, but no differences were found in OBS-SR total score (Table 4b).

Psychoticism dimension and residual symptoms

Of the 226 study participants who remitted from a depressive episode and entered the continuation phase of treatment, 220 filled out the MOODS-SR at baseline. Of these, 74 (33.6%) had high psychoticism dimension and 146 (66.4%) had low psychoticism dimension. Patients with higher lifetime psychoticism dimension showed more residual symptoms in all spectrum instruments, regardless of severity of depression at the beginning of the continuation phase. In particular, panic, separation anxiety, fear of losing control, drug sensitivity and phobia and claustrophobia factors of the PAS-SR were significantly higher in patients who endorsed 4 or more than 4 items of the psychoticism dimension.

HP patients showed, also, higher scores on depressive mood, psychomotor retardation and neurovegetative symptoms of the depressive component of the MOODS-SR and on psychomotor activation, inflated self-esteem and mixed irritability of the manic/hypomanic component of the MOODS-SR.

15

Association between psychoticism dimension as a continuous variable and mood and anxiety spectra.

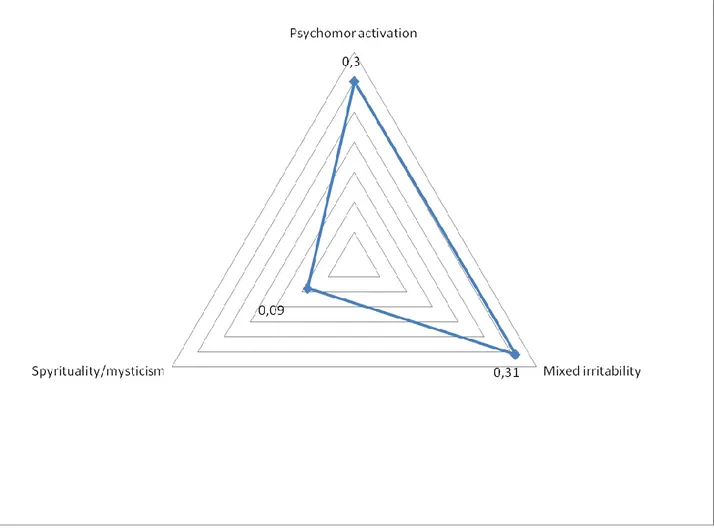

Stepwise linear regression analysis showed an association between psychoticism dimension and manic/hypomanic component factors. Standardized Beta ranged from -0.23 and 0.37. Positively associated factors were: psychomotor activation (p<0.001), mixed irritability (p<0.001) and inflated self esteem (p=0.022). Sociability/extraversion was negatively associated (p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Two factors of the depressive component were positively associated with psychoticism dimension: psychomotor retardation (beta=0.36, p<0.001) and suicidality (beta=0.18, p=0.002) (Figure 2).

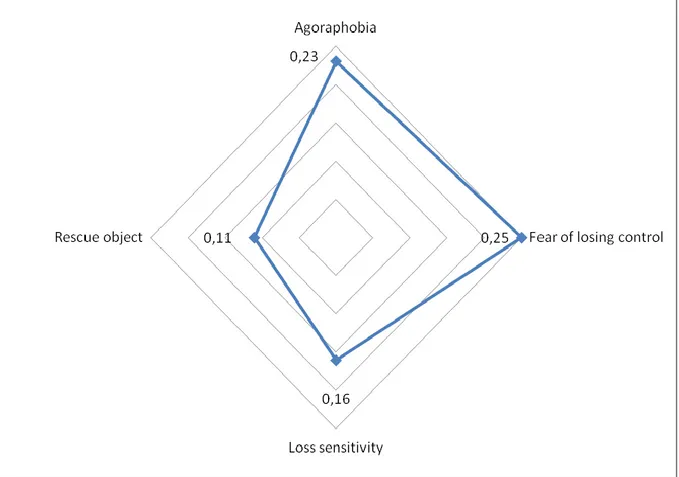

A positive association was found between agoraphobia (p<0.001), fear of losing control (p<0.001), loss sensitivity (p=0.004) and rescue object (0.045) and the psychoticism dimension with beta ranging from 0.25 to 0.11. (Figure 3)

Psychoticism dimension was also associated with SHY-SR (beta=0.57, p<0.001) and OBS-SR (beta=0.14, p=0.022).

Personality assessment

Personality assessment was compared between HP and LP subjects. Paranoid and avoidant personality disorders were overrepresented in the HP group (10.9% vs 3.3% p=0.011; 28.7% vs 11.1%, p<0.001 respectively).

16

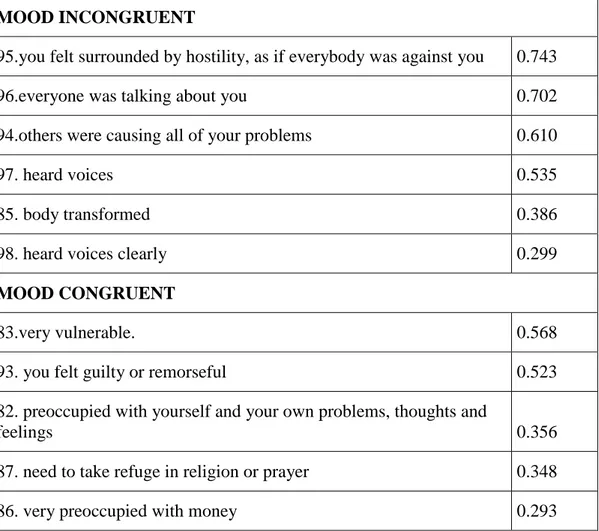

Mood-congruent and mood-incongruent psychoticism dimension

Mood-congruent and mood-incongruent items in the psychoticism dimension are shown in Table 6. In this analysis the psychoticism dimension includes also the 5 items with low loading (<0.040) (Cassano et al, 2008).

We correlated mood-congruent and mood-incongruent items with factors included in the mood and anxiety spectra. Results are shown in Figures 6-8.

The strongest correlation was found between mood incongruent items and PAS-SR factors including fear of losing control (r=0.40), agoraphobia (r=0.41), claustrophobia (r=0.43) and separation anxiety (r=0.45). The same items are weakly correlated (r<0.35) with depressive and manic/hypomanic components‟ factors.

Psychoticism in a non-clinical population

The mean score of the psychoticism dimension in 102 healthy subjects was 0.9±1.3 which is significantly lower than the mean assessed in our population of unipolar depression (t=11.34, p<0.001). Only 7 (6.9%) healthy subjects had a score above our cut-off of 4.

17 Discussion

Our study demonstrates that in a sample of unipolar non-psychotic depressed patients a lifetime psychoticism dimension can be detected.

104/286 subjects scored 4 or more than 4 on the psychoticism dimension including 6 items ranging from interpersonal sensitivity (“I felt very vulnerable”) to frank psychotic symptoms (“You heard voices”, “You felt surrounded by hostility as if everybody was against you” or “everybody was talking about you”).

In agreement with the current opinion by which symptoms distribute across categories in a continuum, the psychoticism dimension does not make an exception. In this perspective, subtle psychotic phenomenology should extend from controls to diagnosable psychotic disorders (Shevlin et al, 2007,Compton et al, 2008; Van Os, 1999, Van Os, 2000).

The question concerning the frequency of the same items in a non-clinical population confirms the continuum hypothesis. Indeed, we submitted the same instrument (MOODS-SR) to a sample of 102 healthy controls and we found that only 6.9% of subject exceeded the cut-off of 4 (compared with 36% in our clinical sample) and that the frequency of the psychoticism dimension was significantly lower (mean 0.9±1.3).

Previous attempts to quantify the presence of psychoticism phenomenology in individuals with MDD found that 18.5% of depressed patients also presented either frank delusions or auditory hallucinations (Ohayon and Shatzberg, 2002). Our data showed a higher proportion of lifetime psychotic features in depressed patients . In a survey carried out in the Netherlands, a 24-item self-reported instrument was used to

18

assess attenuated or transient psychotic symptoms and was administered to the general population. Subjects diagnosed as having a depressive/anxious disorder, among the general population, scored in the middle between controls and individuals with diagnosis of psychosis (Van Os, 1999).

Using the psychoticism dimension as dichotomous and as continuous variable we found that patients with high psychoticism dimension displayed higher scores on lifetime depressive mood, psychomotor retardation and suicidality factors in the depressive component. Moreover, depressive mood and psychomotor retardation factors are, also, more frequent in patient with higher psychoticism dimension who achieve remission from an MDE. Suicidality, depressive mood and psychomotor retardation have been considered as markers of severity in the global depressive phenomenology, consistently with the hypothesis of psychotic depression as a more severe subtype of MDD along a continuum (Rothschild et al 1989; Charney DS, Nelson JC, 1981; Lykouras et al., 1984, Gaudiano et al., 2009; Thakur et al., 1999; Keller et al., 2007).

Within the lifetime manic/hypomanic component, high scores on spirituality/mysticism and mixed irritability factors were found in patients with high scores on psychoticism dimension.

Also, high lifetime psychoticism dimension (as continuous variable) was positively associated with lifetime and residual psychomotor activation, mixed irritability and inflated self esteem factors which represent indicators of soft bipolarity. (Akiskal, Ghaemi, Benazzi, 2004).

In the last decade the traditional unipolar/bipolar divide have been challenged by a great body of evidence giving support to a dimensional view of affective disorders (Akiskal,

19

2003; Angst et al., 2003, Cassano et al., 2004; Ghaemi et al., 2002, Angst et al., 2007) with individuals with unipolar depression experiencing a number of manic/hypomanic symptoms over their lifetimes (Cassano et al., 2004; Angst et al, 2005 ). In our sample, subjects with high lifetime psychoticism dimension and elevated lifetime manic/hypomanic features have a significantly earlier age of onset compared to the rest of the group. Age at onset proved to have a strong genetic basis (Benazzi, 1999; Merikangas, 2007) and according to recent reports, early age at onset of first major depression is superior to recurrences in identifying an MDD subgroup closer to Bipolar II Disorder (Benazzi and Akiskal, 2008).

High psychoticism dimension and high manic/hypomanic features identified a subgroup of depressed patients in our sample with significantly earlier age at onset, therefore indicating a proximity to the bipolar spectrum with potential implications for clinical management.

Interestingly, the lifetime psychoticism dimension is associated with both lifetime psychomotor retardation and activation. Indeed, in patients with higher lifetime psychoticism dimension there are more residual symptoms of psychomotor activation and retardation left. Psychomotor changes are included in the DSM-IV criteria for MDD (or traditionally to the “endogenous” form of depression) and have been shown to reliably differentiate depressive patients from psychiatric and normal comparison groups (Sobin and Sackeim, 1997). Moreover, psychomotor disturbance has been proposed as a marker of an underlying neurobiological process consistent with a potential dopaminergic dysfunction related to depression (Nestler et al 2000) and eventually a distinct clinical endophenotype. This hypothesis, which cannot be confirmed by our data, deserves further investigation.

20

In our sample, depressed patients with high lifetime psychoticism dimension, also have higher scores on PAS-SR, OBS-SR and SHY-SR questionnaires, in particular, when considering psychoticism dimension as a continuous variable, a positive association can be found with lifetime panic/agoraphobic factors such as agoraphobia, loss sensitivity, fear of losing control and rescue object.

The lifetime psychoticism dimension is associated with more residual symptoms on anxiety spectra instruments; confirming that anxious comorbidity is present in patients who apparently are in clinical remission and is an important predictor of outcome (Vieta et al., 2008).

Patients with psychotic MDD do have higher rates of multiple anxiety disorder comorbidity and panic disorder and social phobia are common, occurring either singly or in mutual association. (Pini et al. 2006, Charney et al., 1981; Lattuada, 1999; Coryell et al., 1984; Johnson et al., 1991)

Findings from several studies suggest that panic attacks and psychotic disorders co-occur more often than would be expected by chance (Goodwin et al., 2002, 2004; Galynker et al., 1996) and panic symptoms or panic disorder are significantly more prevalent among patients with psychotic major depression than among either patients with schizophrenia/ schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder with psychosis (Craig et al., 2002), however the nature of this relationship is unclear.

When we analysed the correlation between “mood congruent” and “mood incongruent” psychoticism and anxiety spectra, we found that the “mood incongruent” subgroup of items showed a stronger association with specific PAS-SR factors (fear of losing control, agoraphobia, claustrophobia and separation anxiety).

21

The nature of the association between spectrum panic symptoms and psychoticism dimension is unclear. We could speculate that anxiety has a destabilizing effect on physical, emotional and cognitive functioning leading to a vulnerability for the onset of psychotic symptoms. Perhaps patients with psychotic vulnerability report panic symptoms as delusional persecutory experiences which are rarely properly diagnosed as panic disorder. We could also speculate that psychotic symptoms and panic attacks are related by common environmental factors. Certainly this association requires clinical attention as it could have an impact on the therapeutic relationship, on psychotherapy and pharmacological treatment.

In our subjects with high psychoticism dimension, paranoid and avoidant personality disorders are overrepresented. To our knowledge this is the first study ever reporting a clear association with Axis II personality disorder.

Individuals with high psychoticism dimension (HP) had a lower quality of life but no difference was found between high al low psychoticism dimension in functional impairment.

Data about psychosocial functioning in psychotic depression in literature are sparse and possibly conflicting because of the different criteria used to recruit the clinical samples (Gaudiano et al., 2009) Goldberg and Harrow (2005) reported that functional impairment in psychotic depressed patients contributed to poorer perceived quality of life and they may have particular difficulty in acknowledging the impact of illness on functional well-being, while some other studies have reported that patients affected by psychotic depression do show a greater functional impairment over long-term follow-up (Rothschild et al., 1993; Coryell et al., 1996; Gaudiano et al., 2009).

22 Limitations

We acknowledge that the MOOD-SR does not explore the frequency of individual symptoms but only inquires whether symptoms did or did not occur for a period of at least 3-5 days in the subject‟s lifetime. As a consequence, the relationship that we found between psychotic features and other clinical factors does not imply anything about the co-occurrence or sequence of these experiences.

Moreover, since the instrument assesses symptoms and behaviours retrospectively, there might be a recall bias.

23 Conclusions

Subtreshold psychotic phenomenology is detectable in a sample of unipolar non-psychotic depressed patients using the non-psychoticism dimension of the lifetime version of the MOODS-SR. This factor contains items which span from subthreshold to frank psychotic symptoms The psychoticism dimension also distributes in a non-clinical population with a significantly lower frequency which may represent the mild end of the psychotic spectrum fading into “normality”. As previously suggested, a “psychosis continuum” implies that the same symptoms that are seen in patients with psychotic disorders can be measured in a non-clinical population (Van Os et al., 2009)

The MOODS-SR carefully assessed, in a comprehensive way, threshold and subthreshold psychoticism phenomenology, in an easy-to-use format, generally well accepted by patients and clinicians. Findings from this study suggest that the psychoticism dimension of the MOODS self-report instrument, is able to offer clinicians a refined assessment of psychopathology, even in non psychotic depression.

The evaluation of lifetime features of a complex psychopathological dimension, such as the psychoticism, requires a special clinical training and an extensive clinical experience. With the carefully-constructed, standardized assessment provided by the psychoticism dimension of the MOODS-SR, the identification of these signs and symptoms, often overlooked by clinicians, becomes a relatively easy and reliable process. Moreover, this assessment could address clinicians toward a better focus on personality disorder.

Clinicians should carefully consider (a) psychometrically-detectable subclinical lifetime experiences in the treatment of unipolar depression as expressions of potentially

24

evolving psychosis proneness if individuals became exposed to environmentally stressful life events; (b) the presence of the psychoticism dimension in unipolar depression as an indicator of higher frequency of residual symptoms in patients who achieve remission from an MDE and then of poorer long term outcome. Further studies are needed to ascertain the validity of this dimension and assess the possibility that this dimension may detect patients who transit to psychotic disorder.

25 References

Akiskal HS, The interface of affective and schizophrenic disorders: a cross between two spectra. In A. Marneros and HA Akiskal, Editors, The Overlap of affective and

Schizophrenic Spectra, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK (2007), 277-291. Akiskal HS, Walker P, Puzantian VR, King D, Rosenthal TL, Dranon M. Bipolar

outcome in the course of depressive illness. Phenomenologic, familial, and pharmacologic predictors. J Affect Disord. 1983;5:115–128.

Akiskal, H.S., 2003. Validating „hard‟ and „soft‟ phenotypes within the bipolar spectrum: continuity or discontinuity? J.Affect.Disord. 73, 1–5.

Akiskal, H.S., Maser, J.D., Zeller, P.J., Endicott, J., Coryell,W., Keller, M., Warshaw, M., Clayton, P., Goodwin, F., 1995. Switching from „unipolar‟ to bipolar II. An 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental predictors in 559 patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 52, 114–123.

Allardyce T, Suppes and J van Os, Dimensions and the psychosis phenotype, INt J Methods Psychiatr Res, 16 (2007), 34-40

American Psychiatric Association. DSM IV: Diagnostic And statistical manual of mental disorders , 1987, 4th edition.

Andreason NC . The validation of psychiatric diagnosis: new models and approaches (editorial). Am J Psychiat , 1995, 152: 161-162.

Andreescu C et al. Persisting low use of antipsychotics in the treatment of major depressive disorder with psychotic features. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007; 68: 194-200. Angst, J., 2007. The bipolar spectrum. Br. J. Psychiatry 190, 189–191.

26

Angst, J., et al., Diagnostic conversion from depression to bipolar disorders: results of a long-term prospective study of hospital admissions. J Affect Disord, 2005. 84(2-3): p. 149-57.

Angst, J., Gamma, A., Benazzi, F., Ajdacic, V., Eich, D., Rossler, W., 2003. Toward a re-definition of subthreshold bipolarity: epidemiology and proposed criteria for bipolar-II, minor bipolar disorders and hypomania. J. Affect. Disord. 73, 133–146.

Angst, J., Sellaro, R., Stassen, H.H., Gamma, A., 2005b. Diagnostic conversion from depression to bipolar disorders: results of a longterm prospective study of hospital admissions. J. Affect. Disord. 84, 149–157.

Anton RF. Urinary free cortisol in psychotic depression: a meta-analysis. Am J psychiatry, 1997; 154: 1497-1503.

Balzer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, swatz MS. the prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychitry. 1994; 151. 979-986.

Benazzi F, Akiskal HS. Continuous distribution of atypical depressive symptoms between major depressive and bipolar II disorders: dose-response relationship with bipolar family history. Psychopathology, 2008; 41 (1): 39-42.

Benvenuti a, Rucci P, Miniati M, Papasogli A, Fagiolini A, Cassano GB, Swartz H, Frank E. Treatment-emergent mania/hypomania in unipolar patients. Bipolar disord 2008, Sep;10(6):726-32.

Birkenhager TK, Reense JW, Pluijms EM. One-year follow-up after successful TEC: a naturalistic study in depressed inpatients. J ECT, 2004; 65: 87-91.

27

Birkenhager TK, van den Broek WW et al. One year outcome of psychotic depression after successful TEC. J ECT, 2005; 21:221-226.

Black DW, Winokur G, Bell S, Nasrallah A, Hulbert J: Complicated mania: comorbidity and immediate outcome in the treatment of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:232–236

Black DW, Winokur G, Nasrallah A. Effect of psychosis on suicide risk in 1593

patients with unipolar and bipolar affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1988; 145: 849-852.

Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Rozal GP, Florio L, Hoff RA: Psychiatric status and 9-year mortality data in the New Heaven Epidemiologic catchment area Study. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151: 716-721.

Buchan H, Johnstone E, McPherson K et al. Who benefits from electroconvulsive therapy?Combined results of the Leicester and Northwock Park trials. Br J Psychiatry, 1992; 160: 355-359.

Cassano GB, Benvenuti A, Miniati M, Calugi S, Mula M, Maggi L, Rucci P, Fagiolini A, Perris F, Frank E. The factor structure of lifetime depressive spectrum in patients with unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2008 Oct 21.

Cassano GB, dell'Osso l, Frank E. The bipolar spectrum: a clinically reality in search pf diagnostic criteria and an assessment methodology. J Affect Disord. 1999, 54: 319-328. Cassano GB, Frank E et al. Conceptual underpinnings and empirical support for the

28

Cassano GB, Mula M, Rucci P, Miniati M, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Oppo A, Calugi S, Maggi L, Gibbons R, Fagiolini A. The structure of lifetime manic-hypomanic spectrum. J Affect Disord. 2009 Jan;112(1-3):59-70.

Cassano GB, Pini S, Saettoni M, Rucci P, Dell‟Osso L: Occurrence and clinical correlates of psychiatric comorbidity in patients with psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:60–68

Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and public health: an overview. J Psychosom Res, 2002, 53: 849-857.

Cassano, G.B., Rucci, P., Frank, E., Fagiolini, A., Dell'osso, L., Shear, M.K., Kupfer, D.J., 2004. The mood spectrum in unipolar and bipolar disorder: arguments for a unitary approach. Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 1264–1269.

Charney DS, Nelson JC. Delusional and non delusional unipolar depression: further evidence for distinct subtypes. Am J Psychiatry. 1981; 138: 328-333.

Charney DS, Nelson JC. Delusional and nondelusional unipolar depression: further evidence for distinct subtypes. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138:328–333.

Compton MT, Carter T, Kryda A, Goulding SM, Kaslow NJ. The impact of psychoticism on perceived hassles, depression, hostility, and hopelessness in non-psychiatric African Americans. Psychiatry Res. 2008 May 30;159(1-2):215-25. Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller M, Andreasen N. Phenomenology and family history in

DSM-III psychotic depression. Journal of affective disorders. Vol. 9, 1, 1985, 13-18. Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller M. The importance of psychotic features to major

depression : course and outcome during a 2-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 1987; 75: 78-85.

29

Coryell W, Leon A, Winokur G, et al. Importance of psychotic features to long-term course in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:483–489.

Coryell W, Pfohl B, Zimmerman M. The clinical and neuroendocrine features of psychotic depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 1984;172:521–528.

Coryell W, Tsuang MT, McDaniel J. Psychotic features in major depression. Is mood congruence important? J Affective Disorder 1982 Sep;4(3):227-36.

Coryell W, Tsuang MT. Major depression with mood-congruent or mood-incongruent psychotic features: outcome after 40 years. Am J Psychiatry, 1985 Apr;142(4):479-82. Coryell W. Psychotic depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:27–31.

Craig T, M.D., Hwang MY, Bromet EJ. Obsessive-Compulsive and Panic Symptoms in Patients With First-Admission Psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:592–598

Dell'Osso L, Cassano GB, Sarno N, Millanfranchi A, Pfanner C, Gemignani A, Maser JD, Shear MK, Grochocinski VJ, Rucci P, Frank E. Validity and reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum (SCI-OBS) and of the Structured Clinical Interview for Social Phobia Spectrum (SCI-SHY) Int J Meth Psych Res 9:11-24, 2000

Drebets WC, Funciotnal anatomical abnormalities in limbic and prefrontal cortical structures in major depression. Prog Brain Res. 2000; 126: 413-31.

Drevets WC:Subgenual prefrontal cortex volumes in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia: diagnostic specificity and prognostic implications.

Dubovsky SL. What we don't know about psychotic depression. Bio Psychiatry. 1991; 30: 533-536.

30

Eaton W, Romanoski JC, Nestadt G. Screening for psychosis in the general population with a self-report interview. J Nerv Ment Dis. , 179 (1991): 689-693.

Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R., 1993. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 29, 321-6.

Evelyn J. Bromet, Ph.D. Obsessive-Compulsive and Panic Symptoms in Patients With First-Admission Psychosis Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:592–598

Fennig S, Bromet EJ, Tanenberg KM, Ram R, Jandorf L. Mood-congruent versus mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms in first-admission patients with affective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 12 February 1996, Pages 23-29

Frances A, Brown RP, Kocsis JH, Mann JJ: Psychotic depression: a separate entity? Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138: 831-833.

Frangos E, Athanassenas g, Tsitourides S, Psilolignos P, Katsanou N: Psychotic depressive disorder: a separate entity? J Affect Disord 1983, 5: 259-265.

Frank E, Cassano GB, Rucci P, Fagiolini A, Maggi L, Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ, Pollock B, Bies R, Nimgaonkar V, Pilkonis P, Shear MK, Thompson WK, Grochocinski VJ, Scocco P, Buttenfield J, Forgione RN. Addressing the challenges of a cross-national investigation: lessons from the Pittsburgh-Pisa study of treatment-relevant phenotypes of unipolar depression. Clin Trials. 2008;5(3):253-61.

Galynker I, Ieronimo C, Perez-Acquino A, Lee Y, Winston A: Panic attacks with psychotic features. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:402–406

Gaudiano BA et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of psychotic versus nonpsychotic major depression in a general psychiatric outpatient clinic. Depress anxiety, 2008, 9 (26): 54-64.

31

Gaudiano BA, Young D, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Depressive symptom profiles and severity patterns in outpatients with psychotic vs nonpsychotic major depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2008 Sep-Oct;49(5):421-9.

Gershon ES, Hamovit J, Guroff JJ et al: a family study of schizoaffective, bipolar I, bipolar II, unipolar and normal control probands. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39.1157-1167.

Ghaemi, S., Ko, J., Goodwin, F., 2002. “Cades Disease” and beyond: misdiagnosis, antidepressant use, and a proposed definition for bipolar spectrum disorder. Can. J. Psychiatry 47, 125–134.

Ghaemi, S.N., Hsu, D.J., Ko, J.Y., Baldassano, C.F., Kontos, N.J., Goodwin, F.K., 2004. Bipolar spectrum disorder: a pilot study. Psychopathology 37, 222–226.

Giovanni B. Cassano, M.D., F.R.C.Psych., Stefano Pini, M.D., Ph.D., Marco Saettoni, M.D., and Liliana Dell‟Osso, M.D. Multiple Anxiety Disorder Comorbidity in Patients With Mood Spectrum Disorders With Psychotic Features Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:474–476)

Glassman AH, Roose SP, Delusional depression: a distinct clinical entity? Arch gen Psychiatry. 1981; 38:424-427.

Goldberg JF, Harrow M. Subjective life satisfaction and objective functional outcome in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders: longitudinal analysis. J Affect Disord 2005;89:79– 89.

Goodwin RD, Davidson L: Panic attacks in psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 105:14–19

32

Gruzelier JH (1996). The factorial structure of schizotypy. Part I. Affinities with syndromes of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22, 611–620.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960 Feb;23:56-62.

Howland RH. Pharmacotherapy for psychotic depression. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2006; 24: 365-373.

Jenkins R, Lewis G, Bebbington p, et al. The National Psychiatric Mordibity surveys of Great Britain-initial findings from the household survey. Psychol Med. 1997; 27: 775-789.

Johnson J, Horwath E, Weissman M. The validity of major depression with psychotic features based on a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:1075–1081. Jorm AF, Henderson AS, Kay DWK, Jacomb PA: Mortality in relation to dementia,

depression and social integration in an elderly community sample. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1991; 6:5-11.

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Paulus M. The role and clinical significance of subsyndromal depressive symptoms (SSD) in unipolar major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord, 1997, 45: 5-18.

Kantor SJ, Glassman AH: Delusional depressions: natural history and response to treatment). Br J Psychiatry 1977; 131:351-360.

Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Solomon DA. Realistic expectations and a disease management model for depressed patients with persistent symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry, 2006, 67: 1412-1421.

33

Keller J, Gomez RG, Kenna HA, et al. Detecting psychotic major depression using psychiatric rating scales. J psychiatr Res. 2006; 40: 22-29.

Kendell R, Jablensky A. Distinguishing between the validuty and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2003; 160: 4-12.

Kendler KS, Gardner CO Jr. Boundaries of major depression: an evaluation of DSM-IV criteria. Am J Psychiatry, 1998; 155: 172-177.

Kennedy SH, Giacobbe P. Treatment resistant depression advances in somatic therapies. Ann Clinn Psychiatry, 2007, 19: 279-287.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age of onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):593-602. Koenig Hg, Shelp f, Goli V, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG: Survival and health care utilization

in elderly medical inpatients with major depression. J Am Geriatri Soc 1989, 37:599-606.

Lataster T, Myin-Germeys I, Derom C, Thiery E, van Os J. Evidence that self-reported psychotic experiences represent the transitory developmental expression of genetic liability to psychosis in the general population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 Feb 19.

Lattuada E, Serretti A, Cusin C, Gasperini M, Smeraldi E. Symptomatologic analysis of psychotic and non-psychotic depression. J Affect Disord 1999;54:183–187.

Leckman JF, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, et al. Subtypes of depression. Family study perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:833–838.

34

Lewandowski KE, Barrantes-Vidal N, Nelson-Gray RO, Clancy C, Kepley HO, Kwapil TR (2006). Anxiety and depression symptoms in psychometrically identified schizotypy. Schizophrenia Research 83, 225–235.

Lykouras E, Malliaras D, Christodoulou Gn et al. Delusional depression:

phenomenology and response to treatment, a prospective study. Acta Psychiatr Scnad, 1986; 73: 324-329.

Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Bartoli L. Phenomenology and prognostic significance of delusions in major depressive disorder: a 10-year follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry, in press.

Mata I, Gilvarry CM, Jones PB, Lewis SW, Murray RM, Sham PC (2003). Schizotypal personality traits in nonpsychotic relatives are associated with positive symptoms in psychotic probands. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29, 273–283.

Mo¨ller H-J (2005) Antipsychotic and antidepressive effects of second generation antipsychotics. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (Special Issue) 255:190–201 Mowbray RM. The Hamilton rating Scale for Depression: a factor analysis . Psychol

Med, 1972, 2, 271-80.

Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH., 2002. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 180, 461-4 Murphy E, Smith R, Lindesay J, Slattery J: Increased mortality rates in late-life

depression. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:347-353.

Nelson JC, Bowers MB Jr. Delusional unipolar depression: description and drug response. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978; 35: 1321-1328.

35

Nelson JC, Charney DS (1981) Delusional and non delusional unipolar depression: further evidence for distinct subtype. Am J Psychiatry. 1981 Mar;138(3):328-33 Nelson JC, Davis JM. DST studies in psychotic depression: a a meta-analysis. Am J

Psychiatry. 1997; 154: 1497-1503.

Nelson WH, Khan A, Orr WW Jr: Delusional depression: phenomenology,

neuroendocrine function and tricyclic antidepressant response. J affect Disord 1984; 6:297-306.

Oakley-Browne MA, Joyce PR, Wells JE, Bushnell JA, Hornblow AR. Christchurch Psychiatric Epidemiologic Studi, Part II: six month and other period prevalences of specific psychiatric disorders. Aust n Z J Psychiatry. 1989; 23: 327-340.

O'Brien KP, Glaudin V. Factorial structure and factor reliability of the HAM-D. Acta Psych Scand, 1988, 78: 113-120.

Ohayon MM, Schatzberg AF, Am J psychiatry 2002; 159: 1855-1861. Prevalence of depressive episodes with psychotic features in the general population.

O'Leary DA, Lee AS. Seven year prognosis in depression. Mortality and readmission risk in the Nottingham ECT cohort. Br J Psychiatry . 1996; 169: 423-429.

Overall JE, Gorham DE. The brief psychiatric rating sdcale. Psychol Rep. 1961; 10: 799-812.

Parker G, Hadzi.Pavlovic D et al. Distinguishing psychotic and non-psychotic melancholia. Journal of affective dis., 1991, 22: 135-148.

Petrides G, Fink M, Husain MM et al. ECT remission rates in psychotic versus nonpsychotic depressed patients: a report from CORE. J ECT, 2001; 17: 244-253.

36

Phelps JR, Ghaemi N.Improving the diagnosis of bipolar disorder: predictive value of screening tests. Journal of Affective disorders, 92 (2006): 141-148.

Prudic J, Olfson M, Marcus SC, Fuller RB, Sackeim HA. Effectiveness of TEC in community settings. Bio Psychiatry. 2004; 55: 301-312.

Pulska T, Pahkala K, Laippalla P, Kivela SL: Major depression as a predictor of

premature deaths in elderly people in Finland: a community study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 97:408-11.

Rabins PV, Harvis K, Koven S: High fatality rates of late-life depression associated with cardiovascular disease. J affect disord 1985; 9:165-67.

Rassmussen KG, Mueller M, Kellner CH et al. Patterns of psychotropic medication use among patients with severe depression referred for ECT: data from the consortium for research on ECT. J ECT. 2006, 22: 116-123.

Regier DA, Kaelber CT, Rae DS, et al. Limitations of diagnostic and assessment instruments for mental disorders. Arch Gen Psych. , 1998, 55: 109-115.

Renee D. Goodwin, Ph.D., M.P.H. David M. Fergusson, Ph.D., John Horwood, M.Sc. Panic Attacks and Psychoticism. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:88–92

Romera I et al. Factor analysis of the Zung self Rating depression scale in patients with major depressive disorder in primary care. BMC Psych, 2008, 8,4.

Roose SP, Glassman AH, Walsh BT, Woodring S, Vital-Herne J: Depression, delusions and suicide. Am J psychiatry 1983; 140: 1159-1162.

Rothschild AJ, Samson JA, Bond TC, Luciana MM, Schildkraut JJ, Schatzberg AF. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity and 1-year outcome in depression. Biol Psychiatry 1993;34:392–400.

37

Rothschild AJ, Samson JA, Schildkraut JJ, Cole JO, Schatzberg AF, Langlais PJ: Biochemical abnormalities in psychotic depression, in CME Syllabus and scientific

Proceedings in Summary Form, 142nd Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric

Association. Washington, DC, APA, 1989.

Rothschild Aj, Schatzberg AF, Rosenbaum AH, Stahl JB, Cole JO. The DST suppression test as a discriminator among subtypes of psychotic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1982, 141: 471-474.

Rothschild AJ, Williamso DJ, Tohen MF et al. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. J Clin Psychopharmacol.2004; 24:365-373.

Rothschild AJ. Challlenges in tre treatment of depression with psychotic features. Biol Psychiatry. 2003; 53: 680-690.

Rothschild AJ. Management of psychotic, treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;19:237–252.

Rucci P, Rossi A, Mauri M, Maina G, Pieraccini F, Pallanti S, Camilleri V, Montagnani MS, Endicott J., 2007. Validity and reliability of Qualità of Life, Enjoyment and

Satisfaction Questionnire, Short Form. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 16, 82-9 Rush AJ. The varied clinical presentations of major depressive disorder. J Clin

Psychiatry, 2007, 68: 4-10.

Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP et al. The impact of medication resistance and continuation pharmacotherapy on relapse following response to TEC in major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol . 1990; 10; 96-104.

38

Sapru MK, Rao BS, Channavanna SM. Serum dopamine-beta.hydroxylase activity in clinical subtypes of depression. Acta Psych Scand. 1989; 80: 474-478.

Schatzberg AF, Rothschild AJ Psychotic (delusional) Major depression: should it be included as a distinct syndrome in DSM-IV? Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149: 733-745. Schatzberg AF, Rothschild AJ, Stahl JB et al. The DST suppression test: identification

of subtypes of depression. Am J psychiatry. 1983. 140:88-91.

Schrijvers D et al. Psychomotr symptoms in depression: a diagnostic, pathophysiological and therapeutic tool. J Affect Disord, 2008, 109: 1-20.

Schulze TG, Ohlraum S, Czerski PM, Schumacher J, Kassem I, Deschner M, Gross M, Tullius M, Heidman V, Kovalenko S, Jamra RA, Becker T, Leszcynska-Rodziewicz A, Hauser J, Illig T, Klopp N, Wellek S, Chichon S, Henn FA, McMahon FJ, Maier W, Propping P, Nothen MM, Rietschel M (2005) Genotype studies in bipolar disorder showing association between the DAOA/G30 locus and persecutory delusions: a first step toward a molecular genetic classification of psychiatric phenotypes. Am J Psychiatry 162:2101–2108

Serretti A, Lattuada E, Cusin C, Gasperini M, Smeraldi E. Clinical and demographic features of psychotic and nonpsychotic depression. Compr Psychiatry. 1999 Sep-Oct;40(5):358-62.

Serretti A, Lattuada E, Cusin C, Gasperini M, Smeraldi E. Clinical and demographic features of psychotic and nonpsychotic depression. Compr Psychiatry 1999;40:358– 362.

Serretti A, Olgiati P. Profiles of "manic" symptoms in bipolar I, bipolar II and major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord, 2005, Feb;84(2-3):159-66

39

Shear MK, Frank E, Rucci P et al. Panic-agoraphobic spectrum: reliability and validity of assessment instruments. J Psychiatr Res, 2001, Jan-Feb; 35 (1): 59-66.

Shevlin M, Murphy J, Dorahy MJ, Adamson G. The distribution of positive psychosis-like symptoms in the population: a latent class analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. Schizophr Res. 2007 Jan;89(1-3):101-9.

Spauwen J, Krabbendam L, Lieb R, Wittchen HU, van Os J. Evidence that the outcome of developmental expression of psychosis is worse for adolescents growing up in an urban environment. Psychol Med. 2006 Mar;36(3):407-15.

Spiker DG, Stein J, Rich CL. Delusional depression and ECT: one year later. Convuls Ther. 1985; 1: 167-172.

Spiker DG, Weiss JC, Dealy RS, Griffin SJ, Hanin I, Neil JF, Perel JM, Rossi AJ, Soloff PH: The pharmacological treatment of delusional depression. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142: 430-436.

Stefanis N, Hanssen M, Smirnis N, Avramopoulos D, Evdokimidis I, Stefanis CN, Verdoux H, van Os J (2002) Evidence that three dimensions of psychosis have a distribution in the general population. Psychol Med 32:347–358

Strakowsky SM, Tohen M, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Goodwin DC: Comorbidity in mania at first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:554–556

Strakowsky SM, Tohen M, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Mayer PV, Kolbrener ML, Goodwin DC: Comorbidity in psychosis at first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:752– 757

40

Strober M, Carlson G. Bipolar illness in adolescents with major depression: clinical, genetic, and psychopharmacologic predictors in a three- to four-year prospective follow-up investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:549–555.

Thakur M, Hays J, Kishnan K. Clinical, demographic and social characteristics of psychotic depression. Psychiatry Res 1999; 86:99–106.

Thakur M, Hays J, Kishnan K. Clinical, demographic and social characteristics of psychotic depression. Psychiatry Res 1999; 86:99–106.

Thase ME, Kupfer DJ, Ulrich RF. Electroencephalographic sleep in psychotic depression. A valid subtype? Arch Gen Psychiatry, 1986; 43: 886-893.

van Os J, Hanssen M, Bijl RV, Ravelli A. Strauss (1969)revisited: a psychosis continuum in the general population? Schizophr Res. 2000 Sep 29;45(1-2):11-20. Van Os J, Verdoux H, Maurice-Tison S, Gay B, Liraud F, Salamon R, Bourgeois M

(1999) Self-reported psychosis-like symptoms and the continuum of psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 34:459–463

Vanehuele S et al. The factor structure of the Beck Depression Inventory II: An evaluation. Assessment. 2008, Jan 8.

Verdoux H, van Os J. Psychotic symptoms in non-clinical populations and the continuum of psychosis. Schizophr Res 2002;54:59–65.

Vieta E., Sanchez-Moreno L et al. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar and unipolar disorder during clinical remission.J Affect Disord., 2008

41

Vollema MG, Hoijtink H (2000). The multidimensionality of self-report schizotypy in a psychiatric population : an analysis using multidimensional Rasch models.

Schizophrenia Bulletin 26, 565–575.

Vollema MG, van den Bosch RJ (1995). The multidimensionality of schizotypy. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21, 19–31.

Vythilingam M, Chen J, Bremner JD, Mazure CM, Maciejwski PK, Nelson JC. Psychotic depression and mortality. Am J Psychiatry. 2003; 160: 574-576.

Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA. 1996; 276: 293-299.

Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Merikangas KR. Is delusional depression related to bipolar disorder? Am J Psychiatry. 1984; 141:892–893.

Wittchen H-U, Ho¨fler M, Lieb R, Spauwen J, van Os J (2004) Depressive und psychotische Symptome in der Bevo¨lkerung –Eine prospektiv-longitudinale Studie (EDSP) an 2.500 Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen. Paper presented at the DGPPN Congress, Berlin, 24–27 Nov 2004 (Abstract published in Nervenarzt 75: Suppl. 2:87)

Witte TK et al. Factors of suicide ideation and their relation to clinical and other indicators in older adults. J affect Disord, 2006, 94, 165-172.

Zanardi R, Franchini L, Gasperini ; et al. Double-blind controlled trial of sertraline vs paroxetine in the treatment of delusional depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1996; 153: 1631-1633.

42

Zanardi R, Franchini L, Gasperini ; et al. Faster onset of action of fluvoxamine in combination with pindolol in treatment of delusional depression: a controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998; 18: 441-446.

Zanardi R, Franchini L, Gasperini ; et al.Venlafaxine vs fluvoxamine in the treatment of delusional depression: a pilot double blind controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000; 61: 26-29.

43 Attached

44

Table 1. Frequency of endorsement of items comprising the psychotic dimension

Psychoticism dimension items Endorsement

95.you felt surrounded by hostility, as if everybody was against you 0.743

96.everyone was talking about you 0.702

94.others were causing all of your problems 0.610

83.very vulnerable. 0.568

97. heard voices 0.535

45

Table 2 Demographic characteristics in patients with high and low psychoticism dimension LP (N = 182) HP (N = 104) T-test / Chi-square test P Gender F (%) 157 (44.9) 94 (26.9) 1.16 0.28 Age (mean, sd) 29.6 (13.1) 24.6 (12.0) 3.14

Education level (mean, sd) 13.9 (27.7) 13,6 (3.3) 0.67 0.50

Working Status (%) Employed Home Maker Unemployed Other 153 (43.7) 22 (6.3) 23 (6.6) 27 (7.7) 76 (21.7) 8 (2.3) 10 (2.9) 31 (8.9) 10.07 0.01

Married or Living with Partner, N (%)

46

Table 3 Clinical correlates on psychoticism dimension LP (N = 182) HP (N = 104) t test / Chi-square test P

Age at onset of depression, mean (SD) 29.6 (13.1) 24.6 (12.0) 3.14 0.001

Duration of illness (years), mean (SD) 11.3 ( 12.0) 12,7 (13.4) -0.64 0.520

Recurrent depression, N (%) 74 (25.9) 122 (42.7) 0.521 0.470

History of suicide attempts, N (%) 20 (7.0) 19(6.7) 3.032 0.082

Family history, N (%) 100 (54.9) 61 (58.7) 0.37 0.543

HAM-D, mean (SD) 18.5 (3.5) 19.3 (4.3) -1.73 0.103

Q-LES-Q, mean (SD) 48.8 (9.1) 45.0 (9.8) 2.75 0.006

47

Table 4 a – Psychoticism dimension and MOODS-SR, controlling for HDRS-17 LP

(N = 182)

HP (N = 104)

F P (=value)

Mania/hypomania component factors

Psychomotor activation 4.36 (3.00) 6.96 (3.10) 1.87 0.173 Creativity 3.74 (2.74) 5.04 (2.98) 0.04 0.849 Mixed instability 1.46 (1.45) 2.09 (1.86) 0.00 0.946 Sociability/extraversion 2.20 (1.85) 2.50 (1.98) 0.04 0.832 Spirituality/mysticism 0.43 (0.87) 0.91 (1.20) 6.29 0.013 Mixed irritability 2.19 (1.46) 3.36 (1.60) 4.01 0.046 Inflated self-esteem 1.04 (1.26) 2.17 (1.67) 1.80 0.180 Euphoria 2.01 (1.56) 2.59 (1.70) 0.25 0.614 Wastefulness/Recklessness 1.44 (1,26) 1.77 (1.32) 0.85 0.358

Depressive component factors

Depressive mood 12.74 (5.26) 15.44 (4.39) 4.04 0.045

Suicidality 1.54 (1.71) 2.33 (1.71) 12.88 <0.001

Drug illness related depression

0.80 (1.12) 0.95 (1.28) 0.07 0.788

Psychomotor retardation 7.58 (4.28) 10.19 (3.33) 2.64 0.105

48

Table 4b – Psychoticism dimension and anxiety spectra, controlling for HDRS-17 LP (N=182) HP (N=104) T-test P(=value) TOT OBS 42,13 (23,19) 48,98 (26,30) 0.99 0,320 TOT SHY 41,02 (31,14) 77,55 (33,96) 4.36 0.038 TOT PAS 26,54 (16,64) 45,01 (19,78) 22.93 <0.001 PAS-SR Factors 1.Panic Symptoms 3,91 (3,86) 6,55 (4,74) 29.50 <0.001 2.Agoraphobia 1,64 (2,62) 3,66 (3,75) 4.82 0.029 3.Claustrophobia 0,83 (1,40) 1,71 (2,12) 11.25 0.001 4.Separation Anxiety 1,47 (2,06) 2,67 (2,77) 12.61 <0,001

5. Fear of Losing Control 1,97 (2,45) 3,25 (2,69) 15.42 <0,001

6. Drug sensitivity and phobia 1,21 (1,67) 2,48 (2,63) 5.18 0.024

7. Medical reassurance 0,28 (0,76) 0,56 (1,05) 3.43 0.065

8. Rescue object 0,32 (0,68) 0,63 (0,87) 2.38 0.124

9. Loss sensitivity 0,69 (0,79) 1,08 (0,84) 0.53 0.467

10.reassurance from family members

49

Figure 1 Association between psychoticism dimension and PAS-SR factors using stepwise linear regression analysis. Beta coefficients are presented

50

Figure 4. Association between psychoticism dimension and depressive factors of the MOODS-SR, using stepwise linear regression analysis. Beta coefficients are presented

51

Figure 5. Association between psychoticism dimension and depressive factors of the MOODS-SR, using stepwise linear regression analysis. Beta coefficients are presented

52

Table 6 Mood congruent/mood incongruent items on the psychoticism dimension

MOOD INCONGRUENT

95.you felt surrounded by hostility, as if everybody was against you 0.743

96.everyone was talking about you 0.702

94.others were causing all of your problems 0.610

97. heard voices 0.535

85. body transformed 0.386

98. heard voices clearly 0.299

MOOD CONGRUENT

83.very vulnerable. 0.568

93. you felt guilty or remorseful 0.523

82. preoccupied with yourself and your own problems, thoughts and

feelings 0.356

87. need to take refuge in religion or prayer 0.348

53

Figure 6. Correlations between mood congruent/mood incongruent on the psychoticism dimension and PAS-SR factors

P anic s ymptoms

A goraphobia

C laus trophobia

S eparation anx iety

F ear of los ing c ontrol Drug s ens itivity and phobia

Medic al reas s uranc e res c ue objec t los s s ens itivity reas s uranc e from family members

Mood c ongruent Mood inc ongruent

54

Figure 7. Correlations between mood congruent/mood incongruent on the psychoticism dimension and depressive factors of the MOODS-SR

Depres s ive mood

S uic idality

Drug illnes s related depres s ion P s yc homotor retardation

Neurovegetative s ymptoms

Mood c ongruent Mood inc ongruent

55

Figure 8. Correlations between mood congruent/mood incongruent on the psychoticism dimension and manic/hypomanic factors of the MOODS-SR

P s yc homotor ac tivation

C reativity

Mix ed ins tability

S oc iability/ex travers ion

S pirituality/mys tic is m Mix ed irritability

Inflated s elf-es teem E uphoria W as tefulnes s /R ec kles s nes s

Mood c ongruent Mood inc ongruent