ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Research

Policy

j o ur na l ho me p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / r e s p o l

Personal

relationships

and

innovation

diffusion

in

SME

networks:

A

content

analysis

approach

Federica

Ceci

a,∗,

Daniela

Iubatti

baDEA–UniversitàG.d’Annunzio,VialePindaro42,65127Pescara(PE),Italy

bIESEBusinessSchool–UniversityofNavarra,AvenidaPearson21,08034Barcelona,Spain

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received3November2010

Receivedinrevisedform3October2011 Accepted9October2011

Available online 8 November 2011 Keywords: Networks Personalrelationships Innovationdiffusion Contentanalysis

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Networkshavebeenhailedasathirdorganizationalform,betweenmarketsandhierarchies.Oneof themaincharacteristicsofnetworksisthecoexistenceofdifferentkindsofrelationships,personaland professionalamongthese.Thepresenceofmultipletypesofrelationshipsmodifiesinter-firmdynamics, creatingaspacewheretraditionalinnovationactivitiestakeplaceinanunusualway.Thepresentpaper investigatestheroleplayedbypersonalrelationshipswithinnetworks,addressingthefollowingresearch questions:howdodifferenttypesofrelationshipsexistinginanetworkofSMEsfavourthedevelopment ofeconomicactivities?Anddopersonalrelationshipsplayaroleinsupportinginnovativeactivities?To answerourresearchquestions,weanalyzedqualitativedatausingcontentanalysismethodology.Content analysisallowsresearcherstoobtainanobjective,systematic,andquantitativedescriptionofthemanifest contentofacommunication.Basedonthisanalysis,weconcludethatthecoexistenceofpersonaland professionalrelationshipsshapesauniquecontextthatalterstheusualdynamicsofinnovationdiffusion. © 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Anetworkhasbeendefinedasahybridcoordinationmechanism

ofeconomicactivitythatcombinestheadvantagesofboththe

tra-ditionalgovernancemechanismsofverticalintegrationandmarket

exchanges(Brassetal.,2004;Faemsetal.,2008;Grandori,1997;

Kogut,2000;Powell,1990).Duetoitsuniquepositioningbetween

marketsandhierarchies,an“apriori”definitionofits

characteris-ticsisnotpossible.However,thepastfewyearshavewitnesseda

flourishofempiricalstudies,aimingtounderstandhoweconomic

activitiesoccurinanetworkedstructure(Brassetal.,2004;Faems

etal.,2008;Grandori,1997;Kogut,2000;Powell,1990;Tortoriello andKrackhardt,2010).Morespecifically,innovationscholarshave

devotedtheirattentiontothenetworkdynamicsthatleadtothe

generationanddiffusionofinnovationwithinnetworks(Giuliani

andBell,2007;Granovetter,1985;Gulati,1998;Iubattietal.,2010; Kogut,2000;LorenzoniandLipparini,1999).Networkand

inno-vationliteraturehasshownthatfirmsbelongingtonetworksare

moreinnovativethanisolatedfirms(Ahuja,2000;Baptista,2000;

BaptistaandSwann,1998;Brassetal.,2004;PodolnyandStuart, 1995;Powelletal.,1996),identifyingaseriesoffactorsthatresult

inthesepositiveassociations:higherflexibility,greaterabilityto

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddresses:[email protected](F.Ceci),[email protected](D.Iubatti).

change,morefluidknowledgeflowsandthepresenceofalarge

varietyofrelationshipsamongmembers(Cooke,2001;Dahland

Pedersen,2004;GiulianiandBell,2005;InkpenandTsang,2005; PadgettandPowell,2011).

Inthepresentwork,webuilduponthelatterstreamofresearch:

differenttypesofrelationshipscoexistwithinnetworksandmodify

inter-firm dynamics,creatingaspacewhere traditional

innova-tionactivitiestakeplaceinanunusualway.Multiplerelationships

leadtotheexistenceofmultidimensionallinks.Seminal

contribu-tionshavehighlightedthatthedynamicsofeconomicactivitiesare

largelyinfluencedbythemultidimensionalcharacteristicsof

net-works(Brassetal.,2004;Faemsetal.,2008).Recently,Padgettand

Powell(2011)focusedtheirattentiononhowmultidimensional

links,inparticularpersonalandprofessionallinks,contributein

dif-ferentwaystothesocialandeconomicdevelopmentofnetworks.

Focusingonthepersonalaspectsofrelationships,wealreadyknow

thateconomicdecisionsarelargelyinfluencedbythepresenceof

trust betweenplayers(Granovetter,1985;Gulati,1995;Lawson

etal.,2009;Uzzi,1997).However,westillknowverylittleabout

theimpactthatmultipledomainshaveoninnovationdynamics.

The present article investigates the role played by personal

inter-firmrelationshipswithinnetworks,addressingthefollowing

researchquestions:howdodifferenttypesofrelationshipsexisting

inanetworkofSMEsfavourthedevelopmentofeconomic

activi-ties?Dopersonalrelationshipsplayaroleinsupportinginnovative

activities?

0048-7333/$–seefrontmatter © 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.10.003

We address these research questions through an empirical

analysisof aconsortiumofSMEslocatedin Abruzzo(Italy)and

composedof15SMEsoperatingintheautomotiveindustry.The

consortiumis characterized by a large variety of relationships,

horizontalaswellasvertical,formalandinformal,personaland

professional.Within this consortium,personal and professional

relationshipsarecloselylinked.Thiscontextrepresentsaunique

scenariowithinwhichweanalyzetherolethatpersonaland

profes-sionalrelationshipsplayinpromotingthediffusionofinnovation.

Weuse content analysis methodology to examine the data in

ordertoensuretheobjective,systematicandquantitative

descrip-tionofthecommunicationcontents(Berelson,1952;Krippendorff,

2003).Contentanalysisisaresearchmethod,initiallydiffusedin

socialstudies,thatallowsmeasuringthecontentof

communica-tiononthebasisoftextualanalysis(interviews,politicalspeeches,

laws,booksandnewspapers).Toreachhighlevelsofobjectivity

andexternalvalidity,theanalysisisimplementedbyfollowinga

codingprocedure(Duriauetal.,2007;Inschetal.,1997;Morris,

1994;ZaheerandSoda,2009).Althoughtheuseofcontent

anal-ysisinmanagerialstudiesisincreasing,toourknowledgethisis

thefirststudythatusescontentanalysisasaprimarymethod.We

usecontentanalysistoanalyzeinterviewsandobtainquantitative

informationformqualitativedata.Indoingso,westrictlyfollowed

theguidelinesprovidedbyKrippendorff(2003).

Our results describe how the diffusion of innovation takes

place and what the dynamics between activities and

per-sonal/professionalinter-firmrelationshipsare.Thecontributions

ofthepresentworkarethreefold:(i)thediffusionofinnovation

isenabledbypersonalrelationships:thepresenceoftrust,shared

valuesandmutualobjectivesfacilitatesthecommencementofa

difficultandriskypath,suchasthatcharacterizingtheadoption

ofinnovation;(ii)strategicandinnovativeactivitiestakeplacein

differentnetworksofrelationships:thelocusofinnovationisnot

thelocusofstrategy;(iii)innovativeactivitiesarewidelydiffused

withinnetworks,exploitinga largevarietyof relationshipsand

involvingmultiplenetworkdimensions.Onafinalnote,webelieve

thatthis paperalsomakesa significantcontributioninthefield

ofmanagerialresearch,adoptinganovelmethodologicalapproach

intheanalysisoftextinterviews.Theremainderofthearticleis

organizedasfollows.InSection2,wereviewcontributions

inves-tigating therole of network features and personal/professional

relationshipsinthediffusionofinnovation,Section2.1explores

thecharacteristicsofnetworksandSection2.2highlightsthe

dis-tinctivefeaturesofpersonalrelationshipsinnetworks.Section3

developstheanalyticalmodelthatguidestheanalysisofthe

empir-icalevidences,Section4describestheempiricalcontextinwhich

theresearchisgrounded,andSection5explainsthemethodology

usedinthisstudy.Thelasttwosectionsdiscussourresults,draw

conclusionsanddescribetheimplicationsofthepresentresearch

forpractitionersandscholars.

2. Literaturereviewandmodeldevelopment

2.1. Networksandthediffusionofinnovation

Sincethebeginningofthe1990s,organizationalscholarshave

enrichedthetraditionaldichotomybetweenverticalintegration

andmarketexchangesbyidentifyingtheexistenceofnetworks

asathirdorganizationalform.Networks,definedbyPowelland

Smith-Doerr(1994)as“asetofnodeslinkedbyasetofrelations,

suchasfriendship,kinship,political,etc.”(PowellandSmith-Doerr,

1994:p.3),areseenasenablingthecombiningoftheadvantages

ofthetwo long-establishedtraditional governancemechanisms

(Brassetal.,2004;Coase,1937;Powell,1990;Williamson,1975, 1979).

Oneof thefirstconceptualization ofnetworksis ascribedto

Marshall(1890)whoidentifiedindustrialdistrictsasanexampleof

networksoffirmsthatcollaboratetoproducethesameoutputand

operateinarestrictedarea(Becattini,1986,1990;Marshall,1890).

Asheim(2000)emphasizedthatthedistinctivenessofindustrial

districtis thecombination of functional and territorial

integra-tion. Industrial districtsreflect thesocio-culturaland economic

influenceofthecontextsinwhichtheydevelop(Lundvall,1992).

Furthermore,suchdimensionsfollowterritorialdynamicsthatlead

tothegenerationofacomplexandgeographicallybounded

sys-temsofcomplementaryspecializedorganizations(AminandThrift,

1994;Asheim,2000;Storper,1997).Insuchsystems,innovation

cannotbeseenasalinearprocessbutitmustbeanalyzedasasocial,

non-linearandinteractiveprocess(Lundvall,1992),inwhich

terri-torialandsocio-culturalvariablesplaysignificantrolesinshaping

innovativeoutputsovertime (Asheim,2000;Whittingtonetal.,

2009).Contributionsinthefieldofindustrialdistrictsarecrucialto

understandthespecificitiesofinnovationdynamicstakingplacein

acontextofsmallandmediumfirms(SMEs)(Becattini,1986,1990;

Marshall,1890;Storper,1997).Firmsorganizedasanindustrial

districtbenefitfromwhatMarshall(1890)called“industrial

atmo-sphere”,whichisconstitutedbyasetofdistinctiveresourcesand

relationships(personalaswellasprofessional)betweenmembers

ofindustrialdistricts,facilitatingtheacquisitionoftacitknowledge

andothertypesofinformalskills(Asheim,2000;Bellandi,1989).

The“industrialatmosphere”isthusaparticularenvironmentthat

enablesthegeneration ofinnovation. Insuchcontexts,

innova-tionisfacilitatedbynon-marketandnon-economicfactors,suchas

trust,socialcapital(Putnam,1993)andbytheexistenceofeffective

informationnetworks(Asheim,2000;Garofoli,1991).Thisallowsa

broaderandfastercirculationofinformationaboutmarkets,

alter-nativeproductiontechniques,newrawmaterials,andcomponents.

Moreover,territorialclosenessfacilitatestheinter-organizational

transferoftacitknowledgeaboutlabourprocessandproduction

techniques.Theinteractionofthoseelementsfacilitatesthe

diffu-sionofinnovationsinthewholedistrict(Asheim,2000;Becattini,

1990,1991).

OtherstudiespointedoutthatSMEscollaborateinordertohave

somecontrolover theexternalenvironment, leveragingon

fre-quentandfacilitatedknowledgeexchanges(StorperandWalker,

1989).Inparticularcontexts,thecreationofa networkofSMEs

ispromotedbyalargefirmthatidentifiesinapotentialnetwork,

suchasanetworkofsub-contractorsorsuppliers,awaytocompete

inchangingglobalmarkets(Smith-RingandVanDeVen,1992).

Scholarshavelargelydevotedtheirattentiontoincreasingtheir

understandingofnetworkdynamics,studyingfactorsthatenable

thecreationofnetworks,theirinnercharacteristics,andthe

dis-tinctivefeaturesthatdeterminetheiruniquewaysofknowledge

sharingand transfer (Deroian, 2002; Granovetter,1985; Gulati,

1998;Knoke,1990;Kogut,2000;Smith-DoerrandPowell,2004).

Numerouscontributions,alsofromthesociologyfield,attest

thatfirmsbelongingtonetworksaremoreinnovativethanisolated

firms(Ahuja,2000;Baptista,2000;BaptistaandSwann,1998;Brass

etal.,2004;PodolnyandStuart,1995;Powelletal.,1996).

Schol-arshaveidentifiedaseriesoffactorsthatresultinsuchapositive

association.Morespecifically,giventheflexibilityprovidedbythe

smallerorganizational unitswithinthenetwork itself,networks

areabletorapidlyevolveandadapt tochanging environments,

adoptingthemostappropriatestructure(Cooke,2001;Cookeand

Wills,1999;Dosi,1988).Moreover,smallerunitsconstitutinga

net-workrelatetooneanotherandenablethespreadofknowledge.

Withinnetworks,flowsofknowledgearefacilitatedand,therefore,

thelikelihoodof adoptionand diffusionof innovationincreases

(Dahland Pedersen,2004;Sorensonetal.,2006).Thisis dueto

thepresenceofasetofrelationshipsestablishedby

knowledgesharingamongfirms(GiulianiandBell,2007;Keeble andWilkinson,1999).Thelearningprocessesoffirmsareexpedited

iffirmsareexposedtoexternalsourcesofknowledgethatenhance

knowledgeexchanges(Burt,1992;InkpenandTsang,2005;Knoke,

1990).

Finally,asignificantbodyofliteraturehasexploredhow the

structureofnetworks,thepresenceofstrongandweakties,

struc-turalholes,andthepositionoccupiedbyafirm inthenetwork,

caninfluenceinnovativeoutputs(Burt,1992;Granovetter,1983;

InkpenandTsang,2005;Krackhardt,1992;Powelletal.,1996).The

strengthofatieisdefinedas“acombinationoftheamountoftime,

theemotional intensity,[...] and thereciprocal serviceswhich

characterizethetie”(Granovetter,1973:p.1361).Therefore,strong

tiesareassociatedwithamutualalignmentinwhichknowledge

flowsinbothdirections(Hansen,1999;MarsdenandCampbell,

1984) while in weak ties “actors are less likely to be socially

involvedwithoneanother”(Granovetter,1983:p.201).Inorder

to better understand the characteristics of inter-organizational

networks,Burt(1992)introducedthekeyconceptof“structural

holes”.Structuralholesrepresentbridgesbetweenotherwise

dis-connected networks. They play an essential role in increasing

knowledgeexchangesandfirminnovationeffectivenesssincetheir

presenceenhancesdiversityandknowledgevariationwithinand

betweennetworks(Burt,1992;Capaldo,2007).

Thestructureofthenetworkinfluencesandshapesthetypes

ofrelationships(strongorweakties)betweenfirms(Inkpenand

Tsang, 2005; Powellet al., 1996).For example,in

manufactur-ing networks, we can observe the presence of (i) strong ties

within a small core and (ii) weak ties in the periphery of the

samenetwork(Burt,1982;Gomes-Casseres,2006;Tortorielloand

Krackhardt,2010).Often,abiggerorganizationrepresentsthecore

ofanetworkofsmallerfirmslocatedintheperiphery(Capaldo,

2007;Krackhardt,1992).In sucha context,in therelationships

betweencoreandperiphery(verticalnetworks)theactorstendto

developstrongties,whereasin horizontalandcompetitive

net-works (within the periphery), firmsrely on structural holes in

ordertoexchangeknowledgeandincreasetheirinnovation

per-formances(Capaldo,2007;Park,1996).

Thecontributionsdiscussedaboveexploredthetypesof

net-works and their characteristics in terms of network structure,

knowledgeflowsandinnovationswithinthem.Literaturesuggests

thatdifferenttypesofrelationshipsaregeneratedaccordingtothe

characteristicsofthenetwork(Capaldo,2007;InkpenandTsang,

2005;Park,1996;Powelletal.,1996),whichinturnhavean

impor-tantroleininfluencinginnovationadoptionanddiffusion(Ahuja,

2000;AroraandGambardella,1990;Capaldo,2007).Hence,the

characteristicsofrelationshipsinnetworks,asdiscussedbelow,are

essentialinthedeploymentofeconomicactivities.

2.2. Personalrelationshipsinnetworks

Networksarecomposedofmultidimensionallinks(Brassetal.,

2004; Faems et al., 2008; Padgett and Powell, 2011). Padgett andPowell(2011)emphasizethatthosemultidimensionallinks

contributenotonly tothesocial and economicdevelopmentof

networks,butalsotoknowledgesharing,tothedevelopmentof

newrelationshipsamongactorsandtothegenerationofnew

sub-networks.Inparticular,socialandpersonalrelationshipsincrease

informationflowswithinnetworks:whenpersonalrelationships

exist,actorstendtoenhanceknowledgesharingbecauseof the

existenceoftrust. Lorenzen(2001)definestrust as“acognitive

coordinationmechanism”(Lorenzen,2001:p.16),distinguishing

between(i)dyadicandnetworkedtrust,characterizedbymutual

interestinexclusivenetworksoffirms,and(ii)socialtrust,which

isdevelopedthroughlocalinformationspreadingandsocial

learn-ing processes in industrial clusters. The former is particularly

importantinsmallnetworksoffirms,whilethelatter,enablinggoal

alignment, representsaneffectivecoordination mechanism and

preventsopportunisticbehaviours(Lorenzen,2001).Inparticular,

socialtrustreliesmainlyonpersonalrelationships(Granovetter,

1985;Lorenzen,2001).Personalrelationships,enablingpartnersto

trusteachother’sbehaviours,fosterknowledgeexchangesthatare

essentialforthedevelopmentofnetworks(Gulati,1998;Mellewigt

etal.,2007).Clearly,professionalrelationshipsarebasedontrust

and aredrivenbythefirm’sprofessionalreputationinits

busi-nessactivities,whilepersonalrelationshipstriggerthecouplingof

trustwiththesharingofcommonvalues(Lorenzen,2001).Hence,

personalandprofessionalrelationshipsaresupportedbydifferent

typesoftrust,namelyemotiveandcapacitytrust(Ettlinger,2003),

althoughtheyinteractwitheachother.Emotivetrustdevelopswith

positivepersonalfeelingsaboutothers,whilecapacitytrustisbased

onthecompetencesofothersinprofessionalsettings.Inmostcases,

capacitytrustisderivedfromemotivetrustthatisdevelopedina

differentcontext(Ettlinger,2003).Aconsequenceoftheexistence

ofmultidimensionallinksinnetworksisthatactors,onthebasisof

emotivetrustpreviouslydeveloped,areinclinedtocooperateand

exchangeknowledgewitheachother(Gulati,1998;Padgettand

Powell,2011).

An important contributionto ourunderstanding of the role

of personal relationships in economic systems derives from

Granovetter(1985,1992),whoarguedthatthereisa“widespread

preferencefortransactingwithindividualsofknownreputation”

(Granovetter,1985:p.490).Thisbehaviourleadstotheconcept

ofembeddedness,which“stresses[...]theroleofconcrete

per-sonal relations and structures(or“networks”) of suchrelations

in generatingtrustand discouragingmalfeasance”(Granovetter,

1985:p.490).Economicactionsandoutcomesareaffectedbya

setofsocialrelationshipsandtheoverallstructureofnetworksin

whichtheyareembedded(Granovetter,1985,1992).Contributions

onthistopicexplainthatinnetworkscharacterizedbyembedded

relationships,firmsaremotivatedtopursuegoalsthatcouldlead

toanabsenceofimmediateeconomicrevenueandgrowthinorder

toattainthestrengtheningofthenetwork(Powell,1990;Provan

etal.,2007;Smitka,1991;Uzzi,1996,1997).

Networkedfirmsintensifytheembeddednessphenomenaby

developingdifferentsetsofpersonalrelationships,whicharelikely

tobesupportedbyinformalcontactswitheachother(Brownand

Duguid,2001).Personalrelationships,whensupportedby

infor-malcontacts,enhanceembeddedness,whichinturnallowsfirms

to obtainsignificantoutcomes, suchasknowledge sharing and

thediffusionofinnovation.In thiscase,trustworks asa

gover-nancemechanismofembeddedrelationships(Granovetter,1985;

Lawsonetal.,2009).Therefore,activitiesbasedonclosepersonal

relationshipsarefacilitatedthroughthedevelopmentofasortof

“businessfriendship”,whichmotivatesfirmstogobeyondtheir

for-malcontractswhendoingbusinesstogether(Gilsingetal.,2008;

Granovetter,1985;Larson,1992;Uzzi,1997).

3. Analyticalmodeldevelopment

Studies onnetworks demonstratethat oneof theiressential

characteristics is identifiedin thetypes of relationshipsamong

allthemembersthattriggerknowledgeexchanges.Moreover,the

differenttypesofrelationshipsinfluenceknowledgesharingin

var-iousways(BrownandDuguid,2001;PadgettandPowell,2011).

Startingfromthecurrentstateoftheart,wewantedtogoastep

furtherinthenetworkfieldandexplorehowpersonalrelationships

amongmembersenablethediffusionandadoptionofinnovationas

essentialkeyeffectsofknowledgeexchanges(BreschiandLissoni,

ourresearch,weanalyzedempiricaldatathroughthelensofan

analyticalmodelthatwewilldescribeherewithfollowing.

3.1. Personalandprofessionalrelationships

To investigate the role of relationships, we classified the

relationshipsamongnetworkedmembersintopersonaland

pro-fessional relationships. According to Lincoln (1990), personal

relationshipsarethosethatproduce“relationsoftrust,obligation,

andcustom”(Lincoln,1990:p.281)amongformallyindependent

nodes,whileprofessionalrelationshipsareidentifiedintermsof

thevarious connections that bring peopletogether todo

busi-nessinordertopursueeconomicgoals.Personalrelationshipsare

basedontrustandmutualobligations,relyonpersonal

embedded-nessamongactorsandgobeyondimmediateeconomicgain(Dore,

1987;Larson,1992).

Inourstudy,wecategorizepersonalrelationshipsas:(i)familiar

andfriendship,(ii)geographicaland(iii)othertrust-based

relation-ships.Familyandfriendshipsarecharacterizedbypre-developed

andcloserelationshipsamongindividualsthatoperateinthefirms

ofanetwork(CrossandBorgatti,2000;PadgettandPowell,2011;

Powell,1990).Cooley(1909)definedafamilyasaprimarygroup

characterizedby “intimateface-to-face association and

cooper-ation”(Burt, 1980; Cooley, 1909: p. 23), supported by current

interactionsthatshapethestructureofthenetworks(Smithand

Stevens,1999). Furthermore,friendship relationshipspositively

affect“theprocessofcommunicationinproducinguniformityof

attitudes,opinionsandbehaviour”(Festingeretal.,1950:p.175),

thusincreasingknowledgeexchangesbetweenindividualssince

theyare alsousedinseekingadviceand collectinginformation

(AdlerandKwon,2002;Burt,1987).

Geographicalproximityisanenablerofpersonalrelationships

sincethereciprocalclosenessofnetworkedmembers,workingin

thesamegeographicalarea,allowsthedevelopmentof

relation-shipsthat are not solely related tothe professional dimension

(Lissoni, 2001; Rallet and Torre, 1999). However, geographical

proximityisnottheonlyvariablethatenablesthedevelopment

ofpersonalrelationships;previousworkidentifiedothertypesof

proximity(cognitive andsocial proximity amongthose) as

ele-mentsfacilitatingsuchrelationships(Boshma,2005).Infact,the

development of personal relationships is enabled not only by

spatialcloseness,butalsoby(i)knowledgeproximity,which

pro-videsopportunitiesandsetsconstraintsforfurtherimprovement

(Boshma,2004,2005),and(ii)socially embeddedrelationships,

whichinvolvetrustandtacitknowledgeexchange(Boshma,2005;

Maskell and Malmberg, 1999). Hence, geographical proximity

canbe complementary toother types of proximity in building

andstrengtheningpersonalrelationships(AudretschandStephan,

1996;Boschma,2005;Harrison,1992;Hausmann,1996):closely

locatedfirmshavemorepossibilitiestodevelopface-to-face

inter-actions and can build up trust and shared recognized shared

values more easily than long-distance related firms (Harrison,

1992).Therefore,geographicalproximity,constitutesanimportant

variableforthedevelopmentofpersonalrelationships,although

excessiveproximity,beit geographical,cognitiveorsocial,may

generatelock-inphenomenainembeddedrelationships,

constrain-ingfirmcompetitiveness(Boshma,2005,2004;Morgan,2004).

Finally, we define personal relationships according to the

existenceofpersonaltrustandobligation.Amongthe“other

trust-based relationships” we identified political relationships as an

important category. Political relationshipsare trust-based links

thatgobeyondformalandcodifiedrulesandenhancethespeed

andqualityofknowledgesharingamongmembersofanetwork

(Edquist,1997;Gulati,1998).Moreover,thepresenceofstable

rela-tionshipswithlocalpublicauthorities constitutes animportant

frameworkforanyactivity,economicaswellassocial:personal

contacts with localinstitution members favour the creation of

newnetworkdimensions(EdquistandJohnson,1997;Padgettand

Powell,2011).

Professional relationships rely on specific business-related

knowledgeexchanges.ReferringtoLincoln’s(1990)definition,

pro-fessional relationshipsaremainly fosteredbythe firm’saimto

managebusinessactivities.Numerousauthorshavefocusedtheir

attentiononthemanagementofbusinessactivitiesthroughwhat

theycall‘businessrelationships’(Achroletal.,1983;Baker,1990;

Holm et al., 1999),defining them as “relationships where two

partnerscoordinateanumberofexchangeandproduction

activ-ities”(Holmetal.,1999:p.469)toincreasetheirjointeconomic

performance.Professionalinteractionsamongfirmsgenerate

inter-dependentcapabilities and routines withregard toproduction,

logistics and quality management, and facilitate the

coordina-tionandallocationofresourcestoimprovejointproductivity(e.g.

Andersonetal.,1994;CunninghamandHomse,1986;Johansonand Vahlne,2003;JohnstonandLawrence,1998;Petersenetal.,2003).

Theserelationshipsoccurwithclients,suppliers,potential

part-nersand competitors. Accordingly,professionalrelationshipsin

ourmodelareclassifiedasfollows:(i)association-related

relation-ships,suchasrelationshipswithothermembersofanyindustrial

association,(ii)relationshipswithclients,(iii)relationshipswith

competitors,and(iv)relationshipswithsuppliers.

3.2. Economicactivities

In our conceptualization of networks, relationships among

membersareseenasavehicletofacilitatethedeploymentof

eco-nomicactivities.Wedivideeconomicactivitiesintothreetypes,

namely:(i)innovative,(ii)strategicand(iii)operationalactivities.

Todefineinnovativeactivitieswerefertotheconceptof

innova-tion.Scholarshavelargelydebatedthisconcept,onceconfinedto

meretechnologicalchanges.Overthelastdecades,thisconcepthas

beenwidelyenlargedtoincludenewperspectives.Infact,

inno-vation hasbeendefined as“new combinations” ofpre-existent

resourcesandknowledgeaswellasneworganizationaland

insti-tutionalstructuresthatenabletheeconomicdevelopmentoffirms

(EdquistandJohnson,1997;Lundvall,1993;MalerbaandOrsenigo,

2000).Inourmodel,innovativeactivitiesareoperationalizedinto

threecategories:(i)productandprocessinnovations,(ii)

organiza-tionalinnovationsand(iii)innovationsrelatedtotheintroduction

ofITs. Wepaidparticular attentiontotheuseofITs,conceived

asorganizationaltoolsthatenableeconomicdevelopment,since

theiradoptionisakeyissueforSMEs.Duetothedelayintheir

adoption,theuseofthesetechnologiesisconsideredanimportant

innovativeprocessforSMEs(Bayo-MorionesandLera-Lopez,2007;

Pantjadarma,2004;Passiante,2010).

Thesecondtypeof activitiesrelatestofirm strategy.Rumelt

(1984)defined strategy formulation as“theconstant searchfor

waysinwhichthefirm’suniqueresourcescanberedeployedin

changingcircumstances”(Rumelt,1984:p.569).Abetteruseof

resourcesandadaptationtochangingenvironmentsconstitutethe

main challenges in achieving a competitiveadvantage, both in

termsofgrowthandsustainedprofitability(CastaniasandHelfat,

1991).Fromthis perspective,networkedfirmsareengagedina

widearrayofstrategicactivities.Insomespecificnetworks,the

jointdevelopmentofstrategicactivitiescanbeconsideredasthe

maindriveroftheirgrowth(DittrichandDuysters,2007;Grandori

andSoda,1995;Walkeretal.,1997).Thestrategicdimensionof

firmactivitiesmustbeevaluatedbyconsideringthe

environmen-tal context where those activities takeplace. Focusing on SME

networks, we identified three subcategories:(i) growthrelated

activities,(ii)marketingactivitiesand(iii)activitiesthatsupport

thedevelopmentofasharedculture.Growth-relatedand

purposeofhelpingfirmsinthenetworkgainacompetitive advan-tage(SwaminathanandMoorman,2009).Infact,belongingtoa

network enhances firm activities as internal relationships

con-tributesignificantlytotheirgrowthandeconomicsuccess.Their

smallsizedoesnotallowthemtofacecompetitiveenvironments.

Conversely,actingasasingleeconomicactor,networkedfirmsgain

accesstobothspecificcontextsandcompetitiveadvantage(Doz,

1987;Larson,1992;Walker,1988).Thedevelopmentofashared

culture is a strategic network asset. Mutual commitment and

reciprocaltrustenforcethefirm’sinvolvementinnetworkgoals,

supportingothermembers’performancesandgrowth.Therefore,

asharedcultureisanessentialprerequisitefortheachievementof

anygoal(PfefferandSalancik,1978;Thompson,1967).

Finally,weincludefirmoperativeactivitiesinthemodel.

Opera-tiveactivitiesaredefinedasongoingactivitiessuchas(i)budgeting

andplanning,(ii)designandengineering,(iii)purchasing,and(iv)

sales(Larson,1992).Day-to-dayexchangesaremostlysupported

byrelationshipsthatdonotrequirestrongmutualcommitment;

thesetypesof iterativerelationshipsrender operative activities

successful, allowing their incremental development over time

(Larson,1992).

3.3. Modeldevelopment

The contributions of scholars exploring the importance of

relationshipswithinnetworkshighlightthedifferentimpactsof

personal and professional relationships on economic activities.

However,westillknowverylittleabouthowpersonal

relation-shipssupporttheseactivities.Infact,nodifferenceshavesofarbeen

identifiedinnetworkandinnovationliteratureonwhattypesof

activitiesarebettersupportedbypersonalrelationships.Withthe

aimofunderstandingnetworkdynamicsfurther,wetestthe

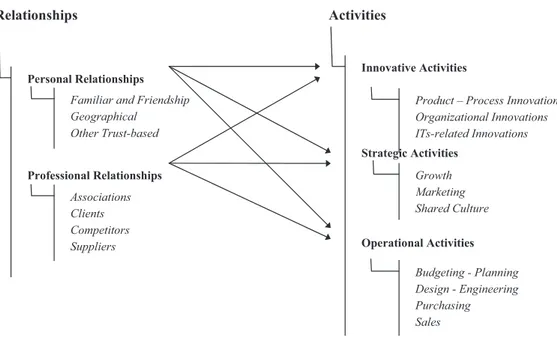

ana-lyticalmodelreportedinFig.1.Onthelefthandside,personaland

professionalrelationshipsareshownandlinkedtothethreetypes

ofactivitiesdiscussedaboveandpositionedontherighthandside

ofthegraph.Inparticular,throughtheanalysisofempiricaldata,

wewantedtoexplorethestrengthofthesupportfosteredbythe

differenttypesofrelationshipsinassociationwiththethreetypes

ofactivities.

4. Theempiricalcontext:CISIconsortium

The empirical context of this study is the CISI consortium

(ConsorzioItalianoSubfornituraImpresa),constitutedby15SMEs

operating in the automotive industry. The CISI consortium is

locatedinValdiSangro(Abruzzo,Italy),animportantindustrial

areaspecialized inthemechanicalsector.It comprisesthe

sub-sidiariesofamajorglobalautomotiveplayer,HondaItalia,which

hasaproductionplantlocatedinthesamearea.Inthelate1970s,

themanagementofHondaItaliaencouragedthecreationof

cap-tivesuppliersinordertoimplementjust-in-timeprocedureswith

localfirmsthatexperiencedsignificantgrowth.13ofthese

suppli-ersdecidedtogrouptogethertocreateaconsortiumofSMEs.The

CISIconsortiumwasfoundedin1992,comprising15membersin

2007withover800employeesintotalandannualrevenuesof100

millionEuros.14outof15membersarelocatedin8townsinthe

sameadministrativearea(seeTable1forfurtherdetails)andare

(onaverage)20kmfromthemainclient(HondaItalia).Thefirms

arepositionedinanareaofover1.000km2.Onlyonefirmisfamily

owned(generalpartnership),2firmsarepubliclimitedcompanies

andtheremaining12areprivatelimitedcompanies.Theyarenot

partofanynationalormultinationalgroup.

Althoughthefirmswerebornas captivesuppliersof Honda

Italia,CISImembershaveexpandedtheirclientbasetoincludethe

followingmultinationalcompanies:ABB(Sweden),Aprilia(Italy),

BMW(Germany),BRP(Canada),Ducati(Italy),Fiat(Italy),

Honey-well(USA),KTM(Austria),MotoGuzzi(Italy),Piaggio(Italy),Rotax

(Austria), Trigano (Italy), Triumph (United Kingdom), Yamaha

(Japan). Inaddition,the supplierbaseof theCISIconsortiumis

international:componentsand rawmaterialsareboughtin

dif-ferent parts of theworld such asChina and the Far East(raw

materialandsmallcomponents),inEurope(componentsand

semi-finishedproducts)andinJapan(originalcomponentsfromHonda

Trading).

Theaimoftheconsortiumistoovercomethesizelimitationsof

individualmembers,leveragingontheirsharedvisionofbusiness

thatisbasedonHonda’sphilosophy.Theconsortiumdeveloped

commonmarketingactivitiessuchasparticipationinexposand

specializedevents—activitiesthatcouldnothavebeenundertaken

bythefirmsindividually.TheCISIconsortiumcomprisesalarge

varietyofrelationships,bothhorizontalandvertical,aswellas

for-malandinformal.Moreover,friendshipandbusinessrelationships

arecloselylinkedwithinCISI.Inthiscontext,theanalysisofthe

rolethatpersonalandprofessionalrelationshipsplayinenabling

thediffusion ofinnovation,suchas theadoptionof newITs, is

particularlyinteresting.

Thepresenceofadominantleader,generallyalargefirm,

influ-encing the creationand direction of supplier networks,is well

knowninmanagementliterature.Toyotaisakeyexampleofthe

Japanesephilosophy:itpromotesthegenerationofanetworkof

suppliersthroughthedevelopmentofcommonroutinesand

capa-bilities,playingthecentralroleof“convenor”oftheentirenetwork

(DyerandSingh,1998;Gray,1989).Inourempiricalcontext,Honda

Italiaimplementedthesamecommongovernancemechanism,but

animportantdifferencemustbehighlighted.Toyotaisthe“ego”

ofthewholenetwork(EverettandBorgatti,2005),fostering

com-municationamongsuppliersandsettingtherulesofknowledge

exchangeprocesses,whereasHondaItaliaisthepromoterofthe

CISIConsortium,leavingitsmembersfreetointeractanddevelop

theirownroutinesindependently.HondaItaliaisCISIsmainclient,

whichinturnhasdevelopedautonomouslyovertime.

5. Method

5.1. Methodologicalapproachtothenetworkanalysis

Galaskiewicz(2007)observedthebeginningofthediffusionof

networkanalysisintheUSAinthe1970s,whenitgrewin

pop-ularityasadirectreactionagainstsurveyresearchapproachesto

studyinghumanbehaviour.Networktheorywasattractivebecause

itofferedarigorous,quantitativemethodforstudyingindividuals

andorganizationsinrelationshipswitheachother(Galaskiewicz,

2007;Granovetter,1985).Provanetal.(2007)undertooka

com-pletereviewofstudiesoninter-organizationalnetworks,analysing

26 empirical studiespublishedin academicjournalsfrom1985

to 2005.Departing fromthestudies identified by Provanet al.

(2007),weexaminedthemethodusedtoobtainageneraloverview

of the most-used methodological approaches. Social network

analysis(SNA)appearstobethepreferredmethodtoanalyze

net-works(BorgattiandFoster,2003;Burt,1997;Krackhardt,1987;

Wasserman,1994)butothermethodologiesarealsoconsideredin

thescientificcommunity.

SNA was described by Scott (1988) as an instrument that

“depictsagents–individualorcollective–asembeddedinwebs

ofconnections,andthetaskofthesociologististodescribeand

explainthepatternsexhibitedintheconnections”(Scott,1988:p.

112).Withthehelpofdedicatedsoftware(Borgattietal.,2002),SNA

mapsandmeasuresformalandinformalrelationshipsto

under-standwhatfacilitatesorimpedestheknowledgeflowsthatbind

Personal Relationships

Professional Relationships

Familiar and Friendship Geographical

Other Trust-based Associations Clients Competitors Suppliers

Relationships

Innovative Activities

Strategic Activities

Operational Activities

Product – Process Innovations Organizational Innovations ITs-related Innovations

Budgeting - Planning Design - Engineering Purchasing Sales Growth Marketing Shared Culture

Activitie

s

Fig.1.Analyticalmodel.

informationandknowledgewithwhom,bywhatcommunication

media.

Asanticipatedabove,qualitativeapproachesareoftenused.In

particular,casestudymethodologyisappropriateforexplorative

analysisbecauseitallowsidentifyingandunderstandingthe

differ-entdimensionsthatcharacterizeaphenomenon(Eisenhardt,1989;

Leonard-Barton,1990;VanMaanen,1998;Yin,1994).Inthecaseof

networks,thisapproachispreferredifthereisnopriorresearch

thatallowsconductingmorebroad-baseddatacollectionand

anal-ysis(Bazzolietal.,1998)oriftheboundariesbetweenthecontext

andthephenomenonareblurred(VanRaakandPaulus,2001;Yin,

1994).Theuseofcasestudiesisalsoappropriateifresearchersare

involvedin datacollectionasparticipantobservers (Knight and

Pye,2005).Furthermore,somestudiesusecomputer-aided

pro-grams(e.g.NUD.IST)toanalyzedatacollectedthroughinterviews

anddocumentaldata(AraujoandBrito,1997).

In thepresent work,we usethe contentanalysis technique

toanalyzeourdata,constitutedbythetranscriptsofopen-ended

interviews. Content analysis is a “research technique for the

objective,systematic, and quantitativedescriptionof the

mani-festcontent of a communication”(Berelson, 1952: p. 18).This

methodwasdevelopedinsocialstudiesandinvestigatesthe

con-tent of communications. The initial applications were political

speeches, laws, books and newspapers. The advantages of this

research methodare its high levelsof objectivity and external

validity.Becauseofthediffusionofad-hocsoftware,thismethod

demonstrateditspotentialandhasincreasinglybeenusedsince

the1980s(Duriauetal.,2007;Insch etal.,1997;Morris, 1994;

ZaheerandSoda,2009).Throughtheuseofcontentanalysis,for

example,Gebaueretal.(2008)identifiedthefactorsthatusersfind

importantinmobiledevices;theresultsfromthecontentanalysis

werethenanalyzedwiththeuseofstructureequationmodelling.

ArecentstudybySonparandGolden-Biddle(2008)enhancedthe

valueofcontentanalysisasaninstrumentthatfacilitatestheory

elaboration.

5.2. Datacollectionandquestionnaireadministration

In this studywe used a qualitative research approach, data

wereobtainedthroughinterviewsandintegratedwithsecondary

data. Open-ended interviewsconstitute ourprincipal source of

data. In this type of interview, researchers ask questions on

Table1

Characteristicsofthefirmsinthesample.

Company Location Employees Establishedin Coreproduction Company form

Distance fromHonda 1 CaStampi Treglio(CH) 30 1977 Mouldsandmechanicalequipments s.r.l.a 21km

2 Cams FaraF.P.(CH) 39 1975 Mouldsdesignandproduction s.p.a.b 36km

3 Comest Filetto(CH) 35 1986 Mouldsandpartsforcarsandmotorcycles s.r.la 27km

4 Cometa Casoli(CH) 100 1980 Mechanicalpartsandaccessories s.r.l.a 16km

5 Europainting Atessa(CH) 150 1984 Industrialpaining s.r.la 0km

6 F.I.Se.M. Atessa(CH) 58 1989 Seatsandplasticitems s.r.l.a 0km

7 GalvanicaDiTorino Spoltore(PE) 11 1967 Galvaniccoatingandfinishing s.n.c.c 62km

8 Igea Lanciano(CH) 20 1975 Adhesivefilms,shapesandlogos s.r.la 15km

9 Marplastica Lanciano(CH) 65 1987 Plastictechnicalproducts s.r.la 12km

10 Me.Ga. Arielli(CH) 50 1991 Galvanictreatments s.r.la 38km

11 Palena Atessa(CH) 80 1953 Internationaltransport s.r.la 0km

12 TA Casoli(CH) 40 1978 Assemblyandelectricalwiring s.r.la 15km

13 Taumat Atessa(CH) 35 1987 Industrialmechanicalparts s.r.l.a 0km

14 TecnomeccanicaSlid FaraF.P.(CH) 97 1981 Turning,milling,mouldingandmechanicalproducts s.p.a.b 30km

15 T.M.C. Vasto(CH) 50 1987 Mechanicalproducts s.r.la 33km

as.r.l.(societàaresponsabilitàlimitata)=generalpartnership. bs.p.a.(societàperazioni)=publiclimitedcompany. cs.n.c.(societàinnomecollettivo)=generalpartnership.

specifictopics,includingtheparticularpointofviewofthe

inter-viewee (Oppenheim, 2000). The interviews were based on a

semi-structuredquestionnaire,dividedintothreeparts.Thefirst

sectionaskedforadescriptionoftheworkflowinthefirmand,

foreachphase, adescriptionofallthefirm’srelationshipswith

thirdparties.Specialattentionwaspaidtothedescriptionof

con-tentandfrequencyofpersonalandprofessionalrelationshipswith

individuals operatingin otherorganizations(firms, associations

orsimilar) withinand outsidetheconsortium.Thesecond part

of the questionnaire focused on the role of information

tech-nologies (ITs)in business activities.In this section,researchers

specificallyinvestigatedtheimpactofITsontheirrelationships.

Thethirdpartofthequestionnairefocusedonthecharacteristics

of thefirm’s external environment, to captureany special

fea-tureorcontingencythatwouldrenderthefirm’soperatingcontext

uniqueorinteresting.ThequestionnairecanbefoundinAppendix

A.

Wepersonallycontactedalltheconsortiummembersand14

outof15agreedtobeinterviewed.Weconducteda totalof25

interviews,12withgeneralmanagersorCEOsand13withthose

responsibleforotherfunctions(e.g.sales,purchasing,andITs).Alist

ofintervieweesandtheirpositionsisprovidedinAppendixB.

Inter-viewslastedbetween30and75minandwereconductedonsite

betweenFebruaryandApril2007.Alltheinterviewsweredigitally

recordedandtranscribedintheirentiretytoretainallthedetailsof

theconversationsandtoensurethesuitabilityofthedataforthe

contentanalysisprocedure.

5.3. Contentanalysisprocedure

FollowingtheguidelinesprovidedbyKrippendorff(2003),we

identifiedsamplingandcontextunitsofanalysis.Samplingunits

are“unitsthataredistinguishedforselectiveinclusioninan

anal-ysis”(Krippendorff,2003:p.98).Theseunitsmustbeindependent

fromeachother.Ininferentialstatistics,samplingunitsarecalled

observations.Weselectedfirmsassamplingunits:inourresearch

context,firmsaretheunitsthatcanassureindependenceamong

observedvariablessincefirmsareindependentofeachother.

Con-textunitsare“unitsoftextualmatterthatsetthelimitsonthe

informationtobeconsideredinthedescriptionofrecordingunits”

(Krippendorff,2003:p.101):weidentifiedthesentenceasthe

con-textunit.Thechoicetousethesentencewasmotivatedbyaholistic

approachtothetext,requestedbythespecificitiesoftheItalian

languageusedintheinterviews.Italianisrichinsynonymsand

manywordshaveambiguousmeaningsthatcannotbeunderstood

withoutreferencetotheentiresentence.InItalian,asinother

lan-guages,themeaningofawordtypicallydependsonitssyntactical

rolewithinasentence.

Oncetheunits ofanalysiswere defined,onthebasis of the

listofactivitiesandrelationshipsreportedinouranalyticalmodel,

researcherselaboratedasetofrulesthatminimizedthepossibility

that findings would reflect the analysts’ subjective

predisposi-tion rather than the content of the documents under analysis

(Kassarjian,1977).Theserulesarerepresentedbydictionaries,

con-structedasalistofwordsthatintervieweesusedtorefertospecific

concepts(eitheranactivityorarelationship).Thedictionarieswere

constructedasfollows:weextractedalistofwordsappearingmore

than10timesinthetexts,usingtheNVivo7software.Thelist

com-prised776words;aftertheeliminationofarticles,auxiliaries,and

prepositions,andgroupingsingularsandplurals,alistof141words

remained(seeAppendicesCandD).Weassignedtoeachconcept

(activityorrelationship)therelevantwordsfromamongthe141

identified.Toconstruct anexhaustivelistof wordsweusedan

Italiandictionaryofsynonymsandantonyms(Gabrielli,2000)for

eachwordandincludedtherelatedandrelevantsynonymsand

antonymsinourdictionary(seeAppendixE).

Two coders, working independently, proceeded to code the

relevant sentencesusingthetextsearchfunctionintheNVivo7

software.Theymanuallycheckedtheentiretexttocapturecoding

errorsduetothemultiplepossiblemeaningsofwordsortonegative

sentences.InAppendixFwereportthelistofconceptsinvestigated

withthenumberofsourcesandreferencescodedforeach.Sources

arethenumberofsamplingunits(i.e.,thefirms)wherethe

con-ceptswereobservedandreferencesarethecontextunits(i.e.,the

sentences).

5.4. Statisticalanalysis

TheoutputofthecontentanalysisistheWord-Countmatrix

(Table2).TheWord-Countmatrix countsthenumber ofwords

that wereusedinthetextwhile referringtoa specificconcept

andisgenerallyusedtocompareitemsandidentifypatterns.The

construction of the Word-Countmatrix is the starting point of

theanalysis sincewe focusedontheinterconnectionsbetween

activitiesandrelationships.Theconceptswereconsideredin

iso-lation aswellasin theirinteractioneffects, notedwithan* in

thetable:e.g.personal*professional,meaningthatthenumberof

wordsreportedinthematrixweretaggedaspartofapersonalas

wellasaprofessionalrelationship;inotherwords,thesecategories

werecreatedbycountingthenumberofwordsusedtodescribe

professionalrelationshipsaswellaspersonalrelationships(i.e.,the

numberofwordsinthesentencescodedasmentioningboth

profes-sionalandpersonalrelationships).Wefurtherexploredourresults

usingthedatareportedintheWord-Countmatrixtoperform

sta-tistical analysis(suchascorrelations).Toenhancetheclarity of

thediscussion,wereportadescriptionoftheanalysisinthenext

section,togetherwiththediscussionoftheresults.

6. Results

6.1. Roleofclientsandkeyclientsindiffusinginnovation

The analysisof evidence collecteddemonstratesthat Honda

Italiahasacentralrolein professionalactivities.Lookingatthe

listofthemostfrequentwordsininterviewtexts(AppendixC),

wenoticethattheword“Honda”appears273times(secondinthe

ranking).Weexploredtheroleofthiskeyclientastheenablerof

activitiesandfoundthat,despitethelargenumberofoperational

activitiescarriedoutinCISIsrelationshipswithHondaItalia,this

clientalsoplayedacentralroleinthediffusionoforganizational

innovations(Table2).Thematrix reports 992wordsrelated to

organizationalinnovationsandclientrelationships,and822words

fororganizationalinnovationsandtheCISI–Hondarelationships.

In particular,werefer tothejust-in-timepractice(JIT)adopted

byHondaItaliaand diffusedamongallitscontractors.The

cen-tral roleplayed byHondaItaliain encouragingtheadoption of

JITproceduresisrecognizedinmanyinterviews.Accordingtoone

interviewee:“Wefollowajust-in-time approach,andtheclient

[HondaItalia]decidesitsproductionneeds...Wehavetofollow

ourcustomer’srequirements;thisisthegame.”Anothernotes:“We

donothavestorageanymore:weshiptoHondaupto3timesper

day.ThisiswhatHondarequirestolower[their]cost,andwehave

tofollowit.”

On thebasis ofthedataintheWord-Countmatrix,we

con-structedTable3thatdepictstheimpactofeach relationshipon

economicactivities:strategic,innovativeandoperational.Wedid

notincludeinthetablethoserelationshipsthatsupportonlyone

activity.Lookingattherelationshipsthatpromotethediffusion

of innovation, among theseven relationshipswitha frequency

over25%,fourinvolveclients:personal*otherclients(43%);

Table 2 Word-Count matrix: activities * relations. Strategic activities Innovative activities Operational activities Growth Marketing Shared culture TOT Product–process innovations Organizational innovations ITs related innovations TOT Budgeting– planning Design– engineering Purchasing Sales TOT Professional relationships 742 920 1366 2953 1078 1247 3660 5919 1998 1982 5555 8088 15,282 Associations 151 668 753 1497 143 – 295 438 15 48 537 828 1368 Consortium 151 668 753 1497 143 – 295 438 15 48 537 828 1368 Other associations – 157 – 157 – – – – – – – – – Clients 666 468 1107 2166 1046 922 2757 4659 1612 1846 2213 7413 11,248 Honda 547 363 1107 1942 429 822 1407 2692 761 971 1188 5362 7455 Others clients 591 120 178 889 683 255 1745 2583 851 894 1107 3502 5263 Competitors – 18 – 18 – 114 129 243 – 312 586 451 1263 Suppliers 121 190 256 567 32 304 653 1023 706 181 4252 687 4893 Personal relationships 70 – 166 236 182 121 79 343 – 140 218 374 600 Familiar–friendship – – – – 182 – – 182 140 142 282 Geographical 70 – – 70 – 39 79 79 – – 132 171 171 Trust – – 166 166 – 82 – 82 – – 86 61 147 Personal * professional 70 – 166 236 182 82 40 304 – 140 174 299 481 Personal * associations – – 166 166 – – – – – 48 – – 48 Personal * consortium – – 166 166 – – – 48 – 48 Personal * other ass. – – – – – – – – – – – – – Personal * clients 70 – 166 236 182 82 40 304 – 140 174 299 481 Personal * Honda 70 – 166 236 – 82 40 122 – 140 79 166 306 Personal * other clients 70 – – 70 182 – – 182 – – 95 133 175 Personal * competitors – – – – – – – – 140 – – 140 Table3

Wordfrequenciesinpercentagesdividedbyactivities.

Innovative activities Operational activities Strategic activities Personalrelationships 29% 51% 20% Friendship+familiar 45% 55% 0% Geographic 25% 53% 22% Trust 21% 37% 42% Professionalrelationships 25% 63% 12% Personal*professional 30% 47% 23% Associations 14% 41% 45% Consortium 14% 41% 45% Personal*consortium 0% 22% 78% Clients 26% 62% 12% Personal*clients 30% 47% 23% Honda 22% 62% 16% Personal*Honda 18% 46% 36% Otherclients 30% 60% 10%

Personal*otherclients 43% 41% 16%

Suppliers 16% 75% 9%

Competitors 16% 83% 1%

withthataffirmedbyPavittinhisseminalpaper(1984), innova-tionintheautomotivesectorisdrivenbyclientsandisdeveloped incollaborationwiththem,fallingintothecategoryofspecialized suppliers.

6.2. Strategicactivitiesareenabledmostlybyconsortium-related associations

Focusing on theanalysis of strategic activities and relation-shipssupportingthem(thirdcolumninTable3)wenotethatthe

relationshipswiththehigherpercentagesareassociation-related:

personal*associations (78%),consortium (45%) andassociations

(45%).Thisisconsistentwiththenatureofassociationsingeneral

andwiththatoftheCISIconsortiuminparticular.CISIwasborn

withtheaimofsupportingthegrowthofitsmembers:itsactivities

focusonactionsthatcannotbecarriedoutbySMEsinisolation,

suchasbroad-scalemarketingefforts.Thesmallsizeof

consor-tiummembersdoesnotallowthemtoparticipateinbigevents,but

workingtogethertheyincreasetheircontractualpowerandexploit

economiesofscale.Asoneintervieweepointedout:“Ifwewantto

goandparticipateinanexposition,wehavetoinvest30,000Euros.

Noneofushasthepowertoinvestsuchamountsofmoney

with-outbeingsureoftheeffectivereturns.Ifthere are10 ofus,we

spend3000Euroseachandwecaneasilyparticipate.Thisisan

incredibleopportunitytomeetnewpotentialclients”.Thecreation

oftheconsortiumalsoincreasedtheSMEs’powerinthelocal

eco-nomicsystem.Anotherintervieweenoted:“Nowwearethethird

[largest]organizationinValdiSangro.Weareaconsortiumwith

1100employeesandrevenuesof130millionEuros.AfterSeveland

Honda,thereisnoorganizationaslargeasours.We,asacompany,

wereborninachurch,andnow,withtheconsortium,canhave

dis-cussionswithmultinationalsandwehaveanimportantroleinthe

regionaleconomicsystem.”

6.3. Theroleofpersonalrelationshipsinenablinginnovation

Analyzinghowrelationshipssupportinnovativeactivities,four

out of thefive percentages over 30%(Table 3)are represented

bypersonalrelationships:friendshipandfamiliar(45%);personal

relationships*clients–excludingHonda(43%);personal

relation-ships*clients(30%);personal*professionalrelationships(30%).As

wediscussedintheprevioussection,relationshipswithclientsare

themainenablersofinnovativeactivities:thepersonalaspectof

thoserelationshipsincreasestheirinnovativepotential.Thisisan

interestingresultsinceitprovidessupportinfurther

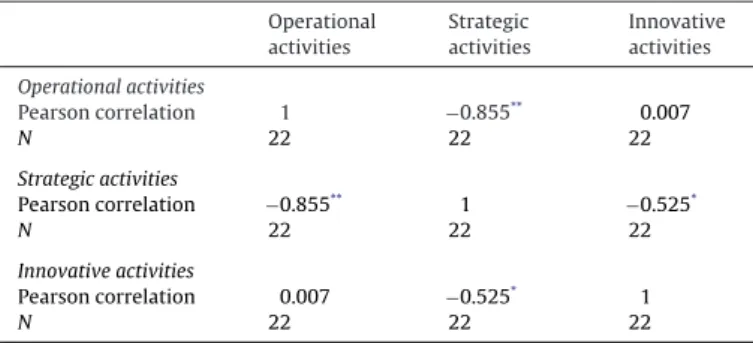

Table4 Correlationtable. Operational activities Strategic activities Innovative activities Operationalactivities Pearsoncorrelation 1 −0.855** 0.007 N 22 22 22 Strategicactivities Pearsoncorrelation −0.855** 1 −0.525* N 22 22 22 Innovativeactivities Pearsoncorrelation 0.007 −0.525* 1 N 22 22 22

*Significantatthe0.05level(2-tailed). **Significantatthe0.01level(2-tailed).

oneintervieweepointedout:“...(whentalkingaboutclients)we

knoweachotheralready,wedevelopedtrustoveryearsofworking

together,theyknowhowweworkandtheytrustourquality.For

thisreason,theyofteninviteustocollaborate,todevelopnew

prod-uctsandimplementnewprocesses.Withotherclientsitisnotthe

same,theysendustheorderandweproducefollowingtheir

guide-lines”.Personalelementsinarelationshipreinforcelinksamong

membersandfacilitatethedisclosureofsensitiveinformationand

advice,suchasthatrelatedtotheadoptionofinnovationswithin

andbetweenCISImembers.Anotherintervieweepointedout:“I

havedelegatedeverythingthatisrelatedtoITstomybrother.After

theinitialdecisionstakenbymyself,datingbackto1984when

weimplementedthefirstsoftwareforindustrialdesign,heisnow

incharge”.Theperceivedriskinvolvedininnovativeactivitiesis

mitigatedbypersonalinvolvementandtrustintherelationships.

Adeeperanalysisof howpersonal relationshipssupportthe

diffusionofinnovation ledustonote thatallthe typologiesof

personalrelationshipsactivelyenableinnovativeactivities.With

theaimoffurtherexploringtheimportanceofmultiplechannels

insupportingactivities,wecalculatedtheHerfindahl–Hirschman

concentrationindextostudythedispersionofactivitiesamong

differentnetworks.Theformulaweusedisthefollowing(1):

HHI=

�

(xi)2 (1)wherexi isthepercentageofthewordcountforeach variable.

TheHHIindexcanrangefrom0to10.000,thelowerthevalue,

thelessconcentratedthephenomenon.Usingthedatafromthe

Word-Countmatrix,weobtainedthefollowingresults:operative

activitiesHHI=3.621;innovativeactivitiesHHI=3.917;strategic

activitiesHHI=5.827.Thelowvaluesassociatedwithinnovative

and operative activities suggeststhat those activitiesare more

widespreadthroughoutpersonalnetworkchannels,whilestrategic

activitiestakeplaceinfewnetworks,mainlydominatedbytrust.

Theresultsalsosuggesttheexistenceofsimilarpatternsbetween

operativeand innovativeactivitiesand differentpatternsin the

caseofstrategicactivities.Wewillexplorethisfurtherinthe

fol-lowingsection.

6.4. Negativecorrelationbetweenstrategicactivitiesand

innovativeactivities

The last analysis performed on the data was the

construc-tion of a correlation tableamong the three types of activities

(Table4).Asignificantnegativecorrelationexistsbetween

opera-tionalandstrategicactivities(−0.855),andbetweeninnovativeand

strategicactivities(−0.525).Weinterprettheseresultsasfollow:

thetypesofrelationshipsrequiredforoperationalandinnovative

activitiesdifferfromthosenecessaryfordevelopingstrategic

activ-ities:strategic activitiesinvolve differenttypes of relationships

comparedtotheothertwoactivities.Oneintervieweepointedout:

“innovativetechnologiesareverysector-specific,ifyouhaveaclose

relationshipwithacompetitor,thenyoucanobtainknowledgeand

information.Inthecaseoftheconsortium,weseldomtalkabout

technologies;wefocusmainlyonorganizationalormarketanalysis

tools.Weworktogetherinorganizingexpos,particularmarketing

activitiesthatinvolveallmembers”.Consequently,strategic

activi-tiestakeplaceindifferentrelationshipnetworks.Infact,dissimilar

setsofrelationships,withadistinctivenatureanddevelopment

patterns,supportthem.

7. Discussionandconclusion

Innovationisdiffusedandadoptedwithinnetworksfollowing

pathsthat aredifficult toidentifyandthoroughlycomprehend.

Previous contributions largely explored this topic by

provid-ing acrucial understandingoftheroleof networksin diffusing

innovation andstudyingtheircriticalcomponents,suchas

net-workcompositions,positionofnetworkedmembers,theroleof

knowledge flows, trust and embeddedness(e.g. Deroian, 2002;

Granovetter,1985;Gulati,1998;Kogut,2000;Laursenetal.,2011; Padgett and Powell,2011;Smith-Doerrand Powell,2004;Uzzi,

1997).Startingfromtheseseminalcontributions,wemoved

for-ward in the understanding of innovation dynamics that occur

withinnetworks,inparticular,exploringtheroleplayedby

per-sonalrelationships.

Theempirical contextselectedfor thestudyis aconsortium

of SMEs(CISI consortium), located incentral Italy. The context

is particularly appropriate since it comprises a largevariety of

relationships,bothhorizontalandvertical,personalaswellas

pro-fessional.Moreover,thepresenceofadominantleader,HondaItalia

inourcase,thatinfluencesthecreationandthedirectionofthis

net-workisanimportantelementthatgivesusausefullenswithwhich

toanalyzethephenomenon.Weanalyzedqualitativedatacollected

withpersonal interviewsusinganoriginalmethod,thecontent

analysisprocedure,whichguaranteesahighlevelofobjectivityand

externalvalidity(Berelson,1952;Kassarjian,1977;Krippendorff,

2003).

The analysis of the results suggests that personal

relation-shipsplayapivotalroleinfacilitatingcontactsamongnetworked

members.Moreover,ourdataalsodescribeshowthediffusionof

innovationtakesplaceandwhatthedynamicsoccurringbetween

activitiesandpersonal/professionalrelationshipsare.Theresults

confirmthecentralrolethatthemainclientplayswithinthe

net-work(inlinewithexisting literature,see:Everett andBorgatti,

2005;Pavitt,1984)andunveilpartiallyunknowndynamics.Our

contributionscanbesummarizedasfollows:(i)thediffusionof

innovationisenabledbypersonalrelationships;(ii)strategicand

innovativeactivitiestakeplaceindifferentnetworks;thelocusof

innovationis notthelocusof strategy:actors,relationshipsand

rationalesinvolvedaredifferent,confirmingtheexistenceof

mul-tidimensionallinks,characterizedbydifferentfunctions;(iii)onthe

onehand,innovativeactivitiesarewidelydiffusedwithinnetworks

exploitingalargevarietyofrelationshipsandinvolvingmultiple

networkdimensions;ontheotherhand,strategicactivitiesdepend

onfewerdimensionsand, alsointhis case,have dynamicsthat

differfromthosethatcharacterizeinnovativeactivities.Ourwork

yieldsimportantimplicationsforscholarsaswellasmanagement

practitionersandpolicymakers,whicharediscussedinthenext

section.

7.1. Implicationsfortheory

Ourfirstfindingcontributestotheresearchstreamexploringthe

oftrust,sharedvalues,andmutualobjectivesfacilitatesthe

com-mencementofadifficultandriskypath,suchasthatcharacterizing

theadoptionofinnovation.Ourempiricalevidenceshowsthatif

personalrelationshipsexistalongsideprofessionalrelationships,

thelikelihoodofstartinginnovativeactivitiesincreases.The

uncer-taintythatcharacterizesinnovation processesis mitigatedby a

firm’sincreasedtrustinitspartners;trustlowerstheriskof

oppor-tunisticbehavioursthatcouldendangerthesuccessofitsbusiness.

Leveraginguponpreviouscontributionsthatexploredtheroleof

trust(Ettlinger,2003;Lorenzen,2001;Uzzi,1997),wesupportthe

centralityplayedbythepersonaldimensioninrelationshipsand,

withthisfinding,reinforcetheroleofpersonalrelationshipsin

dif-fusinginnovation.Previousstudieshavesuggesteditsimportance,

butnonehasthusfarproveditscentralityandthesuperior

innova-tionpotentialofpersonal-basedrelationships.Webelievethatthis

contributionwillshedfurtherlightonthesocialunderstandingof

innovation,alsoindicatinginterestingavenuesforfutureresearch

thatwillbediscussedinthenextsection.

Thesecondcontributionaddressesinterrelationsamong

multi-plenetworks.Wefoundanegativecorrelationbetweenstrategic

activitiesandoperationalandinnovativeactivities.Thisindicates

thatsuchactivitiesoccurindifferentsettings.Thecontextsinwhich

strategiesarediscussedandexecuteddifferfromthoseinwhich

operationalandinnovativeactivitiestakeplace:channelsof

com-munication,locations,andsocialenvironmentsaredistinct.This

findingreinforcespreviouscontributionsinthearea(e.g.Sammarra

andBiggiero,2008)andbroadensourunderstandingofthe

interre-lationsbetweenknowledge,activitiesandnetworks.Strategicand

innovativeactivitiestakeplaceindifferentsettings:thelocusof

innovationisnotthelocusofstrategy.Differentactors,relationships

andrationales involvedin strategic,operational andinnovative

activitiesconfirmtheexistenceofanetworkofmultidimensional

links.Eachsetoflinksischaracterizedbydifferentfunctions.With

this findingwe gain furtherunderstanding of the

multidimen-sionalstructureofnetworks(Padgettand Powell,2011).Hence,

eachdimensionplaysadifferentrole and,accordingtoitsown

characteristics,ismoreappropriateinsupportingspecificactivities.

Thethird findingcontributes totherolethat multipleactors

in networks play in affecting innovation dynamics. Innovative

activitiesaresponsoredbymultipleactors;theyarewidely

dif-fusedwithinnetworks,exploitingalargevarietyofrelationships

andinvolvingmultiplenetworkdimensions.Ontheotherhand,

strategicactivitiesdependonfewerdimensions,showingalsoin

thiscasethatthenetwork dynamicsaffecting themdifferfrom

thosethatcharacterizeinnovativeactivities.Thedatasuggeststhat

strategicdecisionsaresupportedbyalimitednumberof

relation-shipsandfewactorsinfluencestrategicactivities.Theimplications

ofthesefindingsareparticularlyimportantbecausetheyexpose

structuraldifferencesonhownetworkssupportactivitiesin

dif-ferentways,broadeningcurrentunderstandingofcollaborations

andnetwork structures in business environments.Molleret al.

(2005)pointedouttheimportanceofunderstandingnotonlyhow

businessnetworksare structured,but alsohowtheyshouldbe

managed.Previous studieshavealready investigatedwhysome

innovationsarediffusedslowerthanothers(Deroian,2002).We

believethatthediffusionofinnovativeactivitieswithinnetworks

isapossiblecause.Themultidimensionalityofnetworksspeeds

upthediffusionofinnovations:innovationssupportedbymultiple

networksaremorelikelytobeadoptedanddiffusedfaster.

In addition tothetheoretical contributions discussedso far,

positionedinthecurrentdebateoninnovationandnetwork,this

workalsocontributestotheresearchmethodologyfield.Infact,we

analyzeddatausingcontentanalysis,aresearchmethodscarcely

deployedinmanagementandeconomicliterature(Duriauetal.,

2007;SonparandGolden-Biddle,2008).Untilnow,thisapproach

hasbeenprimarilyusedfortheanalysisofspeechesandinterviews

in the sociology and psychology fields. The use of this

tech-niquepresentsadvantages, especiallyin termsofreliabilityand

explorationofdata.In applyingthismethod,wefollowedstrict

guidelines tolimit arbitraryjudgments and personal decisions:

theuseofvocabularies,listofnodes,codingproceduresandword

counttoolsenhancedobjectivityand,thus,thereliabilityofour

study(Krippendorff,2003).Wemadeextensiveuseofthe

Word-Countmatrix,apowerfultooltodisclosedynamicsandevidences

thatcouldbeoverlookedwhenusingdifferentresearchtools.We

objectivelymeasuredthestrengthoftherelationsexistingbetween

concepts,asexpressedinthespokeninterviews,investigating

qual-itativedatafromadifferentperspective.Wehadtheopportunityto

exploreandidentifynewresearchhypothesesandgather

empiri-calevidence,makinginferencesfrominterviewtexts,alsowhen

intervieweesdidnot explicitly statethose relations.

Paraphras-ingBerelson(1952),wedescribedinanobjective,systematic,and

quantitativewaythemanifestcontentofcommunications.

7.2. Implicationsformanagementpractitionersandpolicy

makers

Theunderstandinggainedonthedynamicsofinnovation

dif-fusionisparticularlysignificantformanagerswillingtopromote

thediffusionofinnovativepracticesandforpolicymakerswanting

todevelopappropriatestrategiestoincreasetheinnovativenessof

firms.

Theimportanceofpersonalrelationshipsinfavouringthe

adop-tionofinnovationsisakeyaspectthatmanagersshouldconsider

whenencouragingtheirbusinesspartners(e.g.clientsor

suppli-ers)toadoptnewtechnologiesornewproductiveprocesses.We

foundthat,inthesecases,theexistenceofpersonalrelationships

betweenpartnersfacilitatesthesuccessofthediffusionand

adop-tionofinnovation,increasingthefirms’competitiveness.Moreover,

toincreasethelikelihoodoftheadoptionofaninnovativepractice,

informationonnewpracticescouldbeofferedinthosesettingsin

whichoperationalactivitiesareperformed.Thus,tobeeffective,

communicationanddiffusionshouldtakeintoaccounttheroleof

theworkerswhoperformoperationalactivities,since,asour

find-ingsdemonstrate,operationalandinnovativeactivitiesarelikely

tooccurinthesameworkingcontext.

7.3. Limitationsandresearchagenda

Nevertheless,thisstudyhascertainlimitationsarisingfromthe

casestudymethodologyfollowed.Theresearchinvolvesasingle

casestudy,whichlimitsourabilitytogeneralizeourfindings.To

enhancethegeneralizabilityoftheresults,areplicationofthecase

studyusingthesamemethodologyissuggested.Suchareplication

wouldallowresearcherstodeterminewhethertheresultsofthe

presentstudyareduetospecificcontingenciesoffirmoperating

contextsoraregeneralizabletodifferentcontexts.Toincreasethe

generalizabilityoftheresults,itmayalsobepossibletostructure

quantitativedatacollection(e.g.bymeansofasurvey)inorderto

capturethecharacteristicsofthesamephenomenononalarger

basis, indifferentsectors andgeographical contexts.Theriskis

loosingsomeoftheadvantagesandthewealthofdetailobtained

throughtheuseofinterviews,butitwouldbepossibletotestthe

validityofthefindingsviaadifferentmethodologicalapproach.

Asecondsetoflimitationsisduetothecharacteristicsofthe

chosenempiricalcontext.Mostofthefirmsarelocatedinaclose

area,andoperateinthesamesector(automotive).Moreover,most

ofthefirmswerebornasHondaItaliacaptivesuppliers,sharing

similarvisionsandmissions. Insuchasetting, asharedculture

characterizestheindustrialmodelandthismightaffectthe

gen-eralizabilityofthestudy.Thislimitationreinforcestheimportance

Finally,thisstudyalsoindicatesavenuesforfutureresearches.

Themultidimensionalityofnetworksandthecentralroleof

per-sonalrelationshipsininnovationdiffusiondynamicscallfornew

studiesaimedatinvestigatingtheimportanceofthesephenomena.

Infact,theauthorsbelievethatthepapershedslightsoncrucial

dynamics that deserve furtherattention: under which

circum-stancesdopersonalrelationshipsexpresstheirroleasfacilitatorsof

thediffusionofinnovation?Andwhataretheexternalandinternal

contingenciesthatmaylimittheirefficacy?Towhatextentdothe

activitiesofmultiplenetworksoverlap?Howcanthisoverlapbe

exploitedbypolicymakerswhowanttoincreasethediffusionof

innovationandthecompetitiveadvantageofnetworksoffirms?

Theseare onlya fewof thequestions thatmayarise fromthis

presentstudyandwebelievedeservefurtherinvestigation.

Acknowledgments

Author’snamesareinalphabeticalorder.Theauthors

acknowl-edgethefinancialsupportoftheItalian MinistryforEducation,

UniversitiesandResearch(FIRB,RBNE05FKZ2:TEKNE–Towards

EvolvingKnowledge-basedinterNetworkedEnterprise).

The authors want to thank Micheal Hobday, John Padgett,

AndreaPrencipefortheirvaluableadvicesonearlierversionsofthe

manuscript;DajanaD’Andrea,FrancescaMasciarelliandthe

partic-ipantstothePDWonFirms,EcosystemsandInnovationorganized

byRahulKapoorandAnneParmigianiatAOM2010inMontrealfor

theircommentsandencouragement;AlbertoSimboliforthehelpin

thecollectionofthedata.TheyarealsogratefultotheeditorMartin

Kenneyandthetwoanonymousreviewersfortheirprecious

feed-backthatreallyincreasedthevalueofthework.Allerrorsremain

theauthor’sown.

AppendixA. Questionnaire.

Introduction

1.Couldyoupleasedescribeyourfirm’shistoryandactivity?

2.Pleaseexplainyourfirm’sworkingprocesses,fromrawmaterialpurchases tosalesandpost-saleservices,suchasmaintenanceactivities(ifany). Relationships

Foreachphaseoftheworkingprocess,pleaseexplain:

3.Whichfirm/individualdoyou/yourfirm/youremployeesrelateto? 4.Howoften?

5.Whichtypeofrelationships(e.g.:formal,informal,contractual)? 6.Howdoyou/yourfirm/youremployeesinteractwiththirdparties(e.g.:

phone,email,letters,face-to-face) 7.Howlongdothemeetingslast? Inparticular,describeyourrelationshipswith: 8.Occasionalsuppliers

9.Preferredsuppliers 10.Clients

11.Othermembersoftheconsortium 12.Competitors

13.Otherrelevantrelationships Informationtechnology

14.DoyouuseITs?Which?(e.g.:ERP,Internet,email,...) 15.DoanyofyourprocessesrequireITssupport? DoyouuseITstorelatewith:

16.Clients? 17.Suppliers?

18.Othermembersoftheconsortium? 19.Other?

20.Couldyoupleasedescribehowyouusethem? Externalenvironment

21.Whatarethevariablesofyourcompetitivecontextthatdifferentiateyour firmfromtheotherfirmsoftheconsortium?

22.Andfromotherfirmsintheautomotiveindustry?

23.HavesomeofthosevariablesinfluencedtheadoptionofITs?Willsomeof theminfluencetheadoptionofITs?

AppendixB. Interviewinformation.Datacollectedby

FedericaCeci(FC),AlbertoSimboli(AS),andDanielaIubatti

(DI).

Nameoftheinterviewee Role Company Location Interviewer

1 PietroRosica GeneralManager Cometa Atessa AS–FC

2 GabrieleScalzi Marketing&Sales Cometa Atessa AS–FC

3 MarioDiCintio SalesandPlanning Cometa Atessa AS–FC

4 PalmerioGiuseppe Purchasing Cometa Atessa AS–FC

5 MarioLorenzi GeneralManager Taumat Atessa AS–DI

6 MaurizioSciocchetti SalesManager Me.ga. Arielli AS–DI

7 VitoPocetti GeneralManager Igea Lanciano FC–DI

8 GiuseppeGiancristofaro QualityManager Igea Lanciano FC–DI

9 EttoreLiberatoscioli CEO LaTecc. FaraF.P. FC–DI

10 DonatoDiNardo SalesManager Comest Filetto FC–DI

11 GabrieleTumini GeneralManager TMC Vasto AS–DI

12 SergioDiCampli Purchasing TMC Vasto AS–DI

13 LucianoTilli SalesandPlanning TMC Vasto AS–DI

14 LucioPalena GeneralManager Palena Atessa AS–DI

15 AnnacarlaPalena Administration Palena Atessa AS–DI

16 AndreaCasalanguida GeneralManager Castampi Roccas.g. AS

17 FlorideoPanaccio GeneralManager Cams FaraF.P. AS–FC

18 MaurizioCocco GeneralManager TA Casoli FC–DI

19 BarbaraMadonna Administration TA Casoli FC–DI

20 FabioDiTommaso Purchasing TA Casoli FC–DI

21 AlfonsoTrozzi CEO Fisem Atessa AS–DI

22 RosannadiNuzio Sales Fisem Atessa AS–DI

23 AntonelloDiTonno GeneralManager Galvanica Spoltore AS–FC

24 MicheleRomagnoli GeneralManager Europainting Atessa AS–FC