Internationalisation and Bioenergy

Effects on Economic Growth

Danilo Audiello

PhD School Coordinator:

Prof.

Francesco

Contò

Supervisor:

Dr Caterina De Lucia

Co-Supervisor:Dr Pasquale Pazienza

2015

D

OCTORATEO

FR

ESEARCHI

NE

CONOMICSA

NDL

AWO

FE

NVIRONMENT,

R

EGIONA

NDL

ANDSCAPEXXVII CYCLE

U

NIVERSITY

O

F

F

OGGIA

2

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisors Dr Caterina De Lucia and Dr Pasquale Pazienza that together with the coordinator Prof. Francesco Contò and Prof. Vincenzo Vecchione, have meticulously guided me through this challenging, yet rewarding academic trip. This work is dedicated with love to my family for their encouragement in all my endeavours, and more specifically to my parents for their dedication and support in my educational steps and grandparents for their confidence in me and for the value they placed on family.

3

Declaration

I hereby declare that my dissertation entitled “Internationalisation and Bioenergy: Effects on Economic Growth”, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctorate of Research degree in Economics and Law of Environment, Region and Landscape, is the result of my own work, except for where it is explicitly attributed to others in the text.

A book chapter, entitled “Second generation biofuels: opportunities and challenges for the development of rural areas” in the Compendium of Energy Science and Technology of Studium Press LLc, USA, is derived partially from Chapter 2 and is currently under peer review.

A poster, entitled “The impact of EU’s CAP on the economic development of Italy”, was presented in the annual Economics Conference of the Lord Ashcroft International Business Department of Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, UK, in December 2013.

An early work, entitled “Biofuels supply chains: sustainability and entrepreneurship in local agricultural systems” was delivered at the 73rd International Atlantic Economic Society, in the

4

5

Abstract

Existing literature evidence suggests a strong relationship between internationalisation and economic growth, as well as a link between biofuel production and economic growth for various clusters of countries, including the members of the Eurozone. As Eurozone policy is shaped with a special focus on internationalisation and well defined directives on bioenergy, their actual effect on economic growth needs to be further investigated.

This dissertation aims firstly to evaluate the impact of internationalisation, as represented by foreign direct investments (FDI) and trade openness, and secondly to measure the effects of bioenergy production, as represented by the daily volume of total biofuel production, on the economic growth, as represented by the growth rate of real gross domestic product (GDP), of the Eurozone.

The analysis is conducted by employing the methods of linear regression, under the exogenous growth theory. The research methodology implies a quantitative analysis of economic data collected from the World Bank and OECD, for the period from 1991 to 2013. In addition to this, the model includes several control variables such as labour force, technology, fixed capital formation and the savings rate.

The results of the research reject the hypotheses of the significant effects of internationalisation and biofuel production on economic growth in the Eurozone. The factors that appear to affect economic growth are the growth of gross fixed capital, inflation, human capital and savings.

7

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 5 1. Introduction ... 11 1.1. Background Information ... 111.2. Aims and Objectives ... 14

1.3. Original Contribution ... 14

1.4. Structure ... 16

2. Literature Review ... 17

2.1. Theories of Economic Growth ... 17

2.1.1. Exogenous Growth... 17

2.1.2. Endogenous Growth... 20

2.2. Empirical Evidence ... 24

2.2.1. Economic Growth and Trade ... 24

2.2.2. Economic Growth and FDI ... 29

2.2.3. Economic Growth and Bioenergy ... 33

2.2.4. Other Determinants of Economic Growth ... 45

2.3. Summary of Literature Review ... 50

3. Methodology ... 53

3.1. Philosophy... 53

3.2. Approach ... 54

3.3. Design ... 55

3.4. Data and Methods ... 57

8

4. Analysis and Discussion ... 63

4.1. Presentation of Variables ... 63

4.2. Fixed and Random Effects Regressions ... 67

4.3. Diagnostic Tests ... 73

4.4. Dynamic Panel Regression with Instruments ... 77

4.5. Bioenergy and GDP Growth Model ... 80

5. Conclusions and Recommendations ... 89

5.1. Discussion ... 89

5.2. Recommendations and Policy Implications ... 99

5.3. Conclusion ... 102

9

List of Figures

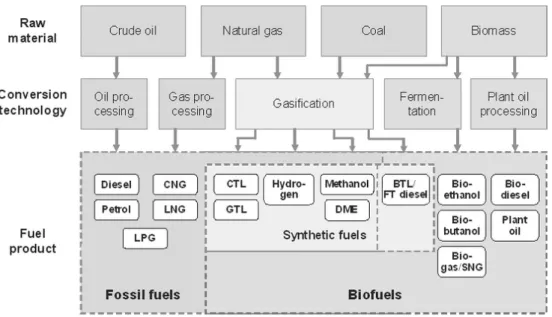

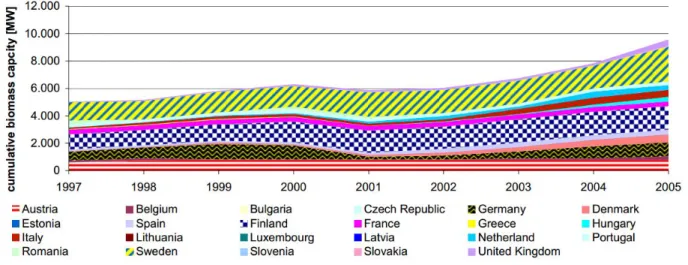

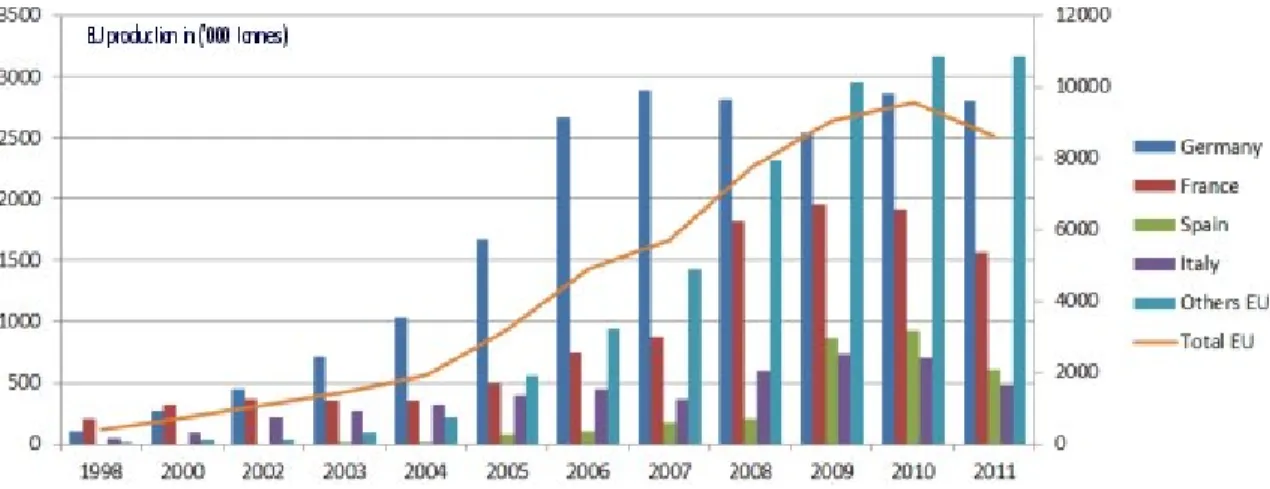

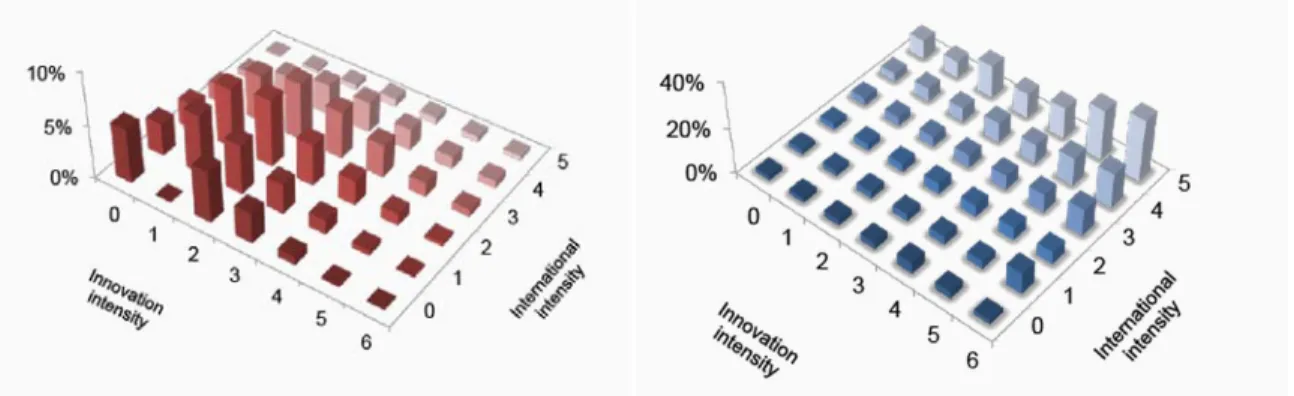

Figure 1: Methods of producing biofuels from biomass. (Festel, 2008) ... 35 Figure2: Historical development of cumulative installed biomass capacity in EU27 countries (Eurostat, 2014) ... 36 Figure 3: Total EU27 biodiesel production for 2010 was over 9.5 million metric tons, an increase of 5.5% from the 2009 figures. (EBB, 2014) ... 42 Figure 4: Share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption of 2005 (left) and 2012 (right) presented as a percentage on the heat map. (Ragwitz, 2006) ... 42 Figure 5: Total realisable potentials (2030) and achieved potential for renewable energy sources for electricity generation (RES-E) in EU-27 countries on technology level. (Ragwitz, 2006) ... 43 Figure 6: Innovation and internationalisation share of firms (left) as compared to the share of employment by intensities (right). (Altomonte, 2014) ... 47 Figure 7: Normality of Residuals’ Distribution ... 76 Figure 8: Bioenergy Model Normality of Residuals' Distribution……….………….86

10

List of Tables

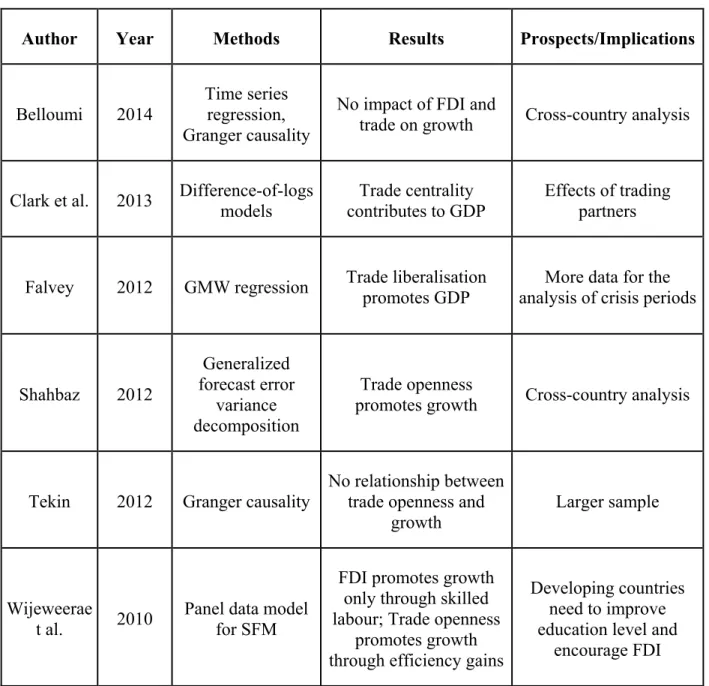

Table 1: Summary of Literature Review ... 50

Table 2: States adopted in the Eurozone ... 57

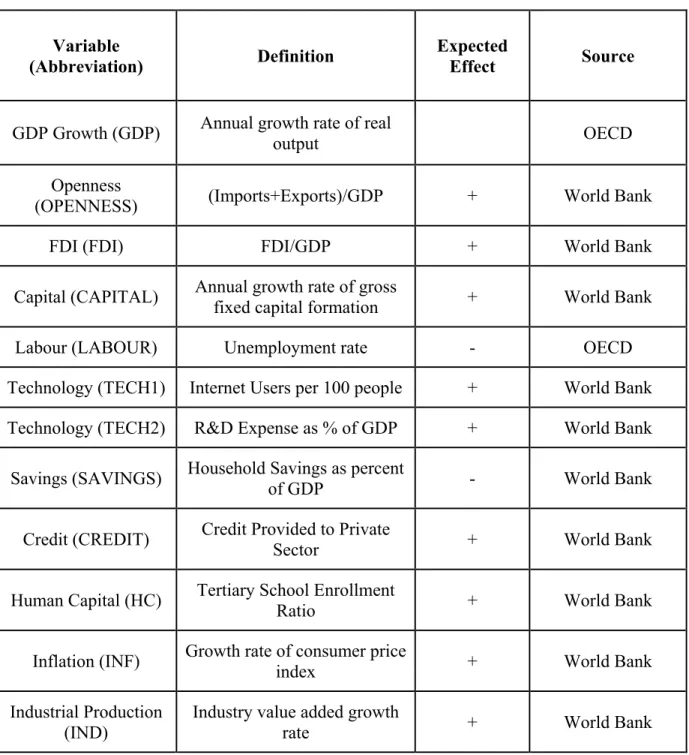

Table 3: List of Variables ... 58

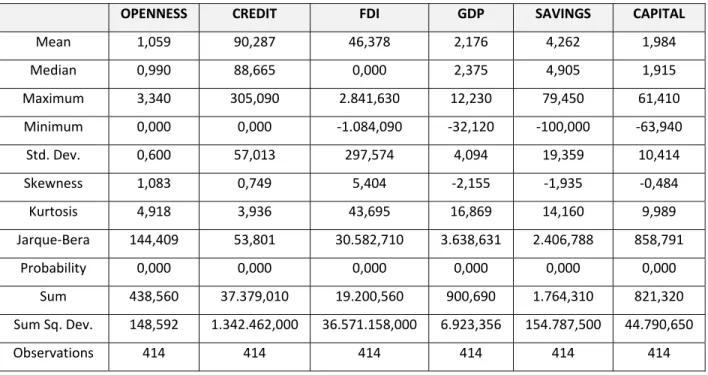

Table 4: Internationalisation Descriptive Statistics ... 64

Table 5: Internationalisation Pooled Regression Summary Statistics ... 67

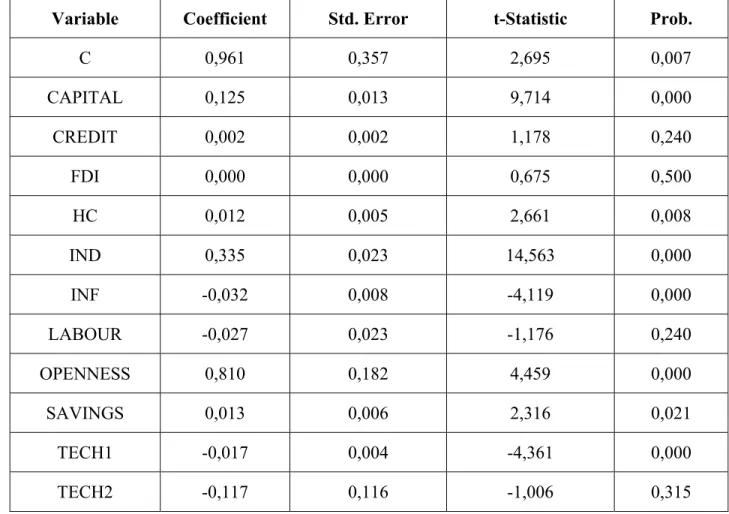

Table 6: Internationalisation Pooled Regression Parameters ... 69

Table 7: Internationalisation Fixed and Random Effects Regressions ... 71

Table 8: Internationalisation Hausman Test ... 73

Table 9: Internationalisation Multicollinearity Test ... 74

Table 10: Internationalisation Final Fixed Effects Model Summary Statistics ... 77

Table 11: Internationalisation Final Fixed Effects Model ... 78

Table 12: Internationalisation Arellano-Bond Dynamic Panel ... 79

Table 13: Production of Bioenergy (in thousand barrels per day). ... 81

Table 14: Bioenergy Pooled, Fixed, and Random Effects Models ... 83

Table 15: Bioenergy Model Hausman Test ... 84

Table 16: Bioenergy Model Multicollinearity Test ... 85

Table 17: Bioenergy Adjusted Random Effects Model ... 87

11

1. Introduction

1.1. Background Information

A definition of economic development is not easily constructed, as there are large disparities in natural endowments, structures of financial markets, cultural aspects, as well as political and social institutions that are observed across regions. Therefore, any attempt to determine a single criterion that distinguishes a developed from a developing country may be invalid. Economic development and economic growth can be expressed by numerous variables and concepts, as well as be determined by a range of factors. However, even the approaches that combine various indicators of economic development are often unsatisfactory, because they include excessive number of variables and become descriptive rather than analytical. Economic growth can be represented by per capita income, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, or GDP growth. The variety of approaches to measuring the level of economic development and the degree of economic growth complicates the process of economic analysis and the estimation of the factors that contribute to economic growth (Nafziger, 2012).

Economic growth is explained by different theories that sometimes contradict each other or complement each other, but no single theory is able to fully explain the concept of economic development (Sardadvar, 2011). At the same time, globalisation trends substantially increase the significance of internationalisation in the context of countries’ economic development. Internationalisation can be reflected in the level of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) that countries send and receive and in the patterns of exports and imports between countries. Trade liberalisation and trade openness can be significant determinants of economic growth, although there is a wide range of other factors that can positively affect development. At the same time,

12 the patterns of economic growth and the factors that determine it can be different in various countries. Moreover, the differences can be observed not only between the developed and developing economies, but also across the countries with similar degrees of economic development. This assumption is tested in the present study by comparing the outcomes from the developed economies of the Eurozone with the findings of other scholars about the effects of internationalisation on economic growth in other countries.

The role of governments and central banks has always been a controversial question in public debate. Nevertheless, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis the debate has become especially escalated. During the last decades, neoliberal thinking1 had become more popular, as

unregulated markets and deregulation along with opening-up and privatisation were favoured. Many proponents of neoliberalism argued that human nature and the concept of modern political institutions were such that more constrained governments were more efficient for the economy (Boas, 2009; Aminzade, 2003; Wilson, 1994). The push for a minimal state that promoted business increased with globalisation. Numerous neoliberal reforms in developing countries were undertaken under pressure from international agencies, including the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organisation (Chang, 2003). However, less attention has been paid to more developed countries with regard to the liberalisation of their trade regimes, their openness for trade and foreign investments.

Besides the effects of internationalisation on economic growth, this research is focused on the contribution of the bioenergy production in the Eurozone on economic growth. The reason why

11 While the term was first introduced by Alexander Ruestow in 1938 and the usage of the term was altered in time,

David Harvey in his “Brief History of Neoliberalism” gives the following definition: “… in the first instance a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets and free trade” (Harvey, 2005, p.2).

13 this factor is taken into account because the European Union has been working on the energy security and diversification of the sources of energy that would help the countries to reduce the costs.

Bioenergy produced from renewable sources attracted much attention in the society and academic world. The first generation biofuels face direct competition with food production (Martin, 2010), while problems such as biodiversity conservation and environmental consequences of bioenergy production are often greater than the outcome of fossil fuels (Gasparatos, 2013). These problems need to be addressed by the second generation biofuel technologies that use not only agricultural food products such as oils, starch and sugar, but also compounds used in the generation of fuel and energy. The second generation fuels can ensure higher conversion efficiency. These positive impacts are especially important in the agricultural sector, in which the Eurozone has a common policy among its members. Future economic development of the Eurozone can be determined by the change in the production of the second generation biofuels. The present dissertation analyses the possible effects of biofuels, produced by first generation technologies, on economic growth in addition to the effects of internationalisation. The objectives of the study are to assess economic effects of the total production of biofuels.

Thus, the present study explores a wide array of factors that influence economic growth of the Eurozone. Among these factors, a special attention is paid to the effects of the bioenergy production and internationalisation represented by the FDI inflows and trade openness. This region has been selected as an objective of the research because the countries have a common currency and no barriers to trade among them. Furthermore, some members of the Eurozone such as Greece and Spain suffered considerably during the European Debt Crisis. Thus, the findings

14 from this research will also have implications for the recovery of the Eurozone economy through internationalisation. It will be shown whether the latter factor can significantly affect economic growth in the region. In turn, the answer to this question will help politicians to make decisions in regards to further internationalisation of the Eurozone by attracting more FDI and removing trade barriers with other countries.

1.2. Aims and Objectives

The aim of the present research is to assess to what extent internationalisation and bioenergy production affected economic growth of the Eurozone. The objectives are:

To investigate the impact of the openness to trade on economic growth of the Eurozone; To evaluate the impact of the FDI inflows on the economic growth of the countries of the

Eurozone;

To measure the effects of biofuel production on economic growth of the countries of the Eurozone.

1.3. Original Contribution

The present study expands the existing literature that has analysed the determinants of economic growth and specifically the effects of internationalisation on economic development. Previous investigations were mainly focused on the effects of internationalisation on the performance of companies (Giovanetti et al., 2013; Mayer and Ottaviano, 2008; Bertolini and Giovanetti, 2006). The current study aims to go beyond the firm level and to assess the impact of internationalisation on the economic growth of the countries that currently comprise the Eurozone. Furthermore, internationalisation is represented by two variables that include FDI and trade openness. While numerous studies explored the effects of these variables on economic

15 growth for samples of countries (Eller et al., 2006; Hermes and Lensink, 2003), the current investigation undertakes a cross-country analysis that is focused specifically on the Eurozone economies. The contribution of the study to the academic literature would be reflected in the cross-country observations on the effects of internationalisation on economic growth.

Many previous studies explore the determinants of economic growth and particularly the effects of internationalisation for developing countries (Schneider, 2005; Beck, 2002). This research contributes to literature by estimating the effects of internationalisation and bioenergy production on the developed economies. The findings could be valuable both for academic scholars who investigate the same question and to regulators and policy makers who are responsible for economic growth. The findings can be valid not only for the case of the Eurozone, but they can also be extrapolated to other developed countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)2. Furthermore, the discussion of the study includes the comparison of

the observations of the present research with the conclusions that were obtained for developed economies. This could provide valuable insights about the peculiarities of the developed and developing countries. The assumptions about the factors that contribute to economic growth at different stages of economic development can be applied by regulators and policy makers from different countries.

2The member countries of the OECD are, as of 2014, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic,

Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxemburg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, UK and USA.

16

1.4. Structure

After presenting above a brief introduction and background to the study, including a description of the main aims and objectives of the current research, the dissertation will subsequently be organised according to the following structure:

Chapter 2 describes the main literature review by focusing on economic growth theories and discusses the empirical findings of numerous studies that explored the respective growth theory question. The review explored various factors affecting economic growth in different countries. Special attention is paid to internationalisation factors, including openness to trade and FDI;

Chapter 3 illustrates the methodology used in the current thesis. It reflects the design, philosophy, approach and methods of the research;

Chapter 4 shows the quantitative approach through a case study and presents the main findings of the investigation;

Chapter 5 discusses the results obtained in the previous chapter and compares and contrasts these ones with current literature in the context of the growth theories;

Finally, Chapter 5 summarises, concludes and provides policy implications and recommendations for future investigations.

17

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theories of Economic Growth

Internationalisation can be defined as an expansion of interactions of the country and its businesses with the outside world. This chapter provides a review of the key theories of economic growth and internationalisation. The latter is divided into international trade and foreign investments. The theories reviewed started from the classical growth theory and the theory of absolute advantage and progress to more advanced theories that are currently used by economists (Arestis et al., 2007). Empirical evidence is provided to explore the findings about the relations between internationalisation, FDI, international trade and economic growth.

2.1.1. Exogenous Growth

The models of economic growth are generally divided into exogenous and endogenous. The classical theory is based on the works of Adam Smith who underlined the significance of increasing labour productivity and saving and developed the theory of absolute advantage (Sardadvar, 2011). The theory of absolute advantage assumed that a trade between two nations is based on mutual benefits to the countries. The trade that delivers gains to both parties is based on absolute advantage. The efficiency of one nation in the production of a commodity leads to specialisation in the production and to the absolute advantage that creates trade (Zhang, 2008). The Neo-Classical school of economics suggests that economic growth is exogenous and determined in the long run by capital accumulation and capital flows, labour market and productivity (Sengupta, 2011). The neo-classical growth model rests on several assumptions. Firstly, the model assumes that the labour force and labour-saving technical progress have a

18 constant exogenous rate. Then, the model does not take into consideration that there can be an independent investment function and assumes that all saving is invested. Furthermore, the model has an assumption that output is a function of labour and capital. At the same time, the production function demonstrates constant returns to scale, while diminishing returns to individual production function are observed (Thirlwall, 2003).

The Solow-Swan model is the most popular exogenous growth theory that has roots in the Cobb-Douglas production function (Dohtani, 2010). The Solow-Swan model views technological progress as a driver of economic growth whereas other exogenous growth theories such as the Harrod-Domar model view the savings rate in the economy as the main driver of economic growth (Huh and Kim, 2013). Meanwhile, the critics of the Solow-Swan model argue that it is hardly possible to define capital independently of capital goods. Furthermore, reasoning purely in terms of capital value can be not appropriate, as capital may take the form of various commodities (Foley, 1999). The Harrod-Domar model is criticised for the fact that while savings and investment are necessary for economic development, they are not sufficient conditions. Furthermore, the assumption of constant returns to scale can be criticised as well (Mayawala, 2008).

The neoclassical model predicts that under the environment of the steady state, the level of output per capital has positive relations to the ratio of savings to investment. Besides, it has negative relations to the growth of population or labour force. Furthermore, the theory suggests that the growth of output does not depend on the savings-investment ratio. Instead, it is determined by the exogenously driven labour force growth rate that is expressed in efficiency units. This prediction is based on the fact that higher level of savings-investment ratio is offset by a higher ratio of capital to output or a lower level of capital productivity. The predictions are

19 based on the assumption of diminishing returns to capital. When the savings ratio and production function are the same, an inverse relation across economies between the ratio of capital to labour and capital productivity would be observed. This implies that poorer countries should grow faster than rich nations. This leads to the convergence of incomes per capita across the globe (Westernhagen, 2002). However, the prediction of the convergence in per capita incomes is inherent to the developed economies, while for the developing countries and for the world as a whole this assumption does not hold true. Average incomes in the poor countries do not demonstrate rapid growth that could catch up to the incomes in the rich countries (Neuhaus, 2006).

The neo-classical model can be criticised from different points of view. Firstly, in the real world appropriate government policies, including liberalisation of trade, promotion of domestic savings, and removal of distortions in the domestic market may permanently increase the degree of economic development. However, the neo-classical model assumes that such policies are able to have only a temporal effect. The model does not take into consideration the differences in overall technological efficiency, savings rate and labour force growth rate in different countries. In the long run the level of income per capital depends on these factors. This means that different countries should be expected to converge to different levels of income per capita. Some rich countries grow faster than some poor economies, and this fact contradicts the neo-classical growth model (Boland, 2005). Moreover, the model does not pay attention to the prominent feature of structural change during the process of economic growth. Nevertheless, the model is applicable to advanced economies that are close to the conformity with the assumptions of the theory (Elson, 2013).

20

2.1.2. Endogenous Growth

An alternative view on economic growth is put forward by the endogenous growth theory (De Liso et al., 2001).This is a rather new approach compared to the exogenous growth theories. The endogenous growth theory is different from the neo-classical approach in that the former views human capital, spillover effects and innovation as the main internal drivers of economic growth in the long run (Romer, 2011). Internationalisation is generally viewed as a factor of economic growth in the context of neo-classical exogenous growth models. Endogenous theory implies that the accumulation of knowledge is important for economic growth, while this factor is not considered in the neo-classical growth models. Knowledge is viewed as a public good in the Solow-Swan model, but under the endogenous growth model, localised knowledge accumulation is possible (Roberts and Setterfield, 2010).

The endogenous growth model was developed as a reaction to several inconsistencies. For example, economic theorists suggested that technological change was important for growth, while income distribution showed that the reliance on the assumptions of free distribution of knowledge and perfect competition were not appropriate for the justification of growth (Capron, 2000). Under the new growth theory technological progress is endogenised as companies operate in the markets under imperfect competition. Meanwhile, there are different approaches to endogenous growth. Some theories include non-convexities or externalities, while some are based on convex models. Nevertheless, endogenous growth theory is aimed at explaining the divergence in income across countries and determines the origin of growth. One of the key outcomes of endogenous growth theory is that policy measures are able to affect the long-term economic growth rate. This is often achieved by higher levels of savings and investment, new technology and human capital. These phenomena lead to the growth in return to scale and

21 explain divergence in economic performance. This major contrast to exogenous growth models explains the popularity of endogenous growth theory (Stimson et al., 2010).

Despite the factors that are taken into account by the endogenous growth theory and are not considered by the exogenous theory, there are arguments that the neo-classical model is able to explain most of the cross-country differences in output per person (Aghion et al., 1998). There was evidence that countries were converging to similar growth paths in accordance with the Solow-Swan model. At the same time, the growth that is based on technological innovation and research and development can be viewed as less valid, since capital accumulation is a more prominent source of growth (Aghion et al., 1998). Specifically, in the post-war period research and development inputs have increased substantially, while no tendency for the growth of productivity was observed. However, the effects of FDI and exports on growth are limited under the exogenous theory, while endogenous theories provide a framework in which FDI can permanently influence growth rate in the host economy through technology and knowledge transfer (Zheng et al., 2006).

Both exogenous and endogenous growth models are based on the assumptions that are made by individuals with perfect information. However, this significantly contradicts the modern view that is expressed in expectations theory. The theory assumes no perfect information and suggests that people process information to develop expectations. Rational expectations theory suggests that companies that expect diminishing profits or losses would not invest when a positive demand shock is observed. Therefore, the demand shock would be reflected in price changes only. Thus, rational expectations paralyse action and prevent economic growth and business cycles (Brouwer, 2012). Expectations theory implies that negative expectations lead to the absence of natural growth, while the major causes of limited growth are the expectations

22 themselves. Negative expectations are viewed as self-fulfilling prophecies. However, expectations theory is not able to explain the causes of natural productivity growth (Arnold, 2013). Expectations can be viewed as informed forecasts of future events, and therefore they are considered to be the same as the predictions of the appropriate economic theory. Expectations are formed differently and depend on the economics system and the theory that is applied to describe the economy at a particular period. In view of the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis the economic expectations theory became more appropriate. However, an alternative theory of bounded rationality places focus on limitations in personal decision making. According to the expectations theory an illusion about a positive or negative economic growth can actually influence real growth, as people can have propensity to spend or save money. In this case savings shall be viewed as a significant determinant of economic growth. Individuals make forecasts about future economic development on the basis of personal expectations and anticipate particular policy implications (Cate, 2013).

The adaptive expectations theory suggests that the decisions and expectations are based on the past events, so these events can influence the future. Specifically, the growth of subsequent year is expected to be consistent with the growth in the past years. The changes in the conditions imply that the expectations change as well. Nevertheless, there is a time lag before the change in the expectations as a response to the changes in the conditions. The adaptive expectations theory can be expressed as follows:

(1)

Where λ takes the value between 0 and 1, gε is the growth in the next year according to the

23 and g is the actual growth rate. The equation demonstrates the relationships between the actual growth and expected growth rates. Higher expectations in the current period that were observed in the previous period, imply higher expectations in terms of the next year growth. Higher actual growth is associated with higher expectations for future growth as well.

In contrast to the adaptive expectations theory, the rational expectations hypothesis suggests that the decisions and expectations are based on all available information, including the possible policy changes and their effects on the economy. The rational expectations approach states that instead of assuming that the future will consistently reflect the past, people may take into account the possible effects of policy changes. The expectations may alter in accordance with the understanding of the economic policy. Thereby, the approach assumes that as economic agents obtain more information about the process, they use this information to form expectations of the variable that is determined by this process. Thus, the agents’ subjective probability distribution is in line with the objective probability distribution of the events. This implies that the agents’ expectations are the same as the conditional mathematical expectations according to the probability model of the economy. The value of variable Y for the period t can be determined by its lagged value and the lagged values of other variables:

(2)

Where α are the constant coefficients. A rational person who forms the expectations about the value of Y takes into consideration the equation and forms the following expectation:

(3)

Where Et-1 is the expectation of Yt that was formed in accordance with the available information

24 mathematical expectation of Yt taking into account the information available. The probability

model introduces a random term vt into the equation:

(4)

Meanwhile, the forecaster forms the expectations in regards to v as well, so the equation is the following:

(5)

Where Et-1vtis the expectation of vt that was formed according to the information available at the

end of the period t-1. The best guess that a rational agent can make with respect to vt is that it

will equal its mean value Et-1vt=0. Therefore, the rational expectation of Yt according to the

available information at the end of period t-1 can be expressed by equation (3).

2.2. Empirical Evidence

2.2.1. Economic Growth and Trade

The relation between openness to trade and economic growth can be not straightforward, as growth can use a large number of openness measures. Specifically, trade intensity ratios can be applied to analyse the effects of trade liberalisation on economic development. However, the application of trade barriers as the proxy for trade openness is possible as well. The observations of Yanikkaya (2003) showed that in contrast to expectations, both trade intensity ratios and trade barriers were positively and significantly associated with economic growth. The findings were especially strong for developing economies. The analysis of a wider range of trade openness and

25 liberalisation indicators was conducted by Wacziarg and Welch (2008). The authors explored the relation between trade openness and economic growth, including the factor of physical capital investment. The study showed that during the period from 1950 to 1998 countries that liberalised their trade regimes had an average annual growth that was 1,5 percentage points higher than prior to liberalisation. Therefore, the study concluded that liberalisation was able to promote economic growth through its impact on physical capital accumulation. The average trade to GDP ratio was increased by 5 percentage points. Nevertheless, there were large cross-country differences that were masked by average numbers (Wacziarg and Welch, 2008).

The link between trade and growth can be explored with the help of diffusion-based models that suggest that trade with integrated partners ensure greater access to technical knowledge. In contrast, structure-based models suggest that trading with isolated partners can ensure a bargaining advantage (Clark and Mahutga, 2013). Empirical analysis of a sample of over 100 countries analysed the influence of trade centrality on economic development net of control variables. The study found that there were positive relations between trade centrality and growth peaks when countries traded with isolated partners in the periphery. Cross-country differences of the effects of trade openness on economic growth can be attributed to economic conditions when trade liberalisation reforms are undertaken (Falvey, 2012). Trade liberalisation is able to increase economic growth both in crisis and non-crisis periods. However, an internal crisis is associated with lower acceleration of growth, while an external crisis implies a higher acceleration in comparison to the non-crisis regime.

A country’s economic growth along with the rate of innovation can be determined by high-technology trade and FDI (Schneider, 2005). A panel data set of over 45 developed and developing countries showed that high-technology imports were able to explain domestic

26 innovation in both developing and developed economies. Foreign technology was stronger related to GDP per capita than domestic technology. However, the findings about the effects of FDI on economic development were mixed (Schneider, 2005). In contrast, the observations of Eris and Ulasan (2013) showed that there was no direct and robust correlation between trade openness and economic growth in the long run. Different proxies for trade openness, including current openness, real openness, the fraction of open years and the weighted averages of tariff rates, as well as the black market premium were applied. The findings were robust for the inclusion of the proxies as none of them was related to economic growth. Meanwhile, the study concluded that economic institutions and macroeconomic uncertainties, including those created by high inflation and high level of government consumption were the most prominent explanatory factors of economic growth.

The positive relations between trade openness and economic growth were found by Shahbaz (2012). The author confirmed co-integration among the series using different econometric approaches. However, contrasting conclusions were provided by the research of Tekin (2012). The author explored causal relations between trade openness and economic growth and found that there was no significant causality relation among the variables. However, the study was focused only on the least developed countries of Africa, while the conclusions for the developed countries could be different. Developing countries can demonstrate a link between financial development and trade. Financial intermediaries can facilitate large-scale high-return projects, while economies with higher level of financial sector development have a comparative advantage in manufacturing industries (Beck, 2002). Controlling for country-specific effects and possible reverse causality, empirical evidence demonstrated that financial development significantly

27 affected the level of both exports and the trade balance of manufactured goods. These factors could further affect economic growth (Beck, 2002).

An example of European trade liberalisation and export-led growth was explored by Balaguer and Cantavella-Jorda (2004), who studied the economic growth in Spain. The authors took into account the expansion of export and the shift from conventional exports to other types of exports, such as manufactured and semi-manufactured ones. The study confirmed that the structural transformation in export composition was a prominent factor in the economic growth of Spain along with the relations between total exports and output (Balaguer and Cantavella-Jorda, 2004). However, the effects that trade openness has on economic growth can be determined by corresponding reforms that assist a country in benefiting from international competition. According to the Harris-Todaro model the benefits through openness to trade are determined by the level of labour market flexibility. Evidence on the impact of openness on growth with regard to various structural characteristics was provided by the research of Chang et al. (2009) in a cross-country analysis. A regression model was used and measured that trade openness interacted with the variables of financial depth, infrastructure, the flexibility of labour market, educational investment, ease of entry and exit for companies and inflation stabilisation. The study showed that the impact of trade openness on growth was substantially enhanced under particular complementary reforms (Chang et al., 2009).

Another analysis of a South European country with regard to the relations between the concepts of exports, imports and economic growth was undertaken by Ramos (2001). The study explored the Granger-causality between the factors in Portugal. The role of imports in the causality between exports and output was emphasised, thus enabling different forms of causality between output growth and export growth. The findings did not demonstrate that the variables had any

28 unidirectional causality. A feedback effect was observed between such variables as exports-related growth and imports-exports-related growth. Furthermore, import-export growths demonstrated no causality. Therefore, the study confirmed that the growth of output in the economy of Portugal had the features of a small dual economy where the intra-industry trade was of limited effect on the growth of the country. In contrast, the evidence from Italy demonstrated that the country’s growth was export-led. The tests of the macroeconomic variables, including a GDP index of the countries across the globe, the real exchange rate in Italy, real exports of Italy and the real GDP in Italy were conducted by Federici and Marconi (2002). The authors confirmed the export-led growth hypothesis of the country.

Export growth is often considered to be one of the major factors that assist in economic recovery (Griffith and Czinkota, 2012). However, the analysis of export lenders demonstrated that changes in the structure of the financial sector and economic recession may lead to the policy that mitigated the positive effects of exports on economic recovery. Furthermore, the findings showed that current investment policies often were concentrated on short-term returns instead of favouring a long-period market strategic position of the exporter. Lender preferences along with governmental rules that increased regulation of the financial industry significantly constrained economic recovery. Therefore, key lender and governmental rule amendments could mitigate the constraints in the industry and release the export accelerator that assists in economic recovery (Griffith and Czinkota, 2012). On the other hand, economic growth through internationalisation shall not be viewed purely as an export-led outward phenomenon. Companies contribute to economic development by becoming internationalised through shifting to import-led activities. Furthermore, inward and outward trade activities and investments are often closely related to each other (Fletcher, 2001). Empirical evidence showed that a majority of companies were

29 involved in inward, linked and outward international activities. The factors that predicted outward internationalisation were also able to predict inward and linked internationalisation (Fletcher, 2001).

2.2.2. Economic Growth and FDI

Trade openness and economic growth link is often explored in combination with FDI effects (Belloumi, 2014). The findings of the study showed that there was no causality from FDI to economic development, from economic growth to FDI, from trade to economic growth and from economic growth to trade in the short term. While the assumption was that FDI could generate positive spill-over effects to the host economy, the findings of a single country study were not consistent with the assumption. Therefore, it was concluded that the positive influence of FDI and trade liberalisation on economic growth was not inherent to all countries and considerable cross-country differences could exist (Belloumi, 2014). The research of Christiaans (2008) provided partial explanation for the possible differences among countries. The author explored the relations between international trade, growth and industrialisation. The study assumed a positive impact of population growth on per capita income growth. However, the assumption was alleviated by allowing for international trade. The author demonstrated that when the rate of population growth was large and the initial capital stock was small, the growth-trade linkage reversed from positive to negative. The time of the shift from autarky to free trade influenced the process of industrialisation. Trade policy affected structural change and long-term growth rates.

FDI can significantly influence economic growth through different channels. For example, the efficiency channel can be one of such ways through which FDI contribute to economic development. An analysis of European countries that was undertaken by Eller et al. (2006) showed that there was a hump-shaped influence of the FDI in the financial industry on economic

30 development. Medium FDI contributed to growth provided that human capital was sufficient. Above a certain threshold a crowding-out effect of local physical capital through the entry of overseas banks slowed down. The authors combined the FDI-related and the finance-related approaches to growth and demonstrated that the level and quality of FDI affected the contribution of the financial sector to economic development. However, the study was concentrated on emerging European markets (Eller et al., 2006). In contrast, the observations of Hermes and Lensink (2003) found that the level of development of the system of finance in the host economy was a significant predictor of the degree of FDI effects on economic growth. Higher degree of financial system development facilitated technological diffusion that was related to FDI. Empirical investigation of the role of the level of development of the system of finance in improving positive relations between the proxies of FDI and economic growth on a sample of over 65 countries was conducted. The study concluded that in order to ensure that FDI had positive influence on economic growth, the financial system needed to be sufficiently developed (Hermes and Lensink, 2003).

FDI, financial market and economic growth can have various links (Alfaro et al., 2004). Particularly, it was argued that countries with more developed financial systems could make use of FDI with higher efficiency. Cross-country data demonstrated that FDI alone was not able to demonstrate a sufficient impact on economic development. Nevertheless, countries that were characterised by higher degree of financial markets’ development could gain substantially from FDI. The findings were robust to different proxies of the level of development in financial markets, the supplementation of the model with other factors that could determine economic growth and consideration of endogeneity (Alfaro et al., 2004). Meanwhile, the analysis of Choe (2003) that was based on a sample of 80 countries showed that FDI Granger-caused economic

31 development and vice versa. Nevertheless, the effects were stronger from growth to FDI than from FDI to growth. Besides, the study found that gross domestic investment did not demonstrate causal relations with economic growth, while economic development Granger-caused gross domestic investment. Furthermore, the findings demonstrated that strong positive relations between economic development and the inflows of FDI did not imply that high level of inward FDI contributed to rapid economic growth (Choe, 2003).

The influence of FDI on economic growth can be both direct and indirect. The study of Li (2005) showed that FDI not only directly promoted economic development, but also indirectly affected growth through interaction terms. The investigation took into consideration a panel data for over 80 countries and was based both on single equation and simultaneous equation methods. The interaction of FDI with human capital was responsible for the positive impact of FDI on economic growth, while the relations between FDI and the technology gap had a strong negative effect (Li, 2005). However, there can be other determinants of the degree of contribution of FDI to economic development. Wijeweeraet al. (2010) estimated the relations between FDI and GDP growth with the application of a “stochastic frontier model”. The authors employed panel data that covered over 45 countries for the period from 1997 to 2004. The study showed that a positive influence of FDI on economic growth was possible only when highly skilled labour was at place. At the same time, corruption negatively affected economic growth, while trade openness contributed to economic growth through efficiency gains.

The effects of FDI can vary significantly across sectors (Alfaro, 2003). Specifically, the effect of FDI on growth in the primary, manufacturing and service sectors can be different. An empirical cross-country analysis demonstrated that total FDI had an ambiguous effect on growth. Nevertheless, FDI in the primary sector negatively affected growth, while FDI in manufacturing

32 had a positive effect. Evidence from the service sector was mixed. FDI can influence economic growth indirectly and exert positive effects on firms’ productivity growth instead. An analysis of the UK manufacturing sector showed that spill-overs led to a positive correlation between total factor productivity of a domestic plant and the foreign-affiliate share of activity in the industry of that plant (Haskel et al., 2007).

The contributions of horizontal and vertical FDI can have different degree of impact on economic growth in developed countries (Beugelsdijk et al., 2008). Horizontal, or market seeking FDI, had a superior growth effect over vertical, or efficiency seeking FDI. The analysis of 44 host countries and the application of traditional total FDI statistics as a benchmark showed that there was no significant effect of horizontal or vertical FDI in developing countries (Beugelsdijk et al., 2008). Meanwhile, the research of Azman-Saini et al. (2010) demonstrated that FDI did not have any direct positive impact on output growth in a panel of 85 countries. Instead, the authors found that the effect was determined by the degree of economic freedom in the host economies. Therefore, countries that ensured higher level of freedom of economic activities were able to gain substantially from the presence of multinational corporations and FDI (Azman-Saini et al., 2010).

33

2.2.3. Economic Growth and Bioenergy

“Bioenergy contributes to many important elements of a country’s or region’s development including: economic growth through business expansion and employment; import substitution; and diversification and security of energy supply. Other benefits include support of traditional industries, rural diversification, rural depopulation mitigation and community empowerment”.

International Energy Agency (IEA, 2003 p.5)

Biofuels initially presented themselves in the transportation sector as early as with the Henry Ford’s famous Model T that was capable of running with both conventional petrol and ethanol. Apart from the energy crisis of the 1970s, when there was an increase in bioenergy production, the low petrol prices until the beginning of the new the 21st century delayed the development of

biofuels. With the current environmental and socio-economical aspects governed by the energy supplies, biofuels re-entered the scene when the price of a barrel of crude oil reached 25 USD. Bioenergy currently constitutes a small percentage of the energy supply around the globe, steadily growing in the past two decades, while it is expected to intensify due to the high fossil fuel prices and the environmental benefits that bioenergy presents. Such environmental benefits can be summarised, but not limited to: renewability, as the fossil fuel availability diminishes; cleaner burn, resulting to fewer and less harmful emissions of acid rain precursors and greenhouse gases that cause climate change; and also biodegradability, as a biofuel associated accident will not produce an environmental danger of lead and sulphur spill. The development of the bioenergy sector offers a significant opportunity to address the challenging targets on renewable energy, emission reductions and waste management, as they will be presented below in the European Commission’s directives paragraph.

34

Categorising bioenergy

There are various types of bioenergy, or, more specifically, biofuels available today to economies. These include biobutanol, bioethanol, biomethanol, biogas, pyrolysis oils and biohydrogen. Among those biofuels that can potentially substitute traditional gas, it is valid to distinguish bioethanol and biodiesel that can both be transported in liquid form and used instead of gasoline.

As briefly mentioned in the introduction of this dissertation, biofuels are categorised in two generations: the first - also called conventional - being those deriving from food sources, such as sugar, starch, cereals and vegetable oil and the second - also called advanced - produced from sustainable feedstock of lignocellulosic biomass that is no longer useful as food source, such as municipal and industrial waste, animal manure, wine lees, switchgrass, jatropha tree etc. A third generation is the production of biodiesel from algae. The fourth generation refers to engineered crops of higher carbon storage capacity with higher biomass yields and the use of a series of physical and chemical processes for separation of H2/CH4/CO from CO2 to produce ultra clean carbon-negative fuels. A variety of production methods are used for the utilisation of biomass towards the generation of bioenergy, as presented in the figure below.

35

Figure 1: Methods of producing biofuels from biomass. (Festel, 2008)

Biomass has the second largest percentage3 of renewable electricity generation in the EU-27.

Sweden and Finland hold the biggest shares, while recently RES-E4 generation from biomass

increased in Denmark, Italy and the United Kingdom. Further increase of cumulative biomass capacity is expected due to large potentials in the new EU Member States (EmployRES, 2009), as presented in the figure below.

3 The wind capacity of on-shore facilities holds the highest percentage (Employ RES, 2009). 4 RES-E refers to the share of Renewable Energy Resource used for Electricity.

36

Figure 2: Historical development of cumulative installed biomass capacity in EU27 countries (Eurostat, 2014)

The debate on bioenergy and economics of biofuels

However, the production of the biofuels was also associated with particular challenges and debates in the economies. These included the debate on the environmental impacts of the first generation bioenergy that was produced using food crops. The debate concerned the trade off between food and energy and also covered the possible negative impacts of the first generation bioenergy on the environment. Given these arguments, the previous studies report that there are a limited potential for the future use of the first generation bioenergy and it is unlikely to become a serious alternative to the traditional fuels (Eisentraut, 2010). This critical attitude towards the first generation bioenergy prompted the countries to creatively investigate the production of the second generation biofuels. The latter have some advantages over the first generation bioenergy as the wastes are reduced and there is a lesser negative impact on the environment (Eisentraut, 2010).

37 Thus, the second generation bioenergy can play a significant role in the future economies and have a strong effect on the economic growth and development. However, in terms of land economy, there is a competition between the production of the second generation biofuels that have positive economic effects in the Eurozone and food production. This competition for the land may cause the second generation bioenergy to become unsustainable and a weak alternative to the traditional fuels (Carriquiry et al., 2011). An alteration of land allocation will lead to a shift of labour allocation as well with mobility between sectors and regions. In order to increase sustainability of bioenergy, Eisentraut (2010) suggests that newer technologies should be researched and the land use should be optimised for the production of bioenergy, with research and development towards the identification of more efficient pathways of bioenergy production from sustainable sources being in the centre of attention of policy makers. Another issue associated with the use of the biofuels and particularly the second generation bioenergy is the cost of production. According to the estimates of Carriquiry et al. (2011), the current costs of the production of bioenergy exceed the cost of diesel fuel by as much as seven times. It is also argued by Carriquiry et al. (2011) that fiscal incentives could help enhance the economic attractiveness of the alternative biofuels. It is generally accepted that if significant reduction of gas emissions is achieved through the use of the second generation biofuel technologies, they could crowd out traditional energy sources and make the Eurozone more independent and secure in terms of energy supplies. This autarky and stability would be expected to have a positive effect on the economic growth. The bioenergy technologies, currently in experimental status, have a strong potential in being environmentally sustainable. As predicted by Raneses et al. (1999), the alternative bioenergy is expected to find the largest room in the sphere of the marine industry, transportation and mining. In regards to significance of the potential effect of the

38 production of alternative bioenergy on the economic growth, there is no consistent position in the literature and the findings are usually mixed. Kretschmer et al. (2009) argue that the outcome will depend on the changes in technologies and regulations. They assert that both negative and positive effects on the economy could be exercised by the production of the alternative biofuels. The economic impact of one of the most popular biofuels, biodiesel for example, depends on the processes that are employed to make the fuel. The alkali-catalysed process, which uses the vegetable oil, is estimated to be one of the least costly in the production of bioenergy. However, the acid-catalysed process, which employs the waste cooking oil, is believed to be more economical since it incurs even lower production costs which allows for setting a lower price for the final refined product and yield higher returns (Zhang et al., 2003).

The cost of production is not the only factor that countries consider in choosing the alternative bioenergy instead of the traditional fuels. There are other characteristics such as how much energy can be produced by burning biofuels in comparison to the traditional fuels and the respective effects on the environment and ecology. Even with the technologies available in 2006, the production of the bioenergy is not expected to trigger a shortage in the supply of food crops for non-fuel purposes (Hill et al., 2006). It is also underlined that the greenhouse gas emissions are considerably lower when burning biodiesel than traditional fossil fuels (Hill et al., 2006). Another advantage of biodiesel in comparison to other alternative energy sources is that it requires a smaller input of food crops to produce energy. Yet, even in this case, the opportunity cost of production biodiesel associated to the lower supply of agricultural productions for food purposes. Hill et al. (2006) estimated, based on predicted demands, that even if all food crops such as soybeans and corn were employed solely for the production of biofuels rather than used as food, this supply of bioenergy would still be sufficient only to meet approximately 12% of the

39 total demand for gasoline. However technological upgrades, alternative sources and novel protocols for the production of bioenergy are expected to work in favour of the wider usage of biofuels to cover global fuel demand.

The effect of bioenergy on economic growth

There are significant economic benefits that could be delivered as a result of the promotion and development of bioenergy in the EU. From the perspective of a policy maker, the problem associated with - or addressed by - bioenergy is finding the optimum way of allocating public resources to achieve reduction of oil imports, GHG reduction, restructuring of agriculture policy, creation of rural jobs etc. Considering the Eurozone’s performance regarding the bioenergy as an aggregate response on pollution taxes and trade regulations, a clear estimation of the response of the entire sector to a policy is difficult to be calculated, due to the complexity of the relationship of those involved: farmers, process engineers, consumers and policy makers.

Regarding the effect of biofuels on the economic growth, Demirbas (2009) argues that besides the cost of production and energy security, another factor to be considered is the creation of new jobs in the sector, adding to investments and contributing to infrastructure. Energy security as well as the aforementioned environmental factors of the global change of the climate can trigger even further changes in the energy policy of the countries of Eurozone. Furthermore the development of alternative biofuels will depend on the level of the spending on research and development, new technologies and policy regimes. Newer technologies can reduce costs of the alternative bioenergy making this type of fuels even more attractive to countries. Traditional fuels such as gas and oil impose serious risks such as environmental impacts through global climate change, volatility or uncertainty of prices of fuels, scarcity of resources and

40 concentration. The use of the biofuels can reduce such risks for the countries and this could be reflected in the positive effects on the economic growth in the long run (Gunatilake et al., 2014). Reddy et al. (2008) argue that the main drivers of the growth of the production of alternative biofuels is the worldwide increases in the oil prices and geo-political issues (Reddy et al., 2008). Both emerging and advanced economies pay much attention to the regulations that encourage the production of the first and second generation biofuels. These regulations create a favourable foundation for public and private investments in the technology related to the bioenergy and the respective research and development. Reddy et al. (2008) also evidenced a significant positive effect of the production of bioenergy on the development and growth of the agricultural sector. Thus, there are also positive economic effects of the implementation of the first and second generation biofuels in additional to the traditional sources of energy (Asif and Muneer, 2007). In conclusion to the section on bioenergy and biofuels, it is valid to note that while these alternative sources of energy have a potential to provide greater energy security and even reduce total costs of production, they also have issues that can trigger negative effects on the economy. For example, an increase in the production of the biofuels can cause a food crisis that would result in the decline of the agricultural industry and negative repercussions for the whole economy (Demirbas, 2008; Rosegrant, 2008). Yet, on the positive side, the production of biofuels reduces the risks associated with the employment of traditional fossil fuels thus helping the countries to enhance economic growth.

An economic investigation of the impacts of biofuels requires an approach of the impact on the local input demand and another on the global energy supply, both approaches complimenting each other. Since the effect of bioenergy in the economic growth of the Eurozone will be discussed in the following chapters, effects on small scale will be masked. A series of economic

41 questions arise at each of the stages of bioenergy production: biomass feedstock production through cultivation; feedstock conversion to energy; distribution of end product fuels; and respective bioenergy consumption.

Eurozone’s timeline on bioenergy

The importance of renewable energy (Figure 4) and more specifically bioenergy in the Eurozone is, for the reasons discussed above, high. Bioenergy use may shape land-use policies, as their production competes with other agricultural activities for land and labour that are both finite, while also their promotion and economical and technological feedback action may affect the supply of conventional fuels, resetting the power balance between fossil fuel producing countries, versus these producing bioenergy.

Since 2001, when in the “Communication on alternative fuels for road transport” the European Commission identified biofuels as potential future transport fuel, bioenergy has been in the focus of the agenda. In 2003 the EU adopted the Biofuels Directive (2003/30 EC), targeting at 2% of bioenergy usage in 2005 and 5,75% in 2010 and also in 2003 the energy taxation directive (2003/96 EC) allowed de-taxation of biofuels. In 2005 the Commission presented the “Biomass Action Plan” and a year later the “EU strategy for biofuels”, that served as a revision of the 2003/30 EC directive, while in 2007 the “Road Map for Renewable Energy in Europe” was published the constant increase in bioenergy production (Figure 3) in the EU27 that lead to intensification of the planning. The European Commission’s “Common Energy From Renewable Sources Targets” were established in the Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources and amended and subsequently repealed the previous 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC directives.

42 global agreement is achieved, as scheduled in the post Kyoto era; an increase of 20% in energy efficiency and a 20% of energy needs coverage by renewable energy resources. Regarding the renewable resources, it refers to 10% of renewable in transportation and at least a 14% of biofuels in the total energy usage of 2020.

Figure 3: Total EU27 biodiesel production for 2010 was over 9.5 million metric tons, an increase of 5.5% from the 2009 figures. (EBB, 2014) Figure 4: Share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption of 2005 (left) and 2012 (right) presented as a percentage on the heat map. (Ragwitz, 2006)

43

Policy Implications

For the targets set in the Horizon 2020 to be met, biofuel production should be promoted from policy makers, as will have long term positive effects on environmental factors as well as the economic growth, as discussed in this thesis. Along with the intervention designed in the European Biofuels Technology Platform of “Horizon 2020”, a policy harmonisation needs to be considered. Climate change is strongly highlighted in the political agenda in an international framework and since biofuels offer a large potential of replacing petroleum fuels, while in parallel decreasing GHG emissions and providing local and regional benefits, such as energy security and rural development, their promotion should be considered.

Regarding the future of bioenergy in Europe, in the sectors of electricity, the realisable midterm potentials up to 2020 are not expected to increase for the 2030 goals, as a saturation of the bioenergy growth will become apparent due to limitations of domestic resources and the presumed limitation of alternative imports from abroad, as presented in the figure below.

Figure 5: Total realizable potentials (2030) and achieved potential for renewable energy sources for electricity generation (RES‐E) in EU‐27 countries on technology level. (Ragwitz, 2006)

44 At the current R&D state, there is a dependence of bioenergy on government support to compete with fossil fuels at the marketplace. An overview of the complex web of international energy policies is given in the Policy Research Working Paper 4341 (Rajagopal et al., 2007), in excising tax credit for biofuels, renewable fuel standards and mandatory blending, carbon footprint tax, ethanol vehicles, as well as farm and trade policies and governmental funding for R&D.

Related to agriculture is the relationship between biofuels and international trade. A major motivation for biofuel is that they will raise farm income, which will have attendant political and economic benefits. But such gains may not be realized when domestic production competes with imports that are cheaper. This is the reason biofuel crops like other agricultural goods are also subject to barriers in the form of duties, quotas, and bans on imports. The rationale for such protection could be environmental regulations, as well as the need to support domestic farmers; enabling the development of a domestic infant industry and keeping food prices low. An obvious effect of trade barriers is to prevent the best biofuel from entering the market. In this case, tariffs should be imposed on the economically and environmentally superior biofuel, in a way that by reducing the volume of trade, welfare could actually be enhanced. One instance where this can be true is when biofuel production has environmental externalities that are not taken into account. Biofuels will also affect trade by reducing food surpluses in developed countries, which will reduce both food exports and food aid. This will allow farmers in poor importing countries to receive higher prices, which can be an opportunity to increase productivity, especially in those countries.

45

2.2.4. Other Determinants of Economic Growth

Internationalisation can have indirect effects on economic growth not only through FDI, export and import, but also through other channels, including knowledge output, structural change and competition (Mayer and Ottaviano, 2008). Regarding the European manufacturing firms for instance, a large fraction of 77% is engaged in at least one mode of internationalisation: exporter, importer, outsourcer, outsourcee or FDI maker (Altomonte, 2014). In another example, an analysis of the performance of Italian companies was undertaken by Giovanetti et al. (2013). The authors measured performance by the firms’ propensity to export and showed that performance was determined both by geographical and institutional features along with firm individual characteristics. The analysis of internationalised companies demonstrated that both firms and province heterogeneity shaped the estimated results. The structural changes can be a response to internationalisation. Specifically, the institutional structure of production can determine firms’ performance (Bertolini and Giovanetti, 2006).

The effects of internationalisation on knowledge output were analysed by Pittiglio et al. (2009). The authors collected qualitative information about Italian manufacturing companies and applied a probit model in the econometric analysis. The findings showed that companies that were active in international market were able to generate more knowledge than their counterparts that sold solely in the national market. The authors concluded that internationalisation led to the employment of more knowledge inputs, for example led to higher innovation expenditures. Besides, internationalisation could contribute to innovation due to better access to a larger number of ideas from outside sources (Pittiglio et al., 2009). Different factors can influence economic and innovative performance of companies. The analysis of Italian manufacturing firms showed that exporters had moderate innovative performance between non-internationalised and

46 internationalised companies (Castellani and Zanfei, 2007). Multinational corporations with a weaker focus on foreign markets had a higher degree of productivity than exporters, but they did not innovate more than highly internationalised firms. Heterogeneity in productivity was robust to controlling for such factors as innovation outputs and inputs. This implied that the differences in economic performance were not determined by different innovative activities. The degree of internationalisation could be a strong channel of accumulation of knowledge (Castellani and Zanfei, 2007). More recent data by Altomonte et al. (2013) on European manufacturing firms, showed a positive and strong correlation between the extent of involvement of firms on both international and innovation activities. In particular, firms that export their goods and/or have set up factories abroad are, on average, also more likely to have invested into in-house research, introduced new IT solutions, or adopted new management practices. The linkage between internationalisation and innovation is bidirectional, as almost all innovating firms import and more innovative firms source more foreign products (Boler et al., 2012). Altomonte et al. (2014) constructed a measure of internationalisation intensity, defined as the number of internationalisation modes in which a firm is simultaneously involved and innovation intensity, defined as the number of innovation modes in which a firm is simultaneously involved. As the pyramidal structure of the figure below shows, innovation and internationalisation intensities are positively correlated, while the number of highly international and highly innovative firms is low. A similar pyramidal structure appears in the employment to innovation correlation, offering evidence that higher intensities are also associated with better firm performance, as measured by the employment status, that is the size of the firm.