Review Article

Quality of Life in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus:

A Systematic Review

Daniela Marchetti,

1Danilo Carrozzino,

1,2Federica Fraticelli,

3Mario Fulcheri,

1and Ester Vitacolonna

31Department of Psychological Health and Territorial Sciences, “G. d’Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy 2Psychiatric Research Unit, Psychiatric Centre North Zealand, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hillerød, Denmark 3Department of Medicine and Aging, “G. d’Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy

Correspondence should be addressed to Ester Vitacolonna; [email protected] Received 30 December 2016; Accepted 9 February 2017; Published 23 February 2017 Academic Editor: Rosa Corcoy

Copyright © 2017 Daniela Marchetti et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background and Objective. Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) could significantly increase the likelihood of health

problems concerning both potential risks for the mother, fetus, and child’s development and negative effects on maternal mental health above all in terms of a diminished Quality of Life (QoL). The current systematic review study is aimed at further contributing to an advancement of knowledge about the clinical link between GDM and QoL. Methods. According to PRISMA guidelines, PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane databases were searched for studies aimed at evaluating and/or improving levels of QoL in women diagnosed with GDM. Results. Fifteen research studies were identified and qualitatively analyzed by summarizing results according to the following two topics: GDM and QoL and interventions on QoL in patients with GDM. Studies showed that, in women with GDM, QoL is significantly worse in both the short term and long term. However, improvements on QoL can be achieved through different intervention programs by enhancing positive diabetes-related self-management behaviors. Conclusion. Future studies are strongly recommended to further examine the impact of integrative programs, including telemedicine and educational interventions, on QoL of GDM patients by promoting their illness acceptance and healthy lifestyle behaviors.

1. Introduction

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) is defined as “diabetes diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy that was not clearly overt diabetes prior to gestation” [1]. GDM is one of the most frequent metabolic diseases during pregnancy and approximately affects 7% (range: 2–18%) of all pregnancies [2–5]. This clinical condition potentially affects not only negative medical outcomes but also the mental health status with additional adverse consequences on psychological well-being and Quality of Life (QoL) [6, 7].

Pregnancy is a particular time for all women. This condi-tion becomes even more delicate when there is a diagnosis of GDM which makes necessary controls and therapies that will inevitably affect the woman’s life. GDM can lead to potential risks for the mother, fetus, and child’s development, as well as clinically relevant negative effects on maternal mental health, above all in terms of a diminished QoL [8, 9].

Health-related QoL was extensively accepted as a highly relevant outcome in different clinical trials [10]. QoL poten-tially operates as a unifying concept that comprises many domains such as general, physical, and psychological health, positive social relationships, environmental mastery, purpose in life, self-acceptance, autonomy, and personal growth fac-tors [3, 11]. However, it may act by a core mechanism of subjective appraisal of own health status [12] resulting in specific diagnostic and therapeutic implications [13]. That is, QoL dimension can explain the different individual response to a standard medical treatment leading to an incomplete recovery in terms of health perception [14].

This concept was further highlighted by the World Health Organization criteria [15], which stressed the clinical rele-vance to promote the health status by not only treating phys-ical symptoms but also instilling a positive mental state [16]. In this regard, the current systematic review study is aimed at

Volume 2017, Article ID 7058082, 12 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7058082

further contributing to an advancement of knowledge about the clinical link between GDM and QoL.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Searches. According to Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [17], a comprehensive electronic search strategy was used to identify peer-reviewed articles assess-ing QoL experienced by pregnant women diagnosed with GDM up to 19 October 2016. The following keywords were used: “gestational diabetes OR gestational hyperglycemia OR hyperglycemic pregnancy” combined using AND Boolean operator with “quality of life OR well-being”. After the initial search was performed, studies were screened for eligibility; their relevance was initially assessed using titles and abstracts and finally the full review of papers. Searching and eligibility of target responses were carried out independently by two investigators (DM and DC); any type of disagreements was resolved by consensus among these primary raters and a senior investigator (EV).

Electronic research-literature databases searched includ-ed PubMinclud-ed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane databas-es. In order to detect any missed articles during the literature search, reference lists of candidate articles were reviewed for further studies not yet identified. For each excluded study, we determined which elements of the electronic search were not addressed.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria. Papers were eligible for inclusion if

they were research reports in English language describing data on QoL domains in relation to GDM diagnosis during pregnancy. We focused on studies examining QoL in women with GDM directly or evaluating the link between QoL and well-being alternatively by specifically using measures testing QoL. Based on this inclusion criterion, we selected studies referring to QoL or well-being related to QoL by consequently excluding research reports assessing well-being through measures on negative mental health (i.e., depression, anxiety, bipolar mood, and distress) or by focusing on a med-ical definition of well-being (health status, wellness, physmed-ical health, etc.). Also studies aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of programs targeted for GDM patients providing effects on QoL were included.

We excluded peer-reviewed single-case studies, reviews, meta-analyses, letters to the editor and commentaries, con-ference abstracts, books, and papers that were clearly irrel-evant. In order to generate conclusions specific to GDM, we excluded research reports aimed at addressing levels of QoL in diabetic patients, without reporting specific data for GDM subgroup (e.g., considering diabetic pregnant women those with preexisting diabetes and those receiving the first diagnosis of GDM during pregnancy). No limit was set with regard to publication date.

2.3. Analysis and Data Synthesis. The heterogeneous nature

of the identified studies (in terms of design and measures) did not permit a formal meta-analysis. Hence, narrative synthesis

approach was judged to be the most appropriate method for the review.

Studies were categorized based on the object of the study, differentiated as those that aimed at assessing association and those that evaluated interventions. Significant information for each study was summarized and compared.

3. Results

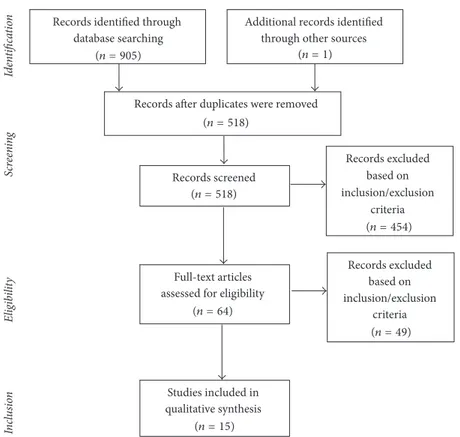

The search of PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Co-chrane databases, including additional manual search, ini-tially provided a total of 906 articles, as shown in the PRISMA flowchart (see Figure 1). Fifteen research studies were identified as clearly relevant and qualitatively analyzed in the systematic review. Pertinent results were summarized according to the following two specific chapters: (a) GDM and QoL (Table 1) and (b) interventions on QoL in patients with GDM (Table 2). Criteria for the diagnosis of GDM used in reviewed studies are illustrated in Table 3. In all but two studies [9, 26], standardized measures of QoL were used (see Tables 1 and 2 for details).

3.1. GDM and QoL. When combining an evaluation of levels

of illness acceptance with an assessment of the QoL, Bie´n et al. [3] have found that illness acceptance was significantly correlated with all QoL related scores (𝑝 < 0.05) with 𝑅 values ranging from 0.20 to 0.54. Similarly, GDM participants who did not report an individual illness interference with everyday life obtained significantly higher scores compared to those stating an illness limitation on specific QoL factors. That is, statistical differences between groups were observed on general QoL (𝑝 = 0.006), perceived general health (𝑝 = 0.006), and physical (𝑝 = 0.003), psychological (𝑝 = 0.01), and environmental (𝑝 = 0.0001) domains. Moreover, further examining QoL dimensions, the psychological domain was slightly worse than other QoL domains [3].

A similar study from Kopec et al. [19] evidenced that 171 respondents (i.e., 87.3% of the total sample specifically used for statistical analyses) reported a negative impact of GDM on their social life. Results also showed that higher levels of distress were significantly reported by women who tested glucose levels more frequently and those under treatment with insulin. In addition, patients perceiving insufficient information about their GDM symptoms reported higher levels of distress than those perceiving adequate information [19].

Another recent study from Danyliv et al. [18] compared levels of health-related QoL (HRQoL) of GDM patients with those of women with normal glucose tolerance (NGT) during pregnancy. They found significantly lower scores on HRQoL dimension for the group of GDM patients. However, when adjusting for the effects of other clinical covariates by performing a pooled multivariate analysis, the authors [18] showed that GDM per se did not influence HRQOL levels.

Similarly, a study of Dalfr`a et al. [8] compared levels of QoL between GDM patients, pregnant women with type 1 diabetes, and healthy pregnant participants. GDM respon-dents scored significantly lower than healthy controls on the SF-36 general health perception subscale (𝑝 < 0.05) as

Records identified through database searching

Additional records identified through other sources

Records after duplicates were removed

Records excluded based on inclusion/exclusion

criteria

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility

Studies included in qualitative synthesis Records screened Records excluded based on inclusion/exclusion criteria Sc re en ing E lig ibi lit y In cl u sio n Iden ti fi ca tio n (n = 49) (n = 518) (n = 15) (n = 64) (n = 454) (n = 518) (n = 1) (n = 905)

Figure 1: Flowchart of the systematic search.

evaluated during pregnancy at the third trimester. Moreover, whereas the SF-36 domains of QoL significantly improved after delivery among all three groups, rates of the SF-36 general health perception subscale remained significantly lower in GDM patients than in healthy controls [8].

Results in contrast with aforementioned findings were obtained from a previous research study aimed at evaluating impact of GDM on HRQOL after delivery. The authors [21] revealed no statistically significant differences between GDM patients and the healthy control group on the HRQOL dimensions. Similar results were previously reported also by Mautner et al. [22]. Their study underlined no clinically relevant differences between women with GDM and the healthy control group as concerns HRQoL levels.

Different results were later obtained from Trutnovsky et al. [20] who demonstrated significantly diminished levels of QoL among GDM patients. Specifically, GDM participants showed, from mid to late pregnancy, a significant reduction of physical, psychological, social, and global scores on the World Health Organization Quality of Life subscales (WHOQOL-BREF).

Results in line with above reported data were addressed by Rumbold and Crowther [24] when evidencing that women positively screened for GDM showed lower health percep-tions than those with negative screening (𝑝 < 0.05). However, these statistical differences between positive and negative screened women for GDM were not significant late in pregnancy [24].

Similar results were provided in a study from Kim et al. [23]. This research highlighted that women with a diagnosis

of GDM were significantly more prone to report poor phys-ical function and a worse self-rated health status compared to healthy pregnant women. The same result was further supported after delivery with a greater proportion of GDM pregnant women reporting a lower self-rated health status than healthy controls. In addition, self-rated health status further worsened in the third trimester among women with GDM compared to healthy pregnant women without GDM. Surprisingly, GDM clinical condition was not significantly associated with declines in any other SF-36 health status subscales in the third trimester [23].

Finally, Lapolla et al. [9] indirectly revealed a worsening level of QoL among GDM women when demonstrating that this diagnosis resulted in the development of anxiety symptoms.

3.2. Interventions on QoL in Patients with GDM. When

comparing QoL levels in GDM women attending different treatment programs (i.e., metformin alone, insulin alone, or a combination of both treatments), Latif et al. [25] showed that the negative influence on overall QoL was less with metformin compared to insulin. Nevertheless, the treatment combining metformin with insulin resulted in a greater negative impact on the QoL. Concerning the evaluation of treatment outcomes, Elnour et al. [28] observed statistically significant (𝑝 < 0.05) improvements in the HRQoL among patients attending a pharmacological care program.

A study, testing the effect of a telemedicine intervention, by Dalfr`a and colleagues [27] found a significant improve-ment of the SF-36 general health perception, energy/vitality,

T a ble 1: C ha rac ter ist ics o f inc luded st udies ass essin g th e im p ac t o f G D M o n Quali ty o f L if e. St ud y C o u n tr y/s et ti n g/y ea r St u d y design Aim 𝑁 Me as u re o f Q u al it y o f L if e Bi e ´ne ta l. [3 ] Po la n d Thr ee hosp it als 20 16 Obs er va tio nal st udy w it ho u t co n tro lg roup T o as se ss th e fa ctors affe ct ing Q o L (an d il ln ess accep ta nce) in p reg na n t w o men d iag n os ed wi th GD M. 11 4 p re gna n t w o m en wi th GD M W H OQO L -B R E F Da n yl iv et al .[ 18 ] Ire la n d F ive an te na ta lc en te rs in vo lv ed in The A tla n tic Dia b et es in P reg na nc y (D IP) ini tia ti ve 20 15 Obs er va tio nal st ud y w it h co n tro lg roup T o co m p are Q o L b et w ee n G D M an d N G T wom en 2 to 5 ye ar s aft er p reg na nc y. T o exp lo re p ar ti ci p an ts ch ar ac te ri st ics w hic h m ay infl uence their Q o L. 23 4 w o m en dia gnos ed w it h GD M d ur in g p re gna n cy 10 8 w o m en w it h a h isto ry of h ea lt h y p re gn an cy V is u al A n alog Sc ale o f th e EQ-5D-3L Ko p ec et al .[ 19 ] Po la n d Un iv er si ty -a ffi li at ed G D M cl inic 20 15 Obs er va tio nal st udy w it ho u t co n tro lg roup (lo n gi tudinal) T o ass ess, amo ng o ther o b je ct ives, fac to rs affe ct ing the Qo L o f p re gn an t w o m en wi th G D M . 205 p re gn an t w o m en dia gnos ed w it h G D M SF -8 T ru tn o vs ky et al .[ 20] Au st ri a U n iv er si ty GD M clinic 20 12 Obs er va tio nal st udy w it ho u t co n tro lg roup (p ro sp ec ti ve ) T o ev al u ate, amo ng o ther o u tco mes, Q o L o f w o m en tr ea te d fo r G D M. 45 p reg na n t w o men aff ec te d by G D M ,d iv ided ba sed o n ty p e o f tr ea tm en t: 27 diet-t re at ed w o m en 18 diet p lu s in sulin w o men W H OQO L -B R E F La p o ll a et al .[ 9] It al y T en d ia b ete s ce n te rs sp ec ia lize d in the ca re o f pre gn an t wom en 20 12 Obs er va tio nal st udy w it ho u t co n tro lg roup T o ev al u ate Q o L ,w is h es ,a n d n ee d s o f It al ian an d immigra n t w o men d ia gnos ed wi th GD M. 286 p re gn an t w o m en aff ec te d by G D M ,d iv ided in to tw o gr o u p s: 19 8 It al ian wom en 88 immigra n t w o men Q o L is o n ly indir ec tl y ev al ua te d w it h q uest io n s co ve ri n g fe elin gs an d co ncer n s re la te d to the dia gnosis o f G D M an d its tr ea tm en t Dal fr `ae ta l. [8 ] It al y T w el ve dia b et es cl inics 20 12 Obs er va tio nal st udy w it h co n tr ol gr o u p T o exa mine the im pac t o f dia b et es o n Q o L amo n g p regna n t w o men w it h d ia b et es (GD M and T1D M) co m p ar ed wi th p reg na n t w o men w it h a no rm al gl ucos e tol er anc e. 24 5 w o m en di vided in to th re e group s: 17 6 p re gn an t w o m en w it h GD M 30 p re gn an t w o m en w it h T1D M 39 he al th y con tr ol s (p re gna n t w o m en wi th nega ti ve GCT o r O GT T findin gs) SF -3 6 Ha lk o ah o et al .[ 21 ] Fin la nd Un iv er si ty h o sp it al 20 10 Obs er va tio nal st ud y w it h co n tro lg roup To ev al u at e th e eff ec ts o f G D M o n w o m en ’s Q o L aft er deli ve ry . 77 w o m en d ia gn o se d w it h GD M d ur in g p re gna n cy 54 he al th y co n tr ols (wo men wi th no rm al gl ucos e tol er anc e te st s d u ri ng pre gn an cy ) 15D H R Q oL

Ta b le 1: C o n ti n u ed . St ud y C o u n tr y/s et ti n g/y ea r St u d y design Aim 𝑁 Me as u re o f Q u al it y o f L if e Maut n er et al .[ 22 ] Au st ri a Pub lic hosp it al 2009 Obs er va tio nal st ud y w it h co n tro lg roup (lo n gi tudinal) T o explo re Q oL (a nd th e incidence o f d ep re ssive sy m p to ms ) in w om en du ri ng pre gn an cy an d aft er d el ive ry ,c om p ar ing wom en w it h G DM ,h yp er te ns iv e dis o rd er s, an d risk fo r p ret er m d eli ver y w it h a co n tr o l gr o u p cha rac ter ized by unco m p lica te d p re gna n cy . 90 p re gn an t w o m en , di vided in to fo u r gr o u p s: 18 wo men affe ct ed by h yp er ten si ve dis o rd er s 11 w o men aff ec ted by GD M 32 w o m en at ri sk o f p ret er m d eli ver y 29 he al th y co n tr o ls (p re gna n cy wi th o u t co m p lica ti o n s) W H OQO L -B R E F Ki m et al. [2 3] Cal if o rn ia ,U SA Si x h o sp it als 2005 Obs er va tio nal st ud y w it h co n tro lg roup (p ro sp ec ti ve ) T o in ve st iga te the infl uence o f G D M (a nd PIH) o n ma ter n al he al th st at us, test ing th e h yp o thesis tha t, am ong o th er s, wom en w it h G DM wou ld h av e a gr ea t lik eliho o d to re p o rt dec lines in he al th st at us th an wo men w it ho u t GD M, w it h at le ast a p ar ti al m ed ia ti o n by ces ar ea n b ir th o r p ret er m d eli ver y. 14 4 5 pre gn ant w o m en di vided in to thr ee gr o u ps: 64 w o m en w it h G D M 14 8 w om en w it h P IH 123 3 h eal th y w o m en Ph ysical fu nc ti o nin g scale , vi tali ty sc ale ,a n d se lf-ra te d h eal th it em o f th e SF -36 Ru m b o ld an d Cr o w th er [2 4] So u th A u st ra li a H o sp it al wi th a hig h-r isk p reg na nc y ser vice an d neo n at al in te n si ve ca re uni t 200 2 Obs er va tio nal st ud y w it h co n tro lg roup (p ro sp ec ti ve ) T o sur ve y p reg na n t w o men o n their exp er ience o f b ein g sc re ened fo r G D M ,t est in g th e h yp o thesis tha t w o m en wi th a G D M diag nosis w o u ld exp er ience a red uc ti o n in Q o L (p er cep ti o n o f th e p re gn an cy ,t heir he al th ,a nd th at o f th ei r b ab y) co m p ar ed wi th w o m en w it h a nega ti ve sc re enin g resul t. 14 5 p re gn an t w om en di vided in to tw o gr o u ps 21 wi th p o si ti ve O G T T (GD M gr o u p) 12 4 w it h n ega ti ve O GT T SF -3 6 GD M: G est at io na l D ia b et es M elli tu s; N G T :no rm al gl ucos e to lera n ce; O GT T :o ra l gl ucos e to lera n ce te st; Q oL: Q ua li ty o f L if e; P IH: p re gna n cy -ind uce d h yp er te n sio n; T1D M: typ e 1 d ia b et es m elli tu s; EQ-5D-3L: 3-le vel ve rsio n o f the E u ro Q o l 5-Dimen sio n ;1 5D HR Q o L: 15-Dimen sio n al H ea lt h -Rela ted Q u al it y o f L if e; SF -3 6: 36 -I te m Sho rt -F o rm H ea lt h Sur ve y; SF -8: 8-I te m Sho rt -F o rm H ea lt h Sur ve y; WH O Q O L -BREF : W o rld H ea lt h O rg an iza tio n Q ua li ty o f L if e-BREF .

T a ble 2: C ha rac ter ist ics o f inc luded st udies ass essin g th e im p ac t o f tr ea tmen ts o n Q uali ty o f L if e am o n g G D M p regna n t w o men. St ud y C o u n tr y/s et ti n g/y ea r St u d y design Aim 𝑁 Me as u re o f Q u al it y of L ife La ti f et al .[ 25 ] En gl an d T w o h o spit al s 20 13 Quasi-exp er imen tal st ud y Thr ee co ndi tio n s: (1) T re atmen t w it h met fo rmin (2) T re at men t wi th in sulin (3) T re at men t wi th met fo rmin + in sulin T o exa mine Q oL (a nd tr ea tm en t sa tisfac tio n) o f w o men aff ec te d by G D M re cei vin g met fo rmin alo n e, in sulin al on e, or a combi n at ion of b o th tr ea tm en ts . 12 8 w o m en dia gnos ed w it h GD M d ur in g p re gna n cy as sign ed to o n e o f thr ee co ndi tio n s: 6 8 tr ea te dw it hm et fo rm in 32 tr ea te d w it h in su li n 28 tr ea te d w it h m et fo rmin +i n su li n AD D Q oL Pe tk o va et al .[ 26 ] Bu lg ar ia An te na ta lc linic 20 11 Quasi-exp er imen tal st ud y Tw o co n d it io n s: (1) E d uca tio n gr o u p (i nt er ve nt io n ) (2) C o n tr o lgr o u p T o in ve st iga te the eff ec ti ve ness o f an ed uca tio nal pro gr am for pre gn an t wom en w it h G DM on th ei r Q o L (a nd o ther o u tco mes). 30 p re gn an t w o m en aff ect ed by G D M as sign ed to o n e o f tw o co ndi tio n s: 15 assigned to th e in te rv en ti o n co ndi tio n (e du ca ti on pro gr am ) 15 assigned to th e co n tr o l co ndi tio n Fi ve it em s me asur in g Q oL Dal fr `ae ta l. [2 7] It al y T w el ve dia b et es cl inics 2009 Quasi-exp er imen tal st ud y Tw o co n d it io n s: (1) T elemedicine co n di ti o n (i nt er ve nt io n ) (2) U sual ca re co ndi tio n (co n tr o l) T o ass ess th e eff ec t o f a telemedicine in ter ve n tio n o n Q o L (a n d o th er o u tc o m es) amo n g p reg na n t w o men wi th dia b et es (GD M an d T1D M). 23 5 p re gn an t w o m en di vided in to tw o gr o u ps: 20 3 w o m en wi th GD M 32 w o men w it h T1D M P ar tici p an ts o f ea ch gr o u p w er e seq u en tiall y as sign ed to o n e o f tw o co ndi tio n s: 88 w o men aff ec ted by GD M an d 17 w om en affe cte d by T1D M assig ne d to the te lemedicine co n di ti o n 115 w o m en aff ec te d by GD M and 15 wo men aff ec te d by T1D M assigned to th e co n tr o lco ndi tio n SF -3 6

Ta b le 2: C o n ti n u ed . St ud y C o u n tr y/s et ti n g/y ea r St u d y design Aim 𝑁 Me as u re o f Q u al it y of L ife E lno ur et al .[ 28 ] U n it ed Ara b Emira tes Ho sp it al 2008 Ex pe ri m en tal st udy (RC T) Tw o co ndi tio n s: (1) Pha rmaceu ti ca lc ar e pro gr am (i n te rv en ti on ) (2) U sual ca re (co n tr o l) T o ev al ua te th e eff ec t o f a p ha rm aceu ti ca lc ar e in te rv en ti on pro gr am m e for wom en w it h G DM on Q o L( an do th er o u tc o m es )b o thd u ri n gp re gn an cy an d aft er deli ve ry . 18 0 p re gn an t w o m en dia gnos ed w it h G D M ra ndo m ly assigned to o n e of tw o con d it ions : 10 8 assig ne d to the in te rv en ti o n co ndi tio n 72 as si gn ed to th e cont ro l co ndi tio n SF -3 6 Cr o w th er et al .[ 29] Ne w So u th W al es ; Quee n sla n d ;S o u th Au st ra li a; E n gl an d ; Wa le s E ig h te en an te na ta l cl inics 2005 Ex pe ri m en tal st udy (RC T) Tw o co ndi tio n s: (1) In te rv en tio n gr o u p (2) R o u tine-ca re gr o u p (co n tr o l) T o exa mine the eff ec t o f an in ter ve n tio n (inc ludin g diet ar y ad vice ,b lo o d gl ucos e m o n it o rin g ,a n d in sulin th era p y) fo r w o m en wi th GD M o n Q oL (a nd o ther p rima ry and se co nd ar y o u tco mes). 10 0 0 pre gn an t wom en w it h GD M, ra ndo m ly assigned to o n e o f tw o co ndi tio n s: 49 0 assig ne d to the in te rv en ti o n co ndi tio n 51 0a ss ig n edt ot h e co n tr o l co ndi tio n SF -3 6 GD M: G est at io na lD ia b et es M elli tu s; Q o L: Q u al it y o f L if e; T1D M: typ e 1 d ia b et es m elli tu s; AD D Q oL: A udi t o f Dia b et es-D ep enden t Q u al it y o f L if e; SF -3 6: 36 -I te m Sho rt -F o rm H ea lt h Sur ve y.

T a ble 3: D ia gnost ic cr it er ia fo r GD M o f inc luded st udies. St udy T ime and met h o d s o f d ia gn osis Di ag nost ic cr it er ia Bi e ´ne ta l. [3 ] Dia b et es fir st dia gnos ed d ur in g p re gna n cy ,i n acco rd an ce wi th th e cur re n t guidelines o f the P o lish D iab et ol o gy So ci et y: for pre gn an t wom en w it h ri sk fa ct o rs ,t h e 75 g O G T T is re q u ir ed .I f gl ycemia is no rm al ,t he te st sho u ld b e re administ er ed at 24 –2 8 w eeks o f p regna nc y o r w hen fi rs t sy m p to ms in d ic at iv e o f d ia b et es are o b se rv ed .F or wom en w it h o ut ri sk fa ct or s, th e 75 g O G T T is administ er ed at 24 –2 8 w eeks o f p regna nc y 75 -g O G T T : F P Gl ev el so f9 2– 12 5m g/ d la n d /o r 1 h PG le ve l≥ 180 m g/ dl an d/o r 2 h PG le ve l o f 15 3–1 9 9 m g/ d l D an yli v et al .[18] P reg na n t w o men w er e o ff er ed scr eenin g at 24–2 8 w eeks ’g est at io n u sin g a 75 g O G T T 75 g O GT T in acco rd an ce wi th th e IA D P SG cr it er ia Ko p ec et al .[ 19 ] GD M w as dia gnos ed by a tw o-st ep ap p roac h .Th e o ral G CT administ er ed b etw een 24 and 28 we ek s o f p re gn anc y. W ome n w it h 1 h P G le vel > 180 m g/ d l(10.0 mmo l/l) in the O G CT w er e cl assified as h av in g G D M .W o m en wi th PG le ve ls b etw een 14 0 m g/ d l( 7. 8 m mo l/l) an d 180 m g/ d l (10.0 mmo l/l) w er e ref er re d fo r a d iag n ost ic 75 g O G T T Tw o -s te p ap p ro ac h : 50 g G C T fo ll ow ed ,i f p o sit iv e, by 75 g OG T T in te rp re ti n g th e re su lt s acco rdin g to the WH O d iag n ost ic cr it er ia L at if et al .[2 5] GD M w as dia gnos ed at 28 w eeks o f p reg na nc y A 2 h 75 g O G T T acco rdin g to the W H O d ia gn o sti c cri te ria T rut n o vs ky et al .[ 20 ] D ia gn o se d G D M b as ed on th e re su lt s of an el ev at ed 75 g O G T T D ia gn o st ic cr it er ia n ot fu ll y sp ec ifi ed L ap o ll a et al .[9] G D M was d iag n os ed acco rdin g to C ar p en ter an d C o u st an ’s cr it er ia C ar p en te r and C o ust an ’s cr it er ia Dal fr `ae ta l. [8 ] Sc re enin g fo r GD M w as do ne wi th a G CT b etw een the 24 th an d 28t h w eeks o f ge st at io n, an d the diag nosis w as co nfir med w it h a 10 0 g O G T T ,i n ter p ret in g the re su lt s acco rdin g to the Reco mmenda ti o n s o f the 4t h In ter na ti o n al W o rksho p C o nf er ence o n GD M C ar p en te ra n d C o u st an ’sc ri te ri a Pe tk o va et al .[ 26 ] W o men, susp ec te d to h av e G D M ,w er e sub jec ted to 2 h 75 g G CT .Th os e w it h suga r le ve la ro und 14 0 m g/ d l( 7. 8 m m o l/ L ) o r ab o ve we re re qu es te d for O G T T re co m m en d ed by W HO Tw o -s te p ap p ro ac h : GCT + O G T T in te rp re ti n g th e resu lts acco rdin g to the WH O d iag n ost ic cr it er ia

Ta b le 3: C o n ti n u ed . St udy T ime and met h o d s o f d ia gn osis Di ag nost ic cr it er ia Ha lk o ah o et al .[ 21 ] The dia gnosis o f G D M is bas ed o n a 2 h gl ucos e to lera n ce te st ge nerall y administ er ed d u ri n g th e 24 th – 28 th w ee k s of pre gn an cy to w om en w it h G D M ri sk fa ct o rs Dia gnost ic cr it er ia no t full y sp ecified Maut n er et al .[ 22 ] The gr o u p “g est at io nal d ia b et es” inc luded w o m en dia gnos ed w it h a pa th o logical o ral gl ucos e to lera nce test req uir in g in sulin th era p y at the end o f the se co nd an d the b eginnin g o f the thir d tr imest er .The dia gnosis o f G D M is bas ed o n a pa th o logical O G T T Dia gnost ic cr it er ia no t full y sp ecified Dal fr `ae ta l. [2 7] Sc re enin g fo r GD M w as do ne wi th a G CT b etw een the 24 th an d 28t h w eeks o f ge st at io n, an d the dia gnosis w as co nfir med w it h a 10 0 O GT T C ar p en te ra n d C o u st an ’sc ri te ri a E lno ur et al .[ 28 ] W o m en wi thin th e fi rs t 20 w eeks o f ge st at io n co nfir med d ia gnosis o f GD M D ia gnost ic cr it er ia n o t sp ecified Ki m et al. [2 3] GD M w as diag nos ed acco rdin g to C ar p en ter an d C o u st an ’s cr it er ia b etw een 24–2 8 w eeks o f ge st at io n C ar p en te ra n d C o u st an ’sc ri te ri a Cr o w th er et al .[ 29] P reg na nc y b etw een 16 an d 30 w eeks ’g est at io n wi th o n e o r m o re risk fac to rs fo r gest at io n al dia b et es o n se lec ti ve scr eenin g o r a p o si ti ve 50 g G CT an d a 75 g O GT T at 24 to 34 w eeks ’ ge st at io n in acco rd an ce wi th th e W H O diag nost ic cr it er ia T w o-st ep o r o n e-st ep ap p ro ac h : 50 g G C T :1 h P G lev el ≥ 14 0 m g/ d l( 7. 8 mmo l/l) + 75 g O GT T :2 h PG le ve lo f 14 0–1 98 (7 .8–11.0 m mo l/l) o r se lec ti ve scr eenin g: 75 g O GT T in te rp re ti n g th e resu lts acco rdin g to the W H O d ia gn o sti c cri te ria Ru m b o ld an d C row th er [2 4] U n iv er sa la n te n at al sc re en in g for G D M by eit h er a ra n d om bl o o d sa m p le or a 50 g G C T at 24 to 28 w eeks ’g est at io n. W o men w ho sc re en p o si ti ve ar e o ff er ed a dia gnost ic 75 g O GT T Tw o -s te p ap p ro ac h : ra n d o m b lood sa m p le o r 50 g G C T fo ll ow ed ,i f p o sit iv e, by 75 g O G T T in te rp re ti n g th e resu lts acco rdin g to the W H O d ia gn o sti c cri te ria GCT :g lucos e cha llen ge te st; G D M :G est atio n al Dia b et es M elli tus; IAD PSG: In te rn at io na lA ss o cia tio n o fDia b et es an d P re gna n cy St ud y G ro u ps; O G T T :o ra lg lucos e to lera n ce te st; W H O :W o rld H ea lt h Or ga niza tio n.

and mental health subscales among participants attending the intervention group. Similar results were later obtained from Petkova et al. [26]. They found a significant improvement in QoL of women with GDM involved in an interven-tion program aimed at educating about diet, exercise, self-monitoring, and insulin treatment.

Finally, Crowther et al. [29] randomly assigned women with GDM to a specific intervention group aimed to provide dietary advice, blood glucose monitoring, and insulin ther-apy. At three months after delivery, participants reported a significant improvement in their QoL by obtaining higher scores on the SF-36.

4. Discussion

QoL is a clinically relevant concept determining the individ-ual evaluation of own health status. This subjective appraisal seems to act, above all physical and treatment components of diabetes during pregnancy, as a psychological factor affecting medical outcomes in GDM. Based on current research studies, we have found that QoL could be significantly compromised, both short term and long term, when women cope with pregnancy complicated by GDM. However, GDM per se does not seem to act as unique clinical variable negatively affecting different levels of QoL among women with GDM. That is, the relationship between GDM medical symptoms and QoL domains could be mediated by a complex interaction of several factors whose unifying psychological element can be identified through the concept of the ill-ness experience [30]. The potential underlying psychological factor, operating as core variable to clinically explain the different QoL status among patients with GDM, may consist of the varying individual way to respond to own bodily symp-toms. Such psychological component conceived as general health perception was originally investigated by Mechanic and Volkart [31]. In this regard, they provided a definition of “the ways in which symptoms may be differentially perceived, evaluated, and acted upon by different kinds of persons” [30]. A relatively recent review study of Lawrence [32] has further underlined how perceptions and expectations of women with GDM may significantly affect their psychological and behavioral response during and after pregnancy.

To the very best of our knowledge, this is the first review study systematically analyzing the impact of GDM and its symptoms on QoL levels. Indeed, only a previous recently published systematic review study, evaluating the health status and QoL in postpartum women, was fulfilled by Van Der Woude et al. [33]. However, the authors neglected the assessment of such psychological mechanisms in women with GDM.

Based on additional relevant results from a review study examining the influence of QoL in the treatment outcomes of diabetes [34], specific implications can be identified. The medical evaluation of GDM should comprise a clinically valid psychological assessment of QoL in order to attempt monitoring its potential effects on GDM prognosis from first diagnosis, during the treatment, and after delivery. Specifically, the gold standard should comprise self-rating scales as screening measures for identifying psychological

comorbidities potentially leading to adverse and negative clinical consequences during diabetes [35].

As regards the intervention studies examining the impact of specific treatments on QoL dimensions among women with GDM, promising results were found. The five studies retrieved [25–29] clearly indicate the efficacy of different therapeutic programs to improve QoL by enhancing positive diabetes self-management behaviors such as balanced diet, exercise, self-monitoring, and insulin control. Despite this, much more studies are largely needed when taking into account heterogeneity in subjects and study design as well as the evidence that the control group and experimental group were not consistent across studies we have qualitatively examined.

Further research should be conducted to test the effect of integrative programs on QoL focusing on pharmacological care mixed up with advanced practices based on information and communication technologies (e.g., telemedicine and/or games for health) [36, 37]. In this regard, the major aim is to educate patients on healthier lifestyle habits (healthy diet and physical activity domains) [38, 39] and to facilitate the process of illness acceptance [40] after a diagnosis of GDM.

Finally, our review shows some noteworthy points: (1) the positive effect of a telemedicine intervention on both diabetes-related medical outcomes and general health per-ception, energy/vitality, and mental health; (2) a significant improvement in QoL of women with GDM attending an educational program. In the future, these considerations should be taken into account for the management of diabetes during pregnancy.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests to disclose.

References

[1] American Diabetes Association, “2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes,” Diabetes Care, vol. 40, supplement 1, pp. S11–S24, 2017.

[2] H. Alptekin, A. C¸ izmecio¨a¨ylu, H. Is¸ik, T. Cengiz, M. Yildiz, and

M. S. Iyisoy, “Predicting gestational diabetes mellitus during the first trimester using anthropometric measurements and HOMA-IR,” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 577–583, 2016.

[3] A. Bie´n, E. Rzo´nca, A. Ka´nczugowska, and G. Iwanowicz-Palus, “Factors affecting the quality of life and the illness acceptance of pregnant women with diabetes,” International Journal of

Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 13, no. 1, article

68, 2015.

[4] B. S. Buckley, J. Harreiter, P. Damm et al., “Gestational diabetes mellitus in Europe: prevalence, current screening practice and barriers to screening. A review,” Diabetic Medicine, vol. 29, no. 7, pp. 844–854, 2012.

[5] K. Strawa-Zakoscielna, M. Lenart-Lipinska, A. Szafraniec, G. Rudzki, and B. Matyjaszek-Matuszek, “A new diagnos-tic perspective—hyperglycemia in pregnancy—as of the year, 2014,” Current Issues in Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 246–249, 2014.

[6] R. Guglani, S. Shenoy, and J. S. Sandhu, “Effect of progressive pedometer based walking intervention on quality of life and general well being among patients with type 2 diabetes,” Journal

of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, vol. 13, article 110, 2014.

[7] J. Lewko, J. Kochanowicz, W. Zarzycki, Z. Mariak, M. G´orska, and E. Krajewska-Kulak, “Poor hand function in diabetics. Its causes and effects on the quality of life,” Saudi Medical Journal, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 429–435, 2012.

[8] M. G. Dalfr`a, A. Nicolucci, T. Bisson, B. Bonsembiante, and A. Lapolla, “Quality of life in pregnancy and post-partum: a study in diabetic patients,” Quality of Life Research, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 291–298, 2012.

[9] A. Lapolla, G. Di Cianni, A. Di Benedetto et al., “Quality of life, wishes, and needs in women with gestational diabetes: Italian DAWN pregnancy study,” International Journal of

Endocrinol-ogy, vol. 2012, Article ID 784726, 6 pages, 2012.

[10] C. W. Topp, S. D. Østergaard, S. Søndergaard, and P. Bech, “The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature,”

Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, vol. 84, no. 3, pp. 167–176,

2015.

[11] C. D. Ryff, “Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia,” Psychotherapy and

Psychosomatics, vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 10–28, 2014.

[12] G. A. Fava and P. Bech, “The Concept of Euthymia,”

Psychother-apy and Psychosomatics, vol. 85, no. 1, pp. 1–5, 2016.

[13] A. Rodriguez-Urrutia, F. J. Eiroa-Orosa, A. Accarino, C. Malagelada, and F. Azpiroz, “Incongruence between clinicians’ assessment and self-reported functioning is related to psy-chopathology among patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal disorders,” Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, vol. 85, no. 4, pp. 244–245, 2016.

[14] N. Sonino and G. A. Fava, “Improving the concept of recovery in endocrine disease by consideration of psychosocial issues,”

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 97, no.

8, pp. 2614–2616, 2012.

[15] World Health Organization, Construction in Basic Documents, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 1948. [16] P. Bech, D. Carrozzino, S. F. Austin, S. B. Møller, and O.

Vassend, “Measuring euthymia within the Neuroticism Scale from the NEO Personality Inventory: a Mokken analysis of the Norwegian general population study for scalability,” Journal of

Affective Disorders, vol. 193, pp. 99–102, 2016.

[17] D. Moher, A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, and D. G. Altman, “Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement,” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, vol. 62, no. 10, pp. 1006–1012, 2009.

[18] A. Danyliv, P. Gillespie, C. O’Neill et al., “Health related quality of life two to five years after gestational diabetes mellitus: cross-sectional comparative study in the ATLANTIC DIP cohort,”

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 15, article 274, 2015.

[19] J. A. Kopec, J. Ogonowski, M. M. Rahman, and T. Miazgowski, “Patient-reported outcomes in women with gestational dia-betes: a longitudinal study,” International Journal of Behavioral

Medicine, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 206–213, 2015.

[20] G. Trutnovsky, T. Panzitt, E. Magnet, C. Stern, U. Lang, and M. Dorfer, “Gestational diabetes: women’s concerns, mood state, quality of life and treatment satisfaction,” Journal of

Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, vol. 25, no. 11, pp. 2464–2466, 2012.

[21] A. Halkoaho, M. Kavilo, A.-M. Pietil¨a, H. Huopio, H. Sintonen, and S. Heinonen, “Does gestational diabetes affect women’s health-related quality of life after delivery?” European Journal

of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, vol. 148,

no. 1, pp. 40–43, 2010.

[22] E. Mautner, E. Greimel, G. Trutnovsky, F. Daghofer, J. W. Egger, and U. Lang, “Quality of life outcomes in pregnancy and postpartum complicated by hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes, and preterm birth,” Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics

& Gynecology, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 231–237, 2009.

[23] C. Kim, P. Brawarsky, R. A. Jackson, E. Fuentes-Afflick, and J. S. Haas, “Changes in health status experienced by women with gestational diabetes and pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders,” Journal of Women’s Health, vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 729–736, 2005.

[24] A. R. Rumbold and C. A. Crowther, “Women’s experiences of being screened for gestational diabetes mellitus,” Australian and

New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 42, no.

2, pp. 131–137, 2002.

[25] L. Latif, S. Hyer, and H. Shehata, “Metformin effects on treatment satisfaction and quality of life in gestational diabetes,”

British Journal of Diabetes and Vascular Disease, vol. 13, no. 4,

pp. 178–182, 2013.

[26] V. Petkova, M. Dimitrov, and S. Geourgiev, “Pilot project for education of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) patients—can it be beneficial?” African Journal of Pharmacy and

Pharmacol-ogy, vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 1282–1286, 2011.

[27] M. G. Dalfr`a, A. Nicolucci, A. Lapolla et al., “The effect of telemedicine on outcome and quality of life in pregnant women with diabetes,” Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 238–242, 2009.

[28] A. A. Elnour, I. T. El Mugammar, T. Jaber, T. Revel, and J. C. McElnay, “Pharmaceutical care of patients with gestational diabetes mellitus,” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 131–140, 2008.

[29] C. A. Crowther, J. E. Hiller, J. R. Moss, A. J. McPhee, W. S. Jeffries, and J. S. Robinson, “Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes,” New England Journal

of Medicine, vol. 352, no. 24, pp. 2477–2486, 2005.

[30] L. Sirri, G. A. Fava, and N. Sonino, “The unifying concept of illness behavior,” Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, vol. 82, no. 2, pp. 74–81, 2013.

[31] D. Mechanic and E. H. Volkart, “Illness behavior and medical diagnoses,” Journal of Health and Human Behavior, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 86–94, 1960.

[32] J. M. Lawrence, “Women with diabetes in pregnancy: different perceptions and expectations,” Best Practice and Research:

Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 15–24,

2011.

[33] D. A. A. Van Der Woude, J. M. A. Pijnenborg, and J. De Vries, “Health status and quality of life in postpartum women: a systematic review of associated factors,” European Journal of

Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, vol. 185, pp. 45–

52, 2015.

[34] L. D. F. Gusmai, T. D. S. Novato, and L. D. S. Nogueira, “The influence of quality of life in treatment adherence of diabetic patients: a systematic review,” Revista da Escola de Enfermagem

da USP, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 839–846, 2015.

[35] C. Conti, D. Carrozzino, C. Patierno, E. Vitacolonna, and M. Fulcheri, “The clinical link between type D personality and diabetes,” Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 7, article no. 113, 2016. [36] T. M. Rasekaba, J. Furler, I. Blackberry, M. Tacey, K. Gray, and K.

Lim, “Telemedicine interventions for gestational diabetes mel-litus: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Diabetes Research

[37] Y. L. Theng, J. W. Y. Lee, P. V. Patinadan, and S. S. B. Foo, “The use of videogames, gamification, and virtual environments in the self-management of diabetes: a systematic review of evidence,” Games for Health Journal, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 352–361, 2015.

[38] D. Marchetti, F. Fraticelli, F. Polcini et al., “Preventing adoles-cents’ diabesity: design, development, and first evaluation of “Gustavo in Gnam’s Planet”,” Games for Health Journal, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 344–351, 2015.

[39] M. Tabak, M. Dekker-van Weering, H. van Dijk, and M. Vollenbroek-Hutten, “Promoting daily physical activity by means of mobile gaming: a review of the state of the art,” Games

for Health Journal, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 460–469, 2015.

[40] N. C. Chilelli, M. G. Dalfr`a, and A. Lapolla, “The emerging role of telemedicine in managing glycemic control and psy-chobehavioral aspects of pregnancy complicated by diabetes,”

International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications, vol. 2014,

Submit your manuscripts at

https://www.hindawi.com

Stem Cells

International

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

INFLAMMATION

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Behavioural

Neurology

Endocrinology

International Journal ofHindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014 Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Disease Markers

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

BioMed

Research International

Oncology

Journal ofHindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014 Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

PPAR Research

The Scientific

World Journal

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Immunology Research

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Journal of

Obesity

Journal ofHindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014 Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine

Ophthalmology

Journal ofHindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Diabetes Research

Journal ofHindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Research and Treatment

AIDS

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Gastroenterology Research and Practice

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014