Università di Pisa

Tesi Di Dottorato in Neurobiologia e Clinica dei Disturbi Affettivi (S4)

“Gender differences in heroin dependence”

Relatore Candidato

Prof. L. dell’Osso Dott. A.Romano

Co-Relatore

Dott. I. Maremmani

INDEX 1. Summary p.1 2. Introduction p.3 3. Gender Differences a. Somatic Pathology p.4 b. Psychiatric Pathology p.6 c. Social Situation p.11

d. Past History of Substance Abuse p.15

e. Proximal History of Substance Abuse p.17 f. Longitudinal History of Substance Abuse p.18

4. Aim of research p.21 5. Material e Method p.21 6. Results p.25 7. Discussion p.31 8. Conclusion p.37 9. Bibliografy p.39 10. Tables

SUMMARY

This study attempts to analyse potential gender differences among a group of heroin addicts seeking treatment at a university-based medical center.

The central modality of treatment at this centre is the use of methadone maintenance.

Using the Self-Report Symptom Inventory (SCL-90), we studied the psychopathological dimensions of 1,055 patients with heroin addiction (884 males and 171 females) aged between 16 and 59 years at the beginning of treatment, and their relationship to age, sex and duration of dependence.

Also we analyse demographic characteristics of 368 heroin addicts at first treatment according to gender.

Among those patients entering this program there seems to be an emerging pattern of males who tend to use heroin as their opiate of choice, and are more likely to combine it with cannabis, while females are more likely to use to street

methadone, with adjunctive use of ketamine,

benzodiazepines, hypnotic drugs and/or amphetamines.

Women are at higher risk of abusing opioids through a pathway of initial prescription painkiller use, and later to resort to street methadone to cope with prescription pain killer addiction. This latter pattern seems to result in an increased risk for fatal accidental overdoses. The use of these longer-acting agents in women may be influenced by psychosocial and hormonal factors.

INTRODUCTION

Studies of heroin dependent persons have described a chronic disorder strongly associated with polydrug use, poor mental and physical health, an increased risk for mortality, and poor legal, social and economic outcomes (80, 81, 82; 83, 84).There is some evidence of different characteristics for male and female dependent heroin users. Those studies that have reported sex differences found that females were younger (85, 86) and had more suicide attempts and fewer completed suicides (87, 88); different injecting behaviours (89); less education and employment (85); a younger onset of heroin use; more dysfunctional families and exposure to more unfavourable social factors (85;90); greater health service utilization (91; 92); higher standardized mortality ratios (93); more psychological problems (90; 94); and were more likely to sustain abstinence after treatment (95) than men. The evidence regarding sex differences in polysubstance use and dependence among heroin users is mixed, with one study finding no differences in the number

of current or lifetime diagnoses (96), another found higher levels of polydrug use amongst male heroin users (97) and another finding no sex differences in class memberships based on polysubstance use (98).

Although it is a low prevalence disorder, the severity of problems associated with it makes it an important public health issue to understand. Further, within the heroin dependent population, important clinical differences may manifest for different subpopulations including males and females.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SOMATHYC PATHOLOGY

In a recent study one hundred and forty men and women, respectively, could be matched regarding age and recruitment centre; in this sample, the composite score for medical problems was higher in women [0.4 (SD = 0.4)] than in men [0.2 (SD = 0.3); t(277) = −3.01; p < 0.01]. (117) In men some studies reported major risk of progression of HIV and AIDS (12).

Minor Adherence to antiretroviral treatment was evidenced in male heroin dependents(12).

In a recent study, where a total of 991 subjects (73% males), mean age = 25.7 years were interviewed, when doing the analysis with the total sample an interaction between gender and HIV infection was found, indicating that positive HIV serology only had an impact on Health Related Quality of Life (HRQL) of men. (80)

Some studies have found a slower progression to AIDS among HIV positive women, and Jarrin et al say that ―in settings with small gaps in gender inequality and universal access to care, HIV-infected women fare better than their male counterparts in the era of HAART‖(80; 110).

In women major adverse effects were present in drugs utilized to therapy (3)

Major somatic complication (infections, gastroenteric pathologies, muscular-skeleton pathologies, systemic complications) also were present in women (3,5,8,27,31,62) When we observed HIV relapse after antiretroviral treatment, women resulted to have major risk of relapse than men. (9)

Towards the risk HIV sexual transmission female heroin dependents were at major risk than men at the same condiction (36,54).

In women there was major prevalence of positivity to HIV(13,65; 17% vs 11%; 51).

Related to health, female heroin addicted had major impairment of general condition (13,34,47), and also major hospitalization.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN PSYCHIATRIC PATHOLOGY

In men as in women some studies didn’t evidenced

differences in anxiety and major depression(2,17,43,66,68), also in dysthimia, double depression, bipolar disorder (43). Male heroin addicted presented suicidality related to severity of toxicomanic history, aggressiveness, presence of PTSD and problem in work (6).

Major presence of antisocial personality disorder (39), and conduct disturbances (67,70) were present in men.

No differences in prevalence of other personality disorder (77) were evidenced in recent studies.

Some studies reported a major presence of ADHD in men versus women (43), but in other studies ADHD prevalence was similar in women and in men(66).

In women it was reported in many studies that the

psychiatric symptomatology (5,19,45,59,70,73,74) was more severe than same symptomatology reported in men. Axis I disorders were more present in women than in men (77). This data was also evidenced in a study conducted with the purpose of analyzing gender differences in the German trial on heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) which compared HAT with methadone maintenance treatment (MMT). Significant baseline gender differences were found, with females showing a greater extent of mental distress (119).

When we have reaserched differences in mood disorders, it was reported that mood disorders were are more present than in men; in fact, there was a major incidence of depressive symptoms (6,33,39, 52,59, 62,63), dythimia (52,68) but also of maniacal symptoms(52) in male addicted than female addicted. Related to mood disorder, in literature we reaserched gender differences of the presence of suicidality.

Results of our research evidenced that elements as past sexual and physical abuses, poor social supports and low self-esteem were generally related to the presence of suicidality (6) in women.

Females addicted to heroin also had a higher prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours than males. A more detailed analysis of suicidal behaviours and associated characteristics among a sample of a recent study related to gender differences was reported elsewhere (100).

Because of the link evidenced in women between the suicidality and past sexual and physical abuses, we investigated the relationship between severity of psychiatric symptoms and these stressor. A study evidenced that in victims of sexual and physical abuse the severity of psycopathology was greater than women who didn’t (50%>20%) (6).

So, in female addicted suicidality ideation was major present than in male(21); in literature the prevalence of women suicidal attemps was reported to be generally greater in the personal history (16, 35,73), particulary in lifetime history (44% vs 28%), and in the last 12 months

(21% vs 9%) (26) than whose reported in men. Major suicidality was also reported to women that had cocaine addiction (18).

When we have valuted anxiety disturbances in both gender, it was clear that anxiety psychopatology was major present in women than in men.

In fact, the performance anxiety was more (10, 21) reported in female addicted than in male addicted; this data was also valid for simplex phobies (39, 52) where women had more simplex phobies than men. Panic disorders secondary to substance abuse was major in women than in men (45) and the presence of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder also were major in female addicted (52).

Women generally received more pharmacological

treatments than men. A great number of psychiatric complications related to substance abuse were reported in female toward those reported in men(27).

The aggressiveness also was valued in literature. In some studies the presence of aggressiveness wasn’t related to gender but to other data as adverse effects of substance utilized, sleep disturbances and poor social supports(43). In other studies that we analyzed the aggressiveness was

related to gender and to risk of treatment’s drop-out (56). Eating disorders and PTDS were more present in women (32,33,38,39,53,68).

The prevalence of borderline personality disturbance was major in women than in men (39).

In a recent study, it was reported that elements as younger onset of cannabis use, screening for Bipolar Disorder, the presence of major depression, the condiction of heroin overdose, sexual abuses, experiencing adult violence and having time in prison were associated with a greater number of substance dependence diagnoses for males and females (79).

For males, more heroin use per day, antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were also associated with multiple substance dependence diagnoses (79).

For females, childhood emotional neglect, suicide attempt/s and antisocial behaviour (ASB) were associated with increasing substance dependence diagnoses.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SOCIAL SITUATION

Health Related Quality of Life (HRQL) has progressively been applied in the evaluation of health status of patients, including substance users (101, 102, 103).

Poor HRQL has been reported among heroin users starting treatment, being comparable to other chronic disease patients (80).

The more consistent finding was poorer HRQL associated with poly-drug use, HRQL has also been related to socio-demographic variables such as age, educational level or employment status, and the presence of chronic medical conditions, including HIV infection (101,104,105). Although gender has been associated with differences in HRQL in many different population studies, being poorer in women (106,107), no clear differences have been reported in studies on opiate users (101, 104,108,109).

Familiar supports and quality of life were no different in female and in male (32,78).Males were more likely to have experienced childhood physical punishment (79).

In male the prevalence of imprisonment was more represented than in female (1).

When we reaserched the presence of criminality, we evidenced that some studies reported major criminality in males (32,45,54,70) than in females.

On the contrary, other studies reported that the presence of criminality in both genders was similar, at the baseline and at follow up (24,29) valutations. Some studies reported that males had a longer total time spent in prison and longer sentences than females. Addicted males had a higher risk of incarceration, criminal activity and arrest, and committed different types of crime than females (79).

Other studies showed the data that men had more legal problems regarding incarcerations and they were more often living alone or were homeless (117).

Sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect were also common. (99).

Familiar history of alcohol abuse was similar in both genders (35,78).

In literature it was reported a recent study that analyzes 1513 heroin addicted. In this study half of the participants evidenced that one or both parents had a drug and/or alcohol problem.(79)

evident that male addicted were more singles than female addicted (61).

In female conducts at risk were more present than in men

(prostitution, needle change (1)). Ongoing prostitution was found to influence drug use outcomes. (119)

Condictions as house instability, unemployment, economic

problems (1,40,41,45,55,64,73), major functional

compromise situations (7, 27) also were more present in female heroin addicted. Several studies have shown that interpersonal relationships may have contradictory effects for women who were addicts; they could be a source of support, but they couls also contribute to ongoing problems and possibly relapse (7, 32).

Women drug users may also be isolated from other sources of social support by their partners, particularly if they have a history of intimate-partner violence (116)

Women cohabited more frequently with toxicomanic partners (7, 34, 45, 76) than men.

There were in these female subjects major request of assistance for familiar problems, or for traumatic experiences (32).

Females were more than four times more likely than males to have experienced unwanted sexual activity after the age of 18, either through the use of physical violence, threats of physical violence, blackmail, or the threat of relationship break-up (79).

Women were also more likely to be victims of adult violence (pushing, grabbing, shoving, slapping, hitting, kicking, punching, choking, and strangling) or threats of violence (hitting, and threatened with a weapon), whilst males were more likely to be perpetrators of violence.

Females were more likely than males to have had a poor relationship with their mother during childhood and adolescence, and to experience problematic parental substance use, childhood sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and emotional neglect (79).

Males were more likely to have experienced childhood physical punishment.

Lower school- attendance index was present in women (35,45); it was valid also for the presence of emigration (35), the presence in personal history of sexual, physical, psychological abuse (46,62,74,78). Females were younger on average than males, more likely to be married, and to be

receiving a government benefit than males, however there were no sex differences in unemployment rates or level of education (79).

In women there was a major familiarity for psychiatric disease and abuse disorders (44) than in men.

Problematic families were more present in female (60,71) then in males. Women were more coupled than men (61).

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN PAST HISTORY OF SUBSTANCE

ABUSE

Some studies reported that in men as in women the severity of past history of Substance Abuse was similar (66).

Male students of superior school abused more in cannabinoid and tobacco than females (14); on contrary, female students of inferior school smoke morely than their male same age (14).

In general, cocaine addicted males utilized more money, more sedative drugs, more alcohol, and more cannabinoid

(42) than females.

In women other studies reported a major severity of pregress hystory of Substance Abuse (21,22,47), but this date didn’t seem to be true for cocaine dependence; in fact it seem that the history of cocaine toxicomanic conduct was more brief than in male (42). Women had more problems related to substance abuse than men(22).In a recent study one hundred and forty heroin addicted men and women, respectively, could be matched regarding age and recruitment centre; in this sample the age at beginning of regular consumption (men mean age 20.55, women mean age 21.4) did not differ significantly between both groups (t(242.1) = −1.16; p = 0.25) (117). Slightly more males than females had experienced a heroin overdose requiring medical treatment. There were no sex differences in the experience of multiple overdoses (79). A recent study valued 140 addicted males and 140 addicted females and their dependence history; in this clinical sample, the number of detoxification treatments was not different between men and women, but more men had been in long-term rehabilitation treatment than women (51.9 vs. 17.5%; χ2(9) = 23.73; p < 0.01) (117).

PROXIMAL HISTORY OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Analysing the differences of the substance abuse at the moment of the first visit, it seem that males utilized more benzodiazepines (7), alcohol (54,58), opioid (8, 73), and THC (58) towards females. The similarity in both gender was in the frequency of the use of substances, (4) but not in the type of first substance utilized (40).

Female addicted utilized not only heroin (5) and opioid substances (15), but also cocaine (34).

Differently of males, females asked primarily medical treatment and it was valid in particular for complications related to substance abuse and not for HIV complications (15).

Females had generally more insight of disease (15) and they were more early than males to request of medical assistance (8,72). Moreover, some studies reported that women with substance use problems were less likely than men to enter treatment over the lifetime (115), and men were more likely to be coerced into treatment by external mandates (115).Although women might be less likely to enter substance abuse treatment

than men over the course of the lifetime, once they enter treatment, gender itself was not a predictor of treatment retention, completion, or outcome (118). In a recent study the relapse to heroin use after a period of abstinence from heroin was reported by 83.4% of participants, with males slightly more likely than females to have ever relapsed (79).

No gender differences were observed in the proportion of those who had a previous overdose experience or had experienced an opiate overdose in the last 12 months before primarily medical treatment. (80)

Women reported worse HRQL, but contrary to males having had an opiate overdose, the contact with a psychiatrist or having ever been on methadone treatment during the preceding 12 months were not found to be associated with it (80).

LONGITUDINAL HISTORY

In literature the age of first drug contact was similar in both genders (29,51), so the severity of abuse (20. 35,66,69).

It was different in severity of toxicomanic history (11,20,32,63,72,73); in fact males seem to have more severity of the history than females. There were no sex differences in age of initiation to drug or alcohol use, or in onset of heroin dependence.

Some studies reported that the age of males was later than females in the treatment ingress (30,59,74), but other studies didn’t evidence this difference (29). In literature it was also reported that males had been in treatment for less time and sought treatment at an older age than females.

Addicted males utilized more THC, hallucinogen

substance(50) and more utilize of endovenous access than female addicted (72).

Males were more likely than females to receive a lifetime diagnosis for cannabis, stimulant or alcohol dependence (79). There were no sex differences in the prevalence of sedative,

cocaine or nicotine dependence. The most common

introduction to heroin and its use was through a friend (79). However women were more likely than men to be introduced to heroin by a partner, boyfriend or spouse, whereas men were more likely than women to be introduced to heroin by a friend. There were no sex differences in age of initiation to drug or alcohol use, or in onset of heroin dependence.

On average, females sought treatment for heroin dependence at a younger age than males (79). Onset of cannabis use and first alcohol intoxication occurred, on average, at about the same age (~14 years) (79).

Males presented more possibility to have medical assistance (30) and they stayed in treatment - as days as ingress in treatment- more than females (50). Other studies reported that there were no differences in treatments received and in the abuse history (76,78) in males and in females.

When we observed in literature differences in one year of follow-up, no differences in both genders there were observed in the reduction of substance abuse, health problems and criminality problems (34).

Analysing the female longitudinal history, we evidence in literature some interesting date.

It was observed in fact, in addicted females a major progression from abuse to dependence (20,57), a major utilize of addictional method of substance abuse (57), a late age of exordium (20, 59), a rapid development of organic disease (20), a less time intercourse from first use of substance and first medical assistance (20,74), a less time of toxicomanic

history (20), a major request of treatment independently by physical complications or external intervents (20,48,49) towards addicted males. Sex differences were noted in the rate of escalation ofdrug use in which women tend to increase their drug intake morerapidly than men. (120)

In literature was also reported that after treatments women reduced the utilize of substance abuse (8).

AIM OF RESEARCH

The aim of our research was to search gender differences generally in a sample of 1,090 heroin addicted and into 368 heroin addicts that were at first treatment. In both samples, the data that we valued were demographic characteristics, the presence of related somatic diseases (RSD), the mental status (Psychophatological Symptoms) refers to symptomatic patients and the social adjustment.

MATERIAL E METHOD SAMPLE

agonist treatment between 1994 and 2005 at the Dual Diagnosis Unit of the University Hospital in Pisa, Italy and in this sample we analyze 368 heroin addicts at first treatment. All patients received a diagnosis of opioid dependence with physical dependence (according to DSM III/IIIR/IV criteria) and gave their informed consent for study participation.

Addiction-related information was collected by means of the Drug Addiction History Rating Scale (111) administered by a psychiatrist.

The DAH-RS is a multi-scale questionnaire comprised of the following categories: demographic data, physical health (hepatic, vascular and lymphatic pathology, gastrointestinal disorders, sexual disorders, dental pathology, and HIV seropositivity), mental health (awareness of illness, memory disorders, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, aggression, thought disorders, and sensory perception disorders), substances abuse (use of alcohol, opiates, central nervous system (CNS) depressants, CNS stimulants, hallucinogens, phencyclidine, cannabis, inhalants, and polysubstance abuse), social adjustment and environmental factors (employment, family, gender, socialization and leisure time, and legal problems), clinical characteristics as frequency of drug use,

patterns of use, phase, nosology, and treatment history (previous and current treatments). Items are set up so as to elicit dichotomous answers (yes/no).

Regarding toxicological urinalyses, the enzyme multiplied immunotechniques for opiates, methadone, benzodiazepines,

hypnotics, cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogens,

cannabinoids, and inhalants was used. Problematic alcohol use was intended as a history of frequent (more than weekly) episodes of intoxication, with resultant impairment of working, family and interpersonal adjustment, and alcohol-related legal trouble.

DATA ANALYSIS

We compared demographic and clinical features by gender by means of the Student t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categories.

To describe the pattern of substance (ab)use, we used the following DAH-RS items: heroin intake (item 57), modality of use (item 58), the clinical phase of illness (item 60), presence of psychosocial stressors before using heroin (item 61), presence or absence of a history of periodic self-detoxifications (item 59), use of morphine and other painkillers (item 37), heroin

(item 36), illegal methadone (item 39), alcohol (item 35), ketamine (item 41), benzodiazepines (item 43), hypnotics (item 44), CNS stimulants (cocaine, amphetamines, Ecstasy—items 47, 43 and), classic hallucinogens (LSD; item 48), cannabinoids (item 53), inhalants (item 54), and polyabuse (item 55). Polyabuse was defined as patients abusing heroin and two or more other substances.

A factor analysis was performed on the above-reported abused substances for 1,090 patients in order to identify possible composite dimensions. The initial factors were extracted by

means of principal component analysis (type 2) and then rotated according to varimax criteria in order to achieve a simple structure. This simplification is equivalent to maximising the variance of the squared loading in each column. The criterion used to select the number of factors was an eingen value greater than 1. Item loadings with absolute values greater than 0.4 were used to describe the factors. This procedure makes it possible to minimise the correlations between the factors, so allowing their optimisation as classificatory tools for each subject. In order to

compare factorial scores, we resorted to a nonparametric test (Mann-Whitney), since the score distribution was not a Gaussian one.

Statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS package (version 4.0 by SPSS Inc).

As this is an exploratory study, statistical tests were considered significant at the p < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

SOCIO DEMOGRAPHIC DATA

We valued socio demographic characteristics of both gender at treatment entry. Males and females differed in employment rate (37.7% of males were blue collar workers, 37.4% were unemployed; 23.9% of females were blue collar workers and 46.7% unemployed; df = 2; chi-square16.61; p = 0.0002).

A total of 52.1% of males had blue collar worker parents and 11.8% unemployed parents, whereas 40.5% of females had blue collar worker parents and 17.4% had unemployed parents (df = 2; chi square 11.92; p = 0.002).

A total of 31.5% of males were married versus 47.9% of females (df = 1; chi square 23.07; p = 0.0000).

At the first treatment a total of 38.4 males % were blue collar workers and 26.6% unemployed, whereas in females a total of 19.6% were blue collar workers and 40.2% were unemployed (chi square 22.63; p=0.00006). Males and females differed also in parental occupation; in fact, 48.5% of males had white collar worker parents versus 30.2% of females parents. At the first treatment, males and females were different in civil status (70.8% of males were single vs 60.8% of females).

In the total sample there weren’t statistically significant differences between males and females with regard to age, income, education, place of birth or of residence, type of housing and whether or not they received public welfare benefits at treatment entry.

When we observed those data at the first treatment, it resulted that in females as in males the same place of birth was the same place of residence (Central Italy) but there weren’t statistically significant differences between males and females with regard

to age, income, type of housing and whether or not they received public welfare benefits at treatment entry. Regard education, there were a significant interruption of studying in both gender; in fact 83.6% of males stopped studying, also 69.2% of females stopped it. (see Table 1)

RELATED SOMATIC DISEASES (RSD) DATA

According to gender, there weren’t any differences in the presence of related somatic diseases (RSD); in fact the same percentage of Hepatic, Vascolar, Gastrointestinal, Sexual, Dental, Lymphadenitis disease AND HIV+ was observed in both gender. The disease more represented was hepatic disease ( in males 36.4%, in females 37.5%). For more detailes, see Table 2)

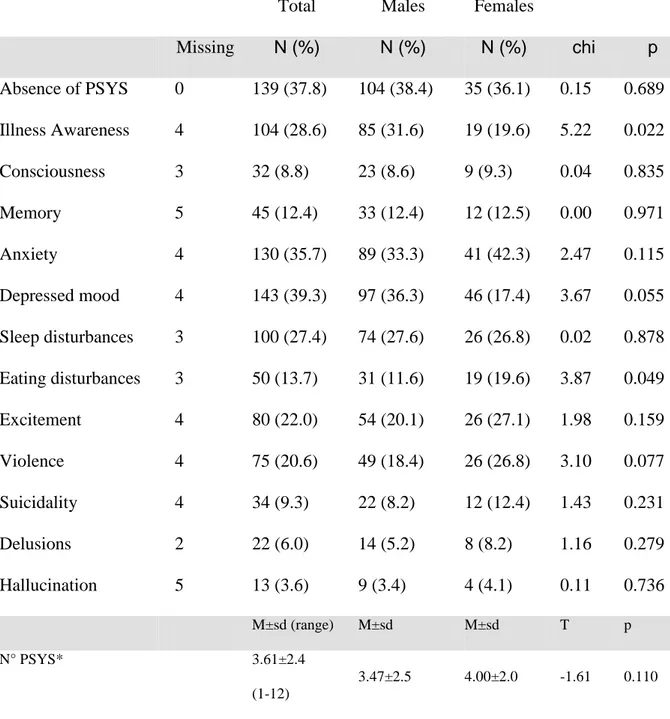

MENTAL STATUS DATA

When we analyzed the Mental Status of 368 heroin addicts at first treatment according to gender and specifically the number of Psychophatological Symptoms (N°PSYS)

refers to symptomatic patients some interesting data were evidenced.

For the Illness Awareness males resulted to be more aware than women (31.6% vs 19.6%)

On the observation of mood symptoms at the time of the first treatment there were also unexpected data; in fact 36.3% of addicted males presented depressed mood towards 17.4% of females (p=0.055). No statistical significant differences were observed in the presence of other mood symptoms as Excitement, Violence, Suicidality and Sleep disturbances.

Psycothic symptoms as Delusions Hallucination had the same prevalence in both genders.

Males and females had the similar percentage in the presence of anxiety symptoms (33.3% vs 42.3%), but they were different in the presence of Eating disturbance. Female in fact had more Eating Symptoms than men, and this difference was statistical significant (19.6% vs 11.6%; p=0.049)

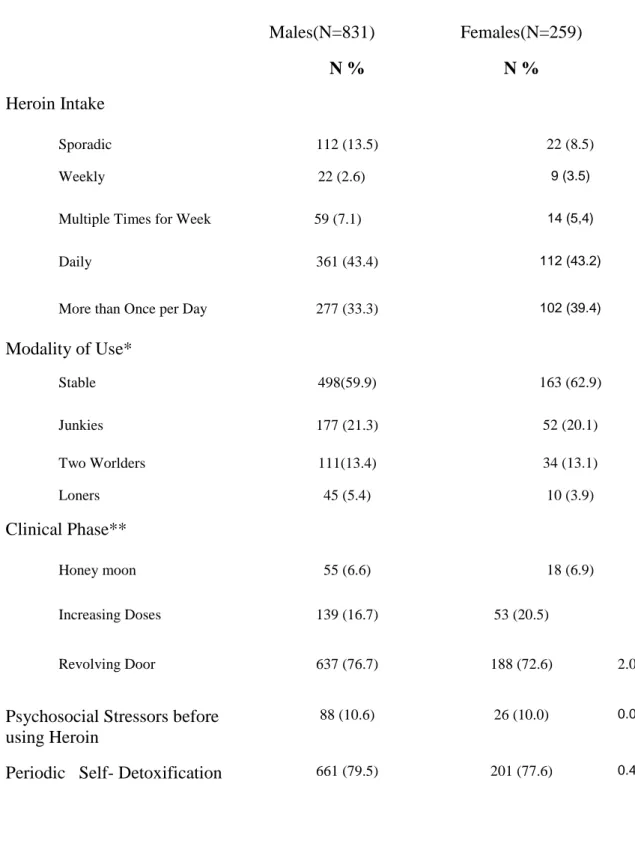

PATTERN OF ABUSE AT TREATMENT ENTRY

Analyzing the history of heroin abuse, when we valued in all sample elements as for the frequency of consumption, it was evidenced that the majority of treatment-seeking heroin addicts used heroin on at least a daily basis. A small minority decided to start treatment during periods of weekly or sporadic use.

No gender-related difference was found with respect to the frequency of heroin consumption.

In the total sample, as for the addictive mode, the majority of heroin addicts remained ―stable‖ (maintained a certain level of work and social adjustment); one out of five was a ―junkie‖ (engaged in violent and disruptive street life). Approximately 13% swung between social adjustment and disruptive behavior (―two-worlders‖), while the smallest minority stuck to the ―loner‖ mode (avoided dealing with other addicts).

The great majority of treatment-seeking heroin addicts had entered the revolving door phase: it is typical of these addicts to be able to stop using heroin from time to time, for periods of variable length, between relapses. Ten percent of subjects

started using heroin in the context of some form of psychosocial stress. The natural history of addiction did not vary according to gender. (table 4)

SUBSTANCE ABUSE AT TREATMENT ENTRY

Regard the utilize of other substances, it was clear that gender did not influence the use patterns for opioid painkillers, alcohol, cocaine, hallucinogenic drugs, inhalants or for polyabuse. Males tended to use heroin as their opiate of choice, and were most likely to combine it with cannabis. Females were more likely to resort to street methadone, and use ketamine, benzodiazepines, hypnotic drugs and amphetamines in addition to their drug of choice (heroin). For more detailes, see table 5.

The factorial analysis (Table 6) defines three dimensions: the first (30.7% of variance) corresponds to mixed use of cannabis, cocaine and amphetamines, hallucinogenic drugs and alcohol. The second (11.7% of variance) corresponds to concurrent depressant (benzodiazepine and hypnotics) and painkiller use. The third (9.7% of variance) corresponds to addicts who resort to anaesthetics (ketamine) and inhalants.

Of these patterns (Table 4) the first was rather typical of males

and the second one of females. No link with gender was found for the third. Treatment seeking male heroin addicts, then, were more likely to be current polyabusers of all available substances. By contrast, female peers quite specifically resorted to depressants and painkillers in combination with opiates. The male-oriented factor accounts for a rate of variance three times

greater than the female-oriented factor.

DISCUSSION

The few observed psychosocial differences may just mirror different roles, with special regard to Italian social stereotypes, such as a lower likelihood of women working or have a blue

collar job (which may not be seen as deviating from the norm in female addicts but rather is expected for the general Italian female population. As for marital status, women are more likely

to be married, although mostly to addicted partners. Partners may seek treatment independently, but marrying another addict

is more typical of females than of males, which makes the difference in marital status not necessarily correspondent to better psychosocial support or adjustment.

Although heroin addicts obviously, by definition, engaged in heroin consumption, painkiller abuse has been spreading and increasing in many countries (112). Our data indicate that treatment-seeking male heroin addicts consume greater amounts of heroin as a trend (8) while women, contrary to some other reports (5) are rather prone to combine smaller amounts of heroin with street methadone and prescription painkillers. This may mean that women are at higher risk of entering the opiate addiction pathophysiology through initial painkiller use, and more often resort to illicit methadone treatment to cope with painkiller addiction; this pattern presents a higher risk of accidental fatalities (113;114). In our subjects, heroin-addicted females seemed to switch, at least partially, to opiate analgesics as a secondary addictive pattern, possibly coupled with street methadone. The clinical meaning of street methadone consumption has not been thoroughly investigated, but some authors indicate that the use of illegal methadone as drug of choice may increase along with the diversion of prescribed methadone.

In a recent observation we proposed that, at least in Italy, resorting to street methadone does not seem to be a surrogate form of heroin addiction, but rather represents a type of harm reduction, with treatment seeking occurring soon after (115). In the present study illegal methadone use tends to be associated with the abuse of analgesics, rather than heroin, at least for female heroin addicts. Also in this case, a possible explanation may be that of an attempt to self-medicate their addiction in subjects who will later apply for actual treatment in a therapeutic setting. In other words, treatment-seeking female heroin addicts may substitute cheaper and more available opiates for heroin, possibly combining them with sedatives or benzodiazepines, in the attempt to deal with their addiction or withdrawal states. Interestingly, male addicts do not seem to engage in such a substitutive pattern but tend to maintain traditional polyabuse (stimulants, cannabis, alcohol). Also, our data do not confirm benzodiazepine abuse to be more relevant for male addicts (7).

As for alcohol abuse alone, no gender-related difference emerged. Nevertheless, alcohol is featured within the polyabuse pattern (derived from the factorial analysis) on which males

score higher. Therefore, our data go along with previous findings of greater proneness to alcohol use by male heroin addicts (54,58).

Cannabis is also more likely to be abused by males, in agreement with previous findings (58) while cocaine abuse does not appear to be gender-related, in contrast to what other authors have indicated (23). Nevertheless, women do abuse methamphetamines to a greater extent, as a trend. Our population of treatment-seeking heroin addicts appears to be systematically engaged in polyabuse, by three alternative patterns. These three patterns differ from one another: the mixed polyabuse pattern features alcohol and illegal drugs, with a strong correlation between levels of polyabuse and levels of heroin consumption, and a minor correlation with street methadone and opiate analgesics. The second abuse pattern features opiate analgesics, tranquillizers and sedative drugs, with no relation to heroin consumption levels, but a certain link with street methadone use. The third pattern includes ketamine and inhalants, excluding opiate analgesics and street methadone, and with an inverse relationship to heroin consumption. The first patterns is rather typical of males, the second one of females and the third one has no link with

gender. Females addicts tend to be more heterogeneous in their substance choice, which is less predictable, whereas one male stereotype is definable along the first factor (specific and of significant weight). Therefore, different factors, either biological or social, may account for such heterogeneity among female addicts, beyond gender-related features. The greater clash between a violent and aggressive drug-related lifestyle and traditional female roles may account for greater depressant and ketamine use, in order to buffer gender-specific psychological stress.

Women may be seen as ―low risk‖ addicts or more reasonable drug users and be allowed a higher number of prescriptions or supplies or convince others to illegally give them legal drugs.

On the whole, female heroin addicts tended to detach from illegal substances before seeking treatment. Such behavior is not clearly interpretable: one possible explanation is that

hormonal factors contribute to amplify neuroendocrine functions impaired by fast-acting opiates (heroin), thus increasing the need for slow-acting and stable cross-reacting drugs (methadone, painkillers). In that case, switching to abuse of depressants and other opiates would mirror a higher level of opioid disregulation as a prelude to seeking treatment.

A second hypothesis is that female patterns of psychiatric comorbidity (a higher rate of anxiety disorders) (10,45) and a higher level of dysthymia combined with cyclothymia (6; 39; 33) are specifically sensitive to the action of slow-acting opiates.

Another hypothesis is that remaining in the drug-related environment is more distressing for women, who also have a lower rate of antisocial personality traits (39).

On the whole, women may count on greater social acceptance of drug-seeking behaviors, and exploit that gender-related prejudice to keep away from a street environment for as long as

possible. When it is no longer possible, depressant and inhalant substance use may be a way of coping with these gender-specific stresses. Thus, different stages may correspond to different polyabuse patterns. So, Addiction is one such disease that appears to have sex-specific traits and vulnerabilities that may be linked to stress. Sex differences are noted in the rate of escalation of drug use in which women tend to increase their drug intake morerapidly than men.

Lastly, it may be that women just reach a breaking point with addictive behaviors earlier, for a combination of reasons, and spontaneously switch to a pattern of self-handled abuse which

is a step towards treatment, since it is conceived as an attempt to balance opioid functions by tonic drugs. Otherwise, treatment-seeking heroin addicts apply for treatment in a typical state of poly-intoxication, which indicates deeper engagement in self-stimulation by fast-acting drugs.

Apart from patterns of polyabuse, other addictive features (mode, phase of illness, psychosocial stress, periodic abstinence and frequency of use) did not differ according to gender

in our population.

CONCLUSION

The main limitation of this study is that it relies on an analysis of subjects at the point they choose to enter a treatment program. Exactly how their conditions may mirror those patients in the general population is obviously unclear. Within the group of those who do not make it to clinical observation are those who may actually overdose and die from their illicit use of opioid substances. This may be particularly important in those patients who combine street methadone with opioid pain

killers (in this study predominantly a female pattern), who more easily make mistakes in the amount of substances that is safe to ingest. Therefore certain patients may not make it into this study because of differential effects on their long-term availability and longevity.

Some reported data has suggested that gender does not have a definite influence on heroin addiction with respect to patterns of substance abuse. Nevertheless, female heroin addicts who apply for treatment display a trend towards the use of substitutive opiate drugs, such as prescription painkillers and street methadone, possibly combined with depressants. Such behavior may lead to a relative stabilization due to fast-acting use of opioid-related substances, and maybe a partial craving control with resultant diminished discomfort. This pattern is rarely

encountered in males who maintain heroin use, often times combined with cannabis or polysubstances.

BIBLIOGRAFY

1. Breen C., Roxburgh A., Degenhardt L.: Gender differences among regular injecting drug users in Sydney, Australia, 1996-2003. Drug Alcohol Rev., 2005 Jul; 24 (4): 353-8.

2. Cook L.S., Epperson L., Gariti P.: Determining the need for gender-specific chemical dependence treatment: assessment of treatment variables. Am J Addict., 2005 Jul-Sep; 14(4):328-38. 3. Schoeder J.R., Schmittner J.P., Epstein D.H., Preston K.L.: Adverse events among patients in a behavioral treatment trial for heroin and cocaine dependence: effects of age, race, and gender. Drug Alcohol Depend., 2005 Oct 1; 80(1): 45-51.

4. Ridenour T.A., Maldonado-Molina M., Compton W.M., Spitznagel E.L., Cottler L.B.: Factors associated with the transition from abuse to dependence among substance abusers: implications for a measure of addictive liability. Drug Alcohol Depend., 2005 Oct 1; 80(1):1-14. Epub 2005 Apr 26.

5. Mann K., Ackermann K., Croissant B., Mundle G. Nakovics H., Diehl A.: Neuroimaging for gender differences in alcohol dependence: are women more vulnerable? Alcohol Clin

6. Benda B.B.: Gender differences in predictors of suicidal thoughts and attemps among homeless veterans that abuse substances. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005 Feb; 35(1): 106- 16

7. Grella C.E., Scott C.K., Foss M.A.: Gender differences in long-term drug treatment outcomes in Chicago PETS. J Subst Abuse Treat., 2005; 28 Suppl 1: S3-12.

8. Giacomuzzi S.M., Riemer Y., Ertl M., Kemmler G., Rossler H., Hinterhuber H., Kurz M.: Gender differences in health-related quality of life on admission to a maintenance treatment program. Eur Addict Res. 2005; 11(2): 69-75.

9. Kuyper L.M., Wood E., Montaner J.S., Yip B., O’connel J.M., Hogg R.S.: Gender differences in HIV-1 RNA rebound attributed to incomplete antiretroviral adherence among

HIV-infected patients in a population-based cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004 Dec 1; 37(4): 1470-6.

10. Zimmermann G., Pin M.A., Krenz S., Bouchat A., Favrat B., Besson J., Zullino D.F.: Prevalence of social phobia in a clinical sample of drug dependent patients. J Affect Disord. 2004 Nov 15;83(1): 83-7.

11. Gordon S.M., Mulvaney F., Rowan A.: Characteristics of adolescents in residential treatment for heroin dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004 Aug; 30(3): 593-603.

12. Garcia de la Hera M., Ferreros I., del Amo J., Garcia de Olalla P., Perez Hoyos S., Muga R., del Romero J., Guerriero R., Hernandez-Aguado I.; GEMES: Gender differences in

progression to AIDS and death from HIV seroconversion in a cohort of injecting drug users from 1986 to 2001. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004 Nov; 58(11): 944-50.

13. Puigdollers E., Domingo-Salvany A., Brugal M.T., Torrens M., Alvaros J., Castillo C., Magri N., Martin S., Vazquez J.M.: Characteristics of heroin addicts entering methadone

maintenance treatment: quality of life and gender. Subst Use Misuse. 2004 Jul; 39(9): 1353-68.

14. Latimer W.W., Floyd L.J., Vasquez M., O’Brien M., Arzola A., Rivera N.: Substance use among school-based youths in Puerto Rico: differences between gender and grade levels. Addict Behav. 2004 Nov; 29(8): 1659-64.

15. Boyd S.J., Thomas-Gosain N.F., Umbricht A., Tucker M.J., Leslie J.M., Chaisson R.E.,

Preston K.L.: Gender differences in indices of opioid dependency and medical comorbidityin a population of hospitalized HIV-infected African-Americans. Am J Addict. 2004 May-Jun; 13(3): 281-91.

16. Pettinati H.M., Dundon W., Lipkin C.: Gender differences in response to sertraline pharmacotherapy in Type A alcohol dependence. Am J Addict. 2004 May-Jun; 13(3): 236-47.

17. Valentiner D.P., Mounts N.S., Deacon B.J.: Panic attacks, depression and anxiety symptoms, and substance abuse behaviors during late adolescence. J Anxiety Disord. 2004; 18(5): 573-85.

18. Darke S., Kaye S.: Attempted suicide among injecting and non injecting cocaine users in Sydney, Australia. J Urban Health. 2004 Sep; 81(3): 505-15.

19. Milani R.M., Parrott A.C., Turner J.J., Fox H.C.: Gender differences in self-reported anxiety, depression, an somatization among ecstasy/MDMA polydrug users,

alcohol/tobacco users, and nondrug users. Addict Behav. 2004 Jul; 29(5): 965-71.

20. Hernandez-Avila C.A., Rounsaville B.J., Kranzler H.R.: Opioid-, cannabis- and alcohol dependent

women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 Jun 11; 74(3): 265-72.

21. De Wilde J., Soyez V., Broekaert E., Rosseel Y., Kaplan C., Larsson J. : Problem severity profiles of substance abusing women in European Therapeutic Communities: influence of psychiatric problems. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004 Jun; 26(4): 243-51.

22. Stevens S.J., Estrada B., Murphy B.S., McKnight K.M., Tims F.: Gender differences in substance use, mental health, and criminal justice involvement of adolescents at treatment entry and at three, six, twelve and thirty month follow-up. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2004 Mar; 36(1): 13-25.

23. Holdcraft L.C., Iacono W.G.: Cross-generational effects on gender differences in psychoactive drug abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 May 10; 74(2): 147-58.

24. Rogne Gjeruldsen S., Myrvang B., Opjordsmoen S.: Criminality in drug addicts: a follow-up study over 25 years. Eur Addict Res. 2004; 10(2): 49-55.

25. Kelly T.M., Cornelius J.R., Clark D.B.: Psychiatric disorders and attempted suicide among adolescents with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 Jan 7; 73(1): 87-97.

26. Darke S., Ross J., Lynskey M., Teesson M.: Attempted suicide among entrants to three treatment modalities for heroin

dependence in the Australian Treatment Outcome Study

(ATOS): prevalence and risk factors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 Jan 7; 73(1): 1-10.6

27. Greenfield S.F., Manwani S.G., Nargiso J.E.:

Epidemiology of substance use disorders in women. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003 Sep; 30(3): 413-46.

28. Latka M.: Drug-using women need comprehensive sexual risk reduction interventions. Clin Infect Dis. 2003 Dec 15; 37 Suppl 5: S445-50.

29. Hser Y.I., Huang D., Teruya C., Douglas Anglin M.: Gender comparisons of drug abuse treatment outcomes and predictors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 Dec 11; 72(3): 255-64. 30. Downey L., Rosengren D.B., Donovan D.M.: Gender, waitlists, and outcomes for public sector drug treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003 Jul; 25(1): 19-28.

31. Fernando D., Schilling R.F., Fontdevila J., El-Bassel N.: Predictors of sharing drugs among injection drug users in the South Bronx: implications for HIV transmission. Psychoactive Drugs. 2003 Apr-Jun; 35(2): 227-36.

32. Grella C.E.: Effects of gender and diagnosis on addiction history, treatment utilization, and psychosocial functioning among a dually-diagnosed sample in drug treatment. J

Psychoactive drugs. 2003 may; 35 Suppl 1: 169-79.

33. Shrier L.A., Harris S.K., Kurland M., Knight J.R.: Substance use problems and associated psychiatric symptoms among adolescents in primary care. Pediatrics. 2003 Jun; 111(6 Pt 1):e699-705.

34. Stewart D., Gossop M., Marsden J., Kidd T., Treacy S.: Similarities in outcomes for men and women after drug misuse treatment: results from the National Treatment Outcome

Research Study (NTORS). Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003 Mar; 22(1): 35-41.

35. Zilberman M.L., Hochgraf P.B., Andrade A.G.: Gender differences in treatment-seeking Brazilian drug-dependent individuals. Subst Abus. 2003 Mar; 24(1): 17-25.

36. Evans J.L., Hahn J.A., Page-Shafer K., Lum P.J., Stein E.S., Davidson P.J., Moss A.R.: Gender differences in sexual and injection risk behavior among active young injection drug users in San Francisco (the UFO Study). J Urban Health. 2003 Mar; 80(1): 137-46.

37. Stevens S.J., Murphy B.S., McKnight K.: Traumatic stress and gender differences in relationship to substance abuse, mental health, psysical health, and HIV risk behavior in a

Maltreat. 2003 Feb; 8(1): 46-57.

38. Titus J.C., Dennis M.L., White W.L., Scott C.K., Funk R.R.: Gender differences in victimization severity and outcomes among adolescents treated for substance abuse. Child Maltreat. 2003 Feb; 8(1): 3-6.

39. Landheim A.S., Bakken K., Vaglum P.: Gender differences in the prevalence of symptom disorders and personality disorders among poly-substance abusers and pure alcoholics. Substance abusers treated in two counties in Norway. Eur Addict Res. 2003 Jan; 9(1): 8-17.

40. Callaghan R.C., Cunningham J.A.: Gender differences in detoxification: predictors of completion and re-admission. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002 Dec; 23(4): 339-407.

41. Schoenbaum E.E., Lo Y., Floris-Moore M.: Predictors of hospitalization for HIV-positive women and men drug users, 1996-2000. Public Health Rep. 2002; 117 Suppl 1: S60-6.

42. Wong C.J., Badger G.J., Sigmon S.C., Higgins S.T.: Examining possible gender differences among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002 Aug; 10(3): 316-23.

43. Latimer W.W., Stone A.L., Voight A., Winters K.C., August G.J.: Gender differences in psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents with substance use disorders. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002 Aug ; 10(3): 310-15.

44. Di Nitto D.M., Webb D.K., Rubin A.: Gender differences in dually-diagnosed clients receiving chemical dependency treatment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002 Jan-Mar; 3(1): 105- 17.

45. Kecskes I., Rihmer Z., Kiss K., Sarai T., Szabo A., Kiss G.H.: Gender differences in panic disorder symptoms and illicit drug use among young people in Hungary. Eur Psychiatry. 2002 Mar; 17(1): 29-32.7

46. Robinson E.A., Brower K.J., Gomberg E.S.: Explaining unexpected gender differences in hostility among persons seeking treatment for substance use disorders. J Stud Alcohol. 2001Sep; 62(5): 667-74.

47. Langan N.P.,Pelissier B.M.: Gender differences among prisoners in drug treatment. J Subst Abuse. 2001; 13(3): 291-301.

48. Haas A.L., Peters R.H.: Development of substance abuse problems among drug-involved offenders. Evidence for the telescoping effect. J Subst Abuse. 2000; 12(3): 241-53.

49. Rivers S.M., Greenbaum R.L., Goldberg E.: Hospital-based adolescent substance abuse treatment: comorbidity, outcomes, and gender. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001 Apr ; 189(4): 229-37.

50. Westermeyer J., Boediker A.E.: Course, severity, and treatment of substance abuse among women versus men. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2000 Nov; 26(4): 523-35.

51. Doherty M.C., Garfein R.S., Monterroso E., Latkin C., Vlahov D.: Gender differences in the initiation of injection drug use among young adults. J Urban Health. 2000 Sep; 77(3): 396- 414.

52. Compton WM3rd, Cottler L.B., Ben Abdallah A., Phelps D.L., Spitznagel E.L., Horton J.C.: Substance dependence and other psychatric disorders among drug dependent subjects: race and gender correlates. Am J Addict. 2000 Spring; 9(2): 113-25. 53. Lipschitz D.S., Grilo C.M., Fehon D., McGlashan T.M., Southwick S.M.: Gender differences in the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and problematic substance use in psychiatric inpatient adolescents. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000 Jun; 188(6) : 349-56.

54. Rowan-Szal G.A., Chatham L.R., Joe G.W., Simpson D.D.: Services provided during methadone treatment. A gender comparison. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000 Jul; 19(1): 7-14.

55. Royse D., Leukefeld C., Logan T.K., Dennis M. Wechsberg W., Hoffman J., Cottler L.,Inciardi J.: Homelessness and gender in out-of-treatment drug users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000 May; 26(2): 283-96.

56. Petry N.M., Bickel W.K.: Gender differences in hostility of opioid-dependent outpatients: role in early treatment termination. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000 Feb 1; 58(1-2): 27-33.

57. McCance-Katz E.F., Carrol K.M., Rounsaville B.J.: Gender differences in treatment-seeking cocaine abusers – implication for treatment and prognosis. Am J Addict. 1999 Fall; 8(4): 300-11.

58. Bretteville-Jensen A.L.: Gender, heroin consumption and economic behaviour. Health Econ.1999 Aug; 8(5): 379-89. 59. Brady K.T., Randall C.L.: Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatr ClinNorth Am. 1999 Jun; 22(2): 241-52.

60. Chatham L.R., Hiller M.L., Rowan-Szal G.A., Joe G.W., Simpson D.D.: Gender differences at admission and follow-up in a sample of methadone maintenance clients. Subst Use

Misuse. 1999 Jun; 34(8): 1137-65.

61. Stueland D., Seavecki M. 3rd: Relationship of gender to characteristics of patients referred to a Rural Wisconsin Addiction Treatment Unit. WMJ. 1999 Jan-Feb; 98(1): 42-7. 62. Brunette M., Drake R.E.: Gender differences in homeless persons with schizophrenia and substance abuse. Community Ment Health J. 1998 Dec; 34(6): 627-42.

63. Magura S., Kang S.Y., Rosenblum A., Handelsman L., Foote J.: Gender differences in psychiatric comorbidity among cocaine-using opiate addicts. J Addict Dis. 1998; 17(3): 49- 61.

64. Chen C.K., Shu L.W., Liang P.L., Hung T.M., Lin S.K.: Drug use patterns and gender differences among heroin addicts hospitalized for detoxification. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1998 Jun; 21(2): 172-8.

65. Jang K.L., Livesley W.J., Vernon P.A.: Gender-specific etiological differences in alcohol and drug problems: a behavioural genetic analysis. Addiction. 1997 Oct; 92(10): 1265-76.

66. Whitmore E.A., Mikulich S.K., Thompson L.L., Riggs P.D., Aarons G.A., Crowley T.J.: Influences on adolescent substance dependence: conduct disorder, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and gender. Dug Alcohol Depend. 1997 Aug 25; 47(2): 87-97.

67. Brown J.M., Nixon S.J.: Gender and drug differences in antisocial personality disorder. J Clin Psychol. 1997 Jun; 53(4): 301-5.

68. Grilo C.M., Martino S., Walzer M.L., Becker D.F., Edell W.S., McGlashan T.H.:Psychiatric comorbidity differences in male and female adult psychiatric inpatients with

substance use disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 1997 May-Jun ; 38(3): 155-9.

69. Brunette M.F., Drake R.E. : Gender differences in patients with schizophrenia and substance abuse. Compr Psychiatry. 1997 Mar-Apr; 38(2): 109-16.

70. Luthar S.S., Cushing G., Rounsaville B.J.: Gender differences among opioid abusers:pathways to disorder and profiles of psychopathology. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996 Dec 11;43(3): 179-89.

71. Davis D.R., DiNitto D.M.: Gender differences in social and psychological problems of substance abusers: a comparison to nonsubstance abusers. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1996 Apr-

Jun; 28(2): 135-45.

72. Powis B., Griffiths P., Gossop M., Strang J.: The differences between male and female users: community samples of heroin and cocaine users compared. Subst Use

Misuse. 1996 Apr; 31(5): 529-43.

73. Brown T.G., Kokin M., Seraganian P., Shields N.: The role of spouses of substance abusers in treatment: gender differences. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1995 Jul-Sep; 27(3): 223-9. 74. el-Guebaly N.: Alcohol and polysubstance abuse among women. Can J Psychiatry. 1995Mar; 40(2): 73-9.

75. Rossow I.: Suicide among drug addicts in Norway. Addiction. 1994 Dec; 89(12): 1667-73.

76. Gossop M., Griffiths P., Strang J.: Sex differences in patterns of drug taking behaviour. A study at a London community drug team. Br J Psychiatry. 1994 Jan; 164(1): 101-4.

77. Brady K.T., Grice D.E., Dustan L., Randall C.: Gender differences in substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1993 Nov; 150(11): 1707-11.

78. Wallen J.: A comparison of male and female clients in substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992; 9(3): 243-8.

79.Shand F. L., Degenhardt L., Slade T., Nelson E. C.

Sex differences amongst dependent heroin users: Histories, clinical characteristics and predictors of other substance dependence. Addictive Behaviors 36 (2011) 27–36.

80. Bargarli, A. M., Faggiono, F., Amato, L., Salamina, G., Davoli, M., Mathis, F., et al. (2006). VedeTTE, a longitudinal study on effectiveness of treatments for heroin addiction in Italy: Study protocol and characteristics of study population. Substance Use & Misuse, 41(14), 1861−1879.

81. Burns, L., Randall, D., et al. (2009). Opioid agonist pharmacotherapy in New South Wales from 1985 to 2006: Patient characteristics and patterns and predictors of treatment retention. Addiction, 104(8), 1363−1372.

82. Degenhardt, L., Randall, D., Hall, W., Law, M. G., Butler, A., & Burns, L. (2009). Mortality among clients of a State-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: Risk factors and lives saved. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 105, 9−15.

83. Fischer, B., Firestone Cruz, M., & Rehm, J. (2006). Illicit opioid use and its key characteristics: A select overview and evidence from a Canadian multisite cohort of illicit opioid users (OPICAN). Canadian Journal of Psychiatry—Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 51(10), 624−634.

84. Fischer, B., Manzoni, P., & Rehm, J. (2006). Comparing injecting and non-injecting illicit opioid users in a multisite Canadian sample (OPICAN cohort). European Addiction

Research, 12, 230−239.

85. Chiang, S. C., Chan, H. Y., Chang, Y. Y., Sun, H. J., Chen, W. J., & Chen, C. K. (2007). Psychiatric comorbidity andgender difference among treatment-seeking heroin

abusers in Taiwan. Psychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences, 61(1), 105−111.

86. Williamson, A., Darke, S., Ross, J., & Teesson, M. (2007). The effect of baseline cocaine use on treatment outcomes for heroin dependence over 24 months: Findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33 (3), 287−293.

87. Darke, S., Ross, J., Lynskey, M., & Teesson, M. (2004). Attempted suicide among entrants to three treatment modalities for heroin dependence in the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS): Prevalence and risk factors. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 73 (1), 1−10.

88. Darke, S., Ross, J., Mills, K. L., Williamson, A., Havard, A., & Teesson, M. (2007). Patterns of sustained heroin abstinence amongst long-term, dependent heroin users:

36 months findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS).

Addictive Behaviors, 32(9), 1897−1906.

89.Hoda, Z., Kerr, T., Li, K., Montaner, J. S. G., & Wood, E. (2008). Prevalence and correlates of jugular injections among

injection drug users. Drug & Alcohol Review, 27(4), 442−446. 90. Chatham, L. R., Hiller, M. L., Rowan-Szal, G. A., Joe, G. W., & Simpson, D. D. (1999). Gender differences at admission and follow-up in a sample of methadone maintenance clients. Substance Use & Misuse, 34(8), 1137−1165.

91. Darke, S., Ross, J., Teesson, M., & Lynskey, M. (2003). Health service utilization and benzodiazepine use among heroin users: Findings from the Australian Treatment

Outcome Study (ATOS). Addiction, 98(8), 1129−1135.

92. Fletcher, B. W., Broome, K. M., Delany, P. J., Shields, J., & Flynn, P. M. (2003). Patient and program factors in obtaining supportive services in DATOS. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25(3), 165−175.

93. Rehm, J., Frick, U., Hartwig, C., Gutzwiller, F., Gschwend, P., & Uchtenhagen, A. (2005). Mortality in heroin-assisted treatment in Switzerland 1994–2000. Drug & Alcohol

Dependence, 79(2), 137−143.

94. Mills, K. L., Teesson, M., Darke, S., Ross, J., & Lynskey, M. (2004). Young people with heroin dependence: Findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study

(ATOS). Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27(1), 67−73.

95. Darke, S., Ross, J., Williamson, A., Mills, K. L., Havard, A., & Teesson, M. (2007). Patterns and correlates of attempted suicide by heroin users over a 3-year period: findings

from the Australian treatment outcome study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 87(2–3),146−152.

96. Darke, S., & Ross, J. (1997). Polydrug dependence and psychiatric comorbidity among heroin injectors. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 48, 135−141.

97. Darke, S., & Hall, W. (1995). Levels and correlates of polydrug use among heroin users and regular amphetamine users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 39, 231−235.

98. Monga, N., Rehm, J., Fischer, B., Brissette, S., Bruneau, J., & El-Guebaly, N. (2007). Using latent class analysis (LCA) to analyze patterns of drug use in a population of illegal

opioid users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88, 1−8.

99. Conroy, E., Degenhardt, L., Mattick, R. P., & Nelson, E. N. (2009). Child maltreatment as a risk factor for opioid dependence: Comparison of family characteristics and type and severity of child maltreatment with a matched control group. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 343−352.

100. Maloney, E., Degenhardt, L., Darke, S., Mattick, R. P., & Nelson, E. (2007). Suicidal behaviour and associated risk

factors among opioid-dependent individuals: A case–control study. Addiction, 102(12), 1933−1941.

101. Domingo-Salvany A., Brugal M. T., Barrio G., González-Saiz F., Bravo M J.,de la Fuente L. Gender differences in health related quality of life of young heroin users. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8:145.

102. Wilson IB, Cleary PD: Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995, 273:59-65.

103. Zubaran C, Foresti K: Quality of life and substance use: concepts and recent tendencies. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2009, 22:281-286.

104. Puigdollers E, Domingo-Salvany A, Brugal MT, Torrens M, Alvaros J, Castillo C, et al: Characteristics of heroin addicts entering methadone maintenance treatment: quality of life and gender. Subst Use Misuse 2004, 39:1353-1368.

105. Millson P, Challacombe L, Villeneuve PJ, Strike CJ, Fischer B, Myers T, et al: Determinants of health-related quality of life of opiate users at entry to low-threshold methadone programs. Eur Addict Res 2006, 12:74-82.

106. Alonso J, Anto JM, Moreno C: Spanish version of the Nottingham Health Profile: translation and preliminary validity.

Am J Public Health 1990, 80:704-708.

107. Michelson H, Bolund C, Nilsson B, Brandberg Y: Health- related quality of life measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30– reference values from a large sample of Swedish population. Acta Oncol 2000, 39:477-484.

108. Giacomuzzi SM, Riemer Y, Ertl M, Kemmler G, Rossler H, Hinterhuber H, et al: Gender differences in health-related quality of life on admission to a maintenance treatment program. Eur Addict Res 2005, 11:69-75.

109. Astals M, Domingo-Salvany A, Castillo-Buenaventura C, Tato J, Vazquez JM, Martin-Santos R, et al: Impact of substance dependence and dual diagnosis on the quality of life of heroin users seeking treatment. Substance Use & Misuse 2008, 43:612-632.

110. Jarrin I, Geskus R, Bhaskaran K, Prins M, Perez-Hoyos S, Muga R, et al: Gender differences in HIV progression to AIDS and death in industrialized countries: slower disease progression following HIV seroconversion in women. Am J Epidemiol 2008, 168:532-540.

111. Maremmani I, Castrogiovanni P. DAH-RS: Drug addiction history rating scale. Pisa: University Press,1989.

112.Kelly, B.C., Parsons, J.T. 2007. Prescription drug misuse

among club drug-using young adults. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 33 (6): 875-84.

113. Wagner-Servais, D., Erkens, M. 2003. Methadone-related deaths associated with faulty induction procedures. Journal of

Maintenance in the Addictions 2 (3): 57-67.

114. Zador, D.,Sunjic, S. 2000. Deaths in methadone maintenance treatment in New South Wales, Australia 1990-1995. Addiction 95 (1): 77-84.

115. Maremmani, I.; Pacini, M.; Pani, P.P.; Popovic, D.; Romano, A.; Maremmani, A.G.I.; Deltito, J., Perugi, G. 2009. Use of ―street methadone‖ in Italian heroin addicts presenting for opioid agonist treatment. Journal of Addictive Diseases 28 (4): 382-388.

116. Hamilton A., Grella, C. 2009. Gender differences among older heroin users. Journal of Women & Aging, 21(2), 111−124.

117.Hölscher F., Reissner V., Di Furia L., Room R., Schifano F.,Stohler R., Yotsidi V. and Scherbaum N.

Differences between men and women in the course of opiate dependence: is there a telescoping effect? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010 Apr;260(3):235-41.

118. Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, Brady KT. 2010

Substance abuse in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. Jun;33(2):339-55.

119. Eiroá-Orosa FJ, Verthein U, Kuhn S, Lindemann C, Karow A, Haasen C, Reimer 2010 Implication of gender differences in heroin-assisted treatment: results from the German randomized controlled trial .JAm J Addict. Jul-Aug;19(4):312-8.

120. Becker J. B., Monteggia L. M., Perrot-Sinal T.S.,. Romeo R-D, Taylor J. R., Yehuda R., and Bale T.L. Stress and Disease: Is Being Female a Predisposing Factor?The Journal of Neuroscience, October 31, 2007, 27(44):11851-11855;