POLITECNICO DI MILANO

Master of Science in Management Engineering

School of Industrial and Information Engineering

A DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION FRAMEWORK

FOR CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS:

THE CASE OF ITALIAN MUSEUMS

Supervisor: Prof. Deborah Agostino

Master Thesis by

Agostina Balzano

ID: 884499

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Figures Index ... IV Tables Index ... IV Abstract – English ... V Abstract – Italiano ... VI Executive summary ... VII

1. INTRODUCTION ... 15

1.1 Context analysis ... 15

1.1.1 Cultural heritage institutions ... 15

1.1.2 Digital transformation... 16

1.2 Research objectives ... 19

1.3 Methodology and chapter development ... 23

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 24

2.1 Museums ... 24

2.1.1 Definition ... 24

2.1.2 Economic perspective ... 26

2.1.3 Museum’s value chain ... 28

2.1.4 A sector in transformation ... 33

2.2 Digital revolution ... 37

2.2.1 The principles ... 37

2.2.2 Digital transformation in museums ... 40

2.2.3 Contextualization of digital technologies within museums ... 44

2.3 Digital transformation models ... 57

2.3.1 Relevant dimensions ... 58

2.3.2 A model for museums... 62

3. METHODOLOGY ... 65

3.2 Case studies methodology ... 66 4. RESULTS ... 72 4.1 PU1 ... 72 4.2 SS8 ... 74 4.3 AR6 ... 77 4.4 MT2 ... 79 5. DISCUSSION OF RESULTS ... 85 5.1 Digital enablers ... 85 5.2 Common challenges ... 92

5.3 Digital transformation approaches ... 96

6. CONCLUSIONS... 102

6.1 Master Thesis findings ... 102

6.2 Master Thesis contributions ... 107

6.3 Limitations and future research ... 109

Bibliography ... 110

IV

Figures Index

Figure 1: Digital Transformation Model for Cultural Institutions ... X Figure 2: Approaches to the digital transformation and their respective digital enablers ... XII

Figure 3: Segmentation of Italian museums according to the offered digital services. ... 20

Figure 4: Porter’s Value Chain (Porter, 1985) ... 29

Figure 5: The Museum Value Chain (Porter, 2006) ... 29

Figure 6: Nesta’s value chain for cultural institutions (Bakhshi, & Throsby, 2009) ... 31

Figure 7: The adapted museum’s value chain model (Ferraro, 2011) ... 32

Figure 8: Roadmap of digital innovation ... 40

Figure 9: Museum digital pipeline (Lazzaretti, & Sartori, 2016) ... 46

Figure 10: The participatory museum (Simon, 2010) ... 48

Figure 11: Theoretical Digital Transformation Model for Cultural Institutions... 64

Figure 12: Application of the model to case study PU1 ... 74

Figure 13: Application of the model to case study SS8 ... 76

Figure 14: Application of the model to case study AR6 ... 79

Figure 15: Application of the model to case study MT2 ... 83

Figure 16: Validated Digital Transformation Model for Cultural Institutions ... 92

Figure 17: Empirical approaches to the digital transformation ... 98

Figure 18: Characterization of empirical approaches with the digital enablers ... 100

Figure 19: Result from the case studies: empirical approaches to the digital transformation and their respective digital enablers. ... 105

Tables Index

Table 1: Examples of digital technologies applied within museums’ value chain ... 57Table 2: Relevant digital transformation dimensions extracted from the literature review of existent models... 59

Table 3: Case studies’ presentation ... 68

V

Abstract – English

The rise of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) has radically changed the business paradigms of organizations, forcing them to rebalance their strategic vision and operations for remaining competitive. This challenging environment, characterized by cultural, social and technological changes, has impacted on all sectors of the economy, included the cultural heritage one, in which digital technologies have modified the cultural production, distribution and consumption patterns, pushing institutions to reassess their traditional role away from their custodial focus and towards audiences and their experiences.

While embracing a digital transformation can help cultural institutions to further valorize their heritage and enhance the generated value, many entities are uncertain of how to do it. Indeed, literature concentrates on the contextualization of digital technologies within museums, but information regarding the strategic approach to adopt them is limited and dispersed. Since cultural institutions are a vital part of the European economy, it is important to encourage them to innovate and seize the opportunities offered by digitalization. On the basis of these considerations, the present thesis arises with the objective of supporting cultural institutions, and in particular museums, in their digital transformation path by identifying its critical success factors and, additionally, highlighting the most common challenges they should manage. In order to do so, a theoretical framework has been constructed, borrowing insights from existing digital transformation models of the industrial sector. Then, its validation has been done through a qualitative methodology, in which the theoretical model was applied to four case studies of Italian museums.

As a result, the thesis presents the levers of the digital transformation in an integrative model ad hoc for museums, as well as their common challenges. Additionally, deriving from the case studies analysis, four different approaches of museums towards the digital innovation have been identified. These are attractive outcomes from museum practitioners’ point of view since they are tools that can help them in their decision-making process and in consciously managing the innovation. Furthermore, the present work sets future research directions for exploring the possible applications of the proposed framework and approaches on a larger group of museums, on diverse type of cultural institutions, and even beyond the Italian context.

VI

Abstract – Italiano

L’introduzione delle tecnologie dell’informazione e della comunicazione (ICTs in inglese) ha cambiato radicalmente i modelli di business delle varie organizzazioni, obbligandole, per rimanere competitivi, a rivedere la loro visione strategica e la loro operatività. Questa nuova sfida, caratterizzata da cambiamenti culturali, sociale e tecnologici, ha coinvolto tutti i settori dell’economia, incluso quello culturale, nel quale, le tecnologie digitali hanno modificato i modelli di produzione, distribuzione e consumo dei contenuti culturali, spingendo le istituzioni a reinventare il loro ruolo al di là della custodia del patrimonio, ma verso il pubblico e le loro esperienze.

Anche se la trasformazione digitale può aiutare le istituzioni culturali a valorizzare ulteriormente il proprio patrimonio e ad aumentare il valore generato, molte entità sono incerte sul modo di affrontarla. In effetti, la letteratura si concentra sulla contestualizzazione delle tecnologie digitali all’interno dei musei, mentre le informazioni relative all’approccio strategico su come implementarle sono limitate e disperse. Poiché le istituzioni culturali sono una parte vitale dell’economia europea, è importante incoraggiarle a innovare e a cogliere le opportunità offerte dalla digitalizzazione. Sulla base di queste considerazioni, la presente tesi nasce con l’obiettivo di supportare le istituzioni culturali, e in particolare i musei, nel loro percorso di trasformazione digitale, individuando i fattori critici di successo e, inoltre, evidenziando le sfide più comuni che potrebbero dover affrontare. Per fare ciò, si è sviluppato un modello teorico, prendendo in considerazione i modelli di trasformazione digitale già esistenti, ma dedicati al settore industriale. In seguito, la sua validazione è stata fatta attraverso una metodologia qualitativa, in cui il modello teorico è stata applicato a quattro casi di studio di musei italiani.

Di conseguenza, la tesi presenta le leve della trasformazione digitale, oltre alle sue sfide più comuni, in un modello integrativo ad hoc per i musei. Inoltre, dall’analisi dei casi di studio, è stato possibile identificare quattro approcci diversi dei musei verso l’innovazione digitale. Questi risultati sono particolarmente fruibili dal punto di vista dei direttori dei musei poiché sono strumenti che possono aiutali nel loro processo decisionale e nella gestione consapevole dell’innovazione. Inoltre, il presente lavoro evidenzia l’opportunità di esplorare nuove applicazioni del modello proposto su un più ampio campione di musei, su diversi tipi di istituzioni culturali e anche, fuori dal contesto italiano.

VII

Executive summary

As presented in the International Council of Museums’ Statutes (2007):

“A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment.”

Considering this definition, the mission of these cultural institutions can be articulated around three synergic pillars:

• Heritage: this pillar is the fundamental element that characterizes, and counter distinguishes cultural institutions. The focus is set on the conservation and revitalization of this large repository of knowledge.

• Audience: besides the preservation of heritage, museums are responsible of making it available to the public for their education, as well as for ensuring the transmission of culture among societies and across generations.

• Network: lastly, as museums are social institutions, they create relationships with individuals and other organizations, bonding the community and generating networks. Up to now, museums’ efforts have been largely concentrated on the Heritage pillar and thus, on the preservation of cultural heritage, and not on how it is conveyed and communicated to audiences and the community in general. However, the dynamic context of the 21st century is

leading changes that have an impact on the entire society, including on the traditional business models of companies and institutions. In particular, four drivers of change that impact on the cultural sector can be observed (Bakhshi, & Throsby, 2009):

A) Changes in patterns of demand: customers’ spending pattern in cultural activities has a declining trend (Ravanas, 2007) while, on the other hand, the expenditure on online leisure activities is every time higher. This change in customers’ habits implies a great challenge for cultural institutions, which are presented a new type of audience willing to co-produce and personalize its own experiences.

B) Changes in unearned revenue sources: the increased pressure on governmental budgets and the reduction of public spending has led to a reduction of funds destined to cultural institutions and the terms on which they are given. As a result, museums are forced to operate in an even more limited cost-revenue scenario.

VIII C) Changes in technology: ICTs have transformed all social aspects, as well as the way in which organizations operate. The impact, and thus opportunities, can be observed throughout the museum: in the internal organization (production), in the communication with audiences (distribution), and in the way visitors interact with the cultural organization and its heritage (consumption) (European Commission, 2016). D) Changing concepts of value creation: all of the aforementioned drivers of change

impact in cultural institutions’ environment, affecting the way in which value is perceived and delivered (Bashkhi, & Throsby, 2009). The most relevant aspect is the emphasis that is put on what customers value and expect from museums.

Thus, the fast-moving context of the 21st century is characterized by demographic shifts, changing customer expectations and continual technological innovation (Tassini, Gu, & Aris, 2016). In this challenging environment, for museums to remain relevant to audiences and ensure their sustainability, they need to evolve according to visitors’ expectations. This involves recalibrating their focus from objects to users by becoming more interactive, participatory and democratic in their relationship with visitors. As a result of this paradigm shift, the pillars Audience and Network acquire an increasing relevance, while Heritage still maintains as the distinctive element of cultural institutions.

In this context, digital technologies present as strategic tools to advance the organization’s mission while allowing it to create a differential and valuable offering. The applications of these new technologies are numerous and can support cultural institutions along their three synergic pillars:

• Regarding Heritage: improving preservation methods, as well as creating digital heritage which can be valorized through different channels.

• Regarding Audience: increasing on-site and online user engagement, aligning the museal offering to visitors’ expectations.

• Regarding Network: generating a museal community through active marketing and digital channels.

• Finally, considering a more transversal perspective, the employment of digital technologies can lead to the optimization of institutions’ internal processes.

Thus, embracing a digital transformation, and so integrating technology and innovation at the core of their strategy, will allow institutions to further valorize their heritage and improve the value proposition for their audiences, ensuring their long-term sustainability.

IX Nonetheless, many entities are uncertain regarding how to approach such transformation. Indeed, the available literature on museums and their digital transformation has concentrated on the possible applications of new technologies for achieving a precise objective. In particular, the most repeated issues concern the utilization of digital communication and marketing instruments for approaching visitors; of on-site digital tools for improving the museal experience; and lastly, of digitizing technologies for the long-term preservation of artworks. Thus, there is a lack of material determining complete digital strategies specifically for museums, meaning: how to strategically approach the transformation, which are the key necessary resources, which are the most common barriers they may encounter... These are all issues which could help institutions mitigate their uncertainty on how to act, and yet this type of information is scarce and dispersed among different sources and authors. On the contrary, when referring to other industry fields (especially manufacturing), the literature on digital transformation models has proven to be extensive.

According to the European Commission (2014), cultural institutions are a vital part of the economy and thus, it is important to encourage them to innovate and seize the opportunities offered by digitalization. On the basis of these considerations, the present thesis arises with the objective of supporting cultural institutions, and in particular museums, in their digital transformation path by identifying its critical success factors and, additionally, highlighting the most common challenges they should manage. These objectives can translate into the following research questions:

RQ 1. Which are the main factors enabling museums to achieve an effective digital transformation?

RQ 2. Which factors or conditions represent obstacles for museums in their digital transformation path?

For investigating these aspects, an integrative theoretical framework has been constructed ad hoc for museums, extracting relevant dimensions from existent digital transformation models of the manufacturing area and making some considerations for the cultural sector. Then, in order to validate the model, it has been tested on Italian museums because of two reasons: on one side, Italy is recognized worldwide for its incalculable cultural heritage and, on the other, it is an active environment where institutions are willing to innovate and progress in the digital transformation and thus, are strengthening their efforts in that direction (Osservatorio Innovazione Digitale nei Beni e Attività Culturali, 2018). The methodology applied was purely

X qualitative and can be defined as a multiple case studies analysis. In particular, direct semi-structured interviews have been conducted with four Italian museums of diverse characteristics to analyze their corresponding digital projects and draw empirical evidence from them.

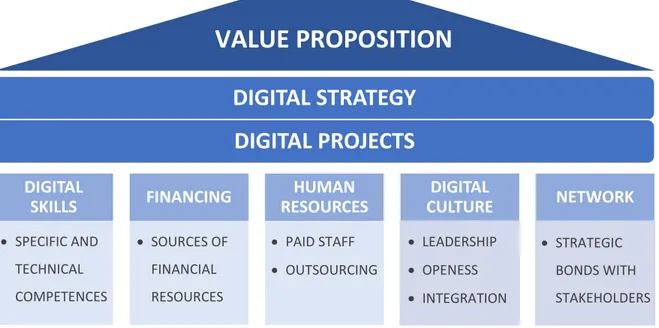

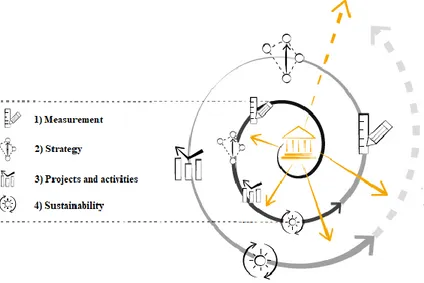

The first result of the conducted analysis regards the validation of the Digital Transformation Model for Cultural Institutions, depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Digital Transformation Model for Cultural Institutions

The starting point is the Value Proposition, which will guide the adoption of digital technologies within the institution. The precise objectives institutions expect to achieve should be clearly defined in the Digital Strategy to guarantee its alignment with the organizational strategy and avoid isolated initiatives. Then, the latter is implemented through diverse Digital Projects, which count with five levers for their management and execution:

1) Digital skills: to derive value from digital technologies and manage internally the transformation, museums’ staff members should develop an additional set of technology-related competences such as managing information resources and administering content management systems…

2) Human resources: the team who deals with the execution and development of the project is a fundamental resource. Depending on the level of in-house technological competences, museums will rely on internal employees, or otherwise, turn to outsourcing. DIGITAL SKILLS FINANCING HUMAN RESOURCES DIGITAL CULTURE NETWORK • SPECIFIC AND TECHNICAL COMPETENCES • SOURCES OF FINANCIAL RESOURCES • PAID STAFF • OUTSOURCING • LEADERSHIP • OPENESS • INTEGRATION • STRATEGIC BONDS WITH STAKEHOLDERS

DIGITAL STRATEGY

DIGITAL PROJECTS

VALUE PROPOSITION

XI 3) Digital culture and leadership: the top-management has the key responsibility of leading the entire institution and communicating the vision set by the digital strategy. Furthermore, advancing in the right direction will require the correct organizational culture, characterized by openness to innovation, interdisciplinary work and cooperation between departments and roles.

4) Network: the creation of a network with its surrounding ecosystem, including private and public entities, will allow museums to learn from each other’s experiences and spread good practices. Furthermore, through more formal partnerships, museums can gain accessibility to knowledge and resources for the development of their projects. 5) Financing: the availability of financial resources is fundamental for the digital

transformation since organizational changes do not happen without investment. The second finding of the present thesis concerns the identification of common challenges cultural institutions may encounter in their digital transformation path, and which should be carefully managed for avoiding them compromising its outcome:

A) Missing skills: 21st-century institutions need staff members who understand, not only museums’ information (cultural content), but also the information technology behind it. While training staff members may be challenging due to their diverse backgrounds, the investment is necessary for managing internally the transformation and being able to make crucial technology-related decisions.

B) Organizational inertia: when facing transformations, internal resistance may appear and compromise its progress (especially from older people or cultural professionals devoted to historical heritage). Since the human resources and their collaboration are fundamental for the introduction of digital technologies, institutions may approach this challenge by embracing change management practices.

C) Resource constraints: the restricted resource availability of many museums may create a challenging environment for innovation. In particular, the constraints could translate in limited in-house staff time and limited funding. Thus, for ensuring the sustainability of a digital project, museum directors should assess their available resources against the expected required ones for its entire duration.

D) Cultural content management:

i. The first issue concerns the need to create and transmit content that is enjoyable and public-friendly, but that simultaneously maintains curatorial and

XII educational standards. It is about mastering the digital storytelling and being able to interpret cultural content in ways that visitors can relate to.

ii. Then, the second aspect regards the intellectual property rights of collections and thus, the publishing restrictions of their digitized versions, with which museums should comply (especially given the broad distribution and virality of the Internet).

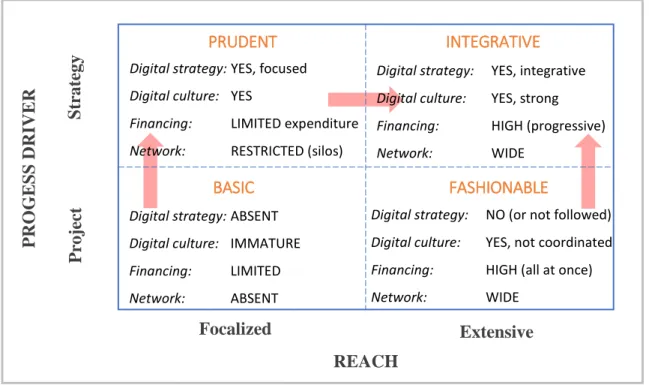

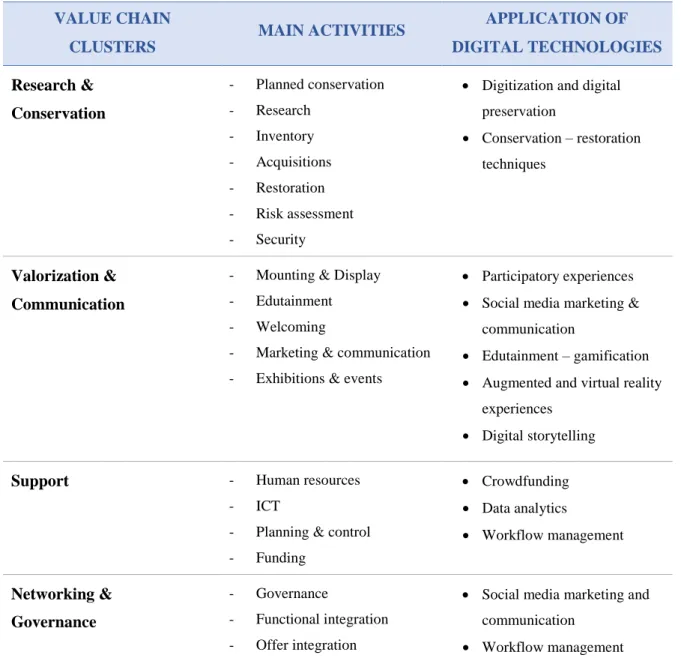

Finally, the third result obtained from the case studies’ analysis is the recognition of four different approaches to the digital transformation, which can be identified according to the Reach” of the transformation within the institution and its “Progress driver”. Additionally, as observed in Figure 2, each one of the approaches can be characterized with the digital enablers (except from “Digital skills” and “Human Resources” which will depend on the particular institution and thus, cannot be generalized).

Figure 2: Approaches to the digital transformation and their respective digital enablers

Integrative approach: these museums share a strong vision and support of the digital transformation which is deployed into a series of valuable digital initiatives across its many sectors, presenting a unified front. This quadrant is aligned with the theoretical approach that identifies a strategical and linear sequence for the adoption of new technologies.

REACH P RO G E S S DR IVER Focalized Extensive S tr ate gy P ro je ct PRUDENT BASIC INTEGRATIVE FASHIONABLE Digital strategy: YES, focused

Digital culture: YES

Financing: LIMITED expenditure Network: RESTRICTED (silos)

Digital strategy: ABSENT Digital culture: IMMATURE Financing: LIMITED Network: ABSENT

Digital strategy: YES, integrative Digital culture: YES, strong Financing: HIGH (progressive) Network: WIDE

Digital strategy: NO (or not followed) Digital culture: YES, not coordinated Financing: HIGH (all at once) Network: WIDE

XIII Prudent approach: the digital strategy, supported by leadership and digital culture, exists but is focalized on just few aspects of the museum. This denotes a prudent and sequential approach, which consists in testing new technologies within a certain sector and, if the results are positive, then move forward with the investment in other areas.

Fashionable approach: museums following this approach are willing to rapidly advance digital innovation within the current dynamic context and thus, implement attractive and expensive digital features in several areas, but that do not always create value collectively since they lack an integrative vision.

Basic approach: institutions in this category are unaware or skeptical of the possibilities offered by digital technologies and so, they present an immature digital culture. Without a clear vision, their approach to the digital transformation is through experimentation projects of medium-limited reach to explore how digital tools could work within the museum.

Furthermore, considering the matrix under a dynamic perspective, and setting as objective the achievement of the upper-right quadrant, it has been possible to determine the evolution path of each one of the approaches according to their characteristics (indicated with red arrows in Figure 2).

On the basis of the presented results and, given the lack of academic material determining complete digital strategies specifically for museums, the present Master Thesis has contributed to a part of the literature which has not been previously explored completely and with big room for development. The created digital transformation model was created ad hoc for museums and, furthermore, adopts an integrative approach, unlike the most usual one of treating transformation aspects singularly. Parallelly, the identification of the common challenges has also been done according to museums’ characteristics and their particular operating context. Finally, through the conducted case studies, the Master Thesis has made an additional contribution to the academic environment by providing empirical evidence on museums’ approaches to the digital transformation.

On the other side, the present dissertation has practical implications for the museum management and practitioners. In the first place, the created framework serves as a tool which museums’ directors can use for implementing digital technologies successfully. It has been created to specifically support the strategic decision-making process of digital innovation and an “Integrative” type of approach. In this way, the thesis has intended to reduce the number of institutions which approach the transformation focused on technology, rather than on strategic

XIV objectives. Furthermore, if museum practitioners are aware of the common challenges that may present, there will be a lower probability of overseeing these factors and thus, of compromising the results of the innovation. In the second place, providing museums a guidance tool is a way to help them pursue their digital agendas, as established by the European Commission in the communication entitled “Towards an Integrated Approach to Cultural Heritage for Europe” (2014). Finally, museums can use the created framework and matrix as benchmarking tools for determining the relative position of the museum (its strengths and weaknesses) compared to other institutions, as well as for identifying good management practices to follow.

The limitations of the present thesis reside mainly in the chosen methodology. The purely qualitative analysis may have provided some results subject to the interpretation of the writer. As a result, the case study analysis in itself is unique and would be extremely difficult to replicate. Nonetheless, the authenticity and validity of the obtained results is ensured by a triangulation between the empirical data and the review of the academic literature.

In the last place, considering the findings and limitations of the Master Thesis, two directions for future research can be identified. The first regards enlarging the number of museums used for the case studies: a larger sample would have resulted in a more robust validation of the created framework, as well as of the matrix depicting the empirical approaches to the digital transformation. Then, the second direction concerns expanding the application boundaries of the created framework and matrix. This would imply testing them on museums outside of the Italian context and, even, explore if they are applicable as well for other entities of the cultural sector such as archives, theaters and libraries.

15

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Context analysis

1.1.1 Cultural heritage institutions

Cultural heritage is the legacy of physical artefacts and intangible attributes of society that are inherited from past generations, maintained in the present and bestowed for the benefit of future generations (UNESCO). The cultural heritage is a shared wealth, a legacy belonging to all humankind which represents an irreplaceable source of knowledge.

Correspondently, cultural heritage institutions are engaged with the acknowledged mission of preserving, studying and enhancing, and making accessible to society, for its instruction and enjoyment, the cultural property. As a result, these institutions are important actors in the transmission of culture among societies and across generations, an essential facet of human development according to UNESCO. Considering the stated mission of cultural institutions, their strategic objectives can be defined around three main synergic pillars:

• Heritage: this pillar is the fundamental element that characterizes, and counter distinguishes cultural institutions. Heritage is at the center of such organizations and it is their main object of analysis. In particular, the focus is set on its conservation, revitalization and physical and cultural dissemination.

• Audience: besides the technical aspect of conservation and maintenance of heritage, cultural institutions are responsible for making available to the public this large repository of knowledge. In order to do so, institutions promote activities that favor an active interaction and engagement of the society, and that are aimed at informing and educating citizens on associated aspects of culture, history, science and the environment.

• Network: finally, cultural institutions create multiple social benefits, which include customer value, community outreach, and public service (Kotler N., Kotler P., & Kotler W., 2008). As a consequence, a strategic objective is to create relationships through physical or digital networks with individuals, other institutions and the entire community.

Regarding the classification of cultural institutions, the Italian law1 includes under such definition the following entities: museums, libraries, archives, archeological sites and parks,

16 and monumental sites. According to the ISTAT (2016), in 2015 the Italian cultural heritage sector reached 110,4 million visitors and a total of 4.976 institutions divided as following: the majority (83,6%) was represented by museums, galleries and collections; then, 5,6% were archeological reserves; and the remaining 10.8% were monuments or monumental sites.

1.1.2 Digital transformation

In the Digital Age, the world is changing faster than ever, and society is living a moment of profound disruption. The rise of new digital technologies and its application to all aspects of everyday life is challenging the traditional business paradigms of companies and institutions while new ones are emerging. These innovative models concentrate on seamlessly integrating two fundamental factors that are people and technology, by embracing the path of digital transformation. As stated by the vice president of IBM, to succeed in such enterprise companies should focus on two complementary activities directly related to the fundamental factors previously mentioned: one is reshaping customer value propositions and the other is transforming their operations by using digital technologies for greater customer interaction and collaboration (Berman, 2012).

These changes associated with digital innovation have been steadily increasing since the beginning of the 21st century and are flowing into what can be defined as a new industrial

revolution (Blanchet et al., 2014). From the first industrial revolution which allowed the mechanization through steam power, to the mass production and assembly lines using electricity in the second, the fourth industrial revolution will take what was started in the third one (“The digital revolution”) with the adoption of computers and automation and will enhance it with smart and autonomous systems fueled by data and machine learning (Marr, 2018). The Digital Revolution, in the 1970s, introduced technological breakthroughs that have revolutionized communications and the spread of information. It was in this context that the Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) arose: a broad term encompassing cellular networks, satellite communication and broadcasting media, among others. Now, the further transition towards an integrated network is so compelling that its application in the manufacturing sector has led to the creation of the German concept of Industrie 4.0 (commonly known in English as Industry 4.0). This bigger notion emphasizes the idea of consistent digitalization and linking of all the productive units in an economy to reach a fully integrated, automated and optimized flow, with greater efficiencies and changed relationships with customers – as well as between human and machine (Rüßmann et al., 2015).

17 Industry 4.0 and ICTs have changed forever the way information is created, managed, archived and accessed (Abd Manaf, 2007). The impact of such revolution is not only witnessed in manufacturing, but on all sectors of the economy and the cultural heritage one is no exception. Digital technology has changed the way that we engage with arts and culture, as it has with many other areas of life (Runacres, & Bakhshi, 2017), impacting on the entire value chain. It has brought changes inside the organization – production-, in the cultural heritage institution’s communication with the public – distribution-, and in the way the public interacts with the institution and its contents – consumption (European Commission, 2016). To mention just one aspect of this transformation it is possible to quote Sree Sreenivasan, Chief Digital Officer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) in New York from 2013 to 2016, who said “Our competition is Netflix and Candy Crush, not other museums” (Shu, 2015). Despite having one of the greatest art collections and being one of the most visited museums, the Met faces the same uncertainty as any other institution. This statement recognizes cultural and demographic changes generated by the digital age that represent a new operating environment for the entire cultural sector.

To remain competitive in today’s fast changing era, every organization must find new and creative ways to “stay in the game” (Abd Manaf, 2007). The correct approach is to assume an adaptive behavior to the new environment; to become relevant, resilient and responsive to digital cultural changes. Institutions that perceive digital technology as a strategic imperative, rather than simply as a tool, are more likely to take full advantage of the digital disruption and ensure their long-term sustainability (Nash et al., 2016). Turning to the Met, this museum represents an excellent case of adoption of a digital strategy through the creation of an independent digital department that permeates the entire organization, and through investments in technologies to make the museum experience more interactive.

The relevant issue is seeking innovative ways to use digital technologies as strategic tools to advance the organization’s mission and strategy (Tassini, Gu, & Aris, 2016). This means that leveraging on digital innovation, cultural institutions can further valorize their heritage and increase the value generated for individuals and the entire community. The opportunities digital technologies present are numerous as they can support and facilitate cultural institutions in reaching the three strategic pillars identified in the previous section. In particular:

• Regarding Heritage: Improvement of preservation methods, as well as creation and valorization of digital heritage.

18 Cultural institutions adopt digital preservation techniques, which focus on the means of selecting, collecting, transforming from analogue to digital, storing and organizing information in digital form and then making it available for searching, retrieval and processing via communication networks (Abd Manaf, 2007). The aim is to guarantee the conservation of the knowledge embedded within cultural heritage for future generations, as well as the creation of digital collections that can democratize the access to culture. Equally, digital technologies provide novel and improved methods for restoring physical cultural assets.

• Regarding Audience: Increase of on-site and online user engagement, aligning the museal offering to visitors’ expectations.

Digital technologies have a positive impact in relation to audiences for they allow cultural institutions to expand: the audience breath – to reach different and more diverse audiences; the audience width – to reach a larger audience; and the audience depth – to engage more with current audiences. All in all, digital tools allow cultural institutions to become “experience providers”, rather than simple heritage guardians, and to customize such experience through a strong understanding of the visitors’ needs and preferences. Digital technologies have created a paradigm shift within cultural institution from being object-centered to user-object-centered. Apart from the preservation of heritage, now the focus is set on its distribution and consumption. The final result is the development of a long-term relationship with the audience that extends beyond the walls of the cultural institution and the duration of an exhibition.

• Regarding Network: Generation of a museal community through active marketing and digital channels.

New information and communication technologies allow cultural institutions to connect with audiences, cultural professionals, similar institutions and the entire web in real time; i.e. to be in contact with the community. The benefits range from active and dedicated marketing actions, to the organization of cultural initiatives and generation of crowdfunding and fundraising platforms.

• Finally, considering a more transversal perspective, the employment of digital technologies can lead to the optimization of institutions’ internal processes (Accountability & Control, Human Resources, Administration, and so on…).

19 As a consequence, the digital transformation is much more than publishing an appealing website, providing access to collections online or digitizing the on-site experience. To seize the opportunities that the digital revolution presents, institutions must employ the technologies throughout the organization to drive performance and efficiencies. Digital should be a leverage to increase the generated value. This includes using digital tools to analyze audience data, improve and develop delivery channels, create new content and improve operational efficiency (Tassini, Gu, & Aris, 2016).

To summarize, cultural institutions are subject to a paradigm shift in a world disrupted by the digital revolution. Facing fundamental demographic shifts, changing customer expectations and continual technological innovation (Tassini, Gu, & Aris, 2016), transformation is the term that better suits the cultural heritage sector in the 21st century. Embracing the digital transformation, and so integrating technology and innovation at the core of their strategy, will allow institutions to seize the numerous opportunities that come along and improve the value generated to the entire community.

1.2 Research objectives

The previous chapter has emphasized the relevance of the digital transformation within cultural heritage institutions in the fast-moving and changing environment of the 21st century. This thesis will explore the dimensions of such transformation with a concrete focus on Italian museums. The decision to delimit the research becomes inevitable in a sector comprised of a broad group of sub sectors delivering a diverse range of services and functions (Museums Association, 2008). However, the selection neither of Italy nor of museums as study objects is arbitrary.

Italy is a country recognized for its cultural heritage, both physical and intangible. Its culture is steeped in the arts, architecture and music. Home of the Roman Empire and a major center of the Renaissance, culture on the Italian peninsula has flourished for centuries (Zimmermann, 2017). The result is a country with an incalculable heritage to be preserved and diffused. In the last ISTAT survey “Indagine sui musei e le istituzioni similari” (2015), Italy has been defined as a diffused museum with a density of 1,7 museums or similar institutions every 100 km2. Furthermore, it is the country with the highest number of UNESCO heritage sites in the world. Regarding the choice of focusing on museums, numbers can provide a fair justification. Of the 4.976 cultural institutions in Italy, 4.158 (83,5%) are museums and galleries while the remaining 16.5% is distributed among archeological sites and monuments (ISTAT, 2016).

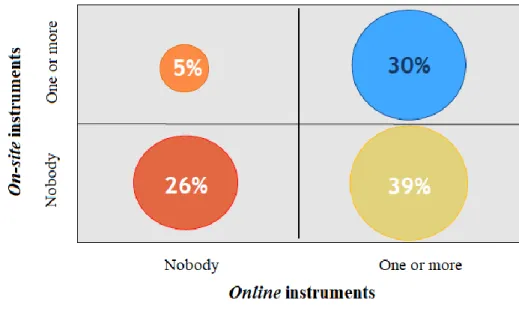

20 Correspondently, considering the 110,4 million visits to Italian cultural institutions in 2015, more than 50% (59,2 million) were to museums. As a result, the Italian landscape and its museums seem to be a precious opportunity for conducting a research on cultural heritage. As it was previously discussed, digital technologies can provide a large number of opportunities to cultural institutions which ultimately can result in an enhancement of the economic and social value generated. However, from case studies performed by the Osservatorio Innovazione Digitale nei Beni e Attività Culturali of Politecnico di Milano, it results that Italian museums are just at the beginning of their digital transformation process. There are still few cultural institutions which use the new instruments of digital information and communication in all its potential. The 2015 ISTAT survey shows how the 26% of almost five thousand Italian museums does not offer to the public any type of digital service neither of support to their on-site visit (app, QR code, Wi-Fi, audio guides) nor online (website, social media accounts, online ticketing). As shown in Figure 3, just 30% of the museums offer at least one digital service on-site and one online, but the percentage reduces to 11% if considered museums that provide at least two (Osservatorio Innovazione Digitale nei Beni e Attività Culturali, 2018). Indeed, the number of institutions in Italy which follow a concrete innovation plan is limited.

Figure 3: Segmentation of Italian museums according to the offered digital services. Total: 4.976 institutions (Osservatorio Innovazione Digitale nei Beni e Attività Culturale, 2018)

On the other hand, in the communication entitled “Towards an Integrated Approach to Cultural Heritage for Europe” (2014), the European Commission defines the cultural heritage sector as a sector in transformation motivated by urbanization, globalization and technological changes.

21 Museums are recognized as important forces in the economy which should reinvent themselves to seize the opportunities this new environment presents. Digitalization and online accessibility of cultural content shake up traditional models, transform value chains and call for new approaches to the cultural and artistic heritage (European Commission, 2014). In this context, the European Commission addresses the social and economic value of museums, claiming that technology can significantly enhance it: digitized cultural material can be used to enhance visitors’ experience, develop educational content, documentaries, tourism applications and games (European Commission, 2014). Therefore, to strengthen Europe’s position in the field of cultural heritage the Commission recognizes as a need to:

• encourage the modernization of the heritage sector, raising awareness and engaging new audiences,

• apply a strategic approach to research and innovation and • seize the opportunities offered by digitalization.

However, in this particular communication the European Commission does not provide concrete guidelines addressed to cultural institutions on how to achieve the three aforementioned points and which are the resources to be employed. Indeed, analyzing the existent literature it can be observed that the large majority of it follows the same approach. The focus is set, instead, on the possible applications digital tools could have within museums. The most repeated issue refers to the utilization of digital technologies for improving visitors’ satisfaction and increasing their participation. Examples include immersive on-site experiences or digital tours. In the same line, the literature tackles the use of digital tools for communicating with visitors and enlarging their number through, for example, attractive websites and social media. Another common issue to many papers concerns the utilization of digitization2

technologies for long term preservation; an issue widely diffused probably considering the relevance of this action for cultural institutions.

Summarizing, literature concentrates in the contextualization of digital technologies within museums by providing concrete application examples and for achieving a particular target (such as improving customer satisfaction, enlarging the visitors’ base or preserving heritage…). However, there is a lack of material addressed to cultural institutions which guides them through their digital transformation, i.e. on how the organization should strategically approach

2 Digitization refers to the means of selecting, collecting, transforming from analogue to digital, storage and

organization of information in digital form and the making it available for searching, retrieval and processing via communication networks (Abd Manaf, 2007).

22 such transformation in the first place. Information is very limited and dispersed regarding how to adopt a digital strategy, which are the key necessary resources, and which are the most common barriers museums may encounter. To engage in digital transformation, cultural institutions need a framework to guide their analysis, their strategy and their activity planning. Indeed, when analyzing other sectors in the economy, specially manufacturing, the number of theoretical frameworks and models guiding digital transformation is extensive. Considering the existent gap, the present thesis arises to support cultural heritage institutions, in particular museums, along their digital transformation path by:

• identifying the critical dimensions that drive such transformation,

• and understanding how these dimensions should be leveraged to achieve a successful transformation.

These objectives can be translated in the following research questions:

RQ 1. Which are the main factors enabling museums to achieve an effective digital transformation?

The first research question aims at identifying which are the digital enablers of museums. Digital enablers are the pillars upon which technological investments are sustained: they are the levers enabling digital strategies and digital transformation projects. In order to properly identify them, there is the need to adopt a holistic perspective that goes beyond the evident technological levers. Although IT resources are critical and foundational factors required in any digital transformation, by no means they can stand alone. For example, without skilled personal it is not possible to take advantage of what new technologies can bring (Yoo, Wysocki, & Cumberland, 2018). A digital transformation is a much more extensive issue which involves the entire organization and implies the coordination of several key elements. The matter is to clearly identify these critical success factors and determine how they should be leveraged. RQ 2. Which factors or conditions represent obstacles for museums in their digital transformation path?

Along with the identification of the digital enablers comes, as well, the recognition of the main barriers to the adoption of digital technologies. Such factors represent important challenges for organizations which, if overlooked, could compromise the achievement of a successful digital transformation.

23 The presented research questions complement each other by supporting cultural institutions along their digital transformation in a distinctive way. While RQ 1 verifies the necessary resources for implementing a digital strategy, RQ 2 describes the possible challenges institutions may encounter along the way. Both aspects are relevant and represent a source of knowledge for cultural institutions, which may determine the success or the failure of their transformation. In order to deal with the research questions, a theoretical framework has been created. The following section describes in a more detailed way the methodology adopted for this thesis and how the chapters are developed.

1.3 Methodology and chapter development

To begin with, in Chapter 2, an analysis of the existent literature has been performed for building knowledge on the two aspects under analysis: museums and digital technologies. Initially the topics are treated separately for introducing them properly, but then they are combined for approaching the impact the digital revolution is having on museums. Following, to deal with the research questions and the literature gap, a theoretical model for cultural institutions is created. For that purpose, the last part of Chapter 2 consists in the review of the digital transformation models available for other sectors of the economy. Some critical dimensions emerging from this analysis are included in the elaborated framework, along with other elements which belong exclusively to the heritage sector. To validate such model, interviews are carried out with four Italian museums on specific digital projects they have developed (or are developing). Italian museums can provide many insights on digital transformation and be a great setting for validating the model because of the efforts they are making to overcome their digital laggardness. In this sense, the Italian sector is an active and moving environment. The description of the selected organizations and the methodology employed for conducting the interviews is presented in Chapter 3. Following, Chapter 4 presents the results of the multiple case studies, which are thus analyzed critically in Chapter 5 for obtaining empirical evidences. Finally, Chapter 6 concludes with the respective conclusions, which present the Master Thesis’s findings, its academic and managerial implications and, finally, considering the limitations of the work, some outlooks for future research.

24

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Museums

2.1.1 Definition

To begin with, a clear definition and contextualization of museums is required since they represent the object of study of the present thesis. With reference to this subject, the professional definition of museum most widely recognized nowadays is provided by the International Council of Museums (ICOM). The ICOM is an international, non-governmental organization made of museums and museum professionals which is committed to the research, conservation, continuation and communication to society of the world’s natural and cultural heritage. In addition, it establishes professional and ethical standards for museum activities. The ICOM is an undisputed reference since it is the only global organization in the museum field: it counts with 40.000 professionals over 141 countries.

Consequently, as presented in the ICOM’s Statutes of 2007:

“A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment.”

The museum is a permanent institution, meaning a physical place created by man to maintain a relationship with reality. This relationship is defined by the principal functions inherent to any museum: acquisition, conservation, research, communication and exhibition of collections. Collections can be defined as “the collected objects of a museum, acquired and preserved because of their potential value as examples, as reference material, or as objects of aesthetic or educational importance (Burcaw, 1997)” (Desvallées, & Mairesse, 2009). These objects are part of the world’s natural and cultural heritage and may be of tangible or intangible character (ICOM, 2004). However, the incorporation of the intangible heritage, such as testimonies, to the current (2007) definition of museums is a novel aspect. The previous definition, dating back to 1974, has been used as a term of reference for over thirty years and did not contain any reference to intangibility.

“A museum is a non-profit making, permanent institution in the service of society and of its development, and open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates

25 and exhibits, for purposes of study, education and enjoyment, material evidence of people and their environment.” (ICOM Statutes, 1974).

A possible classification of museums can be done by analyzing the character of their contents or collections. Under this category, UNESCO groups them as follows:

a. Fine Arts Museums: collect and preserve aesthetic heritage of man’s creative genius, such as paintings, sculptures, architecture and engravings, among others (Goode, 1896). b. Decorative Arts Museums: contain artistic works of decorative nature.

c. Contemporary Art Museums: contain art created during the 20th and 21st centuries. d. Museum-House Museums: are located in the birthplace or residence of a famous

person.

e. Archeological Museums: contain heritage with historical and/or artistic value from archeological excavations or discoveries.

f. On-site Museums: are created by turning certain historical locations into museums. g. Historical Museums: preserve heritage associated with events in the history of

individuals or nations.

h. Anthropological Museums: include heritage illustrating the natural history of man, his geographical distribution, his organization in tribes and the origins of arts, industries and customs.

i. Natural Science Museums: illustrate phenomena of nature – belonging to the animal, vegetable and mineral kingdoms – and whatever illustrates their origins, function and structure.

j. Science and technological Museums: contain heritage that is representative of the evolution of history, science and technology.

k. Specialized Museums: concentrate on a particular area of cultural heritage that is not covered in any other category.

l. General Museums: can be identified by more than one of the aforementioned categories.

Physical and intangible collections are at the heart of cultural heritage institutions and are their main capital. Indeed, the value of the cultural sector lies in the quality and diversity of the collections (European Commission, 2016). However, the value is also on how they are disseminated and experienced by society who may be changed and transformed by them (European Commission, 2016). This statement recognizes society and the social value generated as key elements for cultural institutions. These notions are central to the any current

26 definition of “museum” and are at the core of their operations: “in the service of society and its development”. In this sense, museums are responsible for making cultural heritage, and all the knowledge embodied in it, available to the community. Without the distribution and public enjoyment of the cultural heritage it holds, part of the museum’s role would be incomplete. This is because, apart from looking after the world’s cultural property, museums interpret it to the public (ICOM, 2004). Museums have been mainly created to increase the cultural and educational level of the population (OECD, 2017); they are social institutions.

Nowadays, with the advent of digital technologies, the relationship between museums and the community is acquiring an increasing relevance. The digital has infiltrated and transformed all aspects of social life and cultural heritage institutions, as social institutions, are part of these changes (European Commission, 2016). In this context, the audience does not require from museums only an educational visit but demands an experience. As a result, cultural institutions are forced to re-define themselves and transform from being just heritage guardians to also experience providers. This means, becoming more interactive, participatory and democratic in their relationship with their visitors and in enhancing their public engagement agendas. In other words, museums are experiencing a paradigm shift from being object-centered to user-centered. This aspect is one of fundamental relevance to the present thesis and so will be discussed in extension further on.

2.1.2 Economic perspective

This section is dedicated to a brief economic analysis of cultural heritage institutions, with the final goal of further modelling and presenting their operating scenario.

Apart from the main role of heritage preservation, cultural institutions can focus on pursuing different objectives - some couched in artistic and creative goals, some in terms of audience engagement, and others related to their pubic and social impact. This multiplicity of objectives is mirrored in the heterogeneity of observed financial structures (Bakhshi, & Throsby, 2009). Such structures differ according to the source of museums’ funds, which may be from the public sector, from private sources or generated through the museum’s own activities. This last element includes additional incomes from admission charges, the gift shop, or food service, among others (ICOM, 2004). Therefore, the particular combination of the three mentioned fund sources determines the financial structure of each institution. This could result in difficulties when trying to model in a general sense the economic behavior of cultural institutions. However, as presented in the previous section, museums are by definition non-profit

27 institutions. As a result, it is possible to apply the basic theory of not-for-profit firms to cultural institutions when performing an economic analysis of these institutions (Throsby, 2001). As non-profit organizations, the essential purpose of cultural institutions is not one of maximizing shareholders’ value in the direct financial sense (Bakhshi, & Throsby, 2009). Instead, the value they generate serves a larger social purpose. As a matter of fact, nowadays museums are encountering a growing need to prove the value they contribute to generate and spread to the society (Bollo, 2013). However, the study of how to measure it presents several difficulties because of its multifaceted character. In order to highlight the multidimensionality of the value generated by museums, the Netherlands Museums Association has identified five values (DSP-groep, 2011) that together make up the social significance of these institutions (Bollo, 2013):

• Collection Value: is at the core of a museum’s existence and comprises the values related to collection, conservation and exhibition activities.

• Connecting Value: depends on the museum’s capability to act as a networker and mediator between different groups in society (giving consistency to current topics and issues through relevant and meaningful contexts) and to become a platform for communication and debates.

• Education Value: lies in the museum’s ability to propose to audiences as a learning environment.

• Experience Value: is related to the museum’s capacity to provide opportunities for enjoyment and experience through which people can be stimulated both physically and intellectually.

• Economic Value: depends on the museum’s contribution to the local economy: the number of tourists they attract, the jobs they create, the capital represented by volunteers…

These five points underline how, clearly, not all of the value generated by museums can be fully captured by the economic value. There are specific characteristics of the cultural value which cannot be reduced to a monetary form (Throsby, 2001).

Analyzing the cost and revenue conditions in which the aforementioned value is generated, non-profit organizations have peculiar characteristics. Generally, they sustain high fixed costs in comparison to the variable costs, a relatively low level of demand and limited funding. This can be justified with the observed decrease of public budgets, as well as, of participation in

28 traditional cultural activities (European Commission, 2014). Consequently, the objective function of museums could be described as involving the joint maximization of the level of output and its quality, subject to a break-even budget constraint (Bakhshi, & Throsby, 2009). The “level of output” concerns access objectives, i.e. attracting the largest number of visitors as possible; while “quality” refers to artistic/curatorial quality standards and so offering the audience valuable collections. These objectives are pursued analyzing the trade-off with costs and so trying to achieve the required balance with the budget.

The presented model, adapted to cultural institutions from non-profit firms, represents in a general sense how museums operate financially. It is worth highlighting the financial challenges they face due to high costs and, generally, low incomes. This situation may then change according to the particular objectives of each institution and their particular contexts.

2.1.3 Museum’s value chain

In the previous section, a description of the multifaced value generated by museums was presented. Correspondently, an analysis of how such value is created should be performed. The concept of value chain was firstly introduced by Michael E. Porter in his 1985 book “Competitive Advantage” and was described as a set of activities that an organization carries out to create value for its customers, which is the fundamental purpose of any entity. It is in these value activities, considered as “discrete building blocks”, that the competitive advantage of a business resides. Porter classified them into two broad types:

• Primary activities: are the ones involved in the physical creation of the product/service and its sale and transfer to the buyer, as well as, the after-sale assistance.

• Support activities: are the ones that support the primary activities by playing a specific role.

The following graphical representation shows how the traditional organizational processes are divided into the two aforementioned categories of value-generating activities.

29 Figure 4: Porter’s Value Chain (Porter, 1985)

However, some difficulties are encountered when trying to fit cultural institutions’ processes within this classical value chain. In 2006, Porter himself redefined the concept of value chain for museums in a set of slides entitled “Strategy for Museums”, which was presented to the American Association of Museums.

Figure 5: The Museum Value Chain (Porter, 2006)

In this framework, ten strategically important activities carried out by museums are identified, each one of them being a source of value and of cost. As observed in Figure 5, according to Porter, museums’ primary activities concern the acquisition of cultural heritage for its preservation and further exhibition and communication to the community. Supporting these

30 activities are the firm infrastructure, the human resources, the financial aspect, the content and the educational programs.

The museum’s surplus will depend on whether these activities are carried out efficiently and effectively; this last issue depending on the value museums are able to deliver to their visitors. Differing from the original model, when analyzing cultural institutions, Porter does not define the value generated in financial terms but as social benefits, which include customer value, community outreach, and public service (Kotler N., Kotler P., & Kotler W., 2008). This approach is consistent with the five types of value identified by the Netherlands Museums Association, and that were described in the previous section. A correct business model identifies what customers value and levers on its own activities based on it. In this way, museums will achieve excellence in the eyes of their consumers and perform effectively in the marketplace (Kotler N., Kotler P., & Kotler W., 2008), obtaining a competitive advantage. Besides Porter, the authors Normann, & Ramirez (1993) focus on the importance of the customers as well but changing perspectives: instead of considering sequential value activities, they propose a value-creating system in which there are different stakeholders – suppliers, partners, customers - positioned in a constellation, co-producing value. They argue that successful companies do not just add value through their operations, but they reinvent it according to stakeholders’ needs. Consequently, the strategic task is to reconfigure the relationship between the firm and the constellation of actors who create value by themselves from the company’s various offerings. In this optic, strategy is conceived as a systematic social innovation: the continuous design and redesign of business systems. A good example is that of the Swedish brand IKEA, which became the world’s largest retailer of home furnishings by proposing a new business formula. Instead of positioning to add value through a series of sequential activities, it has redefined value as one in which customers are also suppliers (of time, labor, information and transportation) and suppliers are also customers (of IKEA’s business and technical services). By stressing the value of interaction and active participation, this reasoning becomes coherent with the changing role of museums as experience providers; museums’ focus has shifted from collections to audiences, so visitors assume a central role in creating their own value as the main agents of change (Ferraro, 2011).

31 In another version of the value chain model, Bakhshi, & Throsby (2009) of Nesta 3 incorporate

explicitly the presence of different actors as well. In Figure 6, it can be observed that beyond the cultural institution there are also the customers, the funding bodies and the artists.

Furthermore, the interactions between the several actors are presented, differentiating between production, distribution and consumption of artistic content on the one hand, and the flow of content, services and money on the other. It is worth mentioning how this presented division follows almost perfectly the operations described in ICOM’s definition of a museum as an organization that “[…] acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits […]”.

Figure 6: Nesta’s value chain for cultural institutions (Bakhshi, & Throsby, 2009)

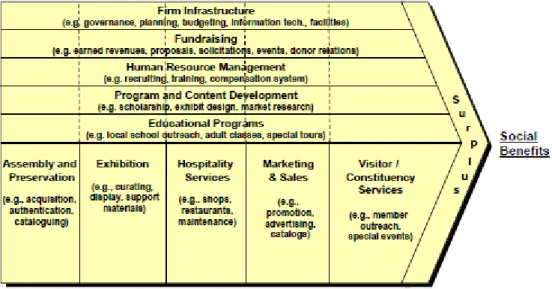

The last presented model regarding museums’ value chain and operations is the one proposed by Ferraro in the research paper entitled “Restyling museum role and activities: European best practices towards a new strategic fit” (2011). In the developed framework, Ferraro integrates the traditional and well-established museal activities - conversation, display and service – with new directions in museum management. The latter refers to the alignment of museums’ strategy to co-production, governance and new learning and entertainment opportunities, as well as determining a shift towards being a place for multi-sensorial experiences. To successfully achieve such integration, Ferraro’s museal value system combines elements extracted from different sources and authors including: Porter’s value chain, ICOM’s standards, ICOM’s Code of Ethics and the Italian legislative decree n.112/98 (“Conferimento di funzioni e compiti amministrativi dello Stato alle regioni ed agli enti locali”), among others.

3 Nesta is a global innovation foundation, based in the UK, which supports new ideas that tackle the challenges

society is currently facing. It operates in different fields, among which creative economy & culture, education, public administration and health. Furthermore, it collaborates with the UN and the European Commission.

32 As a result, four clusters of museum activities are identified:

• Research and Conservation: groups the activities related to “making and maintaining collections”, i.e. the acquisition, documentation and conservation of heritage. As so, this area concerns the most traditional museal functions.

• Valorization and Communication: this group represents the integrated system of museal offer, comprehending all the activities related to display management and the relationship with the public.

• Support Activities: includes all the strictly instrumental activities like Human Resources Management, Planning and Control, Fund Management and IT systems. • Networking and Governance: this last cluster encompasses all the activities relevant

for museum’s offer integration, governance and functional integration, since networking has proved to be pivotal for museums’ survival. Indeed, the integration between the museum and the territory in which they are present is a characterizing issue in the European context, where the dialogue with the community is the center of museum management.

In Figure 7, the detailed activities under each category can be observed. This framework integrates successfully several models and captures both traditional museum activities with new trends like customer participation and the importance of networking. As a consequence, Ferraro’s framework will be the one utilized as reference model for the present thesis.