UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PISA

F

ACOLTÀ DI

M

EDICINA E

C

HIRURGIA

Dipartimento di Medicina Clinica e Sperimentale

S

CUOLA DI

S

PECIALIZZAZIONE IN

P

SICHIATRIA

Direttore: Prof.ssa Liliana Dell’Osso

T

ESI DI

S

PECIALIZZAZIONE

The Affective Temperaments in Mania:

the influence on clinical features and

functional outcome

R

ELATORE

:

C

ANDIDATA

:

Dott. Giulio Perugi Dott.ssa Daniela Cesari

INDEX

PAGE1. SUMMARY

4

2. INTRODUCTION

5

2.1.

HISTORICAL

BACKGROUND

7

2.2.

PREDICTORS

OF

OUTCOME

OF

BIPOLAR

DISORDER

11

2.2.1.AGEATONSET

11

2.2.2.SYMPTOMSSEVERITY

12

2.2.3.GENDERANDPRE-ILLNESSCONDITIONS

14

2.2.4.PSYCHIATRICCOMORDITY

14

2.2.4.1 SUBSTANCE ABUSE

14

2.2.4.2 ATTENTION DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVIY DISORDERAND ANXIETY DISORDERS

15

2.2.5.AFFECTIVETEMPERAMENTS

15

2.2.6.LIFEEVENTS

17

2.2.7.NEUROCOGNITION

18

2.2.8.SUICIDALRISK

19

2.2.9.TREATMENT

20

2.3.

FACTORS

PREDICTING

THE

COURSE

OF

MANIA

22

2.3.1.CLINICALANDSOCIO-DEMOGRAPHICFEATURES22

2.3.2.MIXEDMANIA

27

2.3.3.TREATMENT

32

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

38

4.1.

STUDY

DESIGN

38

4.2.

SAMPLE

40

4.2.1.

INCLUSION CRITERIA40

4.2.2.

EXCLUSION CRITERIA40

4.2.3.

TREATMENTS40

4.3.

DEMOGRAPHIC

AND

OTHER

PATIENTS

MEASUREMENTS

42

4.3.1.

DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT42

4.3.2.

SYMPTOMATOLOGY ASSESSMENT43

4.3.3.

FUNCTIONING ASSESSMENT43

4.3.4.

TEMPERAMENT ASSESSMENT44

4.3.5.

CHILDHOOD TRAUMA ASSESSMENT44

4.4.

STATISTICAL

ANALYSES

46

5. RESULTS

48

6. DISCUSSION

51

7. CONCLUSIONS

58

8. TABLES

60

9. REFERENCES

71

1.

S

UMMARY

Background: Affective temperaments have been shown to impact on the clinical manifestation and on the course of Bipolar Disorder (BD); in the present study we investigated their influence on clinical features and functional outcome of mania.

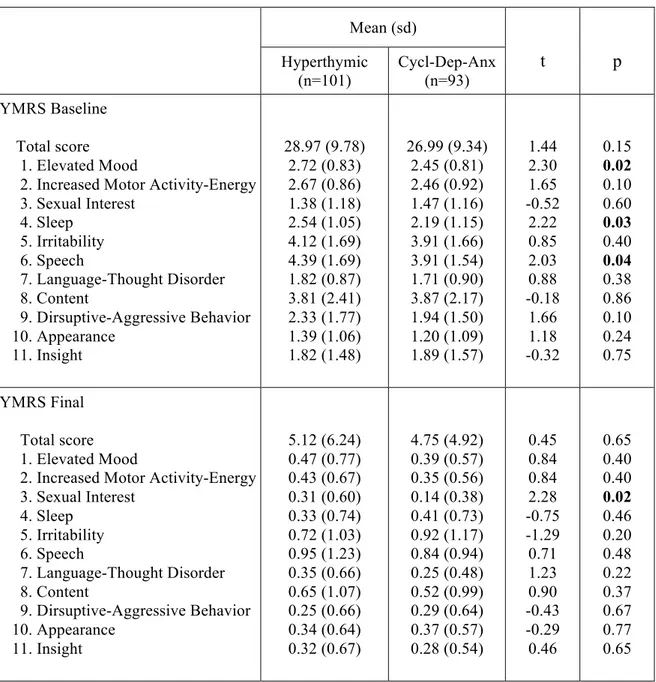

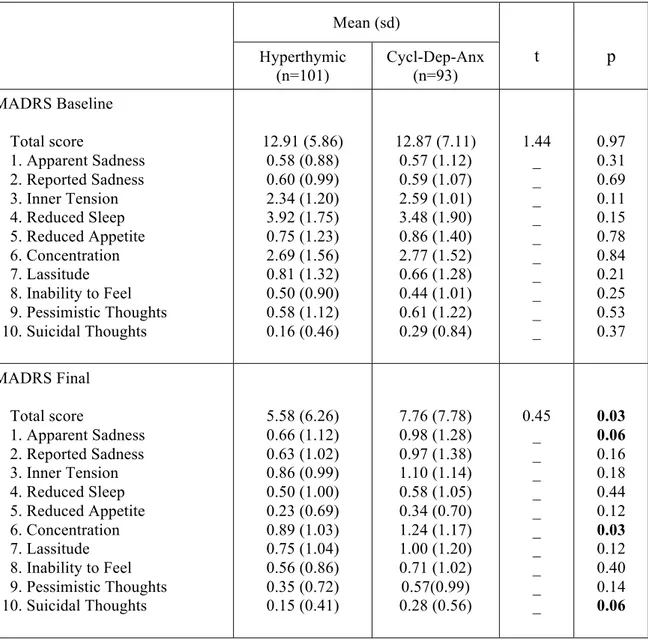

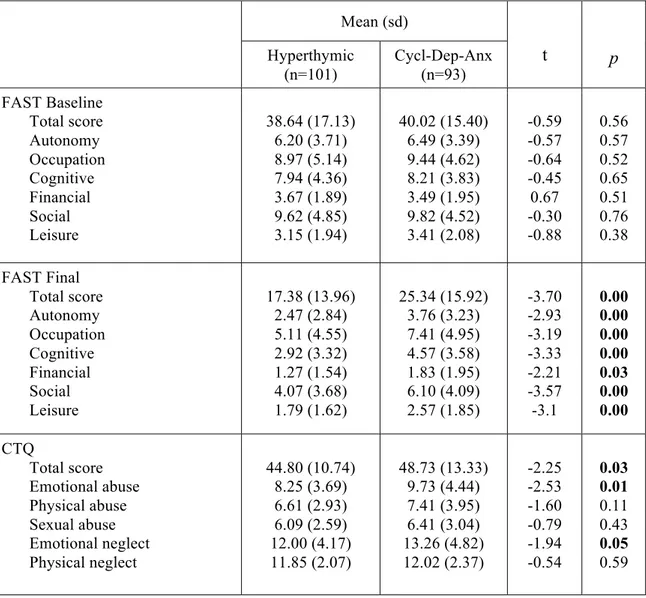

Method: In a naturalistic, multicenter, national Study, a sample of 194 BD-I patients with DSM-IV-TR manic episode underwent a comprehensive evaluation including the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), the Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST), the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego brief-version (briefTEMPS-M) scale, the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Bipolar Illness (CGI-BP). Factorial, correlation and comparative analyses were conducted on different temperamental subtypes based on the briefTEMPS-M profile.

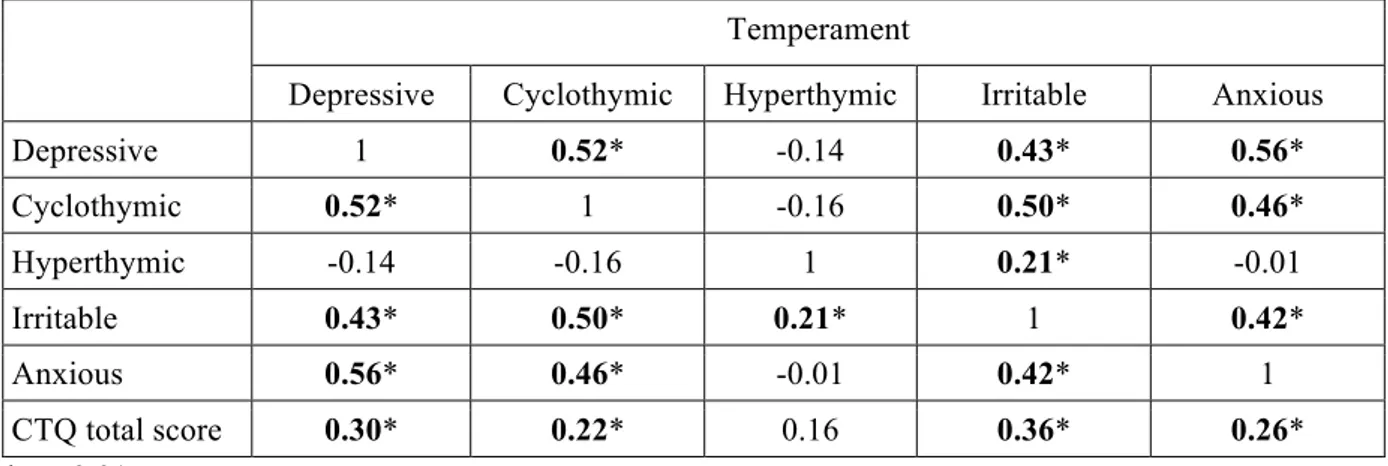

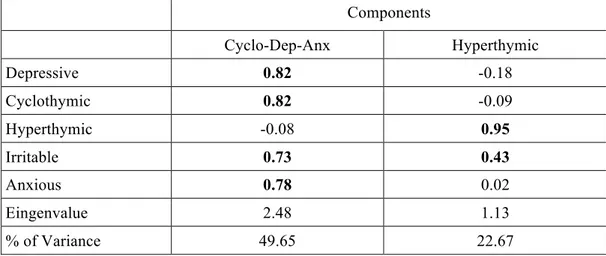

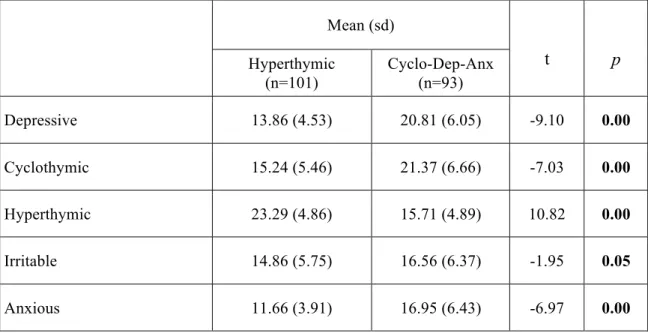

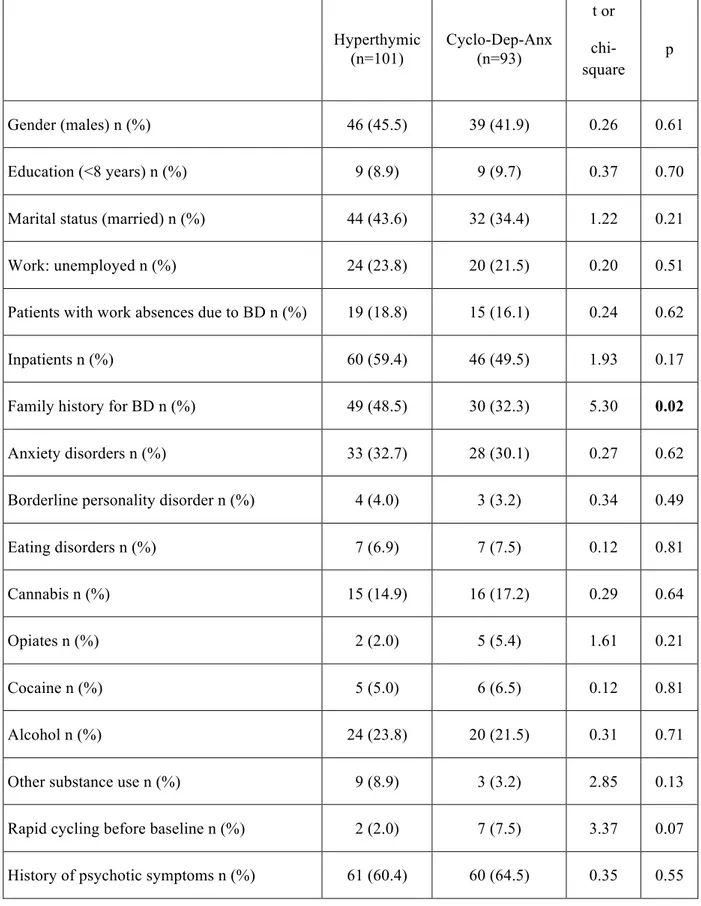

Results: Depressive, cyclothymic, irritable and anxious temperaments resulted significantly correlated with each other. On the contrary, hyperthymic temperament scores were not correlated with the other temperamental dimensions, with the exception of irritable temperament. The factorial analysis of the briefTEMPS-M sub-scales total scores allowed the extraction of 2 factors: the Cyclothymic-Depressive-Anxious (Cyclo-Dep-Anx) and the Hyperthymic. No differences between the two temperamental subtypes were observed in lifetime comorbidity and in demographic-clinical characteristics, with the exception of a higher family history for BD in Hyperthymic group. At final evaluation the Hyperthymic patients showed a greater functional outcome, as measured by FAST sub-scales, compared to Cyclo-Dep-Anx patients. On the other side, this latter group was associated with greater depressive symptoms and history of childhood emotional neglect an abuse compared to Hyperthymic group.

Conclusions: Our results support the view that affective temperaments influence the course of mania. In particular, in manic patients the presence of Hyperthymic temperament is associated with lower rates of depressive symptoms and childhood trauma and with a better functional outcome.

2.

I

NTRODUCTION

Despite modern advances in pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments, the

natural course of bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by a highly recurrent course with

frequent chronicity and consequent impairment of psychosocial functioning and

health-related quality of life [1-3].

The primary goal of acute treatment in mania is to improve symptoms, whereas the maintenance therapy is mainly aimed to achieve remission and to prevent or delay the time to relapses and recurrences [4-6]. Unfortunately, manic patients may respond differentially to pharmachological treatment due to variability in symptomatological presentations and differences in other clinical variables that can result in failure to obtain or sustain remission [7].

Remission is a multidimensional concept in BD that includes both symptomatic remission and functional recovery. Symptomatic remission is the resolution of the symptoms of the disorder, which should disappear or at least decrease to a minimal level. Functional recovery is the ability to return to an adequate level of functioning and includes an assessment of occupational status and living situation [8-11]. As a consequence, remission rates are dependent on the criteria used to define remission, the scales used to measure

outcome, and the patient population studied [9].

Although BD is considered to have a more favorable prognosis than schizophrenia, incomplete sintomatological remission and persisting alterations of psychosocial functioning are not uncommon. Previous studies reported that the majority of patients achieve symptomatic remission but less than half achieve functional recovery within 24 months of a

manic/mixed episode [7, 10-12]. Observational long-term studies on patients with BD

particular, BD I patients were unable to carry out work role functions during 30% of assessed months, which was significantly longer in comparison to patients with unipolar major depression or BD II (21% and 20%, respectively)[13].

For this reason, there is a growing interest in the factors associated with outcome and remission in BD patients [12, 14, 15]. Several studies have explored the role of socio-demographic and clinical features in predicting remission [12, 14-16]. In particular some authors have investigated the influence of affective temperaments on the course of BD [17-19].

In our knowledge this is the first study investigating the influence of affective temperaments on clinical features and functional outcome of BD patients experiencing a manic episode.

2.1.

H

ISTORICAL BACKGROUND

There was a long tradition, upheld by John Monro (1758), that “insanity” was

incurable [20] In their authoritative manual, Bucknill and Tuke spoke about the constant

tendency of mania, and other forms of mental disorder, to pass into dementia [21]. This observation summarized the nineteenth century concept of mania as a condition commonly leading to mental (i.e. intellectual) deterioration. This was a prejudice which, said Esquirol, “has proved exceedingly fatal to manics” because it led physicians to neglect both the treatment of such patients and the study of mental disorder. With the worthy aim of refuting this prejudice, Esquirol (and Pinel before him) was concerned to show that insanity was not necessarily a hopeless condition. “Experience has proved”, he wrote, “that mania is not incurable”. However neither he nor Pinel mentioned the proportion of their manic patients who recovered [22, 23].

Later in the century, during the asylums era, it became the concern of medical superintendents, which were attentive to the results reported by other asylums, to claim as high a recovery rate as possible. Perhaps it was partly for these reasons that there seems to have been no very serious effort to define what was meant by cure or recovery. Thus recovery might mean only that the patient did not die or did not immediately pass into a state of dementia. Some authors gradually began to note that those patients who were considered to have “recovered” nevertheless often failed to return to their previous state. Thus Griesinger, in 1867, said “it is not at all unusual, although it has hitherto been very little attended to, to observe a mental state characterized by moderate (mental) weakness occasionally ensue after apparent recovery from other forms (of insanity), and to remain persistent” [24].

any form of mania is preceded by a state of dullness. . . recovery may take place with a certain mental enfeeblement (the Heilung mit Defekt of Neumann)” [25]. Furthrermore Maudsley (1895) reported that recovery from mania occurs in about half the cases, but the recovery “it is not variably quite so perfect as it looks”: there is a moral blunting and “some

degree of impairment of intellectual memory may be detected sometimes after acute mania”

[26].

Nevertheless, attempts were being made to isolate a group of disorders that recovered in a strict sense, in the sense that they were never associated with decline into dementia. Here the contributions of Mendel and Kahlbaum were important [27, 28]. The first author published Die Manie (1881), a book in which he put forward a new name and a new concept: the “hypomania”. He proposed this name for “that form of mania which typically shows itself only in the mild stages, abortively so to speak”. Mendel described his hypomania as an illness “similar to the state of exultation in typical mania (but) with a certain lesser grade of development and which never comes to incoherence speech”. He wrote that all his cases of hypomania were cured, and to that extent Mendel’s hypomania is considered to be one of the earliest descriptions of a purely affective psychosis that did not lead to mental dementia [28]. Afterwards Krapelin used the term hypomania as the

equivalent of the mildest form of his mania [29].

Kahlbaum in his paper On Circular Insanity (1882) described a distinct type of circular disorder that he called cyclothimia, characterized by attacks of excitement and depression in which, unlike typical and recurrent attacks of mania and melancholia, did not end in dementia [27]. Furthermore Kahlbaum wrote that there were pure states of depression and pure states of exaltation that also not lead to dementia and for which he proposed the names dysthymia and hyperthymia. These ideas were re-moulded by Kraepelin as aspects of his manic-depressive insanity. In particular the term cyclothymia was used in the sense in which

is still used [29].

Clouston (1892), discussing the prognosis of mania, wrote that there was a complete recovery in about half the cases, death in 5 per cent, partial recovery (chronic mania) in 15 per cent; and in the remaining 30 percent, dementia (the chronic patients in asylums were of

this class) [30]. Melancholia had a similar outcome, and it is evident that the concepts of

mania and melancholia in the nineteenth century included cases later called schizophrenia

and which Kraepelin called dementia praecox [31].

Krafft-Ebing distinguished in his textbook (1898) between types of insanities that were curable and types that were not for the first time in the history of psychiatry. The author held mania and melancholia to be acquired disorders and to be curable because they were acquired and he classified them as Psychoneuroses. Other types of insanity, which tended to dementia, did so because they were due to hereditary degeneration [32]. Kraepelin took over the concept of mania and melancholia as curable, but unlike Krafft-Ebing he recognized the hereditary factor. In particular Kraepelin wrote that “attacks of manic depressive insanity… never lead to profound dementia, not even when they continue throughout life almost without interruption. Usually all morbid manifestations completely disappear; but where that is exceptionally not the case, only a rather slight, peculiar psychic weakness develops, which is just as common to the types here taken together (periodic and circular insanity, simple mania, melancholia and amentia) as it different from dementias in diseases of other kinds”. This type of psychic weakness occurred in 37 per cent of nearly a thousand cases that Kraepelin had studied. He described the nature of this weakness as simple personal peculiarities; such as occur in the families of manic-depressive patients. Furthermore Kraepelin suggested that this weakness might be due to a severe hereditary taint, or to long residence in an institution, or to approaching age, or even to a postulated

From the above considerations it is clear that the distinction between mental disorders that tended to progress to permanent mental enfeeblement (what the nineteenth century called dementia) and those which did not, first clearly emerged in the early 1880’s with the publications of Mendel and Kahlbaum [27, 28].

In the article “the two manias”, Hare (1981) explained why that distinction has emerged only at that time. The author suggested that under the influence of Griesinger, psychiatry had become an academic subject in Germany by the mid-nineteenth century. But it was dominated by Griesinger’s concept of the Einheitspsychose, and so the university research and teaching was likely to have been based on acute case, studied over a short period of time. Instead Kahlbaum worked for more than 30 years at a single institution and was therefore well placed to detect syndromes on the basis of long-term outcome. An additional explanation was that mental deterioration which was the common sequel of insanity during the nineteenth century, was due, at least in part, to the relative poor state of general health, and to the consequent low resistance to disorders affecting mental function. This idea could permit a reconciliation of two opposing views held during that century: the view that all insanities were essentially similar and tended to dementia, and the later view that there was a type of insanity in which the intellectual function was not significantly affected. Under the conditions of poor hygiene and poor general health that existed during much of the nineteenth century, most insanyties did tend to dementia. But as the general health of the population gradually improved, this tendency became less; and the effect of this was first apparent in the group of affective disorders, so allowing their identification in the century as a distinct, non-dementing group [24, 31].

2.2.

P

REDICTORS OF OUTCOME OF

B

IPOLAR

D

ISORDER

2.2.1. Age at onset

Patients tipically experience their first manic episode in their early twenties, although it can be seen at any stage of life, from childhood to old age. Early onset BD usually has a poorer outcome with long delays to first treatment. Such patients experience more episodes, rapid cycling and demonstrate severe mania, depression, prominent psychotic and anxiety features, substance abuse and fewer days well [33-38]. Some authors reported that, although most bipolar adolescents experience syndromic recovery following their first hospitalization, rates of symptomatic and functional recovery are lower compared to adults [39-41]. Available results consistently indicated that between 70% and 100% of children and adolescents with BD recover from their index episode, however, up to 80% experience

multiple recurrences [42]. In addition, several studies indicated that approximately 30% of

preadolescents with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) experience a manic episode and manifest BD within 5 years [43].

The poor outcomes in early onset BD may reflect: a) particularly virulent longterm illness following juvenile onset, b) effects of prolonged delay or refusal of treatment in childhood and adolescence, c) impressions arising from juvenile illnesses that may not be expressed in more clearly episodic, adult form, or d) possible destabilizing effects of antidepressants and stimulants commonly used to treat children and adolescents with behav- ioral symptoms [37, 42, 44]. Another possibility is that BD considerably affects the normal

psychosocial development of a child and increases the risk of academic, social, and interpersonal problems (e.g. family, peers, and work), as well as risk of poor health care

utilization [45]. However, not all reports support the hypothesis that early onset BD follows

Early onset BD may also represent a phenotype of special interest for genetic research [48-50]. Genetic interest arises in part from relatively high rates of familial mood disorders in BD, generally, and particularly in association with young onset [37, 48-51].

In contrast, mania in the elderly appears to be a heterogeneous disorder, in which first-episode mania (very late onset) patients have a negative family history for BD and are

twice as likely to have an associated comorbid neurological or medical disorder [52]. In

particular late onset mania is frequently associated with ataxia, cognitive disorders (i.e. reduced attention and concetration), disorientation and confusion. The medical conditions that can lead to mania are metabolic disorders (i.e. uremia, hyperthyroidism and carcinoid syndrome), infectious diseases (i.e. encephalitis, meningococcal meningitis, HIV), tumors (i.e. brain tumors such as diencephalic glioma, meningioma parasellar, suprasellar tumor diencephalic), vascular brain injury, traumatic brain injury, epilepsy (i.e. right temporal focus) and other neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis, Huntington's disease and Kleine-Levine syndrome. In addition, substances such as psychostimulants (amphetamines, methylphenidate, cocaine), levodopa, yohimbine, corticosteroids, sympathomimetics and antidepressants can also induce a manic episode [53].

Finally first-episode mania in the elderly is often charachterized by mixed features and reported a higher risk of relapse and mortality compared to patients with a multiple episodes

history of mania [52, 53].

2.2.2. Symptoms severity

The STEP-BD project (Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for BD), a multistate observational study [54] conducted in U.S.A., reported an initial recovery by 58% of patients, with half of them experiencing recurrences after 2 years of follow up and more than twice developing depressive versus manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes. Factors that

significantly influence the depressive recurrence included residual depressive or manic symptoms at recovery and proportion of days the subjects were depressed or anxious in the preceding year. Therefore reducing the risk of recurrences, which are frequent and associated with affective symptoms at initial recovery, can be achieved by identifying residual symptoms in BD.

Recent data suggested that, apart from the presence of chronic subsyndromal symptoms, the occurrence of depressive symptoms also predicts the shorter time to a new episode of BD. It was also observed that the presence of subsyndromal depressive symptoms during the first two months after recovery increases the likelihood of depressive relapse [55]. It is also noteworthy that patients with psychotic symptoms and those with a greater number of previous depressive episodes are more likely to exhibit subsyndromal depressive symptoms [56, 57].

Another study reported that changes in severity of mania or hypomania are not significantly associated with differences in functional impairment while modest changes in severity of depression are associated with statistically and clinically significant changes in disability and functioning in patients with BD [58]. Conversely Nolen and colleagues (2004), in the 12-month Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network outcome study, reported that the mean rating for severity of mania is associated with comorbid substance abuse, history

of more than ten prior manic episodes, and poor occupational functioning at study entry [59].

Furthermore in naturalistic settings, patients with mania and rapid cycling differed from non-rapid cycling in pharmacological treatments, socio-demographic features and clinical outcome measures with significantly worse occupational outcome and psychiatric comorbidities [58, 60].

Finally, mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms during the index manic episode are associated with a shorter time to remission at 4 years [58, 60].

2.2.3. Gender and pre-illness conditions

Gender can be a predictor of outcome, with significant differences between males and famales. Women have more depressive episodes, with higher rates of comorbid eating disorders, weight change, and insomnia. Men have early onset associated with manic episodes, higher probability of childhood antisocial behavior, higher rates of comorbid

alcohol and cannabis abuse/dependence, and pathological gambling [61].

Furthermore a poor psychosocial functioning before the onset of the illness predicts a worse outcome of BD [62, 63].

2.2.4. Psychiatric comorbidity

Patients with BD often experience comorbidities, including substance-use disorders, with deleterious effect on the prognosis of the disease. In fact psychiatric comorbidity is often associated with earlier onset of BD, worse course, poorer pharmacological treatment adherence and more severe outcome (more risk of suicidal behavior and other complications) [64, 65].

2.2.4.1. Substance abuse

BD patients with comorbid substance-use disorders of any kind may present clinical features that could compromise compliance and response to treatment. Moreover, the presence of comorbid substance-use disorders is associated with a significantly more impairment in social functioning, less likelihood of receiving a diagnosis of BD I, and severe manic symptoms [66].

In particular comorbid alcoholism in patients with BD leads to poorer psychosocial functioning and slower recovery [16, 67]. Patients with alcohol-induced disorders prior to the onset of BD are usually older and more likely to recover faster compared to those whose alcohol problems commence after BD is diagnosed and tend to experience more time with symptoms and mood episodes.

The results of the onset sequence of BD and cannabis-use disorders are less pronounced than the effects observed in co-occurring alcohol and BDs [68]. However cannabis-use is associated with more time in mood episodes and with rapid cycling. It is also noteworthy that most cannabis-use disorders remit immediately after hospitalization, followed by high rates of recurrence.

2.2.4.2. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Anxiety disorders

Comorbid attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and anxiety disorders,

including those present during relative euthymia, predict a worse course of BD [69, 70]. In

particular, comorbid panic disorder is associated with a higher likelihood of rapid cycling [71].

Interestingly, Krishnan and colleagues (2005) reported that comorbid anxiety disorders impacts health-related quality of life in patients with BD I, but not in patients with BD II

[72].

2.2.5. Affective temperaments

Affective temperaments (e.g. cyclothymia and hyperthymia) are supposed to have an impact on the clinical manifestations and on the course of BD [17, 18, 72]. In particular temperaments might play a predisposing or pathoplastic role in in several co-morbid

A study conducted in a sample of Bipolar I patients, focused on the relationship between temperaments and mixed states [74, 75], supported the hypothesis that mixed episodes are more frequent in subjects with inverse temperaments [76]. In other terms, patients with depressive temperament tend to present mixed mania and patients with hyprthymic temperament mixed depression.

In a recent paper Perugi and colleagues (2012) explored, in a national sample of BD I patients prospectively evaluated during the euthymic phase, the influence of affective temperaments and psychopathological traits (separation anxiety and interpersonal sensitivity) on the clinical features and the course of BD. In that group of BD I patients, correlation analyses indicated that depressive, cyclothymic, irritable and anxious temperaments were strongly and inversely related with hyperthymic traits [19]. These data were consistent with previous observations in German [77] and Hungarian [78] clinical samples, as well as in general Lebanese population [79]. From the psychometric point of view, the affective temperamental dispositions were 2: the depressive–cyclothymic– anxious–irritable (cyclothymic) and the hyperthymic. The first seems to be characterized by emotional instability and the second by emotional intensity.

The comparison between the two groups of BD patients with different dominant temperaments confirmed an overrepresentation of the female gender among cyclothymic-sensitives. This data was consistent with previous results in general [80] and clinical [74, 81, 82] populations. Interestingly, the cyclothymic-sensitive patients reported a prevalently depressive course (more depressive and hypomanic episodes), while hyperthymic patients showed more severe manic episodes requiring hospitalization.

As expected, suicide attempts were more numerous in cyclothymic rather than in hyperthymic patients, probably reflecting, at least in part, the high incidence of depressive

episodes. No difference between the two groups was observed in the number of mixed episodes, defined by DSM-IV criteria [83].

The two temperamental subgroups reported also a different profile in terms of axis I lifetime co-morbidity. Cyclothymic-sensitive patients presented more frequently than hyperthymic co-morbid anxiety disorders (Panic/Agoraphobia and Social Anxiety Disorders) and, although not statistically significant, higher rates of Eating Disorders.

Furthermore dominant cyclothymic patients reported more than double rate of first-degree family history for mood and anxiety in comparison to hyperthymic patients. Concerning drug and alcohol abuse, the two groups showed similar rates of lifetime co-morbidity, suggesting a relative lack of association of this variable from the temperamental profile.

Exploring axis II co-morbidity, although the two groups were similar concerning Borderline personality disorder prevalence. On the contrary, Antisocial personality disorder was more represented among hyperthymic than cyclothymic patients, in particular for features such as “failure to conform to social norms concerning lawful behaviors as indicated by repeatedly performing acts that are grounds for arrest” and “consistent irresponsibility, as indicated by repeated failure to sustain consistent work behavior or honor financial obligations”. The author suggested that chronic hypomanic attitudes partially overlap with other externalizing developmental disorders such as attention-deficit-hyperactivity and conduct disorders frequently associated with antisocial personality [84].

2.2.6. Life Events

Some authors suggested an inverse relationship between life events and biological predisposition. In particular, in patients with a strong familial history for BD, minor events

can lead to the development of severe manic/depressive episodes. Nevertheless BD patients often reported severe stressful life events that are associated with slower recovery and higher relapse rates [43, 85]. Moreover an array of stressors may be relevant not only to the onset and progression of affective episodes, but also to the highly prevalent substance-abuse comorbidities as well [86].

Surprisingly a significant interaction between stress and number of episodes in the prediction of BD recurrence has not been reported; however, the interaction of early stressful and serious life events significantly predicts recurrence in a manner consistent with the

sensitization hypothesis [87].

Furthermore a history of childhood abuse acts as a disease course modifier in patients with BD [88]. In fact a childhood abuse may be a risk factor for vulnerability to early-onset illness [86]. On the contrary the number of early losses are no associated with BD

psychopatology and course [89].

Finally studies have examined that BD patients who are more distressed by their relatives’ criticisms reported a more severe symptomatology and a worst quality of life [90].

2.2.7. Neurocognition

Some data report that neurocognition declines is more stable in BD in comparison to schizophrenia. A recent study found that during a 5-year period, BD patients showed stability over time in attentional measures, while schizophrenic subjects exhibited significant deterioration in executive functioning [91].

In symptomatic and remitted BD patients an impaired insight and other neurocognitive dysfunctions are correlated [92]. Cognitive impairment seems to be related to a poorer

clinical course and a worse functional outcome. Verbal memory appears to best predict psychosocial functioning in BD patients, with low-functioning patients being more impaired

than highly functioning patients in executive functions and in verbal recall [9, 93].

Recent findings indicate that patients with BD lose hippocampal, fusiform, and cerebellar gray matter at an accelerated rate compared with healthy control subjects. Some authors suggest that this tissue loss can be associated with deterioration in cognitive function

and illness course [94].

2.2.8. Suicidal Risk

Patients with mood disorders have a higher risk of death by suicide (15% to 30%) and

BD II patients are at greater risk than BD I patients [61]. It has been reported that 25% to

50% of patients with BD attempt suicide at least once in their lifetime [95].

The polarity of patients’ first mood episode indicates a depression-prone subtype with

a greater risk of suicide attempt [96]. Mixed states or the presence of mixed features are also

reported to increase the probability of suicide [97].

Furthermore, comorbid anxiety disorders (i.e. panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder), obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder may also play a role in BD course by elevating the risk for suicidal ideation and attempts [98]. The risk of sucidal behavior is also higher in presence of previous suicide attempts, in patients with alcohol abuse or with a chronic medical disorder [99].

Finally, there are socio-demographic conditions that increase the probability of suicidal behaviors such as separation or divorce, be widowed, social isolation and male gender. Suicide is more common in males, while females report a higher number of suicide

2.2.9. Treatment

The treatment of BD should influence the course of disease in a positive way. Early intervention and effective treatment are the ultimate goals, but early identification has several difficulties which cause approximately 10 years of delay from a patient’s first

episode of illness to diagnosis [102, 103], invalidating the effectiveness of the early

treatment intervention [104]. This suggests that the initial lithium therapy within the first 10 years of onset of BD might be more promising than prophylaxis in later life. Similarly, maintenance therapy also results to be more effective early in the course of BD. A recent study reports that early-stage patients had significantly lower rates of relapse and recurrence of manic/mixed episodes with such treatments [104]. Furthermore, a history of multiple episodes may be associated with poor response to lithium treatment and that patients with

higher numbers of manic episodes show worse outcomes [57, 105, 106]. These data indicate

that preventing recurrent episodes early during the disorder could improve a patient’s long-term prognosis.

In addition, specific guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of early-phase BDs

are not available [107]. In fact the initial prodrome of BD has received very little attention to

date and there are no prodrome symptoms that clearly distinguish between patients who

develop BD and those who develop other psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia [108].

Several studies suggest that the polarity of the index episode tends to predict the polarity of the subsequent affective episode: a manic index episode tends to predict a manic

relapse, whereas a depressive or mixed index episode predicts a depressive relapse [10, 105].

Patients with BD categorized by subtype episodes have significant differences in the time of remission [109]. A median follow-up of 18 months reported that the estimated probability of remaining ill for at least one year was 7% for the pure manic patients, compared with 32% for patients that were mixed or cycling, and 22% for the unipolar depression patients. It

appears that a patient with a first manic (rather than depressive) episode tends to experience

2.3.

F

ACTORS PREDICTING THE OUTCOME OF

M

ANIA

2.3.1 Clinical and Socio-Demographic Features

In patients with BD, manic episodes produce a substantial personal and economic

burden [112], that could be alleviated with a rapid symptoms resolution [41].

Data from a prospective cohort study showed that after the first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode, most patients achieved syndromal recovery after two years, 28% of them remained symptomatic, but only 43% of patients achieved functional recovery. Moreover, 57% of those patients who achieved syndromic remission switched phases or had new illness episodes during the first two years after recovery [11].

These results suggested that patients with mania could present different treatment responses probably due to variability in clinical and socio-demographic dimensions that can influence the short and long-term course [7].

Psychopathological heterogeneity in manic syndromes may in part reflect underlying latent classes with characteristic outcome patterns. Van Rossum and colleagues (2008), in a 12 weeks study, examined the differential treatment course and outcome for three distinct classes of patients with acute mania. Three thousand four hundred and twenty-five patients with acute mania were divided into ‘Typical’, ‘Psychotic’ and ‘Dual’ (i.e. comorbid substance use) mania patients. Persistence of class differences and social outcomes were examined, using multilevel regression analyses and odds ratios. Psychotic and Dual mania predicted poorer outcome in terms of psychosis comorbidity and overall bipolar and mania severity, while Dual mania additionally predicted poorer outcome of alcohol and substance abuse. Worse social outcomes were observed for both Dual and Psychotic mania. Overall,

Dual and Psychotic mania show less favourable outcomes compared to typical mania [113]. These latter results are in line with those of other studies in which mood incongruent psychotic features and the presence of substance abuse were predictors of manic relapse and delayed symptomatic remission, respectively [16, 114].

EMBLEM (European Mania in Bipolar Evaluation of Medication) is a large-scale 2-year European prospective observational study designed to evaluate the clinical, functional and economic outcomes of pharmacological treatment of patients with an acute manic or mixed episode of BD. In a study conducted in EMBLEM sample, the type of acute episode (manic or mixed) did not influence the rates of remission or functional recovery over the 2-year follow-up [12]. This is surprising given that mixed mania is generally considered to have a worse course and prognosis compared with pure mania in both the medium and long term, as we’ll better explain in the course of the present thesis [115, 116].

Always in the same study, Haro and colleagues (2011) reported a better remission outcome in manic patients with a lower symptoms severity as measured with the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Bipolar Illness (CGI-BP) [12]. In contrast with this data, some authors suggested that the level of functional impairment may not be directly related to the symptomatic severity of the index manic episode but, rather, reflect the extent of prior illness course. In fact patients with repeated episodes and a longer course of illness become progressively less responsive to treatment [11, 117-119].

In another analysis of the EMBLEM database, Tohen and colleagues (2010) compared baseline characteristics and outcomes in patients with first or multiple episodes of acute mania. This study is unique considering its large sample size (n=3.115), which allowed comparison between first- and multiple-episode patients within the same sample population. First-episode patients reported higher baseline illness severity, degree of

symptom improvement and comorbid substance use than multiple-episode patients. Instead the latter group showed a higher functional impairment compared to first-episode group. These findings highlight important distinctions in illness characteristics, outcome, and possibly treatment response between patients at different points in the longitudinal course of bipolar disorder. Baseline illness severity, as reflected in Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score, CGI-BP mania score, incidence of hospitalization at study entry, and proportion of patients with an episode lasting ≥ 8 weeks, was significantly greater in the first-episode relative to the multiple-episode cohort. Nevertheless, self-reported ratings of functional impairment (work impairment, satisfaction with life) were significantly worse in the multiple-episode cohort [120]. Indeed, other studies showed that the degree of cognitive and functional impairment associated with BD increases with the number of previous episodes and a longer illness duration [121, 122]. Consistent with previous reports [11], the vast majority of first-episode patients in this study achieved symptomatic recovery and significantly greater baseline-to-endpoint decreases in CGI-BP overall, CGI-BP mania, and YMRS scores, relative to multiple-episode patients.

It should also be noted that a sizeable proportion of patients in both groups (46% first-episode, 49% multiple-episode) reported the persistence of subsyndromal symptoms. Previous studies have shown that the presence of subsyndromal symptoms impairs functional outcomes and increases the probability of a subsequent relapse [11, 55].

Kora and colleagues (2008) have conducted an observational, prospective, multicenter study in Turkey (2003-2005) to determine the time to remission and recurrence after the treatment of a manic or mixed episode in inpatients and outpatient with BD. They also examined predictive factors associated with a longer time to remission and a shorter time to recurrence. The presence of psychiatric comorbidities, a higher baseline YMRS score [123], and a higher number of previous depressive episodes were found to be

statistically significant predictors for a long time to achieve remission [14].

In line with Kora results, other authors underlined an association between depressive episodes or symptoms and a delayed recovery [11, 12, 120]. Tohen and colleagues (2010), in the study previously described, reported that multiple-episode patients had a higher baseline level of depressive symptom severity as documented by the CGI-BP depression and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-5) scores [120]. Also experiencing a depressive episode in the year before mania predicted a worst remission outcome [12]. In addition, several studies showed that a higher Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) [124] anxiety/depression score and higher initial depression ratings were significantly associated with a longer time to remission [11, 114, 125].

Moreover other clinical factors related with longer time to syndromal and functional recovery are a long hospitalization time and the presence of childhood psychopathology [11, 114, 124, 125].

Available data in literature reported a relationship between socioeconomic status and mania outcome [16, 114]. In fact, a lower socioeconomic status has been associated with delayed symptomatic remission, whereas a higher socioeconomic status and good pre-morbid functioning (e.g. living independently, forming relationships, etc) was associated with faster functional recovery over 12 months. Students were the most likely to recover, followed by skilled/professional, semiskilled, and then unskilled/unemployed workers. Impairment in work functioning was associated with lower rates of functional recovery as well as lower rates of remission [16]. Also in more recent studies, a lower premorbid occupational status was a predictor of manic relapse and a good work or social functioning (no work impairment and socially active) were associated with better remission outcome [12, 114]. In addition, not being in a relationship, not living independently and lower

educational levels (compared to studying to university level), contributed to lower functional recovery [12]. Finally, in regard of other demographic features, younger age at onset [114, 124] and male gender are reported to be associated with a longer time to remission [11, 114, 125].

2. Mixed Mania

It has long been recognized that more than pure manic features such euphoria, grandiosity, flight of ideas, increased drive and psychomotor excitement, characterized the clinical manifestation of acute mania. Atypical manic features such as depression, anxiety, irritable aggression, and psychosis have sometimes been described as occurring with pure

manic features and are prominent in some patients with mania [126].

A this purpose, Robertson (1890) proposed two varieties of acute mania: hilarious mania

and furious or raging mania [127]. Subsequently Kraepelin (1921) suggested several mixed

manic states with psychomotor or thought inhibition (inhibited mania, mania with poverty of thought, and manic stupor) [29].

In the last 30 years, a rebirth of interest in mixed states produced studies on mania plus subsyndromal depression and, more recently, on major depression plus subsyndromal mania. This approach considered mixed states as subtypes of manic or depressive episodes, rather than in terms of specific features or episode components.

In particular, subsyndromal depressive symptoms have been reported to co-occur during mania in 25–40 % of patients [128-130]. There is no terminological uniformity in the literature, and there is a tendency to use terms as mixed mania, depression during mania and

dysphoric mania interchangeably.

In mixed mania, manic symptoms are reported as less severe [131], more serious [76,

131-136], or comparable in severity [137] to pure mania. Symptoms characterizing manic episodes such as grandiosity, euphoria, involvement in pleasurable activities and decreased need to sleep are less represented in mixed mania. Instead, dysphoric or irritable mood, anxiety, excessive guilt, and suicidal behavior are depressive symptoms commonly associated with mixed manic episodes.

It has been reported [138] that mixed mania is similar to agitated depression with regard to the severity of depression and anxiety, with a more severe state of agitation, irritability and cognitive impairment. In the acute phase, the emotional instability with rapid succession of intense emotional states and psychomotor agitation, sometimes violent, may be considered valuable key features for the diagnostic identification of these forms.

In the most severe cases, a dysphoric or irritable mood can be associated with severe anxiety, psychomotor excitement, accelerated speech, psychotic features (delusional thinking, hallucinatory perception) and depersonalization-derealisation phenomena. For some of these patients it is possible the occurrence of catatonic features or the evolution toward delirious state [97, 138, 139].

Moreover, most severe mixed-manic forms, characterized by psychosis, severe emotional, perceptual and motor disturbances, the association of manic and depressive features may be not easily identifiable and many of these patients are diagnosed as

schizophrenia or other related psychosis [97, 140, 141]

Therefore, the peculiar clinical characteristics of mixed mania led some authors to develop criteria for a correctly diagnosis. McElroy and colleagues (1992; 2008) firstly proposed the presence of a full manic syndrome and at least three depressive symptoms as expanded criteria for mixed mania. Thus defined, the mixed mania occurs more often in females and shows a high frequency of mixed episodes and mixed onset of the disorder and high rates of comorbidity with obsessive-compulsive disorder [116, 142].

In the Study of Clinical Epidemiology of Mania (EPIMAN), conducted in four French centers [74], using less restrictive criteria for the diagnosis of mixed episodes (presence of at least two depressive symptoms), the mixed mania was found in 37 % of patients. The symptoms with predictive value for the diagnosis of mixed state were

depressed mood and suicidal ideation. The study reported a higher prevalence of depressive temperament traits in patients with a mixed manic episode than in patients with pure manic

syndrome. Furthermore many mixed-patients could be classified as cyclothymic. The mood

instability associated to the presence of cyclothymic temperament may be the cause of the extreme emotional turbulence of these patients. The depressive and cyclothymic temperaments have a high prevalence in females and this feature could explain the greater frequency of mixed states in women.

On the basis of the previous observations, mixed manic episode can be defined in several ways: from the categorical point of view, by the presence of at least two depressive symptoms; from the psychometric point of view, on the basis of a score >10 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-18 items [143]; from the dimensional point of view, by the presence of dysthymic and depressive temperamental traits [62]. In support of this dimensional model, additional data come from the Pisa-San Diego collaborative study [144, 145] and from clinical trials.

In a recent study [141] on 202 bipolar I patients, treated with ECT, with severe treatment-resistant mixed state, only 14% of the sample can be described as “dominant manic” and 24% should be considered as “dominant depressive”; 62% of the patients were considered neither predominately-manic nor predominately-depressive. Interestingly prominent “psychotic symptoms” and “anxiety” characterized respectively 20% and 15% of the patients. Finally a substantial minority of the sample reported “negative symptoms” (18%) and “disorientation-unusual motor behavior”(7%), as dominant symptomatological features. The presence of these phenomenological characteristics in severe, treatment

resistant mixed mania, confirm previous clinical observations [29, 146, 147], and it could

The DSM-IV definition of mixed states as well as the DSM-5 [148] “mixed features” specifier for mania and depression may not be effective in capturing these features of severe mixed states [149, 150]. However, the recent DSM-5 definition of mixed features reflects a more liberal approach to mixed states. In fact the new classification will capture subthreshold non-overlapping symptoms of the opposite pole using a “with mixed features” specifier to be applied to manic, hypomanic, and major depressive episodes, experienced in BD I, BD II, BD not otherwise specified, and major depressive disorder [139].

The peculiar clinical implications of mixed states explain the importance of a correct

diagnosis of these forms. In fact, manic and depressive episodes with or without

subsyndromal symptoms of the opposite pole seem to differ in clinical and course characteristics as well as in treatment response [132, 151]. Even the presence of only two depressive symptoms, not a full mixed state, can alter treatment response during mania

[152]. Furthermore, it has been reported that patients take longer to recover from a mixed

episode than from a pure manic episode. In particular mixed mania has been associated with greater amounts of depression during follow-up, more chronicity and rapid cycling, as well as with higher rates of recurrence, psychiatric hospitalisations, comorbid substance abuse and suicidal behaviour [128].

Patients with mixed-manic episodes have a higher suicidal risk than patients with a history of only non-mixed-manic episodes [153]. A higher rate of suicidal ideation, comparable to that of depressive episodes, has been observed in mixed mania compared to non-mixed mania [74, 126, 134, 154-157]. It has been reported a higher suicidal ideation also when at least three depressive symptoms are present [155].

Concomitant anxiety and substance use disorders are more common in patients with mixed-manic [154] or mixed-depressive episodes [158] in comparison to patients with pure mania. These data are confirmed by two important longitudinal studies: the National

Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (N=43,093) [159] and the Zurich Study [160]. Comorbid anxiety disorders are associated with a poorer course of BD and with an increased use of psychiatric services [161].

Alcohol and substance abuse seems to be more prevalent in mixed-manic episode than in pure mania [162-164] and these abuses are reported to be associated with a poorer outcome and a non-response to lithium therapy [162]. However, the differences in alcohol abuse are not always confirmed [74]. Moreover, a history of substance abuse disorders predicts greater mood instability in depressive episodes [165], and possibly increases the risk for the development of mixed features and suicidal behaviour.

3. Treatment

Skillful treatment of mania remains a clinical challenge, although treatments options

have significantly increased over recent years. Antimanic treatment should be commenced at

least until full remission, syndromal and functional, as been achieved. In fact the persistence

of subsyndromal symptoms in mania is associated with a significant risk of relapse [55].

Furthermore is recommended that, when selecting a treatment regimen for mania, one consideration should be its overall efficacy and tolerability in long-term, thereby minimizing switches of medication that may be associated with an increased relapse risk

[166]. However, the absence of an early improvement after 1 week of treatment could tell

the clinician that an individual patient has only a small chance of still reaching response or remission with unchanged treatment.In this regard, the data obtained in the study of Szegedi and colleagues (2013) have important treatment implications. The authors investigated the impact of an early symptom improvement on mania outcome. Szegedi and colleagues performed a pooled post hoc analysis on datasets of two 3-week randomized controlled trials conducted in manic or mixed patients treated with asenapine, olanzapine, or placebo. In acute manic episodes, an early improvement within 1 week of treatment was associated with significantly increased odds ratios of endpoint response or remission. The predictive value of early improvement tended to be strongest and occurred earliest with asenapine treatment, followed by olanzapine and placebo [167]. These results are in line with those of previous studies in which an early improvement after 1 week of treatment with olanzapine or risperidone was a good predictor of treatment response [167-169]

Safety and practicability issues clearly favor a first-line approach with monotherapy because combined treatments are potentially associated with a higher frequency or a greater severity of side effects [166]. However, randomized control trials reported that the addition of an antipsychotic drug in mania despite treatment with lithium or valproate showed greater

rates of acute efficacy than continuation of lithium or valproate as monotherapy [170]. Similar results occurred with a combination of valproate and haloperidol versus haloperidol monotherapy [171]. In line with these results, in clinical practice fewer than 10% of acutely manic patients receive monotherapy and the average number of medications in acutely manic patients is approximately three [172]. This data possibly underlines the difficult in treating “real” patients compared with selected samples in clinical studies.

Moreover the choice of medication strategies is influenced more by the previous

course of illness and history of poor response to treatment rather than symptoms severity

[167]. In fact Szegedi and colleagues (2013) reported that, even though first-episode patients had higher baseline illness severity scores than multiple-episode patients, a greater proportion of first-episode patients were prescribed monotherapy relative to multiple-episode patients.

The clinical practice suggests that patients with acute mania respond differently to treatment and, in many cases, symptoms remission and functional recovery are not reached [12]. In particular the treatment of manic episodes may be difficult when they are complicated by the presence of other features such as depression, psychosis, and anxiety. In a study of untreated patients with acute mania, Swann and colleagues (2002) utilized factor analysis of behavioral rating scale scores followed by cluster analysis, which yielded 4 mania subtypes. The authors names the different mania subtypes anxious-depressive, psychotic, classic euphoria, and irritable. These subtypes were subsequently found to respond differently to treatment with divalproex or lithium. The anxious-depressed subtype had higher distressed appearance scores and was resistant to treatment, the psychotic and classic euphoria subtypes responded to either lithium or divalproex, and the irritable subtype responded better to divalproex than lithium [7].

Lipkovich and colleagues (2008) explored the response to treatment in BD by identifying groups of patients with similar manic symptom improvement profiles. The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis of a double-blind clinical trial in BD patients with a maniac or mixed-episode (n=222). The results showed 4 clusters with different response profiles that could be grouped into 2 contrasting sets of patterns. The first set involved contrasting patients who rapidly improved during the first week of treatment, some of whom either relapsed (Cluster 3) or continued improving (Cluster 2), and a second set contrasting patients who showed less rapid response during the first week of treatment, one group of which did not gain remission (Cluster 1) and the other group continued to improve to remission (Cluster 4). The presence of psychotic features, not being in a mixed episode and the item 10 (appearance) of YMRS were the most significant predictors of slower initial improvement as represented by Clusters 1 and 4 vs. Clusters 2 and 3. Patients in Clusters 1 and 4 differed in their rates of rapid cycling at baseline, 39.1% vs. 56.7%. Interestingly Cluster 4, which had the higher rates for rapid cycling, eventually gained remission. For Cluster 3 vs. 2, the larger number of previous manic episodes and randomization to divalproex treatment were significant predictors of relapse following rapid reduction in symptoms. The similarity between clinical courses for Clusters 1 and 4 and for Clusters 2 and 3 during the first week of treatment and their markedly different response profiles is interesting, and may have implications about the importance of clinical observation early in treatment of patients in order to avert potential relapse. However, the response profiles for the clusters in that study was supported by previous reports. Cluster 4, which was comprised of more psychotic patients, with more severe mania baseline scores, and less severe depressive scores responded to treatment with either divalproex or olanzapine similar to the psychotic mania subtype described by Swann and colleagues (2002). Patients in Cluster 3, who had more severe depressive symptoms at baseline, relapsed within 2 weeks and remained resistant to treatment similar to the anxious-depressed subtype [7]. In addition,

Cluster 3 was characterized by having more prior manic episodes, which has been reported by Welge and colleagues (2004) to be a predictor of poor response [173]. Cluster 2, which responded well to treatment with either olanzapine or divalproex, may share features with the classic euphoria subtype [7, 174]. Finally, Cluster 1 characteristics and response profiles do not appear to share similarities with any of the naturalistic mania subtypes proposed by Swann and colleagues [7, 174].

From the therapeutic point of view, the mixed mania represent a major challenge, especially because this form tends to have a less favorable response to drug treatments and often requires a more complex approach than non-mixed forms [115, 116, 128, 173].

Evidence for available medications to treat mixed manic episodes is mainly based on limited data coming from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) originally including both manic and mixed patients. Usually additional analyses were performed to identify effects in a subgroup of mixed patients. Although this approach has several shortcomings, little evidence is available to delineate a potential differential response between mixed and non-mixed manic episodes.

Unfortunately, there is practically no evidence on how efficacy varies on the basis of the quantitative presence of co-occurring depressive symptoms during mania. In the case of depressive symptoms during mania, Valproate and Carbamazepine [128] has been shown to

be more effective than lithium. The use of atypical antipsychotics is indicated in the most

severe forms and quetiapine [105, 175] and asenapine [140, 176] showed the best

antidepressant profile in respectively in bipolar depression and in mixed mania in comparison with other second generation antipsychotics. Clozapine is probably similar but should be reserved for resistant or intolerant patients [177]. Moreover, although there is no direct evidence for lack of efficacy, the use of typical neuroleptics, especially at a higher

mixed/dysphoric manic states [178].

The currently available data, however, appears not adequately tailored to meet clinicians’ needs, and there is a clear need to conduct well-powered trials, specifically designed to

3.

A

IM OF THE STUDY

In the present study we explored the influence of affective temperaments on the clinical course and functional outcome of a sample of BD patients experiencing a manic episode. The data were collected as a part of a naturalistic, multi-centric, Italian study over an observation period of 12 weeks.

The changes of Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) scores from baseline were evaluated to observe the evolution of various parameters (manic and/or depressive symptomatology, functioning, and quality of life) and to examine the correlations between affective temperaments and the course of BD [123, 179, 180].

During this study we have also investigated the presence of an association between intrinsic (clinical-demographic characteristics and personality traits) and extrinsic factors (childhood trauma and psychosocial characteristics) and affective temperaments.

4.

M

ATERIALS AND

M

ETHODS

4.1. Study design

This was a multi-centric prospective, longitudinal, non-interventional study.

The study duration was 3 months for each patient (5 visits): screening for inclusion in the study and baseline assessment were concomitants; follow-up visits at week 1, 3, 8 and 12 (± 1 week).

Patients could be considered for enrolment in the study when treatment indicated for mania was received in normal practice setting and, in accordance with the decision of the treating psychiatrist, the patient had to initiate or change (excluding dose changes) oral medication for the treatment of mania. The decision to initiate or change medication and the type of medication selected were completely independent of the study, which only observed treatment choices and outcomes, rather than directing treatment. Psychiatric and treatment histories of each patient were recorded.

Participating psychiatrists (or their designees) recorded observational data on a regular basis. However, these observations had to occur only during treatment that was part of the standard course of care. Appointments should not be scheduled for the purposes of data collection. Although patient consent had to be achieved as required by local laws and regulations, data collection did not require any patient intervention beyond usual practice and should not alter the care provided.

Patient privacy was established and maintained throughout the course of the study. Relevant clinical history was recorded. Patients meeting all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were assessed by the YMRS and MADRS for the evaluation of the severity of affective symptomatology [123, 179]. The global severity of manic episode was evaluated by the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Bipolar Illness (CGI-BP), which allowed

determining the degree of change from the immediately preceding phase and from the worst phase of illness [181]. The FAST scale was used to assess the social, occupational, psychological and cognitive functioning [180].

At each visit after baseline (week 1, 3, 8 and 12, ± 1 week), the same psychopathological tools were used to assess symptoms evolution over time. Evaluation of affective symptomatology was evaluated mainly by the YMRS, MADRS and CGI-BP.

At week 12 the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) was used to assess the occurrence of childhood trauma (from 12 years old up) [182].

The Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego brief-version (briefTEMPS-M) was also administered at week 12 to investigate temperamental characteristics (depressive, cyclothymic, hyperthymic, irritable, anxious) [183].

During all the course of the study, any change in drug regimen or doses was recorded, as well as any non-pharmacological treatment.

4.2. Sample

Male or female patients aged 18 or older presenting manic episode in the context of BD I, according to DSM-IV-TR criteria (APA, 2000).

In order to be enrolled, patients had to fulfill the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in in the following paragraphs.

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for this trial, patients had to meet the following documented criteria:

1. inpatients or outpatients with manic episode in the context of a Bipolar Disorder I on the base of the physician evaluation, according to DSM-IV-TR criteria;

2. 18 years of age or older;

3. due to the clinical state of the patient, the treating psychiatrist initiated or changed (this did not include a dose change) treatment for mania with an oral antipsychotic and/or mood stabilizer;

4. in the inpatient facility or in the outpatient setting;

signature of the informed consent as required by local laws and regulations. Exclusion criteria

Patients with any of the following were not eligible for participation: 1. participating in a separate study that had an interventional design; 2. not able to read or understand the informed consent;

3. pregnant or breast-feeding;

4. member of the site personnel or their immediate families. Treatments

The assignment of the patients to a particular therapeutic strategy was not decided in advance by the study protocol and was clearly separated from the decision to include the

patient in the study. The treating psychiatrist according to his/her clinical experience and guidelines made therapeutic choices, in a naturalistic setting. Any treatments were administered according to the recommendations given in the local ethics Committee. Medication use patterns were collected throughout all the course of the study.

4.3. Demographic and other patients measurements

Patients were observed during 12 weeks of treatment indicated for a BD I. For each patient entered in the study, the participating investigator or designee completed an electronic data form via a dedicated, secure website.

Data collected included the following, as done in routine practice:

• Demographic characteristics (gender, birth date, weight, height, education level, current employment, current marital status and current living status)

• Disease characteristics (age at first diagnosis of BD I, duration of current manic episode, age at first disease episode, number of episodes total and per year, polarity of previous episodes, history of delusional symptoms, suicide attempts, alcohol or substance use, age at first treatment, number and duration of hospitalizations and forced treatments, comprehensive collection of previous treatments for current and previous manic episodes with respective efficacy)

• Psychiatric history was recorded both for patient

• Significant medical comorbidities (cardiac, metabolic) and their associated treatment • Measures of symptoms severity (MADRS, YMRS, CGI-BD)

• Measure of social, occupational psychological and cognitive functioning (FAST) • Treatment prescriptions related to bipolar disorder (previous therapy when present

reason for treatment change and new treatment administered at baseline) • Evaluation of temperament traits (briefTEMPS-M)

• Assessment of occurrence of childhood trauma (CTQ).

Diagnostic assessment

The diagnosis of manic episode in BD I was based on psychiatrist evaluation based on the DSM-IV-TR criteria [184].

Symptomatology assessment

Manic symptoms were quantitatively and qualitatively assessed through the use of the YMRS [123], an 11-items scale that carefully investigates the key symptoms of mania, i.e. those that are generally present during all the course of mania. The investigated areas pertained to mood, motor activity, thought disorders, judgment ability, aggressiveness, libido, sleep and general behaviour. The YMRS was specifically created for the evaluation of manic symptoms and their evolution during treatment.

Depressive symptomatology was investigated by the MADRS [179], which was expressly created to be sensitive to the evolution of depressive symptoms over time. The assessment of depressive symptoms is thought to be relevant also during manic phases, since the possible occurrence of dysphoria and switching towards a mixed state. Its 10 items explore depressed mood, inner tension, sleep and appetite disturbances, concentration difficulties, asthenia, inability to feel, pessimistic and suicidal thoughts. In the present study, the scale was administered at baseline, week 1, 3, 8 and 12.

The global psychopathology was evaluated by the use of the CGI-BP [181], a version of CGI that preserves the fundamental assets of the original global rating instrument while focusing on the specific components of BPD. It allows determining a global evaluation in three areas: the severity of the illness, the global improvement and the efficacy index (comparison of the patient’s baseline condition to a ratio of current therapeutic benefit and severity of side effects). In the present study, the scale was administered at baseline, at week 1, 3, 8 and 12.

Functioning assessment