ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Journal

of

Neuroscience

Methods

j ou rn a l h o m epa g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / j n e u m e t h

Basic

neuroscience

Opportunities

for

improving

animal

welfare

in

rodent

models

of

epilepsy

and

seizures

夽

Katie

Lidster

a,∗,1,

John

G.

Jefferys

b,1,

Ingmar

Blümcke

c,1,

Vincenzo

Crunelli

d,1,

Paul

Flecknell

e,1,

Bruno

G.

Frenguelli

f,1,

William

P.

Gray

g,1,

Rafal

Kaminski

h,1,

Asla

Pitkänen

i,1,

Ian

Ragan

j,1,

Mala

Shah

k,1,

Michele

Simonato

l,1,

Andrew

Trevelyan

m,1,

Holger

Volk

n,1,

Matthew

Walker

o,1,

Neil

Yates

p,1,

Mark

J.

Prescott

a,1aNationalCentreforReplacement,RefinementandReductionofAnimalsinResearch(NC3Rs),GibbsBuilding,215EustonRoad,LondonNW12BE,UK bDepartmentofPharmacology,UniversityofOxford,OxfordOX13QT,UK

cInstituteofNeuropathology,UniversityofErlangen,Erlangen,Germany dNeuroscienceDivision,SchoolofBiosciences,CardiffUniversity,Cardiff,UK

eComparativeBiologyCentre,MedicalSchool,NewcastleUniversity,NewcastleUponTyne,UK fSchoolofLifeSciences,UniversityofWarwick,Coventry,UK

gNeuroscienceandMentalHealthResearchInstitute,SchoolofMedicine,CardiffUniversity,Cardiff,UK hUCBPharma,Brussels,Belgium

iDepartmentofNeurobiology,InstituteforMolecularSciences,UniversityofEasternFinland,Kuopio,Finland jNC3RsBoard,GibbsBuilding,215EustonRoad,LondonNW12BE,UK

kUCLSchoolofPharmacy,UniversityCollegeLondon,London,UK lDepartmentofMedicalSciences,UniversityofFerrara,Ferrara,Italy

mInstituteofNeuroscience,MedicalSchool,NewcastleUniversity,NewcastleuponTyne,UK nDepartmentofClinicalScienceandServices,TheRoyalVeterinaryCollege,Hatfield,Herts,UK oInstituteofNeurology,UniversityCollegeLondon,London,UK

pSchoolofBiomedicalSciences,UniversityofNottingham,Nottingham,UK

h

i

g

h

l

i

g

h

t

s

•ReportofanexpertWorkingGrouptoidentifyopportunitiesforrefiningrodentmodelsofepilepsy. •Baseduponasurveyofepilepsycommunity,literaturereviewandexpertopinion.

•Backgroundinformationandrecommendationsprovidedtoimproveanimalwelfare. •Practicalguidanceonrefinementopportunities(e.g.induction,recordings,perioperativecare).

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory: Received9July2015

Receivedinrevisedform1September2015 Accepted8September2015

Availableonline12September2015 Keywords: 3Rs Animalmodel Epilepsy Mouse Rat Refinement Seizure

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Animalmodelsofepilepsyandseizures,mostlyinvolvingmiceandrats,areusedtounderstandthe pathophysiologyofthedifferentformsofepilepsyandtheircomorbidities,toidentifybiomarkers,andto discovernewantiepilepticdrugsandtreatmentsforcomorbidities.Suchmodelsrepresentanimportant areaforapplicationofthe3Rs(replacement,reductionandrefinementofanimaluse).Thisreport pro-videsbackgroundinformationandrecommendationsaimedatminimisingpain,sufferinganddistress inrodentmodelsofepilepsyandseizuresinordertoimproveanimalwelfareandoptimisethequality ofstudiesinthisarea.Thereportincludespracticalguidanceonprinciplesofchoosingamodel, induc-tionprocedures,invivorecordings,perioperativecare,welfareassessment,humaneendpoints,social housing,environmentalenrichment,reportingofstudiesanddatasharing.Inaddition,some model-specificwelfareconsiderationsarediscussed,anddatagapsandareasforfurtherresearchareidentified. Theguidanceisbaseduponasystematicreviewofthescientificliterature,surveyoftheinternational epilepsyresearchcommunity,consultationwithveterinariansandanimalcareandwelfareofficers,

夽 ReportofaWorkingGroupoftheNationalCentrefortheReplacement,RefinementandReductionofAnimalsinResearch(NC3Rs). ∗ Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+442076112279.

E-mailaddress:[email protected](K.Lidster).

1 AllauthorsaremembersoftheNC3Rsworkinggrouponmammalianmodelsofepilepsy(www.nc3rs.org.uk/epilepsy).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.09.007

0165-0270/©2015TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/).

andtheexpertopinionandpracticalexperienceofthemembersofaWorkingGroupconvenedbythe UnitedKingdom’sNationalCentrefortheReplacement,RefinementandReductionofAnimalsinResearch (NC3Rs).

©2015TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Contents

1. Introduction...3

1.1. Background...3

1.2. Workinggroupaimsandscope...4

1.3. Reportaudienceandcontents...4

1.4. Methodology...4

1.5. Limitationsofmethodology...5

2. Animalmodelsusedinepilepsyresearch...5

2.1. Areaofepilepsyresearch...5

2.2. Speciesandmodelsused...5

2.3. Choiceofanimalmodel ... 5

3. Generalprinciplesforrefinement...6

3.1. Considerationsinthechoiceofanimalmodel...6

3.2. Inductionprocedures...8 3.3. Invivorecordings...8 3.4. Perioperativecare...9 3.5. Welfareassessment...11 3.6. Humaneendpoints...12 3.7. Socialhousing...13 3.8. Environmentalenrichment...14

3.9. Reportinganddatasharing...15

4. Model-specificwelfareconsiderations...15

4.1. ModelsdependentoninitialSE...18

4.2. ModelsnotinvolvingSE...18

5. Discussionandconclusions...19

5.1. Datagapsandfutureresearch...19

5.2. Recommendations...19

Conflictofintereststatement ... 20

Acknowledgements ... 20

AppendixA. Supplementarydata...21

References...21

1. Introduction 1.1. Background

Epilepsy(seeGlossary)isoneofthemostcommonserious neu-rologicaldiseases. It affects anestimated 1% ofthe population, whichequatestoabout60millionindividualsworldwide(England etal.,2012).Epilepsypatientsexperiencedebilitatingseizures(see Glossary)associatedwithabnormalelectricalactivityinthebrain. Seizurestypicallylasttensofsecondstoafewminutes,and usu-allyareseparatedbyprolongedinterictalperiods.Epilepsy does more than cause seizures, however:depending on the type of epilepsyitmaybeassociatedwithincreasedmortality(Sillanpää andShinnar,2010),transientpostictalbehaviouralchangesanda rangeofcomorbiditiesincludingcognitiveimpairments(Inostroza etal.,2011),anxiety(Mazaratietal.,2009;EppsandWeinshenker, 2013)andsystemiceffects.Atleast15differenttypesofseizures and30epilepsysyndromeshavebeenidentifiedacrossthe life-span(Bergetal.,2010).Thediversityofclinicalepilepsieshasled toclassificationbytheInternationalLeagueAgainstEpilepsy(Berg andCross,2010;BergandScheffer,2011).

There remain many unresolved clinical issues in epilepsy (BaulacandPitkänen,2008;Galanopoulouetal.,2012).First,none oftheanti-epilepticdrugsinclinicalusecanpreventdevelopment ofepilepsyin caseswhere theprecipitatingepileptogenicevent isidentifiable.Second,pharmacologicaltherapyremains unsatis-factory:onethirdofthepatientstreatedwithantiepilepticdrugs

continuetoexperienceseizures.Inpatientsinwhomseizuresare wellcontrolled,drugsmayexertdebilitatingsideeffectsand,in somecases,refractorinesstotheirtherapeuticeffectsmaydevelop. Third,disease-modifyingtherapiesareneeded:antiepilepticdrugs donotpreventtheprogressionofthedisease,andthereisalackof therapiesthatcanameliorateorpreventtheassociatedcognitive, neurologicalandpsychiatriccomorbidities,ortheepilepsy-related mortality.

Thereisanincreaseddemandforanimalmodelsthatadequately recapitulatehumanepilepsy,tofurtherunderstandthe mecha-nismsunderlyingepileptogenesisinthedifferentformsofepilepsy (LöscherandBrandt,2010)andtodevelop therapiestoprevent theepileptogenicprocess,bettertreatcomorbiditiesandtreatdrug resistantepilepsy(BaulacandPitkänen,2008;Brooks-Kayaletal., 2013).However,animalmodelsofepilepsyandseizures,mostly involvingmiceandrats,havethepotentialtocausepain,suffering, distressandlastingharm1totheanimalsinvolved.Thiscanbeasa

consequenceofthemethodofinductionoftheepilepsysyndrome, comorbiditiesandassociatedanimalhusbandrypractices,acuteor chronicpost-ictalsequelaeandinstrumentation,andprocedures formonitoringepileptiformactivity.Hencesuchmodelsare typ-icallyclassifiedinlegislation(e.g.theEuropeanDirectiveonthe protectionofanimalsusedforscientificpurposes(2010/63/EU))

asmoderateorsevereprocedures;similarregulationsapply else-where.Thereisthereforeaneedforclearguidanceontheiruseand refinement,inordertominimiseanysuffering,whichisimportant forethical,scientific,andlegalreasons.

1.2. Workinggroupaimsandscope

The National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reductionof AnimalsinResearch(NC3Rs) isascientific organi-sationestablished bytheUnited Kingdom(UK) Government in 2004toleadthediscoveryandapplicationofnewtechnologiesand approachestoreplace,reduceandrefinetheuseofanimalsfor sci-entificpurposes.In2013theNC3RsconvenedanexpertWorking Groupwiththefollowingtermsofreference:

1.Toreviewandsummarisecurrentuseofmammalianmodelsof epilepsy.

2.Toidentifytheanimalwelfareissues. 3.Torecommendopportunitiesforrefinement.

4.Toassessandbalancethebenefitsofepilepsyresearchagainst theharmstotheanimalsinvolved.

5.TopublishthedeliberationsoftheWorkingGroupina peer-reviewed paper and promote the group’s recommendations withintheinternationalepilepsyresearchcommunity.

MembershipoftheWorkingGroupcomprisedneuroscientists, neurologists, epileptologists, neuropathologists, neurosurgeons, animal welfare scientists and veterinarians fromacademia and thepharmaceuticalindustry,withexperiencecoveringarangeof epilepsyresearchareas,includingchronicandacuteanimalmodels. It wasnot withinthe scopeof theWorking Groupto iden-tifyopportunitiesforreplacementofanimalmodelsofepilepsy; thesehavebeendiscussedandpublishedpreviously(Cunliffeetal., 2014).NordidtheWorkingGroupinvestigateandassessthe pre-dictivevalueofthevariousanimalmodels,sincethisoverlapswith thegoaloftheJointInternationalLeagueAgainstEpilepsy(ILAE) andAmericanEpilepsySociety(AES)TranslationalResearchTask Forcetooptimiseandacceleratepreclinicalanti-epileptictherapy (Galanopoulouetal.,2013;Simonatoetal.,2014).Moststudiesin animalseizure/epilepsymodelsareinpost-weanedanimalsand thereisanaturalbiastowardsthesemodels.TheWorkingGroup recognisesthe impactthat agecanhave onwelfare issues and wherethereisevidenceoracceptedbestpracticeinpre-weaned animals,ithasbeenincluded.

1.3. Reportaudienceandcontents

TheWorkingGroup’sreportprovidesbackgroundinformation andrecommendationstogiveresearchers,veterinarians,animal carestaff,regulators,andlocalethicaloranimalcareanduse com-mitteesthetoolstorefinetheuseofanimalmodelsofepilepsyand seizures.Thefocusisrodentmodels,butmanyoftheprinciplesfor refinementapplytootherspecies.Generalprinciplesaregivenin Section3.Moredetailedrefinementsforcommonlyusedmodels arecoveredinSection4.Wenotethatmanymajorepilepsygroups alreadyworktohighethicalstandards;ouraimistopromotebest practiceaswidelyaspossible.

1.4. Methodology

Thefoundation of theWorking Group’s reportwas a litera-turesearchconductedusingthePubMedandGo3Rsdatabasesand combinationsofthekeywordslistedinTable1.Thesekeywords werealsousedtoscreenfor informationin thebookModels of SeizuresandEpilepsy(Pitkänen etal.,2006).Titlesandabstracts

Table1

Keywordsusedintheliteraturesearchrelatingtopossibleadverseeffectsand refinementsinanimalmodelsofepilepsy.

Epilepsyterms

Convulsion;epilepsy;seizure;statusepilepticus

Possibleadverseeffects Possiblerefinements Aggression;anxiety;dehydration;

excessive;fighting;infection; locomotoractivity;pain;mortality; weightloss

Analgesia;antibacterial;antibiotics; enrichment;grouphousing;heating; fluids;food;post-operativecare; refinement

Table2

Levelsofevidenceandgradesofrecommendation.Tablebaseduponascheme pro-posedpreviously(Prescottetal.,2010)andadaptedfromtheNationalInstitutefor HealthandCareExcellence(NICE)guidelines(EcclesandMason,2001).

Levelof evidence

Typeofevidence Gradeof

recommendation I+ Appropriatelydesigned,controlledtrials,

withalowriskofbias(e.g.objective assessmentofthedata)

A

I Appropriatelydesigned,controlledtrials II+ Case-controlorcohortstudies,withalow

riskofbias(e.g.objectiveassessmentof thedata)

B

II Case-controlorcohortstudies

III Casereports,caseseries C IV Expertopinion,formalconsensus D

ofthepapers retrievedfromthesearchwerereviewedfor

rele-vance.ThosenotrelevanttotheaimsoftheWorkingGroupwere

excluded.Fulltextcopiesof142articlespublishedbetween1970

and2014wereobtainedandscreenedforinformationonadverse

effectsandrefinements inanimalmodelsofepilepsy.The

qual-ityofthereportedstudieswasassessedaccordingtothecriteria

inTable2.Aseparate,smallerliteraturesearchwasconductedto examinereportingoftheuseofanalgesiainstudiesutilisingrodent modelsofepilepsy(seeSection3.4).

Aqualitativesurveywasconductedamongstresearchers work-ingwithanimalmodelsofepilepsyidentifiedfrompublications inthefield.Aquestionnairewasemailedto322researchersin28 countries.Researcherswereinvitedtoparticipateanonymouslyin thesurveyandaskedtoanswer12 questions(seeAppendix1), withtheaimtoidentifywhich mammalianmodelsareusedin epilepsyresearchandtodefinebestpractice.Thesurveyexcluded animalsusedforthegenerationofinvitromodelsofepilepsyand seizures.Therewerethreeperiodsofdatacollection(July 2013, November2013andMarch2014).Atotalof60surveyresponses coveringabroadrangeofanimalmodelswerereturnedfor anal-ysis.Thisisasatisfactoryresponserateforaqualitativesurvey. Thesurveyresponsesrepresentedawidegeographicaldistribution withresponsesfrom20countriesinEurope,NorthAmerica,South America,AsiaandAustralia.

Inadditiontothesurvey,betweenFebruaryandApril2014,KL conductedinterviewswiththeNamedVeterinarySurgeons(NVS) andNamedAnimalCareandWelfareOfficers(NACWO)atfourUK universitieswithresearchgroupsusingrodentmodelsofepilepsy. TheWorkingGroup’srecommendationsweregradedaccording tothelevelsofevidencedefinedinTable2,followingtheapproach previouslyadopted byPrescott et al.(2010).Recommendations weregraded(A–D)accordingtothehighestlevelofevidence(I–IV). Wherethereisdirectsupportingevidence,theindividualreference andlevelofevidenceisindicatedwithintherecommendation.

1.5. Limitationsofmethodology

Ingeneral,thereisapaucityofpublishedinformationonboth theanimalwelfareimplicationsofanimalmodelsofepilepsyand opportunitiesfortheirrefinement.Whereevidencewaslacking, theWorkingGroupbaseditsrecommendationsonresponsesfrom thesurveyandtheexpertopinionandpracticalexperienceofits members(LevelIVevidence).

2. Animalmodelsusedinepilepsyresearch

ThesurveyenabledtheWorkingGrouptoobtainanoverview ofthecurrentareasofepilepsyresearch,thetypesofanimalmodel usedandtheirlimitations.

2.1. Areaofepilepsyresearch

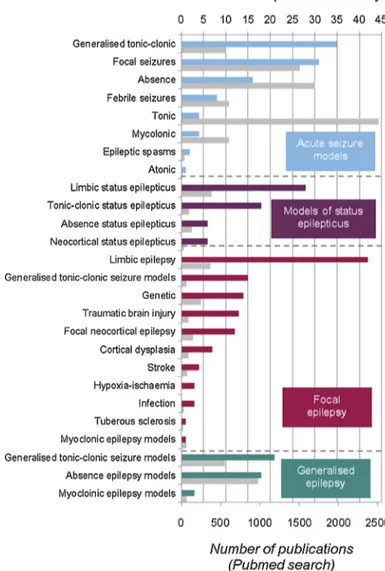

Toensuretheresultsofthesurveywererepresentativeofthe epilepsyresearchcommunity, researcherswereaskedin which area(s)ofepilepsyresearchtheyworked;areasweredividedinto acuteseizures,focalepilepsy,generalisedepilepsy,status epilepti-cus(SE)(seeGlossary)andgeneticmodelswithepilepsyaspart of the phenotype. Survey responses were found to bebroadly representativeofcurrentepilepsyresearchareasreportedinthe publishedliterature(upto May2015), withtheexception of a fewareaswhichwereunder-represented(e.g.tonicseizures)or over-represented(e.g.generalisedtonic–clonicseizuresandlimbic epilepsy)(Fig.1,Appendix2).

2.2. Speciesandmodelsused

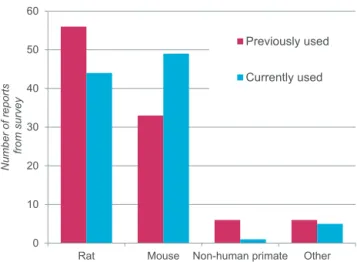

Researcherswereaskedwhichanimalmodel(s)theycurrently usedandhavepreviouslyused.Atrendtowardsincreaseduseof micewasidentified;increasingfrom33%oftotalreportsof ani-malspreviouslyusedto49%ofanimalscurrentlyused(Fig.2).This islikelytobeareflectionofthegrowingincreaseinavailability ofgenetically-modifiedmousemodels;almost400genes associ-atedwithseizurephenotypes inmicearelistedontheJackson Laboratorydatabase(http://www.jax.org/).

Atrendtowardsdecreaseduseofnon-humanprimatemodels wasalsoidentified.Publishednon-humanprimatemodelsinclude themacaquemodelofmesialTLEwithkainicacidinjection(Chen etal.,2013),themarmosetmodelofTLEwithpilocarpine injec-tion(Perez-Mendesetal.,2011)andnaturally-occurringepileptic baboons(Szabóetal.,2012).Giventheseriousethicalandanimal welfareissuesraisedbytheuseofnon-humanprimates2in

inva-siveresearch,theiruseshouldbelimitedtocaseswherethereis strongjustificationonscientificand/ormedicalgrounds(Prescott, 2010;Batesonetal.,2011).

Anoverview of therange of animal modelsreported inthe survey, categorised into acute seizure models, chronic models withhighpropensityforinducedseizuresorepileptogenesis,and chronicmodelsofepilepsy,ispresentedinTable3(classification devisedbySimonatoetal.,2014).

Whereresearchershadceasedtouseaparticularrodentmodel, theywereaskedthereasonsforthis.In57%ofcasesthiswasdueto achangeinstrategicdirection,in14%duetofinancialreasons,and in11%duetolackoftranslationtotheclinic.Otherexplanations providedincludedtheseverityofthemodel(7%)anditssubsequent burdenonanimalwellbeing,highmortality(3%)andhighlevelsof variabilityinthemodel(1%).

2Foradviceonrefiningnon-humanprimateuseandcare,seewww.nc3rs.org.uk/

welfare-non-human-primates.

Fig.1. Areasofepilepsyresearchrepresentedinthesurvey.Colouredbarsare representativeofthenumberofrespondentsinthesurveyconductingresearch ineachareaofepilepsyresearch:acuteseizuremodels(blue),modelsofstatus epilepticus(purple),focalepilepsy(red),andgeneralisedepilepsy(green).Greybars arerepresentativeofthenumberofpublicationsinthescientificliteraturebased uponaPubMedsearchconductedusingsearchtermsdetailedinAppendix2.(The searchmethodsusedmayresultinanoverestimationofthenumberof publica-tionsrepresentingaseizuretype.Forexample,searchresultsfor“tonic”mayresult inpublications,whichtheprimaryaimofthestudywasnottoinvestigatetonic seizuresbut“tonic”mayhavebeenusedintheabstracttodescribefeaturesofother typesof(e.g.generalizedtonic–clonicorfocaltonic–clonic)).(Forinterpretationof thereferencestocolorinthisfigurelegend,thereaderisreferredtothewebversion ofthisarticle.)

Researcherswereaskedtheageofanimalsused.Theagerange variedaccordingtothemodel;forexample,geneticmodelswere commonlyusedatveryyoungages(postnatalday0topostnatal day10).Commonlyusedinducedmodels,suchaskainicacidand pilocarpine,variedfromusingyounganimals(postnatalday10)to adults.Thevariationinagesreflectsthedifferentaspectsofepilepsy andseizuresbeingresearchedandtechnicalconsiderations(e.g. easeofpatchclampingorcalciumimaging).

2.3. Choiceofanimalmodel

Researcherswereaskedwhatfactorstheyconsideredwere lim-itationsonthechoiceofanimalmodel(summarisedinFig.3).High mortalityrates and variability betweenanimals werethe most commonlimitations,alongwithhighfinancialcost.Notethatmany ofthelimitationsarerelatedandhavethepotentialtobeaddressed

Table3

Animalmodelsreportedinsurvey(tableformatadaptedfromSimonatoetal.,2014).

Acuteseizuremodels Chronicmodelsofhighpropensityforinducedseizuresorepileptogenesis

Electrical Chemical Genetic Induced

6Hzsimulation Gamma-hydroxybutyrate(GHB) D2Rknockout Kindling(corneal,hippocampal,amygdaloidal,PTZ) MaximalElectroshockSeizure(MES) Pentylenetetrazole(PTZ) En2knockout Hypoxiaand/orischemia

Modelsofepilepsy

Genetic Induced

Electrical Chemical CNSinsult

5-HT2cknockout DBA/2mice

GeneticAbsenceEpilepsyRatsfrom Strasbourg(GAERS)

Geneticbenignfamilialneonatal-infantile seizures(BFNI)

Geneticgeneralisedepilepsywithfebrile seizures(GEFS) Kcna1-nullmouse Lethargic LGI1knockout NaV1.1knockout Stargazer Scn1aknockin Sv2aknockout Tottering TGFandTGFRtransgenic WistarAlbinoGlaxoRatsfromRijswijk (WAG/RiJ)

Amygdalastimulation Perforantpathstimulation

Cobaltcortical

Kainicacid(intraamygdala, intrahippocampal,intraperitoneal, subcutaneous) Lithium-pilocarpine Pilocarpine Penicillin Tetanustoxin Albumin Bloodbrainbarrier disruption

Fluidpercussion(traumatic braininjury)

Hypoxia Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy Maternalteratogenmodel ofautismandepilepsy Stroke 0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Rat Mouse Non-human primate Other

Num ber of reports from survey Previously used Currently used

Fig.2.Speciesofepilepsymodelsreportedinthesurvey.Otherspeciesincludes naturally-occurringepilepsyincats,dogs,pigeonsandpigs.

bytakingadvantageoftherefinementopportunitieshighlightedin

thisreport.

Researcherswereasked“Doyouthinkthelimitationsof

ani-malmodelsarerestrictingprogressinepilepsyresearch?”48%of

researchersconsideredthat theywererestricting progress,27%

consideredthattheywerenot,and25%wereunsure.Onereason

givenfortheformerviewwasdifficultyinrecapitulatingspecific

aspects ofthe humancondition.Re-assessmentof translational

approachesiscurrentlybeingundertakenbytheILAE/AES

Trans-lationalResearchTaskForce(Galanopoulouetal.,2013;Simonato

etal.,2014).

3. Generalprinciplesforrefinement

Theliteraturesearch,surveyandinterviewsidentifiedarange ofrefinementopportunitieswhich aredescribedbelow, supple-mentedbytheexpertopinionandprofessionalexperienceofthe WorkingGroupmembers.

3.1. Considerationsinthechoiceofanimalmodel

Thechoiceofmodelwilldependonthetypeofepilepsybeing modelled,thescientificquestionbeingasked,andtheneedto min-imiseanimalsufferingandnumbers(Pitkänenetal.,2006;Grone andBaraban,2015).Modelsshouldrepresentkeyfeaturesofthe correspondingdisease,butshouldnotnecessarilystrivetobe iden-tical.Forinstance,testingmethodstocontrolseizuresmayneeda

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Regulatory approval

Large group sizes

Animal welfare

Labour intensive

High financial costs

High variability High mortality

Strongly agree Agree Neither agree or disagree Disagree Strongly disagree

Fig.3. Limitationsonchoiceofanimalmodel.ReasonsprovidedbysurveyrespondentsinresponsetoQuestion9.“Doyouconsiderthefollowingtobelimitationsonyour choiceofanimalmodel?”.

higherrateofseizuresthanthatwhichoccursinthetypical clini-caldisease,becausetestingadecreasefromextremelylowratesis impracticalinthecurrentscientificsettingsandtimelines.

Modelscanbedistinguishedbetweenacuteandchronic,focal andgeneralised,acquiredandgenetic.Acuteanimalmodelsuse chemical, electrical or physical stimulation to trigger epileptic activityand have beenextensively usedtodiscover newdrugs but theyhave not ledtothedevelopment ofdrugs that target eitherthegenerationor themaintenance of theepilepticstate. Acuteanimalmodelsmodelsymptomaticseizuresinnormalbrain, while chronicepilepsy resultsfrom pathological structural and functionalchangesinthebrain.Chronicmodelshavebeen recom-mendedformanykindsofepilepsyresearch(Stablesetal.,2003) includingscreening systems (e.g.NIH AnticonvulsantScreening Program(www.ninds.nih.gov/research/asp/index.htm)andtarget validationorproof-of-pharmacologyformechanismsthatcannot betestedwithacuteseizuremodels(i.e.anti-inflammatory thera-pies)(Löscheretal.,2013).

Behaviouralcomorbiditiesobservedintheinterictalperiod(e.g. cognitiveimpairments,hyperactivityanddepression(Barkmeier and Loeb, 2009; Tabbet al., 2007)) are an integral partof the epilepsysyndromeandlegitimatesubjectsforinvestigation. How-evertheymayalsoimpactontheanimals’welfare,inwhichcase researchersandethicaloversightcommitteesmustcarefullyweigh thepotentialresearchbenefitsandtheharmstotheanimals.A roadmapforrationalselection,implementationandinterpretation ofbehaviouralassaysinanimalmodelsofepilepsyhaspreviously beendefined(HeinrichsandSeyfried,2006).

Oneofthemajorwelfareconcernsforthoseworkingwith ani-malmodelsofepilepsyistheexperienceoftheanimalduringand betweenseizures.Itcanbedifficulttoappreciatetheexperience ofanimalsduringseizures;theonlysurrogateistheexperienceof epilepsypatients.Itisimportanttorealisethattheexperienceof witnessescanbeverydifferentfromthatofthepatients(e.g. con-vulsionscanbeverydistressingtowitness,butsincetheperson havingtheconvulsionhasmarkedlyreducelevelsof conscious-ness,theyexperiencenodistressduringtheseizure,Englotetal., 2010).Observationsinratshaveshowndepressedcorticalfunction duringfocalseizures(Englotetal.,2008);refinementofthechoice ofmodelsolelyonthefrequencyorintensityofseizureactivity maynotbeappropriate.Thepriorityshouldbetoobjectivelyassess theexperienceoftheanimalandthinkcriticallyaboutwhatisthe relevantmodelforthespecificresearchquestionandtheclinical relevance.Increasinglymoresophisticatedapproachestoassessing adverseeffects(e.g.pain,distress,anxiety)inlaboratoryrodents arebeingdevelopedandresearchteamsshouldbeadoptedwhen possible(e.g.bysearchingtheliteratureandNC3Rswebsitewww. nc3rs.org.uk).

Assessmentofanimalwelfare,andbalancingharmstoanimals againstthepotentialbenefitsoftheresearch,mustaddressthe wholeepilepsysyndrome,notjustoneoftheclinicalsigns.The periodsbetween seizuresare essential for animalsto maintain themselvesin goodconditionandallowrecoveryfromseizures. Therecurringepisodicnatureofepilepsy,andtherepeated proto-colsthatmaybeusedtoinducetheepilepticstate,meansthatthe frequencyofadverseeffects,aswellastheirintensityandduration, mustbeincludedintheharm-benefitanalysis.Ajudgmentneeds tobemadeaboutwhatisacceptableintermsofthetype,duration, intensityandfrequencyofseizures,recoverytimeandthelevelof sufferingfollowingtheinitiationofseizures.

Recommendations:

1.A search of thescientific literatureshould becarried out to ensuretheanimalmodelchosenis scientificallyrelevant,the

leastseveremodelforthescientificpurpose,andthatany model-specificrefinementopportunitiesareidentified(GradeD). 2.Assessmentoftheharmstoanimalsandbalancingtheseagainst

thepotentialbenefitsof theresearch,shouldtakeaccountof thelifetimeexperienceoftheanimalsandthewholeepilepsy syndrome(notjust seizures).Thegreater theanimalwelfare cost,thegreaterthestrengthofjustificationneededinterms ofscientificand/ormedicalbenefit(GradeD).

Choiceofstrain:Rodentmodelsareusedforstudyingthe cel-lularandneuralnetworkmechanismsunderlyingepilepsy.Rodent strainscandifferinseizuresusceptibility(McKhannetal.,2003;

McLin and Steward, 2006; Frankel, 2009; Schauwecker, 2011),

effectsofantiepilepticdrugs(LeclercqandKaminski,2014),aswell astheconsequencesofseizureactivity(Schauwecker,2011).For example,theuseofC57BL/6 ishamperedbyits lowsensitivity toseizureinduction(Mülleretal.,2009;Bankstahletal.,2012); aproblemaddressedbyback-crossingwithotherstrains.Mouse genetic backgrounds play a crucial role in genetically-modified phenotypesandthesusceptibilityofthesestrainstoseizuresand neuropathologicalconsequences(Schauwecker,2011).Itis,thus, importanttoensurethatthegeneticbackgroundiscontrolledto avoid‘genetic’driftandappropriatewild-typelittermatecontrols aregeneratedfromthesamecolony.

Choiceofbreeder:Whenobtaininganimalsfromcommercial breeders,thechoiceofthebreederisacriticalfactor.Itwasrecently demonstratedthatadultfemaleWistarratsfromdifferentbreeders varyinanxiety-likebehaviour,seizuresusceptibilityand epilepto-genesisinthekindlingmodeloftemporallobeepilepsy(Honndorf etal.,2011).Ahighermortalityrateafterpilocarpineinjectionwas observedinC57BL/6micedependingonthesupplier(Borgesetal., 2003).Decisionsaboutappropriatecommercialcoloniesusedfor biomedicalresearchshould,therefore,betakenwithcare.

Choice of age: Seizure susceptibility and manifestation of epilepsies can be age-dependent. Some types of seizures and epilepsiesoccurinneonatesand infantsand arenot presentin adults(Mareˇs,2012;Wasterlainetal.,2013)orviceversa(Sperber et al., 1999). Since brain function alters during development (e.g. neurotransmission, neuronal properties and connectivity (Galanopoulou and Moshe, 2011), the age of animals is likely to affectmany factors suchas sensitivity to chemoconvulsants (Wozniaket al., 1991)and kindling (Cilio etal., 2003), seizure latencyandintensity(PiersonandSwann,1988;Thompsonetal., 1991), mortality (Blair et al., 2009) and behavioural, patho-physiological and pharmacological responses to anticonvulsant (Stafstrometal.,1993;Shettyetal.,2012;Mareˇs,2014).

Choice of sex: Gender differences are emerging amongst sometypesofepilepsies(Galanopoulou,2014).Femalesaremore susceptible to epilepsies such as juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

(Camfieldand Camfield,2009) and childhood absence epilepsy

(Panayiotopoulos,2007)whilstmalesaremoresusceptibletoWest orDravetsyndromeandchildhoodepilepsywithcentrotemporal spikes(Panayiotopoulos,2007).

Sex hormonesmay alsoinfluence thetiming and frequency of certain seizures, as occurs in catamenial epilepsy (Koppel

and Harden, 2014). In animal models involving immature and

adultanimals,sexhormonesand neurosteroidsaffectsignalling pathways and brain regions regulating seizure initiation and maintenance(ScharfmanandMacLusky,2014).Theexpressionof functionofnumeroussignallingpathwaysandtheanatomy, con-nectivityorfunctionofbrainnetworksinvolvedinseizurecontrol alsoexhibitsexdifferencesthat mayaffectthesusceptibilityto seizures,theirconsequencesorresponse todrugs(Giorgietal., 2014;Akmanetal., 2015).Antiepilepticdrugtargetsas wellas pharmacokineticand adverseeffects of antiepilepticdrugs may beaffectedbygender(Peruccaetal.,2014;Pitkänenetal.,2014).

Mostpreclinicalstudiesareperformedonadultmales(Pitkänen etal.,2014),possiblyduetotheconfoundingcontributionsofthe oestruscycleonseizuresusceptibility(Scharfmanetal.,2005);but thereareplanstoaddresstheimbalanceofsexacrossbiomedical research(ClaytonandCollins,2014).

Recommendations:

3.Variationsinthestrain,geneticbackground,source,ageandsex ofanimalscaninfluenceseizuresusceptibilityandmortality(e.g. GradeBforstrain;Schauwecker,2011,LevelII;GradeAforage: Thompsonetal.,1991,LevelI,PiersonandSwann,1988,LevelI+; GradeAforsex;ScharfmanandMacLusky,2014,LevelII;Grade Aforsource;Borgesetal.,2003,LevelI).Thevariabilityshouldbe takenintoconsiderationwhendesigningandconductingstudies andadequatemeasurestakentoreduceexperimentalbias.The strain,source,ageandsexofanimalsusedinstudiesshouldbe consistent,andreportedinpublications.

4.If using genetically-modified mice, the genetic background shouldbecontrolledforandappropriatelittermatecontrolswith thesamegeneticbackgroundshouldbeused;forexample,use age-matchedwild-typelittermatesascontrols(GradeA;Bourdi etal.,2011,LevelI).

5.Giventheevidenceforsex-specificeffectsonepileptogenesis, considerationshouldbegiventousinganimalsofbothsexes. Iffemalesareused,theimpactoftheoestruscycleonseizure susceptibilityneedstobeconsidered(GradeA;Scharfmanetal., 2005,LevelI).

3.2. Inductionprocedures

Proceduresleadingtotheinductionofseizuresand/orepilepsy shouldbetailoredtoreachthescientificendpointeffectivelywhilst limitingsuffering andmortality.The surveyreflects the impor-tanceoftheinductionperiod,whichshowedofthe31respondents reportinghighmortalityasanadverseeffect,90%(28/31)reported highmortalityduringtheinductionphase.

Thestatus-inducingagent,itsdose,itsrouteofadministration andSEdurationallcanaffectbothmortalityandreliabilityof pro-gressiontochronicepilepsy,asdiscussedinmoredetailinCuria etal.(2008).Itisimportanttodetermineabalancebetween min-imisingmortalityandinducingthechronicepilepsymodel.More detailonrefinementofspecificinductionmethodsisgivenin Sec-tion4,Model-specificrefinements.

Long-termepilepsystudiesinvestigatingtheefficacyof anti-epilepticdrugsonspontaneousseizuresmayrequirelong-term continuous administration of drug compounds. The choice of deliverymethodshouldbechosentoalloweffectivedrug concen-trationlevels(Löscher,2007),whilsttakingintoconsiderationthe potentialadditionalstresstotheanimal.Theadvantagesand dis-advantagesofdifferentroutesofadministrationofanti-epileptic drugsinrodentsissummarisedinLöscher,2007.Refinementof theadministrationprotocol,forexample,administrationofdrug orallyinfoodorwaterprovidesanon-invasive,lessstressful alter-nativetorepeatedintraperitonealinjectionsandismorerelevant tothehumansituation(Grabenstatteretal.,2007;Alietal.,2012). Forgeneraladviceonrefiningproceduresforthe administra-tionofsubstancestolaboratoryanimals(e.g.considerationofthe choiceofroute,dosingvolumeandfrequency,andphysiochemical propertiesofthesubstance)seeMortonetal.(2001)andthe NC3Rs-funded Procedureswith Carewebsite3. Use ofappropriate and

3 ProcedureswithCareofferspracticaladviceonthemanualskillsrequiredfor

administrationofsubstancestomiceandrats,includinghigh-definition instruc-tionalvideos:www.procedureswithcare.org.uk.

skilledhandlingtechniquesisessentialtoavoidanxietyandstress responsesintheanimals,whichcanleadtodefensiveaggression, difficultiesinperformingsubsequentproceduresand unwanted variationinexperimentaldata.Handlingmicebythetailinduces aversionandhighanxiety,towhichmicedonotreadilyhabituate, andgenerallyshouldbeavoided(HurstandWest,2010;Gouveia andHurst,2013).

Recommendations:

6.Proceduresleadingtotheinductionofseizuresand/orepilepsy shouldbetailoredtoreachthescientificobjectiveseffectively whilstminimisingharmsandmortality(GradeD).

7.Researchpersonnelshouldbeadequatelytrainedandcompetent inthemanualskillsforappropriatehandlingandrestraintof animalsfortheadministrationofsubstances.Pickingupmice bythetailshouldbeavoidedasthisinducesaversionandhigh anxiety;animalsshouldbepickedupbyanon-aversivemethod (e.g.handlingtunnelsorcupping)(GradeA;GouveiaandHurst, 2013),LevelI+).

3.3. Invivorecordings

Thediagnosticfeatureofepilepsyisrecurringseizureswhich, according tothe ILAE definition, are due to abnormally exces-sive and/or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain (Fisher etal.,2005).Seizuresareoftenassociatedwithmotorsigns,which provideendpointsforclassicalacutedrugscreeningmodelssuch asthehighdosepentylenetetrazole(PTZ)andthemaximal electro-shock(MES)models,andformanyacutemeasurementsofseizure susceptibility.Detectingspontaneousseizuresinchronicmodels needslongterm recording.Severalapproaches are used,either aloneorincombination.Videorecordingorothermeasurements such as micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS), can detect movementsassociatedwithseizures(Sunderametal.,2007). Auto-mated observational systems (e.g. Van de Weerd et al., 2001) can be used to analyse the behavioural profile of animals fol-lowing seizure induction (Riljak et al., 2014)and methods are currentlybeingdevelopedtoallowautomatedrecordingsinthe homecageenvironment4.Electrophysiologicalrecordingprovides

moredirectdetectionofseizures,andisparticularlyimportantfor thoseseizureswithnoorminimal motorconsequences; video-EEGmonitoringshouldbeusedtoidentifyseizureswithnomotor symptoms(Arcierietal.,2014).Inadditiontothesemeansof mon-itoringseizureactivity,intracerebralcannulationfordrugdelivery orsampling,aswellasopticalfibresforoptogeneticillumination, whichcanbecoupledwithrecordingandstimulation(“optrodes”) canbeusedtomonitorandinfluenceseizureactivity.The consid-erationsdescribedbelowapplytothesetechniques.

The main welfare issues to be taken into consideration for chronicelectrophysiologicalrecordingaretheexperimentalsetup (tetheredsystems or radiotelemetry), electrode properties (e.g. physical dimensions, location and logistics of device), surgical implantationofelectrodes(e.g.infection,post-operativerecovery) andmaintenanceofchronicelectrodes(e.g.freedomofmovement, cagesize).Adetailedaccountofthetechnologyisbeyondthescope ofthepaperbutthereaderisreferredtoWeiergraberetal.(2005). Experimentalsetup:Datatransmissioncanbeachievedusing eitherumbilicalcables(tethers)orradiotelemetry.Tethered sys-tems constrain movement. Torque on the headmount can be minimisedbytheuseofsliprings(swivelcommutators),reducing theriskofinjurytotheanimal.Thecombinedweightofthe head-mount,plugandcablecanbemanagedbycarefullyadjustingthe

4NC3RsfundedCRACKITchallenge‘RodentLittleBrother’https://www.crackit.

lengthofthetetheringcable,orbyuseofacounterweightorspring toadjustthecabletofollowmovementsofthehead.Careful atten-tiontobothverticaland rotationalforcescanallowcontinuous recordingforweeks(Dohenyetal.,2002).

Radiotelemetryavoidstetheringwiresandthereforeallows ani-malstomovefreely,whichhasbenefitsforbehaviouralstudies, animalwelfareandcansimplifylonger-termrecording(Bastlund etal.,2004;Weiergraberetal.,2005;Williamsetal.,2006).The developmentofsuchdevicesshouldinclude evaluationof their impactontheviabilityofadjacenttissues.Batterylifeisakeyfactor, particularlyforstudiesonseizurefrequencyorondisease progres-sion.Recordingfromearlypost-natalanimalsismorechallenging (Zayachkivskyetal.,2013).

Devicedimensionsandlocations:Thephysicalsizeandweight ofdevicescanimpactonthewelfareoftheanimal.Devicesshould beaslightaspossibleandpositionedappropriatelytoallowthe ani-malfreemovementtoperformitsnormalbehaviours,particularly toeat,drinkandgroom(Mortonetal.,2003).Itisdifficulttodefine anexactweightlimit.TheexperienceoftheWorkingGroupisthat devicesof5–10%ofbodyweightappeartobetolerated,although therearenopublisheddatatosupportthis.

Devices can be mounted in the locations listed. In general, implanteddevicesshouldbepositionedawayfromtheincision(i.e. notdirectlyunderthesutures).

䊏Headmounted—Thisismostcommonwithtetheredsystems andsomeradiotelemetrysystems.

䊏Subcutaneous—Ifradiotelemetrydevicesaresmallenoughthey canbeimplantedsubcutaneouslywithwirestunnelledtothe recordingsites.Theirsize,weightandlocationshouldnotplace excessivestrainontheskinormusculoskeletalsystem. Differ-encesinskinproperties(e.g.betweenratandmouse,different partsofthebody)candeterminewhetherdeviceswillremain inthepocketscreatedforthem,orwhethertheyneedtethering, forexamplewithapermanentsuture.

䊏Intraperitoneal—Somedevicesaretoobigtomount subcuta-neouslyandareimplantedinsidetheabdomen.Careisneeded onthelocationsofdevicesandthepathsofwirestothe recor-dingsitestoavoidrestrictingnaturalmovementsandtoavoid mechanicaldamagetoadjacenttissues.

䊏Harnesses—Somesystemsusespecies-specificharnessesor sad-dlestocarryexternalbatteriesoreventheentiredevice(Ewing etal.,2013).Theyshouldbeappropriatetotheage/size/speciesof theexperimentalanimalunderstudyandpermitfreemovement withfrequentchecksmadeforevidenceofrubbingor discom-fort.

Surgicalimplantationofelectrodes:Inalmostallcases elec-trophysiologicalrecordingrequirespreparatorysurgerytoimplant orattachelectrodes,connectors,telemeters,cannulaeandother devices.Electrodescanbeimplantedintobrainstructuresusing stereotaxicsurgery,orontothecorticalsurfaceusingeithera skull-screwelectrodeorawirecementedintoaburrhole.Largenumbers ofelectrodescanbeincorporatedintoultrathinandflexible elec-trode arrays (Wu et al., 2008; Viventi et al.,2010; Park et al., 2014).

Good surgical practice, with proper attention to antibiotic prophylaxis, full aseptic technique (see video tutorials on the NC3Rs-fundedProceduresWithCarewebsite4),painmanagement,

maintenance of body temperature, replenishment of fluidslost underanaesthesiaandeffectivepost-operativecarearerequired (seeSection3.4)(Fornarietal.,2012).Insomecasessurgerycan beextensive,requiringcarefulplanningandexecutionofboththe operationandsubsequentpost-operativecare.

Whatever the electrode assembly, it needs to be securely anchoredinplace.Lossoftheheadstagewasreportedinthesurvey

asadefinedhumaneendpoint(seeSection3.5).Typicallyelectrodes willbefixedtotheskullusingcement(e.g.dentalacrylicorglass ionomer)andanchoringskullscrews.Insomecasesskullscrews arenotfeasible(e.g.inthethinskullsofneonatalrats),inwhich case,carefulmatchingoftheshapeofthedevicetotheslight cur-vatureoftheskullallowstheuseofcyanoacrylategluestoanchor radiotelemetrydevices(Zayachkivskyetal.,2013).

Animalswith head-mounteddevices may requireadditional housingspaceanditmaybeprudenttoblockaccesstolowfood hoppers,ortoavoidwirelidswithgapsthatcantrapprojections fromthehead-mount.Choicesofhousingshouldalsoconsiderthe risk ofdamagetohead-mounteditems(see Section3.8 Enrich-ment).Thelatestindividuallyventilatedcage(IVC)systemsinclude double height cages from which the shelf can be removed to minimisetheriskofheadimplantsbeingcaughtin thecageor lid.

Recommendations:

8.The experimental setup should be maximally effective in delivering the research objectives while prioritising animal welfare and minimising interference withbehaviour, espe-cially in behavioural studieswhere the instrumentationfor seizure recording may impede movement and significantly alterbehaviour(GradeD).

9.Wherever possible,radiotelemetry should be used in pref-erence totethered systems for chronicelectrophysiological recordings(GradeD).

10.Radiotelemetry devices shouldbe aslight aspossible, con-sistentwiththescientificobjectives.Considerationshouldbe giventothephysiologicalconformationofthedeviceandits potentialimpactonpostureandnaturalbehaviours(e.g. eat-ing,drinking,groomingandrearing)(GradeC;Mortonetal., 2003;Hawkinsetal.,2004,LevelIII).

11.Goodsurgicalpracticeandaseptictechniqueshouldbeused, with pain management, maintenance of body temperature, replenishmentof fluidslostunderanaesthesiaandeffective post-operativecareandconsiderationofantibioticprophylaxis (GradeD)(seerecommendation15).

3.4. Perioperativecare

Severalmodelsofepilepsyrequiresurgicalprocedurestobe undertakenforintracranialelectrodeimplantationandstimulation (seeSection3.3)and/orstereotaxicinjectionofseizure-inducing compounds(Bouilleretetal.,1999;LévesqueandAvoli,2013).The careprovidedbefore,duringandaftersurgicalprocedures (peri-operativecare)iscriticalforminimisingpainanddiscomfort,and improvingstudyoutcomes.

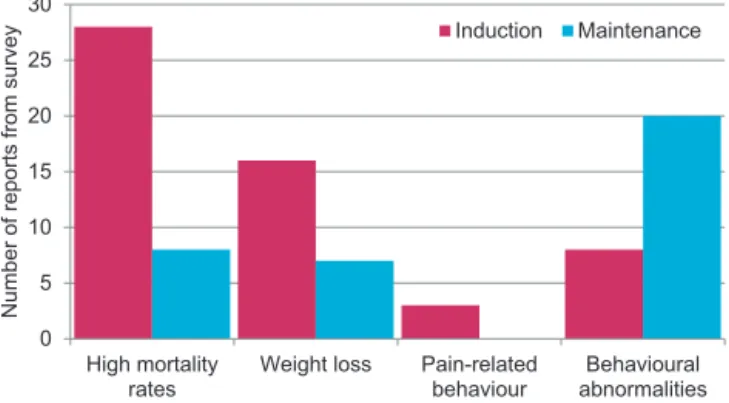

Tounderstandcurrentpractices,evidencewasgatheredfrom thesurveyandliteraturesearch.Thesurveyaskedresearchershow theyavoidandminimiseadverseeffects(Fig.4).Themostcommon

Group housing Refine welfare monitoring protocol Administer peripheral antagonist Additional warmth Extra nesting material Provide analgesia Minimise duration of study Limit intensity of seizures Single housing Modify food source

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

Number of reports from survey

Fig.4.Refinementofadverseeffectsduringinductionand/ormaintenanceof exper-imentalepilepsy.Stepstakentocontrolandrefineadverseeffectsinresponsetothe question:“Howdoyoucontrolandrefineadverseeffects?”.

controlmeasurewasmodificationofthefoodsourceprovidedto animalstoencourageeatingandpreventweightloss,for exam-plesoftenedstandardfoodpellets,gelsandtreats,whichareoften placedonthecagefloor.Inadditiontomodificationsdetailedin Fig.4,researchersalsoreportedadministrationofsubcutaneous fluidsfollowingsurgery,applicationoftopicalandsystemic antibi-oticstopreventinfection,extracarewhenhandlingseizure-prone animals,and theuseof skilledand knowledgeableanimal care staff,withgoodcommunicationbetweenthem,veterinarians,and researchers.

Animalsshouldbegiventimetorecoverfromsurgerybefore astudycommences andprovided withnecessaryresources,for example,heatingblanketoratemperature-controlledwarm cab-inet(avoidtheuseofheatlamps)topreventhypothermiauntil thereisevidenceofrecovery(McIntyre,2005;ZhaoandHolmes, 2005;GraberandPrince,2005).

Analgesiaandanaesthetics:Question5aofthesurveyasked researchers:“Whatadverse effectsdo you observeatinduction and/or during maintenance of experimental epilepsy?” Pain-related behaviour was reported in 3/44 (7%) of responses and allsuchcaseswereassociatedwithchemically-inducedepilepsy duringthe induction process. No pain-relatedbehaviours were reportedtobeobservedduringmaintenanceofepilepticanimals. Useofanalgesiawasreportedin18/51(35%)responsestoquestion 5b“Howdoyoucontrolandrefineadverseeffects?”;howeverthis mayreflectunder-reportingofstandardpractice.

Pain during seizures is a rare phenomenon in people with epilepsy(Young and Blume, 1983)and it is thought tohave a similarlylowincidenceinanimalmodelsofseizures.Postictal noci-ceptivethresholdshavebeenassessedinexperimentally-induced epilepticseizuresinanimalsusingthermalnociceptivetests(tail flick,plantar,hotplate)showingapostictalanti-nociceptiveeffect observed for 30–120min after seizures (Caldecott-Hazard and Liebeskind,1982; Caldecott-Hazardet al., 1982;Coimbraet al., 2001;Freitasetal.,2005;MareˇsandRokyta,2009).Longer-term anti-nociceptiveeffectshavenotbeendefined.Althoughitappears painassociatedwithseizuresisminimalandinfrequent,thereis,as forallsurgicalprocedures,thepotentialforanimalstoexperience pain.Protocolsforidentifyingandalleviatingpainaroundthistime arethereforerequired.

Toestimatecurrentpracticeinanalgesicadministrationin ani-malmodelsofepilepsyundergoingsurgicalprocedures,asmall literaturereviewwascarriedout.Peer-reviewedscientificpapers reportingkainic acid-inducedseizurespublishedbetween2012 and2014wereincludedintheanalysis.Atotalof20paperswere screenedforinclusioneligibility(i.e.ifthepaperdescribedsurgical procedures);eightpaperswereexcludedbecausenosurgical pro-cedureswereinvolved.Ofthe12papersincludedintheanalysis (GuoandKuang,1993;Inostrozaetal.,2012;Bernardetal.,2013; Chungetal.,2013;Xuetal.,2013;Dugladzeetal.,2013;Harhausen etal.,2013;HuangandvanLuijtelaar,2013;Jimenez-Pachecoetal., 2013;Lietal.,2013;Qiaoetal.,2013;Simeoneetal.,2014),11/12 (92%)reportedtheuseofanaesthetics,butonly3/12(25%)reported theuseofanalgesics.Thelowlevelofreportingofanalgesiais con-sistentwithpreviousreportsinrodentsundergoingexperimental surgicalprocedures(RichardsonandFlecknell,2005;Stokesetal., 2009));howeverthismayreflectunder-reporting.UntiltheARRIVE guidelines5areroutinelyandfullyimplementedwhenreporting

animalstudies,itwillremaindifficulttoascertainwhetherpainis beingmanagedappropriately.

5 LedbytheNC3Rs,theARRIVEguidelines(www.nc3rs.org.uk/ARRIVE)were

developedtoimprovethereportingofanimalresearch,maximisetheinformation publishedandminimiseunnecessaryanimaluse.(Kilkennyetal.,2010).

Anaesthesiaandanalgesiashouldbeusedtoalleviatepain asso-ciatedwith invasiveprocedures suchas stereotaxic deliveryof convulsantsandelectrodeimplantation.Inothersurgicalcontexts analgesia has beenshown toaid recovery (Hayes et al., 2000; Shavitetal.,2005).Theanaestheticandanalgesicformulation,dose androuteofadministrationshouldfollowadvicefromthe veteri-narian,andshouldbereportedinpublishedpapers.Anaesthetic agentsshouldbechosencarefullyduetotheirpotentialeffectson thephysiologyoftheanimal(Tremoledaetal.,2012).For exam-ple,pilocarpine-inducedSEratsshowanenhanced responseto generalanaesthesia(pentobarbital,halothaneandpropofol), pro-longedlossoftail-pinchresponseand lossofrightingreflex.In contrast,theamygdalakindlingmodeldoesnotshowenhanced responsetogeneralanaesthesia(Longetal.,2009).

Thereare indications that certainanalgesic drugs (e.g. neu-rolepticsandopioids)haveaneffectonseizuresusceptibilityand expression(Czuczwarand Frey,1986; HashemandFrey,1988). Pharmacokineticandpharmacodynamicfactorsneedtobe con-sidered withco-administration of drugs.If thisis a problemin thespecificmodelbeingproduced,thenalternativeagentssuchas NSAIDs(seeGlossary)combinedwithlocalanaestheticblockusing acombinationoflidocaineandbupivacainecanbeconsidered.Care mustbetakenwithlocalanaestheticsasleakageontothecortexcan causeseizures.Theuseofanalgesicsmayberequiredunder legisla-tioninsomecountriesunlessthereisrobustscientificjustification. Withholdingofanalgesiafollowinganinvasiveproceduremustbe justifiedtotheAWERB/IACUC(seeGlossary).

TheMouseGrimaceScale(Langfordetal.,2010;Leachetal., 2012)andRatGrimaceScale(Sotocinaletal.,2011;Oliveretal., 2014)havebeenshowntoberapid,reliableandeffectivemethods forassessingpost-operativepain.Anadditionalquestionaboutuse ofgrimacescales“DoyouusetheMouseGrimaceScale(MGS)orthe RatGrimaceScale(RGS)toassesspain?”wasaddedtothesurvey. Onlyfourrespondents(13%)usedthegrimacescalestoassesspain inmiceandrats.

Infection:Inflammation due to infection can interfere with seizure susceptibilityand infections have beenshown tocause higher seizure susceptibility in audiogenic and electroshock-induced seizures (Flandera et al., 1973). Prenatal immune challengescanalsocauseanincreaseinseizuresusceptibility(Yin etal.,2013).Inthesurvey,onlytwosurveyrespondentsreported post-operativeinfection;oneasacriterionforthehumane end-point and the other as a complication of surgery, which was avoidedbyusingtopicalantibioticapplication.Infectionsshouldbe avoidedbyusingbestpractices,includingaseptictechnique dur-ingsurgicalprocedures.However,maintainingstrictasepsisduring compleximplantprocedurescanbechallenging,andasanadjunct tothis,prophylacticantibiotictreatmentshouldbegivenif appro-priateontheadviceoftheveterinarian.Thechoiceofantibiotics requirescarefulconsideration;evidencesuggeststhe tetracycline-classantibiotics (e.g.minocycline,doxycyclineand tetracycline) haveanti-apoptoticandanti-inflammatoryeffects(Abrahametal., 2012;Wangetal.,2012).

Foodandfluids: Followinginduction,thefeedingbehaviour ofanimalsmaybecomedisrupted.Forexample,animalsinjected withtetanustoxindisplayintermittentattacksof‘paroxysmal eat-ing’lastinga minuteortwo,whereanimalsconsumetheirfood pelletswithexcessivevigour(Mellanbyetal.,1999).Modification offoodsourcewasthemostfrequentlyreportedmethodto min-imiseadverseeffects(weightloss)mentionedinthesurvey.Several studieshave reported usingmodified food,including enhanced dietaryglucosetoaccelerateweightgainfollowingSE(Jedrzejko andPersinger,2001).Hand-feedinganimalswithfruitjuicesmixed withsweetenedmilkormashed foodpelletscanalsobe bene-ficialforanimalsinapoorconditionfollowingseizureinduction (McIntyre;Persingeretal.,1988).

Recommendations:

12.Animalsshouldbeallowedsufficienttimetorecover follow-ingsurgicalproceduresusinganaesthesia,beforesubsequent recordings/measurements are taken (GradeA; Culleyet al., 2004,LevelI+).

13.Stepsshouldbetakentoidentify,assessandalleviatepain fol-lowingproceduresrequiringsurgery.Appropriatepainrelief shouldbeprovidedandreportedinpublications.Choiceof anal-gesicshouldbemadewithcarebasedonveterinaryadviceand takingintoaccountevidenceofpotentialinterferencewiththe science(GradeC;Tremoledaetal.,2012,LevelIII).

14.Topical antibiotics should be used for simple surgical pro-cedures and prophylactic antibiotics used for implantation proceduresifappropriate,basedonveterinaryadvice(Grade D).

15.Amodifiedfoodsourceshouldbeprovidedtoencourage eat-ingandpreventweightlossfollowingsurgeryand/orseizure induction(GradeA;JedrzejkoandPersinger,2001,LevelI).This shouldbeintroducedpriortosurgerytoensurefamiliarisation andconsumption.Foodanddrinkshouldbeaccessiblefromthe floorofthecage(GradeD).

3.5. Welfareassessment

The creationof chronic diseaseconditions, including rodent modelsofepilepsy,requirescontinuouswelfareassessment.The severityandfrequency oftheadverse effects willdependupon themodelofepilepsy.Geneticmodelsmayshowearlyfailureto thriveandexcessneonatalandjuvenilemortality.Othermodels ofepileptogenesisinpreviouslynormalanimalsmayalsopresent welfareissuesuniquetotheinductionmethod(e.g.electrical stim-ulationorchemicaltreatments).Oncetheepilepticstatehasbeen produced,on-goingadverseeffectsrelatedtotheseizureactivity mustbetakenintoaccount.Inadditiontoprovidinganimmediate assessmentoftheanimal’sstateofhealthandwelfare,the infor-mationgainedfromwelfareassessmentsenablescompliancewith thelegalrequirementsinmanycountriesforprospectiveseverity classificationoftheexperimentalproceduresandsubsequent ret-rospectiveassessmentofseverityexperiencedbytheanimals(see AnnexVIIIofDirective2010/63/EU).Theseverityclassificationcan beassignedaccordingtoclinicalsignsobservedduringthe assess-ment(Baumansetal.,1994).Thiscanthenbeusedtodeterminethe appropriateactionregardingthecontinuationofastudywithdue allowanceforsafeguardinganimalwelfare.Theassessmentshould, wheneverpossible,usedatafromadverseeffectsobservedinthe animalmodel,ratherthanbysimpleextrapolationfromman.

The survey showed adverse effects observed at induction includehighmortality,weightlossand,insomecases,pain-related behaviour. During the maintenance phase themost commonly reportedadverseeffectswerebehaviouralabnormalities,suchas aggressionandhyper-reactivity(Fig.5).Managementof aggres-sioncanresultinanimalsbeingsingly-housed,furtherimpacting ontheirwelfare(seeSection3.7Socialhousing).Evidencefrom the literature search shows that the number of seizures and seizure-inducedneuronaldamageiscorrelatedwiththeseverityof aggressioninanimalmodelsofepilepsy(DesjardinsandPersinger, 1995;Persinger,1996;Huangetal.,2012).Somemethodstoinduce seizures,suchaskindling, canresult inlong-lastingchanges in emotionalbehaviour(FrankeandKittner,2001),whichhavebeen showntobedefensiveinnature(Kalynchuketal.,1999).However, somecomorbiditiesassociatedwithclinicalepilepsy(e.g. aggres-sion)areanintegralpartofthediseaseandmaybetheobjectof theresearch.

Animalwelfareassessmentsmustbeconductedtoassessthe stateofwellbeing and healthof each individualanimal. Where

High mortality rates

Weight loss Pain-related behaviour Behavioural abnormalities 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Number of reports from survey Induction Maintenance

Fig.5.Adverseeffectsduringinductionandmaintenanceinresponsetothe ques-tion:“Whatadverseeffectsdoyouobserveatinductionand/orduringmaintenance oftheexperimentalepilepsy?”.

experimentalproceduresunavoidablyimpactonthehealthofthe animal,whichincludesmanydiseasemodels,appropriatewelfare assessmentswillenabletheimpactoftheprocedurestobe recog-nisedandactiontakentominimiseharmbyintervention/treatment andtheapplicationofhumaneendpoints(seeSection3.7).

Effectiveandregularmonitoringofwelfareisbestfacilitated bytheuseofscoresheets(Jonesetal.,1999;Morton,1999,2000; Hawkins,2014).Thesurveyshowed21respondents(38%ofthe total)reportedusingascoringsystem.Usingaformalisedscoring systemhastheadvantageofencouragingasystematic,structured examinationoftheanimal,andhelpsensureaconsistentevaluation atdifferenttimepoints,andbydifferentassessors.Scoressheets alsoprovideausefulbasisforcommunicationbetweenresearchers andanimalcarestaff.Howtobesttailorthemostappropriate sco-ringsystemforeachestablishment,species,projectandgroupof personnelhasbeenreviewedindetailbyHawkinsetal.(2011).

Examinationoftheanimal’sphysicalappearanceandbehaviour isessentialfortheconductofwelfareassessment.Routine obser-vationsshouldbeperformedonadailybasis,andthisisalegal requirementundersomejurisdictions,althoughspecificreportsare typicallyonlymadeifthereisconcernoverthehealthofthe ani-mal.Amoredetailed welfareassessmentscoringsystemshould beconsidered,particularlyifnewmodelsarebeingintroduced, or ifa particularmodelis knowntopresent significant comor-bidities.Criteriausedforscoringsystemsthatweredescribedby respondentsin thesurvey includedbody weight,furcondition, piloerection,colourofskin,aggressivebehaviour,social interac-tions, ocularkeratitis, ataxia,tremor, ptosis,straubtail, righting reflex,mydriasis, catalepsy and mortalityrate (see Glossary).In addition,Table4providesalistofgeneralwelfareassessment crite-riaforlaboratoryrodents.Assessmentsshouldbemadebothby observationoftheanimal in anundisturbedstate,and thenby moredetailedinspectioninvolving,ifnecessary,removalfromits cage.Careisneeded,however,wherehandlingmayprovoke hyper-reactivityandcompromise,ratherthanpromoteanimalwell-being. Duetothespecificnatureof animalmodels ofepilepsyand theirassociatedadverseeffects,anumberofscoringsystemshave beendevelopedtocapturetheseizuretypeobserved.TheRacine Scale(Racine,1972)wasoriginallydevelopedtoclassifyseizures inducedbyelectricalstimulationtothehippocampusoramygdala inrodents.ThemodifiedRacinescalewasintroducedforPTZ chem-icalinduction(Lüttjohannetal.,2009)anddescribesawiderrange ofmotorseizures,possiblyduetotheconvulsantreachingmore partsofthebrainthanthefocalstimulationofamygdalakindling. Itisimportanttorealisethatthesescalesarenotnecessarily gener-alisabletootherseizuremodelsandimmatureanimals.Proposals havebeenmadetoquantifyanimalsufferingbasedonseizure sco-ring(Wolfensohnetal.,2013)buttheWorkingGroupconsiders

Table4

Welfareassessmentcriteria.Examinationofananimal’sphysicalappearanceandbehaviourisessentialfortheconductofthewelfareassessment.Table adaptedfromAHWLA(AssessingtheHealthandWelfareofLaboratoryAnimals)www.ahwla.org.ukandbaseduponexperiencefromtheWorkingGroup. Positivewelfareindicators(grey)andnegativewelfareindicators(white)arecategorisedintothreedistinctareas:thecageenvironment,animalbehaviour andthephysicalappearanceoftheanimal.

Category Indicators

The cage

environment

Evidence of eating and drinking

Evidence of fresh faeces and urine

Evidence of nest building and use / a good quality nest (mice)

Any blood staining of the cage sides or bedding

Animal

behaviour

Alert to external stimuli

Interested in surroundings (e.g. use of enrichment items)

Normal interactions with handlers (e.g. not overly aggressive or overly passive)

Normal interactions with other animals (e.g. no increase in aggression or anxiety behaviour, such marked escape

responses or hiding)

Isolated or withdrawn from other animals in the social group

Abnormal posture (e.g. hunched posture, tilted head)

Abnormal movements (e.g. abnormal gait, uncoordinated movement, lack of movement in the cage or on the bench)

Physical

appearance

of the animal

Good body condition (i.e. not overconditioned or underconditioned as defined in Ullman-Culleré & Foltz 1999

Appropriate body weight (i.e. within normal range for age-matched controls; no significant weight loss or increase)

Mucous membranes pink and moist

Eyes clear and bright; free from discharge or prophyrin staining (rat) indicative of stress or disease; not sunken, dull or

closed/semi-closed

Nose free from discharge

Mouth (including teeth and tongue) free from injury or abnormalities (e.g. malocclusion/overgrown teeth, salivation)

Tail and anal genital area free from injury and discharge/soiling

Normal skin and limbs (e.g. free from physical injury, lack of skin tenting = dehydration)

Poor coat condition (e.g. unkempt due to lack of grooming, greasy, faecal or urine stained, piloerection, hair loss)

Abnormal facial expressions, indicative of pain (e.g. grimace score of 1 or 2 using the rat (Sotocinal et al. 2011)and

mouse (Langford et al. 2010)grimace scales

thistobeoflimitedvalueduetopoorassociationofseizurescore

withanimalsuffering.

Recommendations:

16.Eachanimalmodelofepilepsyshouldbeassessedandan

appro-priatewelfarescoresheetvalidatedbybothanimalcarestaff

andtheprincipalinvestigator.Thescoresheetshoulddefine

whenactionshouldbetakentominimisepain,sufferingand/or

distressbyintervention/treatmentandapplicationofhumane

endpoints.Suchscoringsystemsshouldincorporateboth

moni-toringofactualmodelinductionandmonitoringoftheresulting

epilepticstate(GradeD).

17.Animal welfare assessments shouldbe conducted at a

fre-quencyappropriatetothestateofwell-beingandhealthofthe

individualanimal;atleastonadailybasisandmultipletimes

perdayintheimmediatepost-operativerecoveryperiodor

followingspecificinterventions(GradeD).

3.6. Humaneendpoints

Humaneendpoints canbedefinedasasetofpredetermined

physiological and/or behavioural signs that define the point at

whichananimalwillberemovedfromanexperimentalstudy(e.g.

byhumanekilling)beforeitexperiencesunacceptableharmwhilst

stillmeetingtheexperimentalobjectives.Theimplementationof

humaneendpointsisamajormeansofrefinement(Morton,1999;

Hendriksenetal.,2011; Ashall,2014).Identificationofhumane endpointsneedstotakeintoaccountclinicalaspectsofthe dis-easebeingmodelled,whicharguablycanbeharmfulwhilebeing legitimatesubjectsforstudy;insuchcases,careneedstobetaken tobalanceharmsandpotentialbenefits.

Clearlydefinedscientificobjectivesarepivotaltohelp deter-minetheearliestexperimentalandhumaneendpoints.Themost effectivebiologicalindicatorsthatdenotesuccessorfailureofan experimentandwhich precedeanyunjustifiablesufferingofan

animal,shouldbeobtainedpriortothestartoftheexperimentand reviewedregularlybyateamofanimalcarestaff,thescientistsand theveterinarian(Ashall,2014;Hawkins,2014).Successful imple-mentationofhumaneendpointsreliesontrainingandteamwork (Hau,1999;Hawkinsetal.,2011).Toensureanimalsufferingis kepttoanabsoluteminimum,thepredeterminedbiological indi-catorsofsufferingandpoorwelfareneedtobedetectedasquickly aspossibleandacteduponefficiently,forexamplebyproviding veterinarycaresuchaspainreliefor,ifnecessary,euthanasiaof theaffectedanimal.

Fewpublishedepilepsystudiesaddresstheissueofhumane endpoints(Lüttjohannetal.,2009).Thereforethesurveywasused toassesswhenand howhumane endpointsareusedin animal modelsofepilepsy.Humaneendpointswereusedby39/44(67%) respondentstoquestion6“Do youusea definedhumane end-point?”;withthemostcommonhumaneendpointcriteriabeing significantbodyweightloss(rangingfrom10%to25%weightloss frompre-inductionstarting weight),signsof distress(including porphyriastaining,poorgrooming,difficultybreathing),opening ofwoundsorlossofanimplant,woundinfection,andprolonged repetitiveseizures.Followingaveryprolongedseizure(SE)or post-operatively(pain),animalscanhavedifficultiesdrinkingoreating, whichcanresultinasignificantdecreaseinbodyweightdueto dehydrationorreducedfoodintake.

Theresultsof thesurvey reflect that thesinglemost objec-tiveclinicalsignischangeinbodyweight(VanVlissingenetal., 1999).Bodyweightiseasytomeasureandrecordbutisarelatively non-specificwelfareindicator.Bothanabnormalincrease anda substantialdecreaseinbodyweightcanbeassociatedwithserious distressandsuffering.Therateofchange,aswellastheabsolute change,canbeofimportance.

Inepilepsymodelssuddenincreasesin bodyweights canbe observed,associatedwithunrelatedillnessessuchasthe devel-opmentofneoplasmsandfluidretention. Seizurescanresultin bodyfluidlossandthiscanproduceshort-termchangesinweight.

Carefulmonitoringofbodyweightthereforeneedstobecarriedout regularly(seeSection3.5)anddietamendedasnecessary.Ifan ani-maldoesnoteatordrinknormallyandasaresulthasasignificant bodyweightloss,euthanasiashouldbeconsidered.

Bodyweightmeasurementsshouldnotonlybecomparedtothe previousmeasurements,butalsoplottedinachartandcompared tothenormalgrowthcurveforthatspeciesandstrain.Thiswill enableassessmentofwhethertheanimalsaregrowingnormally; conditionscoringcanalsobeusedforthispurpose(Ullman-Culleré andFoltz,1999;HickmanandSwan,2010).Forexample, reduc-tion in weightgain or an absoluteloss in body weight canbe usedtodetermineahumaneendpoint(Jonesetal.,1999).Useof weightasthesolecriterionforapplicationofahumaneendpoint isofteninappropriate(Chapmanetal.,2013);inadditiontobody weightloss,other“signsofdistress”shouldbeidentified,for exam-ple;appearance(coatcondition,postureandmobility/gait),clinical signs (respiration, salivation, tremors, prostration), unprovoked behaviour(socialisation, vocalisation)and response to stimulus (provokedbehaviour)(Jonesetal.,1999).

Definedendpointsneedtobetailoredspecificallytotheepilepsy modelused.Thetype,duration,intensityandfrequencyofseizures, recoverytimeandthelevelofsufferingfollowingtheinitiationof aseizure(ifnotspontaneousrecurrentseizures)consideredtobe acceptablewilldifferwitheachexperimentalmodelandneedsto bedefined.Forexample,ifSEcannotbestoppedby pharmaco-logicalinterventionwithinthedefinedtime,theanimalshouldbe euthanised.IfSEisnottheexpectedoutcomeofthemodel,itshould beavoidedandcontrolledifitoccursunexpectedly.

Recommendations:

18.Atailoredapproachshouldbeadoptedtoassess,defineand implementhumaneendpointsforeachexperimentinorderto minimiseharms,whilstallowingachievementofthescientific objectives(GradeC;Morton,1999,LevelIII).Thisshouldtake intoconsiderationthecurrentlegalframework,scientific, justi-fiableandunpredictedendpoints(seeGlossary)andtheresults ofwelfareassessments.

3.7. Socialhousing

Socialinteractions areimportant contributorstothewelfare of rodents,provided that thegroupcomposition is appropriate for the species, age, sex and strain. Social housing is the rec-ommended default housing configuration under legislation on protection of animals used in science (European Union, 2010; NationalResearchCouncil,2011;HomeOffice,2014).Individual housinghasbeenshowntobestressfulforrodents,givingriseto behaviouralandphysiologicalabnormalities (Hatchetal.,1963; Brain,1975;Hasemanetal.,1994;Hurstetal.,1997;Võikaretal., 2005;Meijeretal.,2006;Kalliokoskietal.,2014),and is there-forerecognisedasaharmandregulatedundersomejurisdictions. Housing ofsingle-sex groupsof male andfemale ratsdoesnot

usuallyposeproblems.Sociallyhousedmalemice,however,may showterritorialbehaviour,aggressionandfighting,dependingon strain,previousexperienceandcageenrichment(VanLooetal., 2001).Nonetheless,thereisevidencethatsubordinatemalemice prefercompanytobeinghousedindividually,eveniftheir compan-ionisdominant(VanLooetal.,2001).Provisionofvisualbarriers andrefugesthatallowanimalstowithdrawoutofsightwhena threatoccurscanreduceaggression.

Theissueofgrouporsinglehousingforrodentsusedinepilepsy studiesiscomplex.Whilstgrouphousingshouldbebestpractice, theremovalofindividualanimalsforsurgeryorbehavioural test-ingcanresultinthedisruptionofanestablishedsocialhierarchy (Ferrarietal.,1998;Bartolomuccietal.,2001,2004;Arndtetal., 2009),whilsttheappearanceofdisturbedbehaviour (aggressive-nessorpassivity)inexperimentalanimals(e.g.animalsdisplaying overtseizures(Mellanbyetal.,1981)orthatareinstrumented)may provokehostileresponsesfromcage-mates.Companionratshave beenseentobiteratsthatareexperiencingseizuresandmaycause injury,ortheymaybiteexposeddevicesincludinghead-mounted guidecannulae,electrophysiologicalconnectionsandtelemeters; ineitherofthesecases,theanimalsshouldbeseparated.Earlyafter majorsurgeryacompanionmayeatappealingfoodsfasterthanthe recoveringratanddelayrestorationofweight.Onrareoccasions apparentlyneutralbehaviouralcontactbetweenratshastriggered seizures,sothatremovingthecompanion maybebeneficialfor theepilepticrat.Thetendencyforepilepticratstobesubmissive mayaffectthesocialhierarchyingrouphousingwhichcouldcreate confoundsforsomekindsofexperiments(Castelhanoetal.,2013), particularlyforthoseinvestigatingbehaviouralcomorbidities.

Severalstudiessupportthehypothesisthatsocialhousing accel-eratespost-surgicalrecoveryinrodentdiseasemodels(Baranetal., 2010;Jirkof,2015).Thesurveyaskedhowanimalswerehoused duringanexperiment(afterinduction)andtheresultsshowedthat instrumentedanimalsweremorelikelytobesinglyhoused(36/49, 73%oftotal)comparedtonon-instrumentedanimals(16/49,33%of total)(Fig.6).Rodentsareoftenhousedindividuallyaftersurgical proceduresbecausetheymaydisturbeachother’sincisions,butthis isarareoccurrenceandmaybeaddressedbyuseofsubcuticular sutures.TheexperienceofsomemembersoftheWorkingGroup isthatafamiliarcompanionanimalhelpsacceleraterecoveryof animalsthathaveundergoneprolongedand/orcomplexsurgery, butthatthecompanionanimalmayneedtoberemovediffighting occurs.Grouphousingneedscarefulmonitoring,ideallywithvideo recording,todetectadverseeffectsthatmaybedetrimentaltothe welfareoftheepilepticanimalortothereliabilityofthe experi-mentalresults.Thepossibilityexiststodividecageswithagrid-like barrierthatallowsodoursandsomephysicalcontactwhilst reduc-ingtheriskofseriousinjuryandallowingretreattosafety(VanLoo etal.,2007;Boggianoetal.,2008).Whilstthisseemslikeasuitable compromise,spaceissuesariseiflargerrodentssuchasratsare confinedtoonehalfofastandardcage(Boggianoetal.,2008)and increasedlevelsofstresswerereportedinmiceseparatedbyagrid

Non-instrumented Instrumented

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

% of reports from survey

Singly housed Group/pair housed