Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia

Scuola di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica Direttore: Prof. Alfredo Falcone

Hypertension:

prognostic and predictive factor in

metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)?

Specializzando: Relatore:

Dott. Lisa Derosa Prof. Alfredo Falcone

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

ABSTRACT

Purpose

Hypertension (HTN), one of the most frequent side effects of VEGF inhibitors, has been related with outcome in mRCC. We aimed to investigate the association between HTN, Angiotensin System Inhibitors (ASI) use and survival outcomes in patients (pts) with mRCC treated with sunitinib (SU).

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 213 pts with mRCC who received SU as first line treatment from April 2004 to November 2013. Baseline HTN (diagnosis and treatment before SU), use of ASI (either before or during SU) were analysed, and outcome (PFS, OS and response rate) of the different subgroups were compared. Survivals were compared with log-rank test and hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) through a multivariable Cox model adjusted on important covariables.

Results

134 (63%) pts were hypertensive divided into 88 (41%) HTN_PRE, and 46 (22%) HTN_POST (SU related HTN), respectively. Hypertensive pts have longer OS (median: 3.5 vs 1.4 years, p<0.0001) and better PFS (median: 1.1 vs 0.5 years, p<0.0001) than non hypertensive pts (n=79). Among hypertensive pts, ASI users (n=102) have longer OS (median: 3.7 vs 2.3 years, p=0.007) and longer PFS (median: 1.2 vs 0.7 years, p=0.03) than no ASI users (n=32). 88 (41%) HTN_PRE pts tended to have longer OS (median: 2.7 vs 1.9 years, p=0.003) and longer PFS (median: 1.0 vs 0.7 years, p=0.002) than 125 pts (59%) non-HTN_PRE. Pts who used ASI (n=105) had more HTN_PRE compared to those (n=108) who did not (65 vs 19%, p<0.001). After adjustment for age, gender, histology, IMDC prognostic group and HTN, ASI intake was associated with a significantly better OS ([HR], 0.40; 95% CI, 0.24-0.66, p=0.0004) and PFS ([HR], 0.55; 95% CI, 0.35-0.86, p=0.009). Total hypertensive was marginally associated with the two outcomes (p=0.05). Among ASI users, OS (HRprior/post=0.80 [0.41-1.57], p=0.51) and PFS (HR=0.84 [0.52-1.34], p=0.46) were not significantly different between ASI users before SU and ASI users during SU.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated that HTN is an independent prognostic factor of outcome in mRCC pts receiving SU. In addition, concomitant use of ASI (before or during SU) may significantly improve OS and PFS in these patients. There is no difference on outcome between pts who receive ASI before starting SU and those who received ASI during SU treatment.

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION

Page 04

1.1 Renal cancer

Page 04

1.2 Incidence, risk factors

Page 04

1.3 Clinical manifestation

Page 05

1.4 Primary tumour treatment

Page 05

1.5 Metastatic tumour

Page 06

1.6 Prognostic factors in mRCC

Page 07

1.7 Systemic treatments

Page 08

1.8 Predictive factors

Page 10

2. AIM OF THE STUDY

Page 11

3. PATIENTS AND METHODS

Page 12

4. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Page 13

5. RESULTS

Page 14

5.1 Patients Characteristics

Page 14

5.2 Impact of ASI use

Page 16

5.3 Impact of HTN

Page 20

6. CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

Page 25

7. REFERENCES

Page 28

8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Page 35

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

1.

INTRODUCTION

Real cancer claims 102,000 deaths per year worldwide1 and is notorious for its high metastatic

frequency and high resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy2-3.

Hence, patients with metastatic renal cancer have a truly poor prognosis. The lack of curative treatment results in a median survival of only 10 months4. Hypertension (HTN) has been shown to be one of the risk factors for RCC and indicator of best response at treatment in mRCC and defined as predictive factor. This thesis describes for the first time HTN as prognostic factor and the association between Angiotensin System Inhibitors (ASI) use and survival outcomes in patients (pts) with mRCC treated with sunitinib (SU). In the introduction section, various aspects of renal cancer, as well as prognostic and predictive factors will be covered in some detail.

1.1 Renal cancer

With an incidence of about 5 % of all solid tumors, cancer of the kidney is not as common as breast or prostate cancer. However, it still claims 107,000 lives every year out of the 209,000 new cases diagnosed worldwide5. The most common form of renal cancer is the conventional (clear cell) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). It constitutes 75% of all renal carcinomas. The remainder is distributed between papillary renal carcinoma (10-15%), chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (5%), collective duct carcinoma (1%) and unclassified renal carcinoma (3-5%), according to the Heidelberg classification from 19966. Some other rare histologies include translocation RCC: this rare entity, mainly observed

in children or young adults is characterised by the translocation of Xp11.2, with the gene-fusion TFE3, or less frequently the translocation t(6;11)(p21;q12) and fusion TFEB7. Sarcomatoid

appearance may be present in all of the subtypes of renal cancer, and is a hallmark for high transformation. Furthermore, it is associated with a worse prognosis8. The absolute majority of renal

cancers are formed from cells in the tubular system in the kidney. Wilms’ tumor is an exception, since it seems to originate from the glomerular podocyte that express the same Wilms’ tumor (WT) antigen.

1.2 Incidence, risk factors

The global distribution of renal cancer varies, with the highest incidence in Europe, North America and Australia. In contrast, incidence is rising in the United States9. In general, there is a male predominance of 2:1. Smoking is an established, dose-dependent risk factor for renal cell carcinoma (RCC)10-16. Obesity and hypertension have also been shown to be risk factors for RCC, while fruits and vegetables are believed to have a protective effect. The average age at diagnosis and surgery is 61 years17.

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Overall survival varies with tumor status at diagnosis. Patients with local tumors at diagnosis, status T1 or T2 (please see Appendix for tumor staging), have a 5-year survival of over 80%. Furthermore, the prognosis and survival also vary with specific subtypes of RCC, with a worse prognosis for CCRCC compared to papillary RCC for T1 and T2 tumors. If the cancer has metastasized, the prognosis is significantly impaired18-20.

1.3 Clinical manifestation

Renal carcinoma is generally asymptomatic and the disease is typically discovered incidentally. The most common clinical manifestation is macroscopic hematuria, which is present in approximately 40% of the patients21. Previously, a classic triad of symptoms was expected by the clinicians namely hematuria, flank pain and a palpable tumor. However, these three symptoms combined occur only in a minority of the patients, less than 10%, and usually at an advanced state of the disease22. With the evolution of sophisticated detection techniques (e.g. computed tomography), tumor discovery has improved during the last decades23. This leads to tumors being detected at an earlier stage, and concomitantly less than 1% of cases are currently diagnosed by the classic triad24. The symptoms of renal carcinoma differ notably between patients and are often diffuse. Renal cancer, including renal cell carcinoma, is classified according to the TNM staging system. This system serves as a guide for treatment as well as for the prediction of patient outcome. Please refer to Appendix for details of the classification.

1.4 Primary tumour treatment

The sole curative treatment of renal cell carcinoma available today, is surgical removal of the entire tumor mass if it is localized to the kidney. This can be achieved either by radical nephrectomy (RN), i.e. removal of the entire kidney, or by open partial nephrectomy (OPN). OPN has been shown to be equally good in terms of overall survival for renal cancers for tumors fully localized to the kidney and smaller than 4 cm. There is also increasing evidence that partial nephrectomy outcomes for tumours that are 4-7 cm are similar to those smaller tumors, although available studies are retrospective and may be biased towards the selection of more complicated tumors for radical nephrectomy. Thus OPN is generally recommended for tumor no larger than 4 cm (T1a), but can be extended to tumors of 4-7 cm (T1b)25-26.

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

1.5 Metastatic tumour

The prognosis for patients with metastasis at diagnosis is significantly reduced; the 5-year survival is less than 10%27-28. Approximately 30% of the patients have an advanced disease at diagnosis and

furthermore one third with localized tumor initially will subsequently develop metastases29. The most common metastatic site is the lungs, followed by bone, lymph node, liver, adrenal gland and brain30. In contrast to the management of other solid tumours, removal of the primary tumour is often performed for patients with mRCC and in less than 1%, metastases (lung metastases most frequently) have gone through spontaneous remission, typically after the excision of the primary tumor31.Two prospective randomized trials have shown an improvement of median survival time in patients with metastatic disease submitted to cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN), (i.e. removal of the primary tumor), followed by interferon-α (IFN-α) treatment, compared to patients receiving IFN-α treatment alone. In the studies, the median survival in the surgery plus IFN group was 17.4 versus 11.7 months and 17 versus 7 months, respectively32-33.

In combination, these trials showed an improvement of median survival of 13.6 over 7.8 months, which was statistically significant34. However, it remains unclear if this benefit associated with CN continues in the era of targeted therapy. There are retrospective data in patients with mRCC that suggests CN may improve survival (19.8 vs. 9.4 months, p < 0.0001). Importantly, in this study the benefit was absent in the group with poor-prognostic risk as determined by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center risk model35. Further retrospective data showed than CN was of most benefit

in those patients where primary renal tumor accounts for the vast majority of the volume of the disease36.

Recent data from the International Metastatatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) suggest that cytoreductive nephrectomy improve survival: 20.6 vs 9.5 months (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.60 [0.52–0.69], P < .0001) and the multifactorial analysis adjusted for IMDC criteria found an incremental benefit of cytoreductive nephrectomy as survival lengthened, but not much benefit with shorter life expectancy. IMDC criteria build on Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center criteria and include Karnofsky performance status < 80%, time from diagnosis < 1 year, and results of four lab tests for anemia, hypercalcemia, neutrophilia, and thrombocytosis. The study enrolled insufficient numbers of patients to compare cytoreductive nephrectomy vs no nephrectomy in patients who had all six prognostic factors, but a significant survival benefit was detected in those with 0 to 3 prognostic factors. Together these retrospective data suggest that nephrectomy might have a role, especially in select individuals37.

A multinational, prospective, randomized trial is underway to answer this question (CARMENA: NCT00930033). Patients with untreated metastatic clear-cell RCC and a good performance status

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

(ECOG PS 0 or 1), are randomly assigned to either nephrectomy followed by sunitinib or to sunitinib alone. The primary endpoint of this non inferiority trial is overall survival, and the trial will include more than 1,000 patients. Patients in the systemic therapy-only arm can have palliative nephrectomy later in the disease process if deemed necessary for symptomatic control. There is a second randomized phase III study that compares immediate with deferred cytoreductive nephrectomy in mRCC (SURTIME: EORTC 30073). Patients in the study arm receive three complete cycles of sunitinib prior to planned nephrectomy. The primary endpoint is progression-free survival. In addition, sequential tissue and serum will be collected to identify genetic- and protein-profiles predictive of response and resistance. Together CARMENA and SURTIME complement one another, and both will address the role of cytoreductive nephrectomy in the targeted therapy era.

In addition, selected patients with solitary or oligometastatic disease are candidates for surgical metastasectomy. Most patients who undergo resection of a solitary metastasis experience recurrence, but long-term PFS has been reported. In a retrospective analysis of 887 patients treated with radical nephrectomy, estimated OS rates at 1, 5 and 10 years following the first occurrence of metastases were 82%, 45% and 31%, respectively for patients who received surgical treatment for all metastases. Significantly poorer estimated OS was observed for patients whose metastases were not surgically resected (51%, 8% and 2%; p<0.001)38.

1.6 Prognostic factors in mRCC

In advanced RCC, classic anatomical and histological features of the primary tumour have traditionally had limited predictive value39. The prognostic factors that have been identified in

metastasized disease are performance status, number and locations of metastatic sites, time to appearance of metastases, prior nephrectomy and curative surgical resection of metastases40. Bone

metastases have been traditionally regarded as a marker of shorter survival. However, it has been shown that the number of metastatic sites is a more important prognostic marker than the location41.

The baseline tumor burden is able to predict prognosis independently to localization of metastases42.

Some laboratory findings such as low hemoglobin and elevated lactate dehydrogenase, corrected serum calcium and inflammatory markers have been correlated with patient survival. In order to improve predictive accuracy and categorize patients into different risk groups, several algorithms have been developed by combining previously known prognostic factors. In the cytokine era, the most widely used prognostic tools for advanced RCC is the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) which combine clinical parameters including performance status, serum laboratory examinations, time from diagnosis to initiation of systemic therapy and also the number and location of metastatic sites in order to stratify patients into different risk categories43. A prognostic model

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

applicable to a patient treated with VEGF-target therapy has been recently developed, known as the International mRCC Database Consortium or Heng’s model. This model was derived from a retrospective study of 455 patients with mRCC treated with sunitinib, sorafenib or bevacizumab + IFN. Patients who received prior immunotherapy also were included. In this model, the role of low hemoglobin, high serum-corrected calcium, Karnofsky PS<80 and time from diagnosis to therapy initiation <1 year were confirmed as independent predictors of shorter survival. Furthermore the absolute neutrophil and platelet counts greater than the upper limit of normal were also considered prognostic factors. According to the number of prognostic factors, the OS was not reached in the favorable-risk group, but was 27.0 and 8.8 months in the intermediate risk and poor risk groups, respectively44.

1.7 Systemic treatments for advanced disease

Treatment approaches towards mRCC have changed considerably in recent years. Although cytokine therapy has been the main systemic treatment for mRCC for the past 20 years, recently developed targeted therapies are now overtaking this approach as a preferred option. These drugs, designed to target specific pathways involved in the pathogenesis of mRCC, have the potential to revolutionize mRCC treatment. They are discussed briefly below.In immunotherapy using cytokines, the object is to stimulate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and natural killer cells to react against the tumor cells. The two main candidates used as treatment for mRCC are interferon-α (IFN- α) and interleukin-2 (IL-2)45.

IFN-alpha was explored early as treatment in combination with vinblastine chemotherapy. The combination of IFN-alpha and vinblastine compared to vinblastine alone had a significant effect in median survival (67.6 versus 37.8 weeks)46. Subsequent studies, comparing IFN-alpha alone against

a combination of IFN-alpha and vinblastine showed no increased benefit for the combination; hence IFN-alpha was considered solely responsible for the survival benefit. A Cochrane review, from 2005, showed increased overall survival in IFN-alpha treated patients compared to control. The one-year mortality odds ratio (OR) was 0.56 [0.40, 0.77] for the pooled studies of 615 patients47. However, survival benefits were generally modest for IFN-alpha and recent randomized studies using HFN-alpha as a comparator have shown superiority for targeted therapies. Interleukin 2 (IL-2) was the first treatment approved by the food and drug administration (FDA) for treatment of mRCC. In a clinical trial with 255 patients, high dose IL-2 induced a complete responsein 5% of the patients and partial response in 9%. However, performance status was a predictive factor of the response to IL-2 and severe side effects were reported. In total, 4% of the patients died, likely due to the treatment,

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

reflecting a relatively high toxicity for high dose Il-248.Consequently, IL-2 monotherapy is now only

recommended for selected patients with mRCC who have clear-cell histology and a good risk profile. Since the detection of the von-Hippel Lindau (VHL) protein in clear cell renal cell carcinoma, therapies targeting the molecular pathways activated during VHL-deficiency have emerged. Mainly, these therapies affect neo-vascularization by inhibiting either vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or its receptor VEGF-receptor (VEGFR).

Sorafenib acts by inhibiting the VEGFR-2 and 3 and platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR). It also targets RAF signaling, thus inhibiting both angiogenesis together with proliferation49.

It has been shown to induce longer progression-free survival in IFN-alpha drop out patients, but has so far not been able to produce increased overall survival (OS). Sunitinib targets the VEGFR and PDGFR. In a clinical phase III trial, Sunitinib increased progression free survival compared to IFN-alpha with 6 months (11 vs. 5) and overall survival with 4.6 months (26.4 vs. 21.8)50. Both Sunitinib and Sorafenib have significant side effects, including hypertension, fatigue, and diarrhea51. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody, directed against soluble VEGF52. In a phase III trial,

combining bevacizumab with IFN-alpha versus IFN-alpha and placebo, a progression free survival benefit was observed in the bevacizumab arm (10.2 vs. 5.4 months). OS was not possible to assess. Known side effects of bevacizumab include proteinuria, bleeding and hypertension53. Axitinib is an

inhibitor of the VEGF-receptors54. In a phase III trial, axitinib was compared to sorafenib, as a second

line treatment. Results showed increased progression free survival in the axitinib arm (6.7 vs. 4.7 months). Side effects of axitinib are diarrhea, fatigue and hypertension55. Pazopanib blocks the

VEGRF, PDGFR and c-Kit56. A phase II trial of pazopanib versus placebo showed a tendency to increase in OS for pazopanib (22.9 vs. 20.5 months). This was not significant, though, probably due to crossover from the placebo arm to the treatment arm. Side effects reported where diarrhea, hypertension and liver abnormalities57.The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is participating in proliferation in cells by activating AKT/PI3 kinase pathway. By inhibiting mTOR, proliferation is impaired and it has been shown that blocking of mTOR activity also reduces the amount of HIF-α and VEGF58. Temsirolimus efficacy on renal cell carcinoma was assesses in untreated, poor risk patience, versus IFN-α and IFN-α and temsirolimus. Temsirolmus alone had the best OS with 10.9 months versus 7.3 months for IFN-α and 8.3 for IFN- α plus temsirolimus. In the combination group, both the IFN-α and the temsirolimus dose were lower than in the single treatment groups. Reported side effects for temsirolimus are rash, peripheral edema, hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia59. Everolimus versus placebo was evaluated in a phase III trial, as secondary treatment after progression post VEGRF treatment. PFS was 4.9 months for everolimus versus 1.9 months for placebo. Overall survival did not show any significant effect (14.8 vs. 14.4 months). This might be due to 80%

cross-Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

over of the patients from the placebo arm to the everolimus arm. Side effects reported were infection, dyspnea and fatigue60. Novel target are also being explored and a number of new targeted therapies

are entering clinical trials.

Cabozantinib targets tyrosine kinases including MET and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2. Cabozantinib has demonstrated clinical activity in multiple solid tumor types, including heavily pretreated subjects with mRCC61. A phase 3, open-label, multicenter study is ongoing and evaluates the efficacy and safety of cabozantinib compared with everolimus in subjects with mRCC (METEOR: NCT01865747).The primary endpoint is progression-free survival (PFS) as evaluated by an independent radiology review committee (IRC).

Nivolumab is an investigational antibody drug targeting programmed death-1 (PD-1), demonstrating activity in multiple cancer types. A phase 1 study of the fully human programmed death-1 (PD-1) receptor blocking monoclonal antibody nivolumab showed encouraging antitumor activity with previously treated mRCC (objective response rate [ORR], 29% (10/34); stable disease at ≥24 weeks [wks], 27% [9/34])62. A randomized, open-label, global phase 3 trial is developed to evaluate the clinical benefit of nivolumab in mRCC pts previously treated (≤2 prior anti-angiogenic therapies and ≤3 total prior systemic regimens) compared to everolimus. The primary endpoint is OS. Secondary endpoints include PFS, ORR, OR duration, adverse events, OS in PD ligand 1 (PD-L1) positive or negative subgroups, and patient-reported outcomes (BMS -936558: NCT01668784).

1.8 Predictive factors

Predictive markers of response to therapy are increasingly important in mRCC due to the proliferation of treatment options in recent years.

Different types of potential predictive markers may include clinical, toxicity-based, serum, tissue, and radiologic biomarkers. Clinical factors are commonly used in overall prognostic models of RCC but have limited utility in predicting response to therapy. Correlation between development of particular toxicities and response to therapy has been noted in several retrospective studies.A lot of angiogenesis-targeted drug, such as bevacizumab, sorafenib, and axitinib, also have shown evidence of association between hypertension and efficacy in RCC, as well as in other tumor types63-66. The mechanism behind this association is not clear, and the possibility exist that development of hypertension may simply correlate with higher drug exposure. Others adverse effects have been interrogated for correlation with efficacy as well, including hand-foot syndrome (HFS), astenia/fatigue, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. In multivariate analysis, treatment related hypertension, HFS, astenia/fatige independently predicted improved efficacy with sunitinib, whereas neutropenia or thrombocytopenia were not independently predictive67-69.

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Retrospective analysis of the phase III temsirolimus trial in RCC demonstred that an increase in cholesterol was associated with an increase in OS for patient treated with temsirolimus. In contrast, changes in blood glucose or triglycerides did not predict a change in survival70.

Factors such as serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and circulating cytokines, including interleukin(IL)-6, IL-8 and ostepontin are potential biomarkers of improved outcome with angiogenesis-targeted therapy71-73.

Finally, baseline or early treatment radiology studies may have predictive ability for longer term efficacy, with most studies to date focusing on functional imaging modalities such as positron emission tomography (PET) scans, dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and DCE ultrasound (US). In one such example, the appearance of marked central necrosis or decreased attenuation to standard RECIST-based measurements was evaluated as a response marker. The authors demonstated that these Mass, attenuation, Size, and Structure (MASS) criteria could be used to identify patients with improved PFS as soon as the first imaging evaluation with much greater accuracy than the simple RECIST. It is not clear that this would be helpful for selecting patients for either early discontinuation/alternative therapy or continued aggressive therapy in clinical practice74.

2.

AIM OF THE STUDY

Hypertension (HTN) is one of the best documented and most frequently observed class-dependent, dose-dependent and additive adverse event of VEGF/VEGFr inhibitors75-77. Patients with baseline

HTN are generally more likely to develop further elevation in blood pressure (BP) when receiving anti-VEGF therapy. The risk of HTN related to anti-VEGF therapy is also higher in patients with mRCC compared to other indications as reported in sorafeniband sunitinib (SU) phase 3 trials78-80.

As a known on-target effect for anti-VEGF agents, HTN has been reported as predictive of better outcome, not only in retrospective analysis81-82. The results of the prospective phase II axitinib first-line study suggests that a change in diastolic BP ≥15 mmHg (day 15, cycle 1) correlates with increased drug exposure and may be associated with an increased response rate. BP may thus provide an indication of the level of exposure to a targeted agent, which in turn appears to be related to efficacy83. BP could potentially act as a surrogate for drug exposure and thus be used by the clinician as a marker to guide dose adjustments for individual patients: axitinib dose titration in patients who tolerate the starting dose of 5 mg twice daily is associated with a greater proportion of patients achieving an objective response versus those who underwent placebo titration84.

The pathophysiological mechanism by which VEGF-pathway inhibition leads to a rise in BP is not fully understood; however, impaired angiogenesis is thought to be central to altered BP control,

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

potentially involving generalised dysfunction of the microcirculation. Activation of the endothelin-1 system, suppression of the renin-angiotensin system, inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and increased vascular stiffness have also been implicated85-89.

Furthermore, a significantly higher incidence of HTN was noted in patients with RCC compared with those with non-RCC malignancies90 and has been reported as a risk factor for developing RCC91-92. However, pre-existing HNT has never been reported as a prognostic factor in mRCC treated with anti VEGF therapy.

Angiotensin System Inhibitors (ASI), including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), are commonly used as antihypertensive and antiproteinuric agents that mediate their effect by the renin-angiotensin system. There has been in vitro and in vivo evidence that angiotensin II is involved in promoting cancer development. Angiotensin II is a powerful mitogen and facilitates cellular growth and proliferation93 through transforming growth factor beta, epidermal growth factor, and tyrosine kinase. Angiotensin II also regulates apoptotic mechanisms and angiogenesis by up-regulating VEGF expression94-95 stimulating neovascularization96 and DNA synthesis97 which is a requirement for tumor growth98. There is

significant evidence that both ACEIs and ARBs may induced cytostatic effects on the cultures of several lines of both normal and neoplastic cells and also delayed the growth of different types of tumors in a variety of experimental animals99-105. These drugs were found to suppress the signal

transduction mediated by growth factors through AT1R antagonism106 and to inhibit the proliferation

of cancer cells through activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ107.

Limited data for their anti-angiogenic effect exists in combinations with targeted therapy. In this study, we aimed to determine whether pre-existing HTN also had prognostic value and whether ASI use correlates with outcome in mRCC patients. We hypothesized that ASI might improve progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with mRCC treated with sunitinib (SU).

3.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

When I was in fellowship at Gustave Roussy, from the RCC database in Institute, we identified 350 mRCC patients who received first-line targeted therapy from April 2004 to November 2013. Among those patients, 239 patients treated with SU have been selected. Twenty-six of them were excluded, because either concomitant immunotherapy and/or incomplete SU first cycle and/or no follow-up information on concomitant medication. Thus, 213 patients were finally enrolled.

Data were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records and paper charts, including the following clinicopathologic information: age, gender, baseline HTN, tumour histology, the time

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

interval from initial diagnosis to sunitinib treatment initiation, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, sites of metastases, laboratory findings, pre-treatment and on treatment blood pressure levels, treatment associated side-effects, sunitinib dose reduction and/or interruption, and treatment outcomes including objective response rate, time to disease progression and overall survival. Data on the concomitant use of medications, including ASI was gathered from patient’s electronic medical records and paper charts documenting baseline patient intake and regular on treatment follow-ups, pharmacy records, and by contacting patients and other treating physicians as needed. Patients were asked about their medications during their first clinic visit and at each follow-up visit, this information was then follow-updated in their medical record. Patients were treated and followed according to current practice guidelines.

All patients were supposed to have progressive disease before starting treatment. Sunitinib was mainly given at a starting dose of 50 mg once a day, in 6-week cycles consisting of 4 weeks on treatment followed by 2 weeks off treatment. Dose reductions or treatment interruptions were performed in case of severe adverse events, depending on their nature and severity, according to standard guidelines. Treatment was continued until evidence of disease progression on scans, unacceptable adverse events, or death. Patient follow-up generally consisted of physical examinations and laboratory assessments (hematologic and serum chemical measurements), at 2 weeks, and then every 6 weeks thereafter, and imaging studies performed every 2 cycles for the first 6 cycles and then every 2 or 3 cycles depending on disease behaviour. For the evaluation of response, the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumours (RECIST) version 1.1 was applied. Baseline HTN was defined as a BP ≥140/90 mmHg before starting SU and/or by the use of an antihypertensive drug. Treatment associated toxicity was evaluated according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events of the National Cancer Institute, version 3.0.

4.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The patients’ characteristics were described by the status of HTN at baseline (patients with history of pre-existing HTN, before SU treatment, were defined HTN_PRE) and ASI users (patients who took ASI before SU treatment initiation or within 1st cycle after SU initiation were defined ASI_PRE and ASI_POST respectively) and compared with Chi2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical data. HTN_POST (defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 140 mm Hg or more, or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 90 mm Hg or more during first cycle of SU) was also considered to confirm the predictive role of better outcome. The different types of anti-hypertensive treatments were reported. A subgroup analysis will be performed in ASI_PRE and ASI_POST. The median follow-up of patients as estimated with the Schemper method. Survival analyses were carried out to examine

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). PFS was defined as the time from SU initiation and tumour progression or death from any cause. Patients who died before experiencing a disease recurrence were censored at their date of death. The prognostic value of HTN and ASI users were assessed in comparing PFS and OS curves estimated from Kaplan-Meier product limit method with log-rank test (univariate analyses) and hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) through a multivariable Cox model adjusted on age, gender, tumour histology, IMDC risk groups and HTN (multivariable analyses). Only pts with a follow-up higher than 1 month and without event in the first month were analysed. Statistical tests were 2-sided and a p-value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.3.

5.

RESULTS

5.1 Patients Characteristics

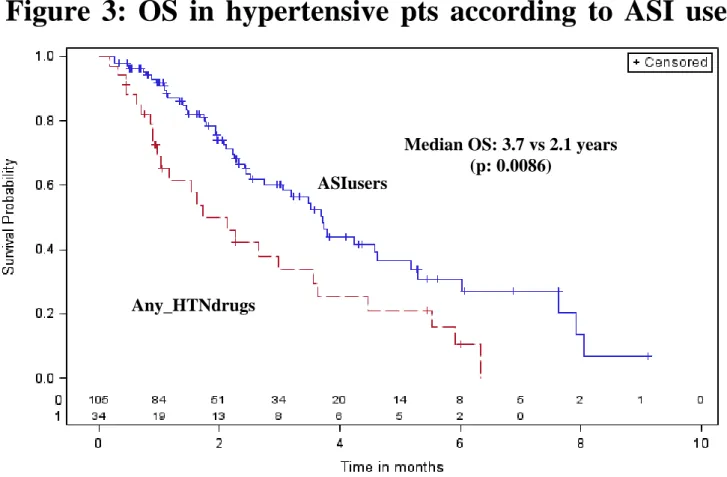

Two hundred and thirteen patients have been recorded. HTN_PRE was found in 88 patients (41%) versus 125 (59%) without HTN_PRE. 105 ASI users (49%) and 108 non-ASI users (51%) were analysed. Median follow-up was 43 months. Median age was 59-years and the majority of patients were male (78%), ECOG PS 0-1 (96%), with clear-cell histology (86%) and intermediate IMDC risk group (61%). Most pts underwent prior nephrectomy (85%). The most common sites of metastases were: lung (54%), bone (22%) and liver (17%). 66% of the pts had more than 1 metastatic site (Table 1). Baseline demographics of HTN_PRE vs non HTN_PRE, as well as those of ASI users vs non-ASI users were similar. 65% of non-ASI users had HTN_PRE vs 19% of non-non-ASI users (p<0.001). Prognostic factors were not significantly different between the groups. The significant differences between the groups were age and antihypertensive non-ASI and ASI use. The most commonly prescribed ASI was ARB (76%), mainly irbesartan (50%) followed by candesartan (12%). 6% of ASI users received ARB/ACE dual blockade (Table 2). In ASI users, patients were ASI_PRE (62,59%) or ASI_POST (43,41%). 139 (65%) pts were hypertensive divided into 88 (63%) HTN_PRE, and 51 (37%) HTN_POST, respectively. Hypertensive pts received ASI (n=105) or not (n=34) based treatment.

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Table 1: Baseline patients characteristics

HTN_PRE ASI users All pts N=213 n (%) No (n=125) n (%) Yes (n=88) n (%) No (n=108) n (%) Yes (n=105) n (%)

Age Mean (Range) 54 (28-79) 64 (38-86) 55 (28-79) 61 (34-86) 58 (28-86)

Gender

Male 97 (78) 68 (77) 83 (77) 82 (78) 165 (77)

Female 28 (22) 20 (23) 25 (23) 23 (22) 48 (23)

ECOG performance status

0-1 122 (98) 83 (94) 105 (97) 100 (95) 205 (96)

≥2 3 (2) 5 (6) 3 (3) 5 (5) 8 (4)

Tumor histology

No clear cell 16 (13) 13 (15) 17 (16) 12 (11) 29 (14) Clear cell 109 (87) 75 (85) 91 (84) 93 (89) 184 (86)

Sites of metastatic disease

Liver 24 (19) 17 (19) 14 (13) 22 (21) 36 (17)

Lung 74 (59) 64 (73) 47 (44) 68 (65) 115 (54)

Bone 21 (17) 22 (25) 17 (16) 29 (28) 46 (22)

Number of site of metastatic >1 85 (68) 73 (83) 57 (53) 83 (80) 140 (66)

IMDC risk group

Low 38 (30) 34 (39) 33 (31) 39 (37) 72 (34) Intermediate 81 (65) 49 (56) 69 (64) 61 (58) 130 (61) High 6 (5) 5 (5) 6 (6) 5 (5) 11 (5) HTN_POST No 79 (63) 46 (52) 93 (86) 32 (30) 125 (59) Yes 46 (37) 42 (48) 15 (14) 73 (70) 88 (41) ASI_PRE No 121 (97) 30 (34) 108 (100) 43 (41) 151 (71) Yes 4 (3)* 58 (66) 0 (0) 62 (59) 62 (29) ASI users No 88 (70) 20 (23) 108 (100) 0 (0) 108 (51) Yes 37 (30) 68 (77) 0 (0) 105 (100) 105 (49) ASI ARB 29 (23) 51 (58) NA 80 (76) 80 (37) ACEI 6 (5) 13 (15) NA 19 (18) 19 (9) ARB+ACEI 2 (2) 4 (5) NA 6 (6) 6 (3)

Non ASI anti-HTN drugs 14 (11) 20 (23) 34 (31) NA 34 (16)

No antihypertensive drugs 74 (59) NA 74 (69) NA 74 (35) ASI users: patients who took ASI before SU treatment initiation or within 1st month after SU initiation

HTN_PRE: patients with history of pre-existing HTN

HTN_POST: defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 140 mm Hg or more, or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 90 mm Hg or more during 1st cycle SU)

*ASI use for renal dysfunction NA/ Not applicable

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Table 2: Types of anti-hypertensive treatments

Drug Pts ARBs Irbesartan Candesartan Olmesartan Losartan Valsartan 54 12 8 7 5 ACEIs Perindopril Ramipril Lisinopril Fosinopril Quinapril Trandonapril 13 4 4 2 1 1

Other anti-hypertensive Beta blocker Calcium antagonist

Beta blocker + calcium antagonist

Beta blocker + calcium antagonist + diuretic

12 12 5 5

5.2 Impact of ASI use

The total number of deaths and events (progression, deaths) was 129 (61%) in ASI users and 184 (87%) in non-ASI users. The median duration of SU treatment for ASI users and non-ASI users was 12.17 months (range: 1.58-54.11) and 6.20 months (range: 1.22-46.78), respectively. HTN_POST (defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 140 mm Hg or more, or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 90 mm Hg or more during SU) was observed in 69% of ASI users and 14% of non-ASI users. In 37% of ASI users was a HTN_POST on HTN_PRE. SU dose was reduced and interrupted for any causes in both cohorts in less than 43% and 30%.

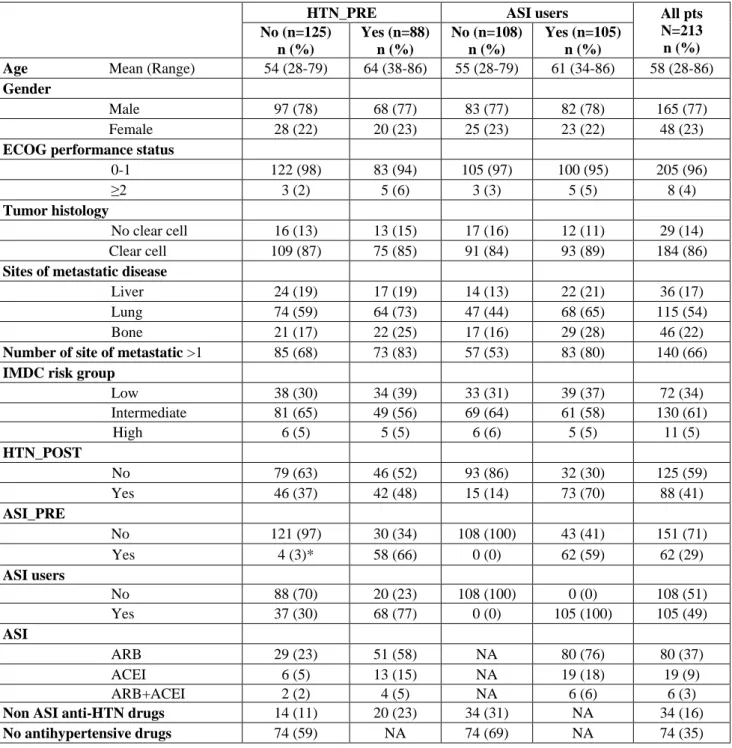

ASI users had a longer OS and PFS compared to patients with non-ASI users: the medians were 3.7 years (range: 2.5-4.6) vs 1.5 (range: 1.0-1.9) for OS (p<.0001) and 1.2 (range: 0.9-1.4) vs 0.6 (range: 0.4-0.7) for PFS (p=0.002). (Figure 1 and 2).

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Figure 1: OS according to ASI use

Figure 2: PFS according to ASI use

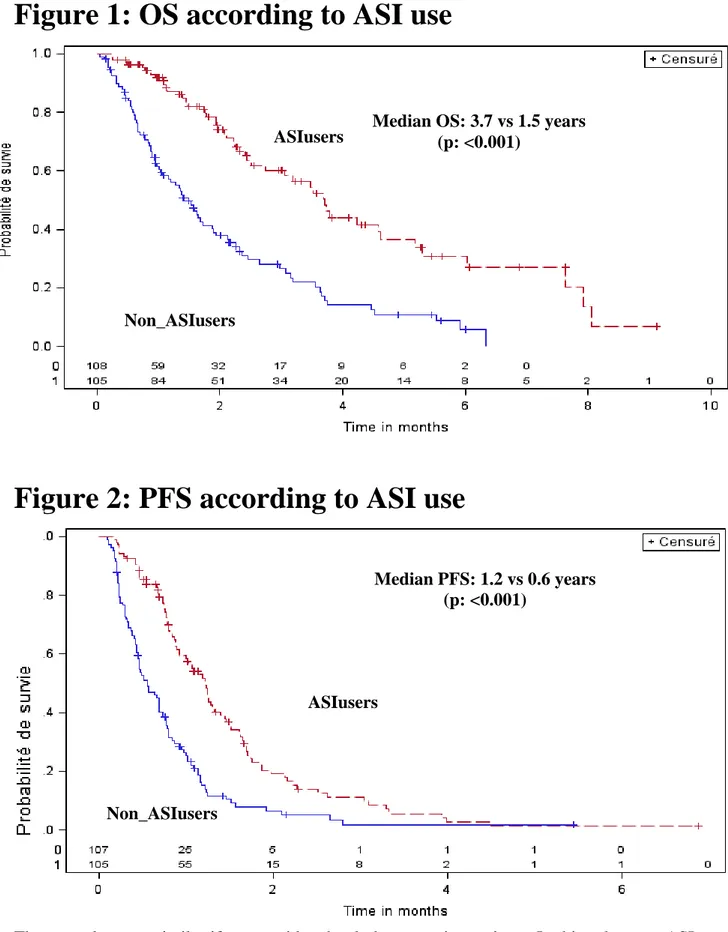

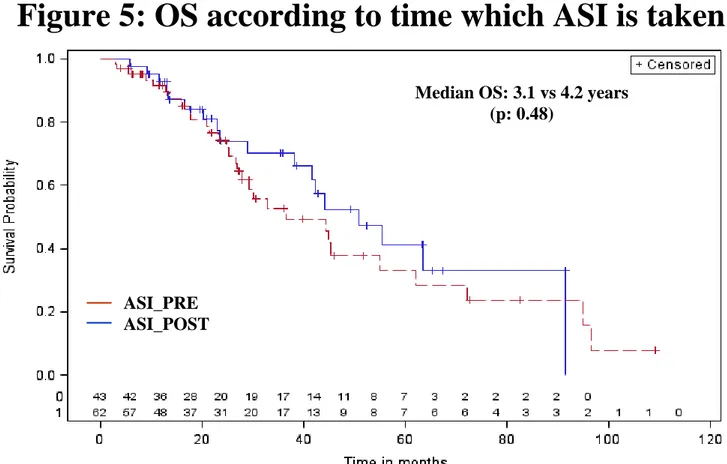

These results were similar if we considered only hypertensive patients. In this subgroup, ASI users were compared with Any_HTNdrugs (patients who took any drugs for HTN, not ASI): the medians were 3.7 years vs 2.1 for OS (p=0.0086) and 1.2 vs 0.7 years for PFS (p=0.047) (Figure 3 and 4). Among ASI users (n=105), 62 were ASI_PRE and 43 ASI_POST. OS (HRprior/post=0.80 [0.41-1.57], p=0.51) and PFS (HR=0.84 [0.52-1.34], p=0.46) were not significantly different between

Median OS: 3.7 vs 1.5 years (p: <0.001) Non_ASIusers ASIusers ASIusers Non_ASIusers Median PFS: 1.2 vs 0.6 years (p: <0.001)

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

ASI_PRE and ASI_POST (Figure 5 and 6). After adjustment for age, gender, histology, IMDC prognostic group, HTN_PRE, HTN_POST, ASI users remained significantly associated with favourable outcomes (Table 3).

Figure 3: OS in hypertensive pts according to ASI use

_HTNdrug

Figure : PFS in ASI users vs Any_HTN drugs

Figure 4: PFS in hypertensive pts according to ASI use

Table 3: Prognostic value of ASI use

ASIusers

Any_HTNdrugs

Median OS: 3.7 vs 2.1 years (p: 0.0086)

ASIusers

Any_HTNdrugs

Median PFS: 1.2 vs 0.7 years (p: 0.047)

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Figure 5: OS according to time which ASI is taken

Figure 6: PFS according to time which ASI is taken

Median OS: 3.1 vs 4.2 years (p: 0.48) Median PFS: 1.25 vs 1.25 years (p: 0.75) ASI_PRE ASI_POST ASI_PRE ASI_POST

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Table 3: Prognostic value of ASI use (multivariable

analyses)

OS PFS HR 95%CI p HR 95%CI P Age 1.02 1.00-1.04 0.136 1.01 0.99-1.03 0.327 Gender Male 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Female 1.49 0.96-2.33 0.77 1.34 0.93-1.92 0.115 Histology Clear cell 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Non 1.13 0.69-1.85 0.630 1.38 0.89-2.14 0.154 IMDC prognostic groupPoor 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Good 0.06 0.03-0.13 < 0.0001 0.12 0.06-0.25 0.0001 Intermediate 0.14 0.07-0.30 0.001 0.26 0.14-0.51 0.0001 HTN_PRE No 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Yes 0.70 0.44-1.12 0.135 0.75 0.51-1.08 0.122 HTN_POST No 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Yes 0.68 0.43-1.07 0.098 0.82 0.56-1.19 0.298 ASI use No 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Yes 0.41 0.25-0.68 0.0005 0.51 0.34-0.78 0.002

5.3 Impact of HTN

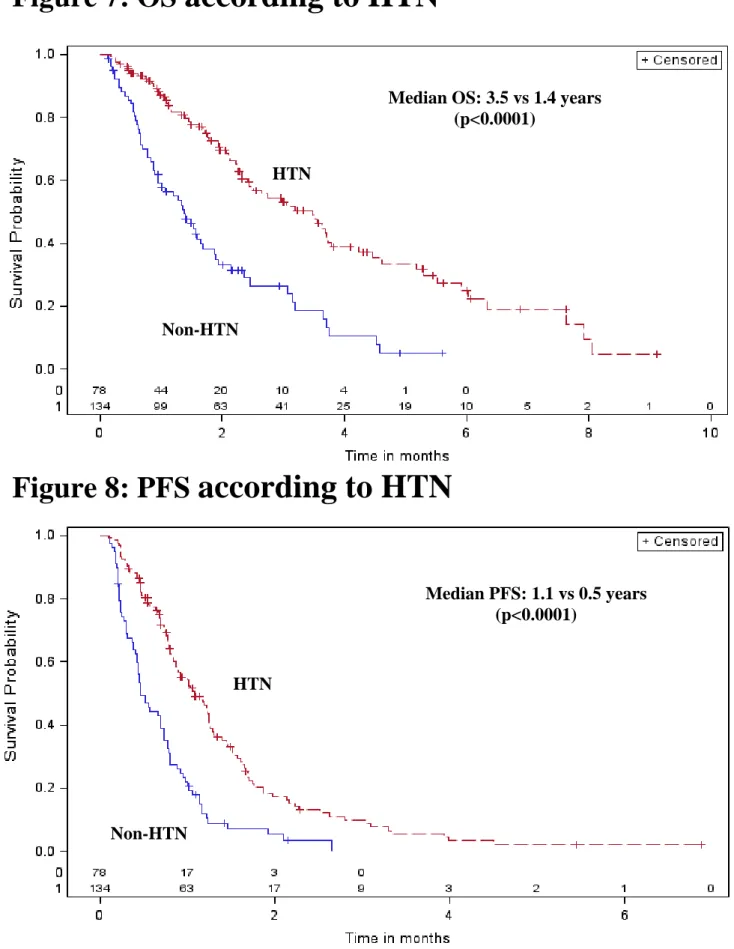

134 (63%) pts were hypertensive divided into 88 (41%) HTN_PRE, and 46 (22%) HTN_POST (SU related HTN), respectively. Hypertensive pts have longer OS (median: 3.5 vs 1.4 years, p<0.0001) and longer PFS (median: 1.1 vs 0.5 years, p<0.0001) than non-hypertensive pts (n=79) (Figure 7 and 8). After adjustment for age, gender, histology, IMDC prognostic group, hypertensive patients and ASI use, HTN is an independent prognostic factor (marginal) for OS and PFS in pts with mRCC treated with SU (Table 4).

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Figure 7: OS according to HTN

Figure 8: PFS according to HTN

Median OS: 3.5 vs 1.4 years (p<0.0001)

HTN

HTN Non-HTN HTN Non-HTN Median PFS: 1.1 vs 0.5 years (p<0.0001)Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Table 4: Prognostic value of HTN (multivariable

analyses)

OS PFS HR 95%CI p HR 95%CI P Age 1.02 1.00-1.04 0.11 1.01 0.99-1.03 0.327 Gender Male 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Female 1.48 0.95-2.30 0.08 1.34 0.93-1.90 0.115 Histology Clear cell 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Non 1.19 0.71-1.97 0.50 1.48 0.92-2.26 0.11 IMDC prognostic groupPoor 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Good 0.55 0.24-0.122 < 0.0001 0.13 0.06-0.26 <0.0001 Intermediate 0.14 0.07-0.28 < 0.0001 0.26 0.14-0.51 <0.0001 ASI use No 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Yes 0.41 0.24-0.66 0.004 0.55 0.35-0.86 0.009 HTN No 1.00 - - 1.00 - - Yes 0.602 0.36-1.003 0.05 0.63 0.40-1.01 0.05

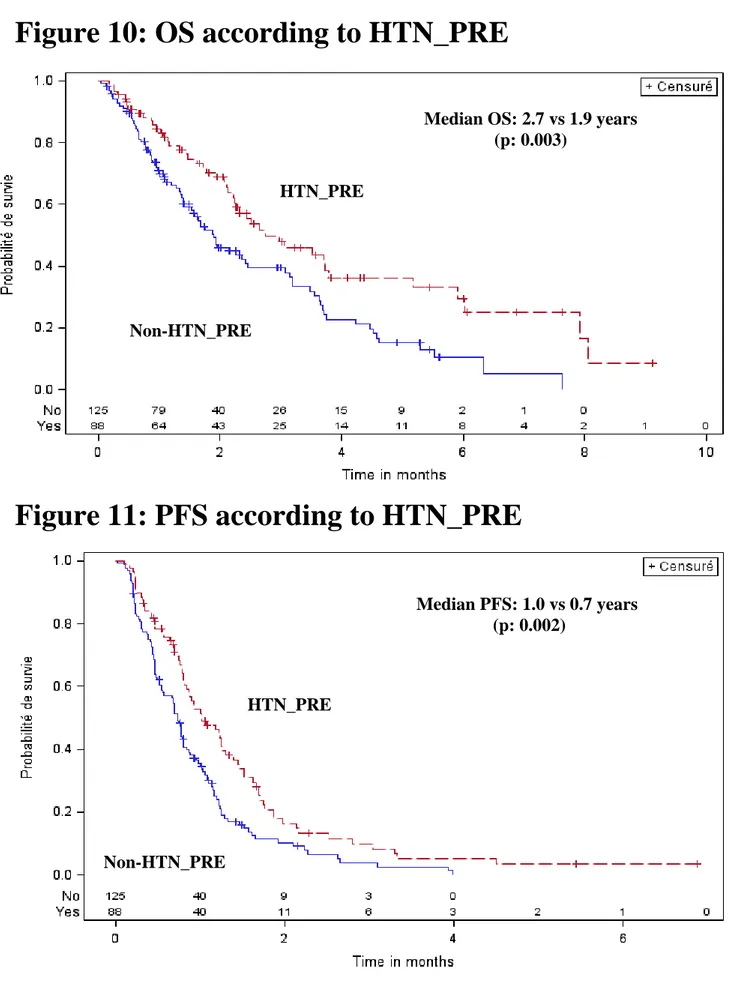

For clinical reasons, it is interesting to distinguish hypertensive patients PRE or POST SU treatment. HTN_PRE had a longer OS and PFS compared to patients non-HTN_PRE: the medians were 2.7 years (range: 2.2-3.8) vs 1.9 (range:1.5-2.5) for OS (p=0.003) and 1.0 (range: 0.8-1.3) vs 0.7 (range: 0.5-0.8) for PFS (p=0.002) respectively (Figure 10 and 11). However, HTN_PRE were more often ASI_PRE (66%) compared to patients with non-HTN_PRE (3%) (p<0.0001). The four (3%) pts ASI_PRE without HTN_PRE were pts with chronic renal failure. In HTN_PRE subgroup, OS and PFS were not significantly different between ASI_PRE and non-ASI_PRE.

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

Figure 10: OS according to HTN_PRE

Figure 11: PFS according to HTN_PRE

Patients with HTN_POST had better outcomes than those without HTN_POST: the medians were 3.6 years vs 1.6 for OS (p<0.0001) and 1.2 vs 0.7 for PFS (p=0.0002) respectively (Figure 12 and 13).

Median OS: 2.7 vs 1.9 years (p: 0.003) Non-HTN_PRE HTN_PRE Median PFS: 1.0 vs 0.7 years (p: 0.002) Non-HTN_PRE HTN_PRE

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

The patients HTN_POST and ASI users had better outcomes than those with HTN_POST and non ASI users. The patients HTN_POST and ASI users had better outcomes than those with non-HTN_POST and non ASI users (p<0.0001).

Figure 12: OS according to HTN_POST

Figure 13: PFS according to HTN_POST

Median OS: 3.6 vs 1.6 years (p < 0.0001) HTN_POST Non-HTN_POST Median PFS: 1.2 vs 0.7 years (p: 0.0002) HTN_POST Non-HTN_POST

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

6.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

The present study suggests that concomitant use of ASI may improve the outcome of SU treatment in mRCC. In this retrospective study, patients receiving ASI, before or within one cycle of SU treatment, had a significant 0.6 years increase of the PFS (p=0.002) and 2.2 years increase of OS compared to patients with non-ASI users (p= <.0001). The results were similar if ASI users were compared with any other drugs for HNT. After adjustment for risk factors, ASI use remained significantly associated with favourable outcomes.

The role of ASI has been contradictory: in existing preclinical and clinical data sometimes is defined as a risk factor of developing cancer, sometimes is associated with improved clinical outcomes in several cancer types. The reported data regarding the effect of ASI as a risk factor of developing cancer are inconclusive.

Early limited meta-analysis of selected ARB trials (90 000 individuals in eight trials) suggested a small increase in the risk of cancer, particularly of the lung, prostate and possibly breast108. Since then, several larges meta-analyses (15 trials on nearly 140 000 participants) have reported that in contrast with this earlier work, there was no evidence of an excess risk of cancers associated with long-term ARB therapy109-111 even improving outcomes in cancer patients in systematic review112. Furthermore, ACEI has been suggested to protect against cancer ever since Lever et al.’s landmark report in 1998 of a 28% reduced cancer incidence among ACEI users compared with general control subjects113. Makar et al found that long-term use of ACE-Is/ARBs, particularly at high-dose, was

associated with reduced colorectal cancer risk in a cohort of patients with HTN114.whereas, Friis et

al. found a standardized incidence ratio for overall cancer of 1.07 (95% CI = 1.01 to 1.15) in a cohort study of 17 897 ACE-I users followed for an average of 3.7 years115. Our findings are concordant

with Menamim review’s who fond an improvement in PFS in patients with RCC (HR 0.54, p = 0.02) under ASI treatment112.

Similar beneficial effects of ASI were reported with various cancer types. In a xenograft model, of glioma Rivera et al.116 reported that losartan reduced tumor volume by 79% in C6 rat glioma by significantly decreasing vascular density, mitotic index, and cell proliferation.

ASI, in combination with conventional chemotherapeutic reagents such as gemcitabine, might be associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer117 Telmisartan has been reported to have antiproliferative activity in prostate cancer and RCC118-120 and might be a therapeutic option for the treatment of endometrial cancers121.

The antineoplastic effect of ASI maybe exerted by reduction/inhibition of angiotensin II synthesis. The Accumulating data indicate that the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), is frequently deregulated in malignancy. Evidence indicates that the inhibition of the RAS is protective rather than deleterious

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

with regard to the development of cancer. It has been shown that components of the RAS are expressed in cancer cells from various tissues including the lungs, kidneys, breast, and prostate122.

Further, angiotensin II has been shown to have a local effect on cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and inflammation, in addition to its well-known systemic effects on the cardiovascular system. These local effects are mediated by the angiotensin II type 1 receptor or the angiotensin II type 2 receptor, which have different tissue distribution. The main effect of ARBs on cancer appears to be through inhibition of the release of pro angiogenic factors from tumor cells in vitro123. This has been observed with candesartan in various cancer cell lines124-126. Decrease in the expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 has also been observed127-129. This effect could be mediated by an inhibitory effect of ARB on hypoxia-inducible-factor and ETS-1 induction, which has been reported in hormone refractory prostate cancer cell lines130. Furthermore, recent in vivo evidence demonstrates that ASI administration substantially reduces the total number of colonic premalignant lesions and decreases oxidative stress and expression of inflammatory cytokines in metabolically disordered mice, suggesting that suppression of inflammation might mediate the effect downloaded from of RAS inhibitors against colorectal carcinogenesis131. In addition, treatment with ASI and

cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors has been shown to suppress expression of insulin-like growth factor I receptor in colon cancer cells and reduce tumor growth in vivo132.

All these existing preclinical and clinical data support our work but our study is of special interest because this is the largest series of patients treated with SU as first line treatment, where both pre-existing HTN and use of ASIs are reported. The monocentric aspect of the study enables us to have accurate information regarding HTN, concomitant medications, adverse events and outcome. For the first time, we report that baseline HTN is an independent prognostic factor, we confirm that HTN_PRE is a predictive factor of better outcome and that mRCC patients using ASIs have a significantly longer PFS and OS, when treated with SU. The potential benefit of ASI in mRCC patients has been already reported in an abstract form presented at ASCO GU this year: Rana R. McKay has conducted a multicentric, retrospective analysis of pts with mRCC treated on phase III and II clinical trials and treated with ASI at baseline or within the first 30 days of study. She used a clinical trials database for collect data, not performed expressly for evaluate the role of ASIs on outcome. The pts in this report were treated with different anti-VEGF agents not only in first line and about one-third of patients (33%) had prior systemic therapy. In our experience the data on the concomitant use of medications, including ASI was gathered from patient’s electronic medical records and paper charts documenting baseline patient intake and regular on treatment follow-ups, pharmacy records, and by contacting patients and other treating physicians as needed133.

Our study confirms that the use of ASI (ACE/ARB) is related with OS and PFS improvement in mRCC pts receiving SU as first line. There is no difference on outcome between pts who receive ASI

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

before starting SU and those who received ASI only within one cycle of SU. This observation might suggest that patients who develop HTN should be treated with ASI. ASI may have an additive or synergistic anti-angiogenic effect in combinations with SU. ASI may be the anti-hypertensive treatment of choice form RCC pts without contraindication.

There are several limitations of the current investigation. Some patients were given ASI for HTN_POST, considered a true biomarker of efficacy in this setting and it is not entirely clear how this affects the data. Further studies are warranted to confirm that ASI use is really related with outcome and not simply an epiphenomenon of higher drug exposure, related at better control of HTN, a possibility that cannot be definitively excluded given the inherent limitations of a retrospective analysis.

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

7.

REFERENCES

1. Siegel R., et al. Cancer statistics 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Jan;63(1):11-30.

2. Yagoda A., et al. Cytotoxic chemotherapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma. The Urologic clinics of North America 1993 20, 303-321.

3. Kjaer M., et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in stage II and III renal adenocarcinoma. A randomized trial by the Copenhagen Renal Cancer Study Group. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics 1987 13, 665-672.

4. Motzer R.J., et al. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 1999 17, 2530-2540.

5. Rini B., et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet 2009 373(9669):1119-1132.

6. Kovacs G., et al. The Heidelberg classification of renal cell tumours. The Journal of pathology 1997 183, 131-133.

7. Argani P., et al. Aberrant nuclear immunoreactivity for TFE3 in neoplasms with TFE3 gene fusions. A sensitive and specific immunohistochemical assay. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:750-761.

8. Ro J.Y., et al. Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: clinicopathologic. A study of 42 cases. Cancer 1987 59, 516-526.

9. Siegel R., et al. Cancer statistics 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Jan;63(1):11-30.

10. Hunt J.D., et al. Renal cell carcinoma in relation to cigarette smoking: meta-analysis of 24 studies. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 2005 114, 101-108. 11. Yuan J.M., et al. Tobacco use in relation to renal cell carcinoma. Cancer epidemiology,

biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 1998 7, 429-433.

12. McLaughlin J.K., et al. International renal-cell cancer study. I. Tobacco use. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 1995 60, 194-198.

13. Chow W.H., et al. Obesity, hypertension, and the risk of kidney cancer in men. The New England journal of medicine 2000 343, 1305-1311.

14. McLaughlin J.K., et al. International renal-cell cancer study. VIII. Role of diuretics, other anti-hypertensive medications and hypertension. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 1995 63, 216-221.

15. Mellemgaard A., et al. International renal-cell cancer study. III. Role of weight, height, physical activity, and use of amphetamines. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 1995 60, 350-354.

16. Lee J.E., et al. Intakes of fruit, vegetables, and carotenoids and renal cell cancer risk: a pooled analysis of 13 prospective studies. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2009 18, 1730-1739.

17. Lipworth L., et al. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. The Journal of urology 2009 176, 2352353-2358.

18. Mancuso A., et al. New treatments for metastatic kidney cancer. The Canadian journal of urology 2005 12, 66-70;105.

19. Flanigan R.C., et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Current treatment options in oncology 4, 385-390 (2003).

20. Cheville J.C., et al. Comparisons of outcome and prognostic features among histologic subtypes of renal cell carcinoma. The American journal of surgical pathology 2003 27, 612-624.

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

21. Lara P.J., et al. Kidney Cancer in Principles and Practice. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2012.

22. Skinner D.G., et al. Diagnosis and management of renal cell carcinoma. A clinical and pathologic study of 309 cases. Cancer 1971 28, 1165-1177.

23. Gupta N.P., et al. Renal tumors presentation: changing trends over two decades. Indian journal of cancer 2010 47, 287-291.

24. Jayson, M., et al. Increased incidence of serendipitously discovered renal cell carcinoma. Urology 1998 51, 203-205.

25. Ljungberg B., et al. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2012 update. European urology 58, 398-406.

26. Peycelon M., et al. Long-term outcomes after nephron sparing surgery for renal cell carcinoma larger than 4 cm. The Journal of urology 2009 181, 35-41.

27. Mancuso A., et al. New treatments for metastatic kidney cancer. The Canadian journal of urology 2005 12, 66-70;105.

28. Flanigan R.C., et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Current treatment options in oncology 2003 4, 385-390.

29. Rathmell W.K., et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Current opinion oncology 2007 19, 234-240. 30. Bianchi M., et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in renal cell carcinoma: a population-based

analysis. Annals of oncology 2012 23, 973-980.

31. Snow R.M., et al. Spontaneous regression of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urology 1982;20:177–81.

32. Flanigan R.C., et al. Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2001 345, 1655-1659.

33. Mickisch G.H., et al. Radical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001 358, 966-970.

34. Flanigan R.C. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in metastatic renal cancer. Current urology reports 2003 4, 36-40.

35. Choueiri T.K., et al.The impact of cytoreductive nephrectomy on survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy. J Urol. 2011;185(1):60-66.

36. Barbastefano J., et al. Association of percentage of tumour burden removed with debulking nephrectomy and progression-free survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. BJU Int. 2010;106(9):1266-1269.

37. Heng D.Y.C., et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) in patients with synchronous metastases from renal cell carcinoma: Results from the International Metastatatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC). Genitourinary Cancers Symposium 2014. Abstract 396. 38. Alt A.L., et al. Survival after complete surgical resection of multiple metastases from renal cell

carcinoma. Cancer. 2011 Jul 1;117(13):2873-82.

39. Volpe A., et all. Prognostic Factors in Renal Cell Carcinoma. World Journal of Urology 2010, 28(3) 319-327.

40. Méjean A., et al. Prognostic factors of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2003 Mar;169(3):821-7. 41. Lam J.S., et al. Prognostic factors and selection for clinical studies of patients with kidney

cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008 Mar;65(3):235-62.

42. Iacovelli R., et al. Tumour burden is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2012;110(11):1747-53.

Lisa Derosa: Hypertension: prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Tesi di Specializzazione in Oncologia Medica – Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia - Università di Pisa

43. Motzer R.J., et al. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Aug;17(8):2530-40.

44. Heng D.Y., et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor- targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. JCO 2009 27(34):5794-5799.

45. Vuky J., et al. Cytokine therapy in renal cell cancer. Urologic oncology 2000 5, 249-257. 46. Pyrhonen S., et al. Prospective randomized trial of interferon alfa-2a plus vinblastine versus

vinblastine alone in patients with advanced renal cell cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 1999 17, 2859-2867.

47. Coppin C., et al. Immunotherapy for advanced renal cell cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2005, CD001425.

48. Fyfe G., et al. Results of treatment of 255 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 1995 13, 688-696.

49. Adnane L., et al. Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006, Nexavar), a dual-action inhibitor that targets RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in tumor cells and tyrosine kinases VEGFR/PDGFR in tumor vasculature. Methods in enzymology 2006 407, 597-612.

50. Motzer R.J., et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alpha in renal cell carcinoma. New England journal of medicine 2007 356:115-124.

51. Hutson T.E., et al. Targeted therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an overview of toxicity and dosing strategies. The oncologist 2008 13, 1084-1096.

52. Ranieri G., et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as a target of bevacizumab in cancer: from the biology to the clinic. Current medicinal chemistry 2006 13, 1845-1857. 53. Escudier, B., et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell

carcinoma: a randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet 2007 370, 2103-2111.

54. Akaza H., et al. Axitinib for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy 2014 15, 283-297.

55. Rini B.I., et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011 378, 1931-1939.

56. Gupta S., et al. The prospects of pazopanib in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Therapeutic advances in urology 2013 5, 223-232.

57. Sternberg C.N., et al. A randomised, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in patients with advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final overall survival results and safety update. European journal of cancer 2013 49, 1287-1296.

58. Otto T., Eimer, C. & Gerullis, H. Temsirolimus in renal cell carcinoma. Transplantation proceedings 2008 40, S36-39.

59. Hudes G., et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2007 356, 2271-2281.

60. Motzer R.J., et al. Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer 2010 116, 4256-4265.

61. Choueiri T.K., et all. A phase I study of cabozantinib (XL184) in patients with renal cell cancer. Annals oncology 2014 May 24.

62. Topalian S.L., et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012 366, 2443–2454.

63. Rini B.I., et al. Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:763-73.

64. Bamias A., et al. Diagnosis and management of hypertension in advanced renal cell carcinoma: prospective evaluation of an algorithm in patients treated with sunitinib. J Chemother. 2009;21: 347–50.