PhD Course

Politics, Human Rights

and Sustainability

(DIRPOLIS Institute)

Academic Year

2017/2018

Human Rights in Foreign Policy – an

Analysis of Counter-Piracy Discourse

and Policies of the European Union

and the United States of America

Author

Gergana Tzvetkova

Supervisor

ii

Table of Contents

LIST OF TABLES ... v

LIST OF CHARTS ... vi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ... vii

ABBREVIATIONS ... ix

CHAPTER 1 TOPIC AND METHODOLOGY ... 1

1.1 Research Questions ... 1

1.1.1 Introduction ... 1

1.1.2 Research Question, Foundational Assumptions and Main Argument ... 2

1.2 Units of Analysis and Case Study ... 4

1.2.1 The EU and the US – a Needed Comparison ... 4

1.2.2 Somali Piracy as a Case Study ... 6

1.3 Constructivist Research Framework ... 9

1.3.1. The Constructivist Research Programme ... 9

1.3.2 Main Constructivist Premises ... 13

1.3.2.1 Mutual Constitution of Agents and Structures ... 13

1.3.2.2 The Relevance of the Social and the Historical ... 14

1.3.2.3 Communication Matters ... 16

1.3.2.4 The Importance of Values ... 17

1.4 Values, Norms and Interests ... 18

1.4.1 Values ... 18

1.4.2 Norms ... 20

1.4.3 Ideational Influence on Interest Formation ... 23

1.5 Foreign Policy and Role Theory ... 24

1.5.1 Constructivist Contribution to Foreign Policy Analysis ... 24

1.5.2 Identity and Roles of Actors ... 27

1.6 Contribution and Limits of the Research ... 30

1.6.1 Identified Limits ... 30

1.6.2 Contribution of the Research ... 31

1.7 Methodology ... 32

1.7.1 Methodological Considerations ... 32

1.7.2 Text Analyses ... 34

1.7.3 Text Selection and Classification ... 36

1.7.4 The Questions Asked... 38

1.7.5 Discourse Historical Approach ... 42

CHAPTER 2 HUMAN RIGHTS AND FOREIGN POLICY IN THE EU AND THE US ... 48

2.1 The Lifecycle of Human Rights ... 48

iii

2.1.2 The Philosophical Grounds ... 49

2.1.3 The Legal Stage ... 52

2.1.4 Human Rights Enter Foreign Policy ... 54

2.2 Human Rights in EU Foreign Policy – a Timeless System of Values ... 57

2.2.1 The Influence of the Enlightenment ... 57

2.2.2 The World Wars and the “Tragedy of Europe” ... 59

2.2.3 The EU as a “Community of Values” ... 62

2.2.4 EU’s Powers ... 64

2.3 The ideals that still light the world – the United States and Human Rights ... 66

2.3.1 Traditions and Presidents ... 66

2.3.2 The Founding Rights and their Guardians ... 68

2.3.3 From Isolation to Rights Exportation ... 69

2.3.4 A Permanent Association with Human Rights ... 71

2.3.5 Difficult Times for Human Rights ... 73

CHAPTER 3 THE EUROPEAN UNION – A GLOBAL ACTOR IN COUNTER-PIRACY ... 77

3.1 EU and Somali Piracy – the Background ... 77

3.2 Documents Analysis: Sources, Strategy, and Methods ... 79

3.2.1 Criteria for the Selection of Documents ... 79

3.2.2 General Classification of Documents ... 80

3.2.3 General Documents ... 81

3.2.4 Naval Operations and Maritime Programmes ... 82

3.2.5 Transfer Agreements and the CGPCS ... 83

3.3 The Findings ... 84

3.3.1 The Conceptual Analysis ... 84

3.3.1.1. Attributes and Connotation ... 84

3.3.1.2. The Concept Pairs ... 87

3.3.1.3. The European Union Roles ... 92

3.3.2 The Discourse Analysis ... 94

3.3.2.1 Intertextuality, Interdiscursivity, and Levels of Context ... 94

3.3.2.2 Discourse Strategies in EU Discourse ... 95

3.3.2.2.1 Nomination and Predication Strategies ... 95

3.3.2.2.2 Argumentation Strategy and Topoi ... 98

3.3.2.2.3 Perspectivation Strategy and Roles ... 102

3.3.2.2.4 Intensification/Mitigation Strategies ... 104

3.3.3 Policy Focus ... 105

CHAPTER 4 US COUNTER-PIRACY EFFORTS – LEADERSHIP AND RESPONSIBILITY TO PROSECUTE ... 110

4.1 The US and Somali Piracy – the Background ... 110

iv

4.2.1 Criteria for the Selection of Documents ... 112

4.2.2 General Classification of Documents ... 113

4.2.3 General Documents ... 114

4.2.4 Legislative, Judicial, and Policy Documents ... 114

4.2.5 Official Statements and Remarks ... 115

4.3 The Findings ... 116

4.3.1 The Conceptual Analysis ... 116

4.3.1.1. Attributes and Connotation ... 116

4.3.1.2. The Concept Pairs ... 119

4.3.1.3. The Roles of the United States ... 123

4.3.2 The Discourse Analysis ... 126

4.3.2.1 Intertextuality, Interdiscursivity, and Levels of Context ... 126

4.3.2.2 Discourse Strategies in the US Discourse ... 128

4.3.2.2.1 Nomination and Predication Strategies ... 128

4.3.2.2.2 Argumentation Strategy and Topoi ... 130

4.3.2.2.3 Perspectivation Strategy and Roles ... 134

4.3.2.2.4 Intensification/Mitigation Strategies ... 136

4.3.3 Policy Focus ... 136

CHAPTER 5 RESEARCH FINDINGS: US AND THE EU – ALMOST ALIGNED BUT NOT THERE YET ... 140

CONCLUSION ... 148

REFERENCES ... 153

APPENDICES ... 172

Appendix 1 List of analysed documents originating from the European Union ... 172

Appendix 2 List of Analysed Documents originating from the United States of America ... 181

Appendix 3 Code Book Applied to EU Discourse Generated by Atlas.ti Software ... 189

v LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Discourse strategies – questions and tools ... 45

Table 2 Linguistic tools – definitions and examples ... 45

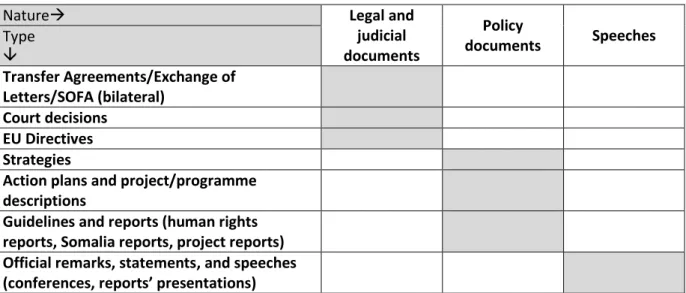

Table 3 Analysed EU Documents ... 80

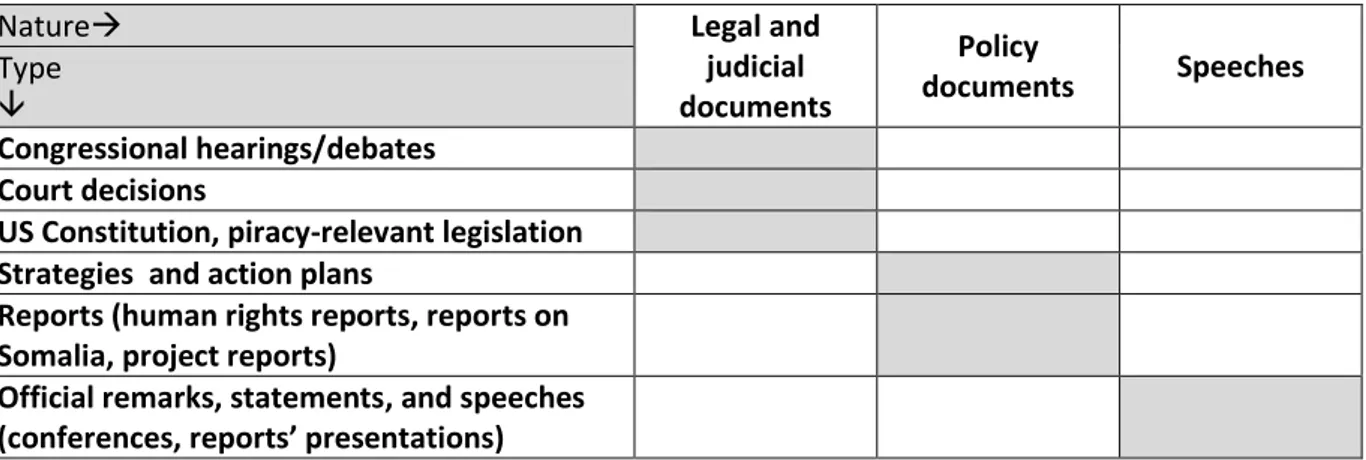

Table 4 Analysed US Documents ... 113

Table 5 Content Analysis – Main Findings ... 142

Table 6 Observations following the Content Analysis ... 143

vi LIST OF CHARTS

Chart 1 Attributes - adjectives paired with rights ... 39

Chart 2 Actions – verb references ... 39

Chart 3 Concepts paired with rights ... 40

Chart 4 Rights as described in terms of interests, values/principles or norms ... 40

Chart 5 Attributes – adjectives paired with rights (European Union) ... 85

Chart 6 Actions – verb references (European Union) ... 87

Chart 7 Concepts paired with rights (European Union) ... 88

Chart 8 Rights as described in terms of interests, values/principles or norms (European Union) ... 91

Chart 9 The European Union – the Roles ... 92

Chart 10 The European Union – the Roles, Concise ... 93

Chart 11 Attributes – Adjectives Paired with Rights (United States) ... 117

Chart 12 Actions – Verb References (United States) ... 118

Chart 13 Concepts Paired with Rights (United States) ... 120

Chart 14 Rights as Described in Terms of Interests, Values/Principles or Norms (United States) ... 123

Chart 15 United States of America – the Roles ... 124

vii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This thesis examines the conceptualisation of human rights and their utilisation in foreign policy formulation and implementation by the United States of America (USA) and the European Union (EU). We focus on analysis of discourse and policies related to counter-piracy in Somalia during the period 2008-2016. This research adopts a qualitative research approach. It reflects an interest in the meanings behind concepts. We rely on premises, tools and insights provided by the constructivist approach to international relations, role theory and foreign policy analysis. We argue that there are differences in the way the EU and the US articulate and operationalise human rights. These differences result from the two actors’ different prioritisation and interpretation of underlying political values and the international roles they envisage for themselves. We seek the grounds for the differences in predominant philosophical ideas, legal traditions and historical and social contexts. From a methodological point of view, the research employs a combination of content and discourse analyses.

Chapter 1 introduces our research question and main argument. It justifies the selection of units of analysis, the case study and the period of time considered. It explains the research framework and methodology. It argues why constructivism and role theory were deemed fitting for this kind of research.

Chapter 2 deals with the conceptualisation of human rights from a philosophical and legal perspective in a diachronic perspective. It also discusses the incorporation of human rights in foreign policy. The chapter presents the development of the human rights concept in the EU and the US respectively. This is supported by a discussion of major foreign policy traditions and roles adopted by the two actors.

Chapter 3, on the EU, and Chapter 4, on the US, constitute the core of the analysis. Both chapters begin with a presentation of the documents that were selected for the content and discourse analyses. The study aims at identifying key elements of human rights conceptualisation and the crossing points between the concepts of human rights and counter-piracy. Both chapters in their final part indicate what are the main features and directions of EU and US counter-piracy policies.

viii

Chapter 5 presents the main findings of our research in a comparative perspective. The United States’ and the European Union’s ways of conceptualising and utilising the concept of human rights are discussed side by side in order to identify associated similarities and differences.

The Conclusion summarises the main findings of the research including theoretical and policy implications. It further sets some possible targets for future research, inspired and informed by the analysis and findings presented in this thesis.

ix

ABBREVIATIONS

BMP Best Management Practices

CA Content Analysis

CAT Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

CFSP Common Foreign and Security Policy

CGPCS Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia

CMR Critical Maritime Routes Programme

CoE Council of Europe

CSDP Common Security and Defence Policy

CTF Combined Task Force

DA Discourse Analysis

DHA Discourse Historical Analysis

ECHR European Convention on Human Rights

ECtHR European Court of Human Rights

EEAS European External Action Service

EP European Parliament

EU European Union

EUGS European Union Global Strategy

FPA Foreign Policy Analysis

HoR House of Representatives

HRVP High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy/ Vice-President of the Commission

ICC International Criminal Court

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

IfS Instrument for Stability

IHRL International Human Rights Law

IL International Law

IR International Relations

MASE Programme to Promote Regional Maritime Security

MoU(s) Memorandum/Memoranda of Understanding

MPJM Maritime Piracy Judicial Monitor

NRC National Role Conception

NSS National Security Strategy

R2P Responsibility to Protect

UDHR Universal Declaration of Human Rights

UN United Nations

UNCLOS United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

UNGA United Nations General Assembly

UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

USA United States of America

WWI World War I

1

CHAPTER 1 TOPIC AND METHODOLOGY

1.1 Research Questions

1.1.1 Introduction

In the wake of the 2013 revelations about the spying of agencies of the United States of America (USA) on Angela Merkel and other European leaders, the German Chancellor commented: “We need trust […] Spying among friends is never acceptable” (Smith-Spark, 2013). Months later, when more details about surveillance were disclosed, President Obama stated: “We’re not perfectly aligned yet, but we share the same values, and we share the same concerns” (Landler, 2014). Within the European Union (EU) itself, the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, warned then British Prime Minister David Cameron that “the fundamental values of the European Union are not for sale and so are non-negotiable” (Watt, The Guardian, 2015). Political leaders often resort to shared values and notions like friendship, trust, fear in order to explain, defend or justify their standpoints and decisions. The EU and the US1 are not an exception. Both actors consider as their inherent values the respect for human rights, rule of law, democracy and dignity.

However, US and EU reactions to critical situations demonstrate how difficult it is to define values and translate them into actions. In the last decades, the US has been criticised for the War on Terror, the drone strikes, the mass surveillance, the failure to close Guantanamo prison. The EU has been accused of double standards and failure to take effective action in some crises (like the economic or the migrant one). Clearly, the topic of values is persistently present in both national and international political discourses.

The present work relies on two premises largely discussed within the constructivist approach to international relations (IR). The first one concerns the importance of ideational factors like ideas and values for the definition of state interests and foreign policy. The ideational factor under scrutiny here is the concept of human rights. The second premise is the significance of language, and more specifically discourse, and the need to analyse it for understanding and interpreting state behaviour. The emphasis on language as a key to understand politics has determined our research method – a combination of content and discourse analyses. In particular, we will study the discourse on counter-piracy policy of the US and the EU.

1

In the thesis, we mainly use EU to refer to the European Union and US/USA to refer to the United States; whenever the nouns Europe/America and the adjectives European/American are used, this is done to preserve the originality of a concept/quotation (for example, American exceptionalism or European integration).

2

Constructivists differ from rationalists in how they formulate questions about issues they examine (White, 2004, p. 23). Rationalists are more concerned with the why aspect – for instance, why particular foreign policy decisions were taken in the first place. Constructivists, on the other hand, are more interested in how these decisions were formulated. Similarly, Houghton (2006, p. 35) suggests that scholars adapting the constructivist approach to the study of foreign policy focus on the question “how possible”. Consequently, the focus of this study falls not on if and why human rights were present in foreign policy formulation, but how they were framed.

This work rests on constructivist-interpretivist philosophical foundations and, hence, on assumptions about the social construction of the world and knowledge and on the importance of intersubjectivity when analysing meanings and language. In this sense, human rights are a social construction as well. Their social construction was unfolding through debates about the existence and nature of rights and even their contestation. Rights were defined in opposition to slavery, torture, genocide but also in relation to democracy and freedom. Interpretation of processes, phenomena and meanings is an essential part of both inquiry and understanding of social constructions. This study follows closely this principle, as we interpret the meaning behind human rights, which emerges from a specific foreign policy of the US and the EU. Counter-piracy policies present an interesting case for discussion, because they refer to and involve human rights on several levels. We will talk about rights of piracy victims, rights of famine-stricken Somalis and rights of pirates.

1.1.2 Research Question, Foundational Assumptions and Main Argument

Based on these main propositions, we pose the following research question: How do the USA

and the EU conceptualise human rights and utilise the concept when formulating and implementing their counter-piracy policies? This question can be further spelt out in the

following way:

How are human rights conceptualised?

How are human rights intertwined with a particular role of each of the two actors?

How is this role reflected in the formulation and implementation of foreign policy?

What are the differences and similarities in the conceptualisation and utilisation of human rights between the EU and the USA in the framework of counter-piracy policy? Before presenting the main argument, we lay out several assumptions. The first assumption is that the constructivist approach is well suited to analyse the complexities of foreign policy in the

3

era of globalisation and increased international interdependence. In an international system marked by the production of a growing body of international norms and principles, it is important to think beyond the supremacy of national sovereignty and hard power. Constructivism provides the framework and the tools to do that.

Second, we assume that human rights are a constantly evolving and increasingly influential concept, which has an effect on the formulation and implementation of foreign policy. Although not as evident as in the case of democratic states (which often identify themselves as guardians of rights) this is true also for non-democracies. Even they abide by human rights norms, at least partially. Their compliance might amount only to not committing human rights violations. However, even this ‘minimalistic’ compliance signifies that non-democracies could succumb to international pressure. The importance of human rights is reflected in our research question as well. We investigate the essence of the human rights’ presence, instead of proving their influence.

The third assumption is that political bodies’ actions and inactions reflect their political identity. It is possible to discern political identity by looking at acts and speeches of political leaders, at internal political debates. Political identity is further reflected in citizens’ reactions towards domestic and foreign policies (for example, opinion polls, protests and mass demonstrations with powerful messages of support or opposition). Here, we centre on political identity as a national role conception or a set of roles that a political actor adopts to participate in international affairs. Consequently, the last assumption is that political identity is largely constructed on the basis of a rich mixture of political values. In most cases, these are codified into legal norms; they are influenced by historical and social circumstances and by a vision (usually shared by the majority of the political elite and the citizens) of the current and future role of the political body.

The main argument here is that human rights have been present in the formulation and implementation of foreign policy, and more specifically, counter-piracy policy of both the actors considered. However, there are some differences in the way human rights have been defined, articulated and utilised as a concept. This depends on the different prioritisation and interpretation of the underlying political values and the international roles the actors have envisaged for themselves. These differences should be sought in predominant philosophical ideas, legal traditions and historical and social contexts. Discourse serves as a trustworthy depository for this meaning construction. Thus, discourse is a useful subject of study and analysis.

4

1.2 Units of Analysis and Case Study

1.2.1 The EU and the US – a Needed Comparison

We selected the EU and the US as units of analysis because they are prominent international players. Furthermore, they both have been staunch supporters of the idea of human rights and their universal protection. Nevertheless, their foreign policy has been often criticised. Through the years, the US has been accused of leading aggressive, hegemonic policies, neglecting traditions and opinions of other states and societies. Both actors have faced accusations of double standards. In addition, the EU has been criticised for a hesitant foreign policy or a complete lack thereof. Despite their leadership positions in global political and economic affairs, the ability of both actors to adapt to new circumstances is constantly tested. The two world wars, the Cold War, the decolonisation, the rise of new, bold powers took the US and European countries out of their comfort zones. They were and still are forced to assume new and sometimes unwanted roles. Following World War I (WWI), USA had to ‘leave’ the isolation of its continent and become permanently committed to world affairs – its new roles included

arch-nemesis of the USSR, saviour of Europe, a world policeman and sole hegemon. These new roles

ushered in increased risks (of terrorism, for example), as well as a tendency to fear the US, but at the same time expect its intervention and assistance. The multiplicity of functions USA has appropriated during the years makes it an interesting unit of observation and analysis.

The European integration was also a reaction to events that upset the continent in the mid-20th c. It also reflected the need for the EU to find its place in the new world. From members of a formidable concert of empires that decided world’s fate, European states became aggressors, US

dependents, continental and significantly weakened republics. The European integration process

is a unique model for long-time enemies that relinquish a lot trying to achieve more. Only time will tell if the EU model could be replicated anywhere else or it was an inimitable combination of political will, crafty engineering, a stressful international environment and particular social and historical circumstances. The extent to which it is a successful model also remains to be determined.

The question of making and implementing foreign and security policy is one of the things that make a comparison between the two actors compelling and interesting. The fact that the EU does not have a foreign policy in the traditional sense of this word – the reason being it is not a nation-state – does not mean that it has none. In fact, one of the most successful initiatives of the EU has been exactly the counter-piracy operation ATALANTA. Another important point to

5

make is that the traditional style of foreign policy-making of the US does not automatically make its analysis easier. Internal divisions run deep in the US, as evidence by the 2016 presidential elections. The divisions on foreign policy issues influence the prioritisation of political values and national interests. The US is good example of a country where the role and impact of informal circles of experts, academics and lobbyists on both domestic and foreign policies is tremendous. Many have suggested that the War on Terror was planned not by President Bush but a group of neoconservatives led by Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz (Corscadden, 2014). Furthermore, it was argued that due to strict constitutional checks and balances, “Compared to every other liberal democracy, the U.S. conducts foreign policy in a cumbersome way” (Foreign Policy Association, n.d.). The foreign policy-making processes in the US and the EU are different but complex enough to be comparable.

Another motivation behind the choice of actors comes from role theory. Rikard Bengtsson and Ole Elgström (2011, p. 113) describe the US as the Europe’s most significant other. According to role theory, significant others are very important for understanding role-related processes. This means that EU’s self-definition of its place in world affairs is shaped at least partly in relation to the US. More importantly, we should not assume that since the two actors are collectively described as the West, they converge at all times and on all matters. Political scientists have been looking for possible points of transatlantic divergence, exemplified by the now seminal works about soft vs. hard power, Venus vs. Mars, normative vs. strategic power (Kagan, 2004; Laidi, 2008).

A third and very much related reason for the choice of actors is the concept of human rights itself. EU and US approaches to international documents on human rights has been anything but similar. While the EU became the first polity different from a nation-state to ratify an international treaty,2 the US has not ratified major international human rights documents. The two actors also diverge on a number of human rights-related issues, the most famous and contentious probably being capital punishment. The US also allows for a greater freedom of expression, while in EU Member States the criteria for a statement to qualify as hate speech appear stricter.

A point of disagreement between the two allies has been the International Criminal Court (ICC), often quoted as an example of the clash between US unilateralism and EU’s preference for multilateral solutions. The existence of ICC also tests the idea for international justice. The US is

2

The treaty in question is the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities. For the EU, the Convention entered into force on 22 January 2011.

6

opposing initiatives that might subject its military abroad to court proceedings anywhere else than in a US court. The ICC is relevant also to our case-study, due to the calls for establishing an international tribunal dealing with piracy. For a long time the predominant narrative of human rights has been centring on the differences between the East and the West. We consider a fruitful and needed exercise to see how the concept fluctuates within what we see as ‘the West’.

1.2.2 Somali Piracy as a Case Study

We chose to look at EU and US counter-piracy policies because of the faceted and level problems brought by piracy’s reappearance. These call for perspective and multi-lateral solutions. Piracy and the fight against it go far back in human history. In previous centuries, piracy was criminalised mainly because it harmed international trade. Nowadays it is also notorious for human loss and hostage-taking and, as the case of Somalia showed, for the obstructions it creates for humanitarian operations. Pirate hijackings in Somali waters date back to at least 2005 and ever since, they have had a negative impact on both international and local trade and economy and humanitarian relief. In fact, Somali piracy was called “singular for its scale, geographic scope, and violence...” (The World Bank, n.d.). The attacks near Somalia reached their peak in the period 2008 – 2011. Since then, they continue on a much smaller scale. We single out three main reasons why Somali piracy is an important and challenging topic. First, our study benefits from the quickly developing field of piracy studies. Christian Bueger (2013, p. 3) argues that the field is “inter-disciplinary…with an increased cross-fertilization between disciplines, spurred by the motivation of understanding the problem holistically”.3 The emergence of piracy studies allows for a fresh look at the specificities of contemporary piracy and its separation from security, terrorism studies, criminology and even historical studies. Piracy studies incorporate a wide range of perspectives to examine piracy and its effect on human existence, regional development and international cooperation. The interdisciplinary and holistic orientation of piracy studies allows the inclusion in related discussions of international intervention or human rights components. There are two ways to look at the human rights according to our research interest. First, we could look at how piracy violates basic rights, which in turn necessitates a reaction from local, regional and international actors. Another perspective is to examine how human rights (rights of both victims and captured pirates) are incorporated in strategies and policies.

3

In the same article, Christian Bueger notes that the term “piracy studies” was coined recently (in 2003) by Derek Johnson and Erika Pladet.

7

Therefore, the magnitude of the human rights dimension is the second main reason for choosing Somali piracy as a case study. We have to start with the human cost of pirate activities. It is reported that hostages go through ill-treatment and various abuse; for example, hostages have been used as a human shield during rescue operations or fights between rival pirate groups (Oceans Beyond Piracy, 2012, pp. 7-8). There are suggestions that sometimes the treatment of hostages by pirates amounts to torture (Ibid., p. 19).

Another direction for examining the human rights component is the way Somali piracy affects the broader region. There, the great poverty has been exacerbated by piracy which “disproportionately affects low-income countries” (The World Bank, n.d., p. 21). Besides affecting economic activities of all types like tourism and fishing, piracy also obstructs the delivery of much needed humanitarian aid. The latter alone could be seen as a human rights violation as the denial of humanitarian assistance could be seen as a crime against humanity under international law (Schwendimann, 2011, p. 1005).

The political instability and the absence of rule of law in Somalia have turned it into a ‘failed state’. Lawlessness, impunity and absence of a stable legitimate government are preconditions for an environment where organised crime, terrorism and piracy thrive. Thus, piracy off the Somali cost enters the vicious circle that has been dominating Somali history for decades. On one hand, it breeds instability, crime and human suffering. On the other, it is fuelled by the inability of the local government to cope with poverty, a key reason behind pirate activities. The reports of the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council connect piracy to both “chaos and deprivations in Somalia” (Bari, 2009, p. 20) and the “related human trafficking and terrorism” (Bari, 2010, p. 24).

Last but not least, we should look at the human rights component from the perspective of rights of pirates. This is not an unusual perspective for exploration. Possible violations of the rights of detained suspected terrorists are still widely discussed in relation to the US. Nowadays, the concept of human rights accommodates the idea that engaging in criminal activity does not deprive an individual of one’s rights. Three types of justification stand out: a moral/philosophical, a legal one and a political one. We believe the first one is best expressed in an argument against capital punishment in the US that “the refusal to execute also teaches a lesson about the wrongfulness of murder” (Pojman and Reiman, 1998, p. 106). In this sense, a political actor cannot claim to be guided by concern for human rights in the world, if it does not follow human rights standards. This is related to the political side of the argument, namely that such double standards could backfire. First, failure of actors to protect human rights could

8

damage their international standing and question the image they project. Second, inability or unwillingness to uphold human rights could exacerbate the problem which the actor is fighting by breeding radicalisation and retaliation. The legal argument rests on already established legal practice. In a famous judgment, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ordered France to pay compensation to Somali pirates due to infringement of their right to liberty and security (BBC News, 2014). The protection of human rights of pirates thus becomes a necessary element of initiatives to combat them. This was expressly stated in a UN Security Council Resolution 2184 (2014), which “calls upon Member States to assist Somalia,…, to strengthen maritime capacity in Somalia, including regional authorities and, stresses that any measures undertaken pursuant to this paragraph shall be consistent with applicable international law, in particular international human rights law”.

This brings us to the third reason that makes the case of Somali piracy interesting. As underlined above, the phenomenon has been generating significant international uproar and calls for international cooperation. This comes in line with important issues like the question of responsibility of world states towards states or peoples struck by tragedies. Thus, it is related to the more general question of how and when states cooperate and engage in international intervention.

The foundations of the legal framework defining piracy and the measures to fight it are provided by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Art. 100 of UNCLOS states: “All States shall cooperate to the fullest possible extent in the repression of piracy on the high seas or in any other place outside the jurisdiction of any State” (UN General Assembly, 1982). It is noteworthy that this article is formulated as the duty to suppress piracy that countries bear. The next few UNCLOS articles provide a definition of piracy and outline the range of actions that states are entitled and required to take if they come across pirate vessels. The legal framework provided by UNCLOS is mentioned in Resolution 1618/2008 of the UN Security Council, which under Chapter VII of the UN Charter authorizes anti-piracy operations by encouraging states to “increase and coordinate their efforts to deter acts of piracy and armed robbery at sea…” near Somalia (UN Security Council, 2008a). Subsequent related UN Security Council Resolutions also refer the fight against piracy to the broader efforts to bring peace and stability to Somalia within the mission AMISOM, run by the African Union with the approval and support of the Security Council. In the least years, there have been more than ten UN Security

9

Council Resolutions4 dealing specifically with piracy (in addition to those centring on Somalia in general).

Resolution 2184 (2014) recognises the importance of one counter-piracy initiative, namely the Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia (CGPCS), formed in 2009. CGPCS is unique in the way it applies “informal governance” by creating a forum where various stakeholders harmonise their activities in order to achieve the best response to piracy (Lessons from Piracy, n.d.). Furthermore, a Consortium of research institutions initiated the Lessons Learned Project to identify best practices stemming from the work of CGPCS (Ibid.). The reference to the CGPCS here is important for two reasons. First, the Contact Group might be considered a good example of an existing epistemic community that tries to modify the status quo by harmonising anti-piracy efforts and building a new model for cooperation. The CGPCS is also important because in 2013 and 2014 it was chaired respectively by the US and the EU. Thus, it provided an excellent opportunity for the two actors to lead and channel large-scale international anti-piracy activities. It is within this conceptual, legal and political environment that the US and the EU answered the calls of the Security Council to deter piracy off the coast of Somalia. The time frame of our study starts in 2008, with the adoption of a key resolution, namely UN Security Council resolution 1851 (2008b). It authorises states cooperating with the Somali Transitional Federal Government to extend counter-piracy efforts to include potential operations in Somali territorial land and airspace, to suppress acts of piracy and armed robbery at sea. The time frame continues until the end of 2016 and encompasses major EU and US anti-piracy efforts. We focus not only on military/crisis management aspects of anti-piracy initiatives, but on the entire strategies of the two actors. Therefore, we look also at non-military policies related to prosecution of captured pirates and to efforts to alleviate the effect of piracy in the region. Detailed presentations of EU and US policies, mandates, strategies and the overarching frameworks of human rights protection within which they are elaborated are provided in chapters 3 and 4 respectively.

1.3 Constructivist Research Framework

1.3.1. The Constructivist Research Programme

The ontological and epistemological principles that guide researchers influence their selection of methodology and methods, because they form the “philosophical basis of a research project”

4

For a list and full texts of all UN Security Council Resolutions on Somalia, please see UN Documents for Somalia: Security Council Resolutions (link provided in the List of References).

10

(Hesse-Biber and Leavy, n.d., p. 4). This research falls within the qualitative research paradigm and its core objective is to uncover the creation of meanings of concepts. Therefore, we do not seek a causal explanation; we do not intend to provide a causal link between the concept of human rights and foreign policy. Instead, we look at how the concept of human rights is integrated in foreign policy formulation and interpreted to explain, support or justify foreign policy decisions.

One of the ‘faces’ of realism and Realpolitik in the 20th c. is the Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. His words “In the end, peace can be achieved only by hegemony or by balance of power” (in Krauthammer, The Washington Post, 2014) are much quoted. Therefore, the suggestion of some analysts that in a recent book, “World Order” Kissinger made a constructivist turn (Lynch, 2014) came as a surprise. In the book, Kissinger reflects on the importance of history, identity, culture and norms for the behaviour of states. He does not forget values – power politics are not the only factor contributing to the preservation of international stability, the latter also requires adjusting the different value systems floating around us (Fiott, 2014). Notwithstanding the fact we are all human beings, we do not share the same values or if we do, we prioritise them in a different way.

According to constructivists, politics is heavily influenced by norms, ideas, values and the social constructions they create in specific cultural and historical environments (Finnemore and Sikkink, 2001; Reus-Smith, 2005; Lynch & Klotz 2007; Price, 2008). Constructivists are also interested in communication, language and speech acts as tools to disseminate values and principles and project influence. Thus, constructivism creates a fruitful ground for observing formation and transformation of identity and foreign policy. As we see below, constructivism not only does offer a viable alternative to the more traditional (neo)realism and (neo)liberalism. It also stimulates borrowings from different disciplines in the process of analysis, thus contributing to the development of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches.

We are persuaded that constructivism is particularly suitable for our research goals. By studying the international behaviour of actors, it is a useful framework for analysing US and EU foreign policy actions. Constructivism also provides a useful vocabulary and a well-developed set of propositions to explore meaning, meaning construction and concept interpretation.

Our study refers to the broader discussion about sources of knowledge, processes and techniques for acquiring knowledge and the way knowledge relates to ascribed meanings. There is a general agreement that constructivism is not so much a theory of IR as an approach to their analysis. Emanuel Adler identifies four types of constructivism – modernist, modernist linguistic,

11

radical and critical – which despite their differences “converge on an ontology that depicts the social world as intersubjectively and collectively meaningful structures and processes” (Adler, 2002, p. 100). The foundations of that ontology are: the variety of intersubjective perceptions that enrich the world around us; the existence of social facts as such only due to human agreement; the constant reference on the meanings and knowledge we individually have to the collective ones expressed through norms and discourse (Ibid., pp. 101-103). If we look at human rights through the prism of relativist ontology, we see them as resulting from interaction and renegotiation of meaning. The concept has been shaped by debates about sources, nature and implications of rights. At the same time, the importance attached to rights results from references to other notions like democracy, liberty, happiness, dignity, often encountered in relevant discourse. This importance also stems from pitting human rights against significant counterparts – slavery, torture, genocide.

Moving to epistemology, Adler (Ibid., pp. 101-103) states that constructivists (except for the radical strand) agree that their interest in how things come to be (instead of how things are) leads to open-ended “contingent generalizations” that add up to the richness and unexpectedness of the social world. From a constructivist epistemological position, one would argue in favour of a multiplicity of constructed meanings, none of which is the only true one; this position informs the interpretivist theoretical perspective which allows for differing interpretations of reality and its constitutive elements (Gray, 2009, pp. 20-22). Symbolic interactionism – an example of interpretivism traced back to John Dewey and George Herbert Mead – is based on the notion that people act upon meanings that are likely to change as a result of their interaction with the surrounding phenomena (Ibid.). Guided by values, in their actions individuals do not blindly follow pre-determined meanings but reflect on meanings and often change them. Adopting constructivist presumptions in IR analysis allows for an innovative look on how states utilise existing meanings and create new ones in the course of history and communication with counterparts. Today, key concepts, like terrorism, ethnicity and sovereignty, still do not have a single agreed on definition. Instead, as these concepts are used, their meanings are expanded, narrowed, reaffirmed or amended. The same goes also for human rights – as a whole and as separate rights.

At the basis of this research lies the perception that the world in which both individual and collective actors exist, develop and act is a socially constructed one. The same is valid for the knowledge we acquire during our existence and the concepts we choose to exploit when we make decisions, embrace certain courses of action, while discarding others. Indeed, this work

12

accepts that values, norms, identities, interests and human rights themselves make better sense if looked at from a constructivist-interpretivist epistemological position.

Constructivism rose to prominence as an alternative to the (neo) realism and (neo) liberalism that have dominated the IR field for decades. We can discuss some of the differences between the three perspectives on IR by means of a reference to international human rights law (IHRL), namely by asking the question: Why would a powerful actor join a binding international human

rights treaty? According to realists, the interest-driven and power-seeking state will ratify such a

treaty only if it brings benefits in terms of power and interest fulfilment. The association of the treaty with certain relative gains will make it more attractive to the actor in question. On the contrary, if the actor does not envisage any benefit, it will not engage in that process. Its motives will always be based on principles like self-help, rational choice and preservation of sovereignty. Thus, a possible realist explanation of the USA’s refusal to join the ICC would be that it, as a global power, is unwilling to join an institution that essentially curtails its ability to pursue its national security interests. Similarly, the US could be tempted to ratify the treaty in case it presents new opportunities for furthering its foreign agenda, like providing new channels for international pressure or persuasion.

Liberalism and neo-liberalism share a more optimistic worldview. They endorse the creation and development of international institutions rooted in liberal values whose popularisation in turn stimulates cooperation between states that share them. Thus, liberalists and neoliberalists would explain an actor’s decision to join a human rights treaty with their belief that institutions are important to the well-being of states, since the treaty and the international body it creates are an institution in themselves. The treaty/institution then creates internal rules which both increase the cooperation between states and ‘distributes’ among them the profit from cooperation. The profit does not need to be of economic nature. It might as well include the popularisation of internal liberal policies or values, which will increase the predictability of external and internal behaviour.

Constructivists are more likely to pay attention to the ideas that motivated the decision to join the treaty rather than the immediate consequences of ratification. The decision might be driven by “principled beliefs” in the value of human dignity or in belonging to an international community as source of peace and cooperation (Tannenwald, 2005 in Jackson and Sorensen, 2013, pp. 213-214). Constructivists will also examine the discourse that accompanied decision-making because discourse is an important carrier of values. The review of the state-of-the-art constructivist scholarship brings forward its relentless interest in identity, values and norms.

13

Four main analytical areas of interest emerge: 1) the mutual constitution of structures and agents; 2) the relevance of social and historical context; 3) the influence of discourse and communication (epistemic communities); 4) the significance of values and identity for norm-formation and norm-compliant international behaviour. Below, we look at these thematic areas, always illustrating them through the notion of human rights.

1.3.2 Main Constructivist Premises

1.3.2.1 Mutual Constitution of Agents and Structures

The constant interaction between agents and structures is one of the pillars of constructivist analysis. According to Alexander Wendt (2003, p. 10), the agency attributable to states in international politics has two origins: the discourses of decision-makers about states’ responsibilities, interests, etc. and the fact that international law attributes to them legal personality. Structures are seen as “stocks of knowledge” or “distributions of ideas” (Ibid., p. 249). Following this, human rights could be viewed as a knowledge structure that is “continually constituted and reproduced by members of a community and their behaviour” (Adler, 1997, p. 326). The concept of human rights could be enriched or belittled because of the meaning that actors ascribe to it through speech acts and actions.

Agents and structures influence and modify each other when they interact. As Jeffrey Checkel (1998, p. 328) claims, “agents (states) and structures (global norms) are interacting; they are mutually constituted”. In order to grasp structural change, it is necessary to “identify agents in norm building and transmission” (O'Neill, Balsiger and VanDeveer, 2004, p. 163). This initial identification is important for analysis, because not all agents support all changes to the structure and in turn, not all structural changes influence all actors. Understanding the character of the agents driving the change affects the change’s potential and popularity. For example, if a relatively small number of small states attempt structural modification, it might influence the states in question but it is unlikely to have a broader repercussion. On the contrary, if a change is supported by a bigger number of more influential states, not only they but also the others are likely to be affected by it. In this case, the structure was modified significantly.

Let us return to our example of a treaty on human rights. The document and the international regime are themselves a structure calling for rights’ protection. But their essence and guiding principles are formulated and endorsed by actors, be they states, regional blocs or civil society organisations. If they do not uphold the treaty’s principles, it will be void of substance and legal force. At the same time, once strengthened, the structure starts to impact the behaviour of the

14

states that made its existence possible. Once the treaty is signed and ratified by the actor, the latter becomes bound to it and needs to harmonise its actions with the new document. The structure, in a way, commences a life of its own.

This is in line with the observation that “just as structures are constituted by the practice and self-understandings of agents, so the influence and interests of agents are constituted and explained by political and cultural structures” (Adler and Haas, 1992, p. 371). Mutual constitution of agents and structures does not occur randomly and by chance. Agents support and embrace changes that are coherent with behaviour they consider normal and pertinent to their self-image. Thus, it is unlikely that a state will voluntarily accept a structural element that goes contrary to its perceptions and practice. Simultaneously, perceptions and practice will be shaped by the structural element in question, because once strengthened, it will introduce a specific behavioural pattern.

1.3.2.2 The Relevance of the Social and the Historical

Making forecasts about the future on the basis of present circumstances is central to IR studies and FPA. But now ever more often, scholars turn their glance to the past trying to back their claims. It is known that when examining past events, we should not be biased by the circumstances of the present. At the same time, the resources of the past should be employed to investigate present developments, as actions and decisions could have historical explanation, equivalent or reference.

Constructivism is often credited with the return of international history to the study of IR. It intensified and stirred up the way historical analysis is done, by seeking to “re-read the historical record, to re-think what has long been treated as given in the study of international relations” (Reus-Smit, 2005, p. 207). Historical experience is closely connected to social peculiarities. Leading constructivist scholars acknowledge that the non-material factors they look at (ideas and norms) could be understood properly only through scrutinizing the historical and social environment in which they developed (Katzenstein, 1996; Reus-Smit, 2005; Hurd, 2008; Checkel and Katzenstein, 2009). Interests and identities as well should not be separated from historical and sociological analysis, as they do not exist outside them or in opposition to them. Instead, they are products of history and society. Furthermore, turbulent historical moments or society transformation might stimulate emergence and establishment of new norms (Finnemore and Sikkink, 1998, p. 909). An often-quoted example is that of Nazi atrocities during WWII, which

15

necessitated the definition of genocide and the adoption of measures to punish it and prevent its future occurrences.

Hedley Bull pointed out that “historical inquiry, along with philosophy and law” are crucial elements of the study of IR (in Reus-Smit, 2008, p. 396). The importance of historical inquiry for IR is so vivid that Christian Reus-Smit suggests that we might talk about a constructivist philosophy of history, whereby “there is no international ‘history,’ only ‘histories’” (Ibid., p. 401). Reminding the significance ascribed by E.H. Carr to the historian’s interpretation of facts and Skinner’s assertion that historians give facts “life and value”, Reus-Smit concludes that essentially “historians construct history” (Ibid., pp. 402-404). These suggestions are important for us in two ways. First, they imply that choosing different historical accounts when discussing a foreign policy decision might yield different analytical findings about actors’ motivations, intentions or influences. Second, we face a multitude of histories that, being rich in values, could help our search of the mark left by values. Ideas also occupy a particular place in the constructivist philosophy of history, as the centre of examination is not the “history of ideas” but “ideas in history” and their constitutive and meaning-ascribing powers (Ibid., p. 408). In our research, we investigate how human rights enter the decision-making process at a given historical moment. To do this, it is useful also to see if there are political and/or policy traditions that favoured one historical interpretation of the idea of human rights over another.

In this sense, any human rights treaty is also a historical episode, a social marker. It is difficult to imagine that the very important Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) could have been produced a century or two ago. Any previous historical period lacked circumstances such as the philosophical belief in human dignity or the idea that states do not ‘own’ their people. In the 20th c., torture of human beings is often defined as a practice that goes against civilisation itself – something reflected in the related terms inhumane, cruel and degrading. In contrast, through most of recorded history, torture was not only practiced publicly, but considered normal.

Let us now use the example of the human rights treaty to consider the importance of the social context. The anti-torture norm would not ‘stick’ were it not internalised by the societies of the majority of states. The persistence of the norm suggests that societies endorse values embodied in this norm, like the belief in the inviolability of the human body, originating in human dignity. The international aspect of norm acceptance consists in pressure and sanctions states and international organisations can now exert on states that practice torture. Unfortunately, torture is still practiced today, but it has moved away from public squares to

16

secret prisons. The secrecy of the practice does not change the fact that it exists, but it is a sign that its perpetrators realise it is wrong, immoral and/or illegal. Torture is not ‘normal’ in our world today and states are well aware of that.

1.3.2.3 Communication Matters

While the processes of shaping of identities, formulation of interests and adoption of norms need a specific context, they also do not happen by chance within this context. As Thomas Risse-Kappen (1994) perfectly explains “ideas do not float freely” but are caught, appropriated and passed forward by agents who share them. A major premise of constructivism is the belief in the social nature of actors, who make their inherent values known. Special attention is paid to the communicative processes through which international actors ponder on their priorities, options and moral codes (Wendt 1992; Adler, 1997; Reus-Smit, 2001). They can do that directly – by declaring that an action is grounded in an existing value. Alternatively, when pursuing their interests, actors could undertake a series of actions that demonstrate consistent support for a value, norm or a practice. Communication can explain an action after the action has occurred, by referring to international norms (Katzenstein, 1996; Boekle, Rittberger and Wagner, 1999; Finnemore and Sikkink, 2001; Reus-Smit, 2005).

The constructivist thematic area where the importance of discourse is most clearly visible concerns epistemic communities (Adler and Haas, 1992; Risse-Kappen, 1994; Adler 2005). It has been hypothesised that their formation and activities rest on two pillars: their shared “set of normative and principled beliefs” and their ability to interact and influence policy (Haas, 1992 in Boekle, Rittberger and Wagner, 1999). The success of their efforts to push for a particular policy relies on their independence, the high level of their expertise, the number of their communication channels and persuasion abilities. As Adler and Haas (1992, p. 389) stress, “[e]pistemic communities influence policymakers through communicative action […] the negotiations of meanings, understandings, and beliefs are intertwined with the negotiations of actions at every step along the way”. On a domestic level, epistemic communities are often formed by experts working in the civil society sector, who periodically publish policy briefs indicating a desired policy. It depends on their skills to persuade decision-makers to choose a policy among all the alternatives. Internationally, the interplay between local, regional and global epistemic communities is even more dynamic and influential. Epistemic communities have to build domestic coalitions, as the ability to do that depends on the “nature of […] political institutions” and the “values and norms embedded in […] political culture” (Risse-Kappen, 1994,

17

p. 187). Thus, epistemic communities emerge as a serious agent; through their webs they invoke structural changes, which other agents have to comply with. Above, we identified human rights as a structure in itself. Consequently, the constellation of actors that reflect upon and utilise human rights constitutes the epistemic community that drives the development of the concept over time.

1.3.2.4 The Importance of Values

The popularisation of new ‘rules of the game’ was discussed by Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink (2001, p. 400) in their influential research on norm entrepreneurs. These push for the creation of new norms or elimination of existing ones that contradict their preferences and beliefs. Norm entrepreneurs may not personally benefit from a norm emergence, but they nevertheless support it because they “believe in the ideals and values embodied in the norm” (Finnemore and Sikkink, 1998, p. 898). After a process of development and appropriation, norms begin moulding actors’ interests and identities and constitute what some constructivists call ‘culture’ (Reus-Smit, 2005, p. 210). Culture has been defined as an aggregate of “evaluative standards, such as norms or values, and […] cognitive standards, such as rules or models defining what entities and actors exist in a system and how they operate and interrelate” (Jepperson, Wendt and Katzenstein in Katzenstein, 1996, p. 56). The culture of the actors makes their self-identification and self-definition easier.

Friedrich Kratochwil (1989, p. 64) describes values as working on the level of “emotional attachments” that affect not the actions of actors, but their attitudes, which often includes “overcoming the “weakness of the will”. The intangibility of values forces those who study them to concentrate on the level of perceptions rather than on concrete actions with tangible consequences. It is a task of the constructivist approach to bring perceptions and actions closer. One step is to examine if and how agents base their actions on a set of values. This matters because a value-set ultimately affects how actors perceive structures with which they interact.

Constructivist interest in values goes hand in hand with the significance attributed to normative and ideational structures that influence through “imagination, communication and constraint” (Reus-Smit, 2005, p. 198). The same three mechanisms can be applied to our examination of values. Values channel the flow of imagination and, consequently, the direction of actions. This is linked to the function of constraint. Values place limitations on behaviour, thus making it easier for actors to choose their line of conduct. Finally, actors try to communicate their values to others – be it directly or indirectly, consciously or unconsciously. Below, the link

18

between values and norms will be further elaborated by reference to IL, increasingly studied by constructivist scholars of IR.

1.4 Values, Norms and Interests

1.4.1 Values

The major obstacle encountered by a researcher who analyses the influence of values is their abstractness. Our values are questioned by others exactly because proving their direct influence on our actions is difficult. We are free to profess a set of values that guides our behaviour but at the end it is up to others to decide whether our actions are coherent with this set. This observation is valid for international actors as well. For the first Bush administration, the 2003 Iraq War was a necessary step of the fight against the ‘Axis of Evil’, while other states saw it as an act of aggression. Value-laden language is often part of the speeches of political leaders. As a consequence, they might encounter two types of difficulties. First, leaders often have to explain how a position or an act is consistent with their values. Second, as good as their explanation might be, it is always subject to interpretation by their audiences. This takes us back to the above-mentioned importance of context.

In order to understand the significance of values for IR, we look at both their philosophical foundations and attempts for empirical measurement. A philosophical perspective allows us to understand what is generally meant when we talk about values. Any empirical ranking of values could help us identify those with greater influence. For example, if democracy is a state’s most distinguished value, it is unlikely that it will not be mentioned in speeches of political leaders.

A definition of individual values states that they are “a relatively small number of core ideas or cognitions present in every society about desirable end-states of existence and desirable modes of behaviour instrumental to their attainment that are capable of being organized to form different priorities” (Rokeach, 1979 in Adler, 2005, p. 271). One part of the definition is very important for both interpersonal communication and interstate relations. Values themselves are not different – their prioritisation is. We might hypothesise that some people are more inclined to tell a lie than hurt a friend. For them, the value of friendship overrides the value of telling the truth. Similarly, an international actor might choose to follow international law (IL) rather than support an ally whose action contradicts it. In this case, we should take into account also international and domestic circumstances, as well as other factors that may have influenced this decision. We should consider the action’s consequences and the stakes involved. If the

19

stakes are high and the consequences the actor faces for going against its ally are negative, this might mean that actor prioritises immaterial principles over material consequences.

Of course, constructivism is not the only approach to IR that considers values. Realism and liberalism also do that, the latter claiming that some international actors aim at spreading liberal values. The inherent rationalist and materialist features of the two theories make values, norms and social interaction matter little as constitutive elements on the international scene (Reus-Smit, 2005, p. 197). What distinguishes constructivism is the view that values are an important part of the normative and ideational structures – although non-material, “values also have structural characteristics” (Ibid.). Another clarification to make here is that constructivism does not deny the importance of material factors, but places them on an equal footing with ideational ones.

Essentially, they are sources of knowledge in the structure, which, following Wendt’s definition is a main distributor of ideas. The fusion of values, knowledge, beliefs and expectations allows judgment of past, present and future events and behaviour (Adler, 2005). Some constructivists argue that the appearance of an international community or even collective identity comes as a result of the transnational spread of specific values or the simultaneous transformation of others (Wendt, 1994; Adler, 2005). These processes would involve the active participation of epistemic communities or the transnational advocacy networks that begin working on an issue, because they share both expertise and values (Risse, Ropp and Sikkink, 1999, p. 18). Values are not static but are constantly on the move in the international environment, carried by the words and ideas of actors.

Like interests, values are not given. They are formed as a result of problems faced by actors in the international scene and this guarantees their constant interaction with facts and interests (Adler, 2005). When researching on values, one cannot avoid the question of measurement. This is important, because empirical findings help understand how an actor prioritises among values. Eurobarometer (77, Spring 2012) studies identify human rights as a value in itself, a view adopted also in the present work. We should, however, consider that human rights are accompanied by other values like peace, democracy, justice. These values carry so much charge in terms of knowledge and beliefs that they allow us to employ them in various ways. Our analysis has chosen human rights as the lead value and others as ‘secondary’ or supporting values. But this is not a rule – liberty or democracy might also be looked at as leading values, while human rights as their auxiliaries. Empirical studies are useful because their different methodologies help us find a way in the complex and dynamic space of values.

20

Values are solid building blocks in the non-material structures examined by constructivists. A similarly important block is international norms. Here, they are presented not only as stand-alone factors behind actors’ behaviour but also in their connection to values. IL norms can be viewed as the more ‘material’ manifestation of values. Below we show how shared and deeply embedded values can be translated into words and start limiting states in their behaviour.

1.4.2 Norms

Finnemore and Sikkink (1998, p. 891) define norms as standard of “appropriate behaviour with a given identity”. This definition introduces the notion of appropriateness, which can be linked to values. Political actors judge the appropriateness of an action by weighing the non-material and principled implications of their actions. These implications are informed by a set of prioritised values. The second significant element in the definition of norms is the reference to identity. The self-understanding of the actor has a key contribution to the actor’s perception of appropriateness. What a political entity values in a domestic and an internationally plan, affects its judgments and decisions.

A definition of norms states that international norms are “those expectations of appropriate behaviour which are shared within international society or within a particular subsystem of international society by states, its constituent entities” (Boekle, Rittberger and Wagner, 1999, p. 14). Norms support a structure in its own right that guides and limits actors’ options. The concept of human rights is a serious source of international legal norms. Thus, it is a good example of how norms create a frame of action. The appearance of new norms is conditioned upon suggestions and adoption by the states. In this sense, actors change the frame – the agents have influenced the structure. At the same time, since the frame poses limits to the states’ actions, it manages to influence them, as they are judged by their actions, by the roles they project. However, we have to keep in mind that the structure of international human rights norms does not have only a limiting function. It can also open new opportunities before actors. For instance, the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine provides justification and instruments for intervention in case of a state’s aggression towards its own citizens. This is related to another observation about the functions of norms – the frame demarcates the boundaries, within which it is ‘safe’ to act.

While in the past the actions of states were often criticised as violent or unjust, today the world ‘illegitimate’ is increasingly used in political discourse. Agents follow the norms because they see them as legitimate and realise the importance of legitimising their actions (Florini, 1996,