UNIVERSITY OF PISA

DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHIATRY, NEUROBIOLOGY, PHARMACOLOGY AND BIOTECHNOLOGIES (MED-25)

RESEARCH DOCTORATE IN NEUROBIOLOGY AND CLINIC OF

AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

THESIS

Relationship between adult separation anxiety

disorder and complicated grief in a cohort of 454

outpatients with mood and anxiety disorders

CANDIDATE

SUPERVISING PROFESSOR

Matteo Muti

Prof. Stefano Pini

President: Prof. Antonio Lucacchini

Abstract

Background

Recent epidemiological studies indicate that separation anxiety disorder occurs more frequently in adults than children. Data from literature suggest that adult separation anxiety disorder (ASAD) may develop after a bereavement or threat of loss. Research has demonstrated that bereaved persons may present a clinically significant grief reaction, defined as complicated grief (CG) that causes a severe impairment in quality of life.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between ASAD and CG in a large cohort of outpatients with mood and anxiety disorders.

Methods

Study participants comprised 454 adult psychiatric outpatients with DSM-IV mood or anxiety disorders diagnoses. All subjects were assessed with the structured clinical interview for diagnostic and statistical manual (IV edition) axis I disorders to establish DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis and psychiatric comorbidity.

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Young Mania Rating Scale were used to assess severity of depression and mania, respectively. Anxiety and panic symptoms were assessed by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale and the Panic Disorder Severity Scale.

Adult Separation anxietydisorder was assessed using an adapted version of the Structured Clinical Interview for Separation Anxiety Symptoms. Complicated grief symptoms were assessed by the Inventory of Complicated Grief. Social and work impairments were evaluated using the Sheehan Disability Scale.

Results

The overall frequency of ASAD in our sample was 43% and frequency of CG was 23%. CG resulted specifically associatedwith ASAD (p=.002) ) and not with childhood separation anxiety disorder neither with any other DSM-IV-TR disorder.

The presence of CG influenced various clinical features of subjects with ASAD; particularly CG determined more severe mania (p=.011) and depressive symptoms (p=.014). Furthermore subjects with ASAD and CG endorsed higher level offunctionalimpairment than those with only one of these conditions.

Finally in bipolar patients CG was associated with more severe mania (p=.026), depressive (p=.004) and anxiety (p=.005) symptoms and with a more severe

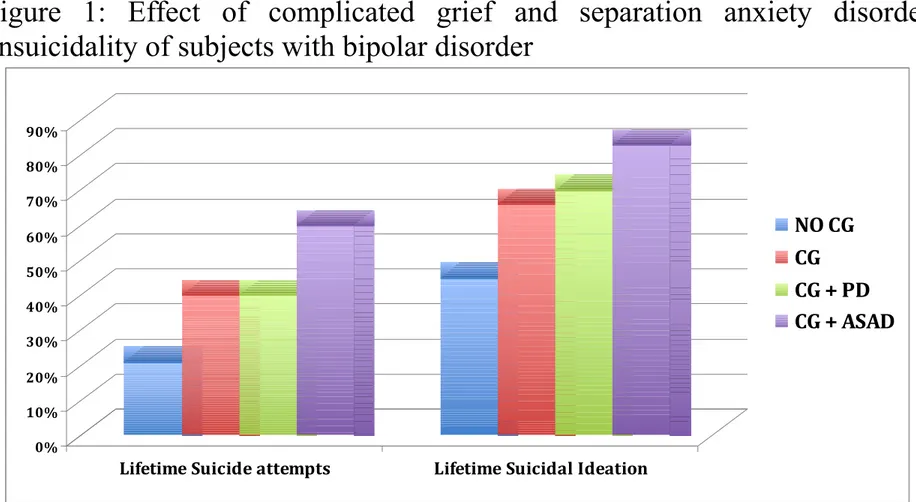

lifetime bipolar symptomatology (MOOD total score: p=.000; MOOD depressive tot score: p=.000, MOOD mania tot score: p=000). Bipolar subjects with CG reported higher level of lifetime suicidal ideation (p=.027) and an higher number of suicide attempts (p=.027) than bipolar subjects without CG. In addition co-occurrence of CG and ASAD comprised a sub-population of bipolar patients at vey high risk of suicidality (60% CG with ASAD vs 40% CG without ASAD vs 40% CG with panic disorder vs 20% no CG).

Conclusions

We found that in our sample of psychiatric outpatients with mood and anxiety disorders, complicated grief is specifically associated with adult separation anxiety disorder. Co-occurrence of these two conditions was associated with high levels of functional impairment.

Furthermore in bipolar subjects, CG determinesaworsening in the symptomatology of both bipolar and comorbidity anxiety disorder; CG results associated with separation anxiety symptoms and with an high frequency of panic attacks but not with panic disorder suggesting that in bipolar subjects with CG,panic attacks could be secondary to ASAD and not correlated with a primary panic disorder.

Finally in bipolar subjects the presence of CG determines a more severe lifetime bipolar symptomatology and causes higher risk of suicidality, expecially if ASAD is in comorbidity with thoses diagnosis.

Further studies are warranted to investigate in more detail possible mediating factors in the putative relationship between ASAD, CG and other mood and anxiety disorders.

INDEX

ABSTRACT ...2

1. INTRODUCTION …...7

1.1 Separation Anxiety Disorder...7

1.2 Complicated Grief …...11

1.3 Relationshio between Separation anxiety and complicated grief...15

2. SPERIMENTAL STUDY...16

2.1 Aim of the Study...16

2.2 Methods...16 2.3 Statistical Analyses...22 2.4 Results...23 3. DISCUSSION...28 4. REFERENCES...33 5. TABLES...41

1. Introduction

1.1 Separation Anxiety Disorder

Childhood Separation anxiety disorder (CSAD) is a well-established diagnostic category in the diagnostic and statistical manual fourth edition-text revision (DSM-IV-TR). By contrast, little attention has been paid to the occurrence of separation anxiety in adulthood (ASAD).

The DSM-IV-TR defines CSAD using 8 criterion symptoms related to excessive anxiety concerning separation, actual or imagined from home or from those to whom the person is attached. The disturbance must last for a period of at least 4 weeks, and cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, academicor other important areas of functioning. The DSM-IV-TR acknowledges the possibility that separation anxiety may persist into adulthood, but, until recently, manifestations of separation anxiety in adulthood are left ambiguous and the frequency with which it occurs is not well established.

In a series of articles published at the end of nineties, a group of Australian authors advanced the hypothesis that separation anxiety disorder could occur in adulthood as a discrete entity characterized by a constellation of anxiety symptoms including extreme anxiety and fear about separations, actual or

imaginative, from major attachment people, avoidance of being alone and fears that harm will befall those close to them (Manicavasagar et al., 1997; Manicavasagar and Silove, 1997, Wijeratne et al., 2003).

Recent epidemiological data show that separation anxiety disorder may occur during adulthood with a lifetime prevalence in the general population of 6.6% (Shear et al. 2006). In the Shear's et al. study, approximately one-third of the respondents who were classified as childhood cases (36.1%) had an illness that persisted into adulthood, although the majority classified as adult cases (77.5%) hadthe onset of the disorder in adulthood. Life-time child and adult separation anxiety disorders were significantly more common among women than men.

Adult separation anxiety disorder in the national comorbidity survey-revised (NCS-R) was comorbid with other DSM-IV disorders and was a seriously impairing condition in the domains of social and personal life in about 50% of the comorbid cases and 25% of the pure cases. The majority of people with estimated adult separation anxiety disorder were untreated, even though many obtained treatment for comorbid conditions. These results suggest that treatment providers often fail to recognize separation anxiety disorder in the context of other comorbid conditions.

Data on relationships of separation anxiety symptoms with other adult anxiety or mood disorders are sparse in the literature. One hypothesis that persisted in the literature is that early separation anxiety is specifically linked to risk of panic disorder in adulthood (Klein DF, 1980). Indeed, with a few exceptions, the majority of earlier retrospective studies tended to support such a hypothesis (Yeragani et al., 1989; Silove et al., 1995; Pine et al., 1998).

Some authors supported the hypothesis that early separation anxiety operates as a general vulnerability factor, increasing the risk of various anxiety and mood disorders in adulthood (Lewinsohn et al., 1997). Some studies found approximately equal rates of a childhood history of separation anxiety disorder in patients with social phobia or panic disorder, providing evidence against a unique relationship between separation anxiety disorder and panic disorder (Otto et al., 2001).

Some recent clinical studies confirmed that ASAD is frequently comorbid with mood and anxiety disorders in clinical settings (Manicavasagar et al., 2000; Wijeratne and Manicavasagar, 2003; Pini et al., 2009; Cyranowski et al., 2002). Pini et al. found a strong correlation between adult separation anxiety and a history of separation anxiety during childhood among bipolar patients than in other affective disorders. They also found that adult separation anxiety was predictive of an earlier age at onset of bipolar disorder(Pini et al., 2005).

The DSM IV-TR suggests that separation anxiety may develop after a real or threatened loss (e.g., illness or death of a child relative or pet).Furthermore Australian researches describe a series of clinical cases that reported the onset of separation anxiety disorder following loss suggesting a direct relationship between separation anxiety disorder and grief reaction (Manicavasagar et al., 1997; Manicavasagar and Silove, 1997).

1.2 Complicated Grief

The death of a loved one is one of the most distressing life events that greatly affects physical, social and psychological well-being. There is agreement in literature that bereavement is associated to an excess morbidity and mortality (Latham et al., 2004) and may trigger an increased risk for major depression and anxiety disorder.

Many studies have been recently focused on the distinction between normal and complicated grief.In a series of articles published at the end of nineties investigators have identified a clinically significant grief reaction, currently referred to as Complicated Grief (CG) that occurs in about 10%-20% of bereaved people and results from the failure to transition from acute to integrated grief

(Middleton et al., 1996).Although CG is not yet a formal psychiatric diagnosis, there is a growing consensus about its core elements which include unrelenting grief persisting 6 or more months after the loss, with symptoms of separation distress (recurrent pangs of painful emotions, with intense yearning and longing for the deceased, and preoccupation with thoughts of the loved one) and traumatic distress (sense of disbelief regarding the death, anger and bitterness, distressing, intrusive thoughts related to the death, and pronounced avoidance of reminders of the painful loss)(Shear and Shair, 2005). Characteristically,

individuals experiencing complicated grief have difficulty accepting the death, and the intense separation and traumatic distress may last well beyond six months,perhaps indefinitely (Engel, 1961; Zisook et al., 1994; Auster et al., 2008;Bonanno and Kaltman, 2001).

CG is associated with significant distress, impairment, and negative health consequences (Prigerson et al., 1995; Prigerson et al., 1999a). Studies have documented chronic sleep disturbance (Germain et al., 1995; Hardison et al., 1995) and disruption in daily routine (Monk et al., 2006). People with complicated grief have been found to be at increased risk for cancer, cardiac disease, hypertension and substance abuse. (Szanto et al., 2006).

Risk factors for complicated grief have not been well studied. However, individuals who have a history of difficult early relationships and lose a person with whom they had a deeply satisfying relationship seem to be at risk. Additionally, those with a history of mood or anxiety disorders, those who have experienced multiple important losses, have a history of adverse life events and whose poor health, lack of social supports, or concurrent life stresses have overwhelmed their capacity to cope, may be at risk for complicated grief (Shear and Mulhare, 2008).

Some studies have examined deeply the relationship between CG and other DSM-IV-TR disorders, showing that this condition is distinct from depression

and post-traumatic stress disorder (Prigerson et al., 1997), even thought rates of comorbidity with these conditions are high. CG is also often associated with panic and bipolar disorder (Piper et al., 2001).

Some studies showed that subjects with CG report a higher rate of suicidal ideation than bereaved people without this condition (Szanto et al., 1997; Prigerson et al., 1999b;Leverich et al., 2003; Latham and Prigerson, 2004).In relation to this important finding, Shear et al. have deeply investigated the effect of a CG on bipolar subjects, showing that this condition is associated with elevated rates of panic disorder comorbidity, with a higher rate of lifetime suicide attempts and with greater functional impairment (Simon et al., 2005).

An interesting unanswered question is why one person develops complicated grief, while another suffers from major depression or post-traumatic stress disorder in the wake of a loss.

1.3 Relationship between Separation

anxiety and Complicated Grief

To the best of our knowledge the relationship between loss, complicated grief and separation anxiety has not been deeply investigated. There are two main theoriesthat explore the relationship between complicated grief and separation anxiety.

The first hypothesis, suggested by Prigerson, maintains that the vulnerability of a person to develop a complicated grief is rooted in disorders of attachment, particularly a dismissing attachment, frequently associated with symptoms of separation anxiety in childhood. (Vanderwerker et al., 2006). Subjects with symptoms of CSAD that persist into adulthood might have more problems with grief following a loss and might have an increased risk to developacomplicated grief and could more likely present the onset of several anxiety disorders such as panic disorder with primary panic attacks and/or an onset of a separation anxiety disorder in adulthood with secondary panic attacks.

The second hypothesis suggests a direct relationship between Complicated grief and ASAD. Manicavasagar et al. describe a series of clinical cases that reported an onset of adult separation anxiety following an important loss suggesting that this may be one pathway to developing the adult condition in the

absence of childhood disorder(Manicavasagar et al., 1997; Manicavasagar and Silove, 1997).In fact recent epidemiological data indicate that, surprisingly Separation Anxiety disorder is more prevalent in adults than in children and that the majority of adult cases (77%) had first onset directly in adulthood.

The relationship between CG and separation anxiety could be particularly significant in subjects with bipolar disorder, a condition that in literature results associated both with CG (Simon et al., 2005) and with separation anxiety symptoms both in childhood and in adulthood (Pini et al., 2005).

2. Sperimental Study

2.1 Aim of the Study

The purpose of this study is to report on a systematic analysis of the relationship between separation anxiety and complicated grief in a large cohort of patients with mood or anxiety disorders and the effect of these conditions on individual’s quality of life.

2.2 Methods

Sample

Participants were recruited in adult psychiatric outpatient clinics of four University Departments of Psychiatry (Pisa, Rome, Bari and Naples) between January 2007 and October 2009. The four centers have similar characteristics and represent tertiary care academic centers specializing in the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders. Patients with psychotic disorders or substance use disorder before the index assessment were excluded.

The study sample included an overall group of 454 consecutive adult psychiatric outpatients with Axis I anxiety and/or mood disorders as a principal diagnosis. One hundred and fifty-two (33%) patients were diagnosed with major depressive disorder and 162 (35%) with bipolar disorder (78 with bipolar I disorder, 84 with bipolar II disorder). Overall, 140 (31%) patients had an anxiety disorder (panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia) as their principal diagnosis. 93 patients with bipolar disorder (57%) and 79 subjects with major depressive disorder (52%) had at least one comorbid anxiety disorder.

Of the total cohort of 454 patients with mood and anxiety disorders, 219 (48%) were categorized as not having separation anxiety in adulthood or in childhood (NO-SAD); 198 subjects have a diagnosis of ASAD (43%), and 139 subjects a diagnosis of CSAD (30%); of those with ASAD, 89 (52%) have an history of CSAD. Of the total cohort 105 subjects (23%) endorse criteria for Complicated Grief.

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and study design was approved by the University of Pisa Ethics Committee. All subjects were informed of the nature of the study and they provided written informed consent prior to their participation. Interviews were performed by experienced residents in psychiatry. Subjects completed self-report questionnaires and structured clinical interviews over 2 days.

Diagnostic assessment

All subjects were assessed with the structured clinical interview for diagnostic and statistical manual (IV edition) axis I disorders (First et al., 2002) to establish DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis and psychiatric comorbidity.

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1960) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (Young et al., 1978) were used to assess severity of depression and mania, respectively. Anxiety was assessed by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1960) and the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (Shear et al., 1997).

Separation anxiety assessment

We conducted clinical interviews for adult and childhood history of separation anxiety using the Structured Clinical Interview for Separation Anxiety Symptoms (SCI-SAS) (Cyranowski et al., 2002). This semi-structured interview evaluates each of the 8 DSM-IV criterion symptoms of separation anxiety, separately for childhood (SCI-SAS-C) and adult symptoms (SCI-SAS-A). Each item was scored ‘0’(‘not at all’), ‘1’ (‘sometimes’), ‘2’ (‘often’) or ‘?’ (‘don’t recall’). In keeping with the DSM-IV guidelines, endorsement of three or more of

the eight criterion symptoms (symptoms rated as ‘2’ (‘often’) was used as a threshold to determine categorical (yes/no) diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder in childhood and adulthood. In addition, criteria B (i.e., duration of at least 4 weeks) and C (i.e., clinically significant distress or impairment in social, academic, occupational or other important areas of functioning) had to be met. Scores on the eight items of each subscale were also summed to produce a continuous measure of separation anxiety symptoms (range for each subscale = 0–16).

We further assessed separation anxiety using self-report questionnaires. The Separation Anxiety Symptom Inventory (SASI) (Silove et al., 1993) is a 15-item self-report inventory, developed to assess adult report of separation anxiety experienced during childhood. A total score is obtained adding single item scores and a square root transformation performed. Hence, a raw score of 16 generates a transformed score of 4, whereas a score of 9 transforms into a score of 3. The SASI total score is used after squared root transformation. This questionnaire has good psychometric properties, including high internal consistency and test–retest reliability. The Adult Separation Anxiety Checklist (ASA-27) (Manicavasagar et al., 2003) is a 27-item inventory which rates symptoms of adult separation anxiety. This scale has been shown to display good internal reliability as well as concurrent validity with clinical assessments of ASAD.

Complicated Grief assessment

Complicated grief was assessed by the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) (Prigerson et al., 1995). This instrument was developed to assess severity of grief reactions. Subjects were asked to report the frequency (0=‘never’; 1=‘rarely’; 2=‘sometimes’; 3=‘often’; 4=‘always’; total scale range 0-76) with which they currently experienced each of the 19 items exploring their emotional, cognitive and behavioral states. Complicated grief was diagnosed for participants with a score greater than 25 on the ICG at least 6 months after the death of a loved one and with endorsement of grief as their primary problem. The ICG has good psychometric properties including good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.94) and test-retest reliability(0.80).

Level of functioning

The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) was developed to assess functional impairment in three inter-related domains: work/school, social and family life (Sheehan, 1983). The SDS is a brief self-report. The patient rates the extent to which work/school, social life and home life or family responsibilities are impaired by his or her symptoms on a 10 point visual scale (range = 0–10; none

= 0, mild = 1–3, moderate = 4–6, severe = 7–9, very severe = 10). The 3 items can also be summed into a single dimensional measure of global functional impairment that rages from 0 (unimpaired) to 30 (highly impaired). This scale has an excellent internal consistency (cronbach’s alpha=0.89) and good test-retest reliability.

MOOD-SR

The MOODS-SR questionnaire, developed in English and Italian, is focused on the presence of manic and depressive symptoms, traits and lifestyles that may characterize the ‘temperamental’ affective deregulation that make up both fully syndromal and sub-threshold mood disturbances. The latter include symptoms that are either isolated or clustered in time and temperamental traits that may be present throughout the individuals lifetime. The MOODS-SR consists of 161 items coded as present or absent for one or more periods of at least 3-5 days in the lifetime. Items are organized into 3 manic and 3 depressive domains each exploring mood, energy and cognition, plus a domain that explores disturbances in rhythmicity and in vegetative functions, including sleep, appetite and sexual function. The sum of the scores on the three manic domains constitutes the score for the manic component and that for the three depressive domains constitutes

that of the depressive component. MOOD-SR has been shown to have good psychometric properties with good internal consistency (0.79-0.92) and good test-retest reliability (r=0.93-0.94)

2.3 Statistical Analyses

The mean values of continuous variables(±SD) such as age, and scale scores were compared between groups using ANOVA. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed by using Tukey's test.

Comparisons of categorical variables between groups were conducted using Chi squares with Bonferroni corrections. Strength of association between ASAD and CG are reported as Odds Ratios (OR) derived from logistic regression analyses using CG (ICG total score greater than 25) as the dependent variable and Axis I mood or anxiety disorder diagnoses and CSAD or ASAD as independent variables. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 16.0 (SPSS INC., 2007).

2.4 Results

Clinical correlates of adult separation anxiety

disorder

Of the total cohort of 454 patients with mood and anxiety disorders, 219 (48%) are categorized as not having separation anxiety in adulthood or in childhood; 198 (43%)subjects have a diagnosis of ASAD, and 139 (30%)subjects met the criteria for CSAD; of those with ASAD, 102 (52.0%) report an history of separation anxiety in childhood while 94 (48%) have an onset of the disorder directly in adulthood.

As shown in Table 1, women are more likely than men to present ASAD (p=.008). There are no other demographic differences between those with and without ASAD. Not surprisinglyASADresult associated with CSAD (p=.000) and with panic disorder with (p=.000) and without agoraphobia (p=.003). There are not association between ASAD and the frequency of occurrence of otherDSM-IV-TR axis I disorders. The presence of ASAD correlates with higher total scores in the Inventory of complicated grief (p=.000) and also with the presence of CG (Inventory of complicated grief total score>25) (p=.002).

Clinical correlates of Complicated Grief

Of the total cohort of 454 patients, 105 subjects (23%) of our sample met criteria for CG; of those, 59 patients (56%) met criteria for ASAD (p=.002) and 37 (36%) for CSAD.Surprisingly, as shown in Table 2,CG results associated only with ASAD (p=.002) and not withCSAD neither with any other DSM-IV-TR disorder.

Logistic regression analysis confirms the specific association between CG and ASAD after controlling for the effect of other mood and anxiety diagnoses (β=.658, p=.008, OR=1.931, 95%CI 1.188-3.138) (Table 3.).

Relationship between Complicated Grief and

Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder

We observed that the presence of CG influences various clinical features of subjects with ASAD (Table4); particularly CG is associated with higher mania (YMRS total score: p=.011) and depressive symptoms (HAM-D total score: p=.014).

The presence of CG in subjects with ASAD have not effect on the frequency of occurrence of other DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders even though

patients with both ASAD and CG are more likely to report bipolar I disorder symptoms (P=.040).

Table 5 compares scores on the ICG and the SDS subscales among the four subgroups: ASAD and CG, ASAD without CG, CG without ASAD, no ASAD and no CG.

Post-hoc tests demonstrate that subjects with CG and ASAD returned higher total scores on the ICG compared to those with CG and no-ASAD (p=.000). Co-occurrence of ASAD and CG is associated with greater impairment in quality of life compared to those without ASAD and without CG (SDS total score p=.000, Social impairments: p=.000, work/school impairments p=.002, family life impairments: p=.005; lost days of work in the last week: p=002; days of low efficiency at work: p=.000). The subgroup with both ASAD and CG shows higher levels of impairment than the subgroup with CG without ASAD (SDS total score p=.008; social impairment p=.003) and the subgroup with ASAD without CG (lost days of work in the last week p=.040 ; days of low efficiency at work p=.027). Subjects with only ASAD present greater impairments in quality of life compared to those without both ASAD and CG (SDS total score p=.029, work/school impairment p=.004,social impairment p=.031).

Finally we comparethe age of onset of ASAD and CG; the mean age of onset of ASAD is 15.49±12.44 while the mean age of development of CG is 33.60±12.34. 88% of the subjects with ASAD and CG reported first the onset of ASAD and only 12% of these subjects reported that the development of CG anticipate the onset of ASAD.

Complicated Grief and Bipolar disorder

In the subgroup of subjects with bipolar disorderCG continues to be associated only with ASAD (p=.002) and not with CSAD (p=.060) neither with any other DSM-IV-TR disorder.

In Table 6 we investigate the effect of CG in subjects with bipolar disorder; bipolar patients with CG present a more severe simptomatology of mood disorder: particularly CG was associated with higher mania (YMRS total score: p=.026) and depressive total scores (HAM-D total score: p=.004) and with more severe lifetime bipolar symptoms as measured by MOOD-SR (MOOD total score: p=.000; MOOD depressive tot score: p=.000, MOOD mania tot score: p=000).

Furthermore patients with CG present a more severe anxiety symptomatology associated with bipolar disorder; particularly they show higher

anxiety levels (HAM-A: p=.005), more panic attacks in the last month (p=.006) and more severe separation anxiety symptoms (ASA-27: p=.000).

Finally bipolar subjects with CG reported higher level of lifetime suicidal ideation (p=.027) and an higher number of suicide attempts (p=.029); in addition co-occurrence of CG and ASAD comprises a sub-population of bipolar patients at very high risk of suicidality (60% CG with ASAD vs 40% CG without ASAD vs 40% CG with panic disorder 20% no CG) (Fig.1).

3. Discussion

We report the results of a study conducted to evaluate the association between complicated grief and separation anxiety disorder.

We found that 25% of participants of the study reported a CG; this prevalence of lifetime CG is similar to rates reported in general psychiatric outpatient sample (Simon et al., 2005). The average time since the loss in the CG sample is about ten years, indicating that these patients had long-term complicated grief.

To the best of our knowledge, only one study investigated the association between separation anxiety and complicated grief,focusing on childhood separation anxiety disorder (Vanderwerker et al., 2006). Vanderwerker found that subjects with a history of separation anxiety in childhood are more likely to report complicated grief in adulthood. They hypothesized that the vulnerability to suffer from severe grief and to develop complicated grief following a loss, is rooted in disorders of attachment, particularly ”dismissing attachment”, which are frequently associated with symptoms of separation anxiety that persist from childhood to adulthood. These authors did not take into account the possibility that separation anxiety could originate in adulthood.

Interestingly, our data demonstratethat complicated griefis specificallyassociatedwith adult separation anxiety disorder and is not correlated withchildhood separation anxiety disorder;this is consistent with the result from a small pilot study we did but did not publish. In addition, comparing the different patterns of attachment and CG, the only relevant result was the association between secure attachment and the absence of CG (Data not shown).

Our results are consistent with the hypothesis of Manicavasagar and Silove of a possible onset of separation anxiety directly in adulthood after a stressful life events, like an event of loss or a bereavement (Manicavasagar and Silove, 1997).

To better investigate the relationship between complicated grief and separation anxiety, we have focused our attention on subjects with bipolar disorder, a condition that in literature results associated both with CG (Simon et al., 2005) and with ASAD (Pini et al., 2005). First at all we found that also in this subgroup of patients complicated grief results associated only with ASAD, and not with CSAD neither with other psychiatric disorder.

Furthermore bipolar subjects with CG present a more severe symptomatology of both bipolar and comorbidity anxiety disorder; particularly these patients show severe mania and depressive symptoms, a severe lifetime bipolar symptomatology and high levels of anxiety symtomatology. In bipolar subjects, CG results associated with separation anxiety symptoms and with an

high frequency of panic attacks but not with panic disorder, agoraphobia or other anxiety disorders.These data suggest that in bipolar subjects with CG,panic attacks could be secondary to ASAD and not correlated with a primary panic disorder.

A lot of studies showed that subjects with a complicated grief report a higher rate of suicidal ideation than bereaved people without this condition (Szanto et al., 1997; Prigerson et al., 1999; Leverich et al., 2003;Latham and Prigerson, 2004).In particularly Shear et al. have investigated the effect of CG in bipolar subjects, showing an independent and additive association of panic disorder comorbidity and CG with lifetime suicide attempts and suggesting that the co-occurrence of these conditions comprises a sub-population of bipolar patients at very high risk of suicidality and often unrecognized.In our sample the presence of CGin bipolar subjects seems strictly associated with an higher number of lifetime suicide attempts and with a more severe suicidal ideation;however the additive association is not between CG and PD (40% of subjects with a lifetime history of suicide attempts) but between CG and ASAD (60% of subjects).

Finally subjects with ASAD and CG endorse higher levels of functional impairment than those with only one of these conditions (ASAD only or CG only). Moreover, the influence of CG and ASAD on impairment remained

significant controlling for other co-occurring mood or anxiety disorders which were similarly distributed in the four comparison groups.

The limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. The results regarding the diagnosis of childhood separation anxiety disorder are based on retrospective reports made by adults. The potentially distorting influence of retrospective recall bias cannot be completely ruled out in interpreting these reports. However SCI-SAS-C was found to have strong psychometrics properties including good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.79) and convergent and discriminant validity.Although we found some important associations between separation anxiety and other clinical features, we could not determine the direction of causality. Nevertheless, these results suggest that the association between ASAD and CG is particularly strong. Finally, the lack of data concerning personality and temperamental characteristics did not allow us to investigate whether associations between CG and adult separation anxiety might be mediated by these factors. Further longitudinal studies are necessary to determine this relationship.

In summary, we found that in our sample of psychiatric outpatients with mood and anxiety disorders,complicated grief is specifically associated with adult separation anxiety disorder. Co-occurrence of these two conditions was associated with high levels of functional impairment.

Furthermore in bipolar subjects, CG determinesaworsening in the symptomatology of both bipolar and comorbidity anxiety disorder;CG results associated with separation anxiety symptoms and with an high frequency of panic attacks but not with panic disorder suggesting that in bipolar subjects with CG,panic attacks could be secondary to ASAD and not correlated with a primary panic disorder.

Finally bipolar subjects with CG present an higher risk of suicidality, expecially if ASAD is in comorbidity with those diagnosis.

However, further studies are warranted to investigate in more detail possible mediating factors in the putative relationship between ASAD, CG and other mood and anxiety disorders.

4. References

American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders, 4th Ed, Revised Version. American Psychiatric Press:

Washington, DC.

Auster T, Moutier C, Lanouette N, 2008. Bereavment and Depression : implications for diagnosis treatment. Psychiatr. Ann. 38, 655-61.

Bartholomew K., Horowitz LM., 1991. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 226-44.

Bonanno GA., Kaltman S., 2001. The varieties of grief expirience.Clin.

Psychol. Rev. 21:705-34.

Cyranowski JM., Shear MK., Rucci, P., Fagiolini A., Frank E., Grochocinski VJ., Kupfer DJ., Banti S., Armani A., Cassano GB., 2002. Adult separation anxiety: psychometric properties of a new structured clinical interview. J.

Psychiatr. Res. 36, 77–86.

EngelGL., 1961. Is grief a disease? A challenge for medical research.

First MB., Spitzer RL., Gibbon M., Williams JBW. 2002. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P). (ed. Biometrics Research). New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York.

Germain A, Caroff K, Buysse DJ., 2005. Sleep quality in complicated grief. J

Trauma Stress. 18:343–346.

Hardison HG, Neimeyer RA, Lichstein KL. 2005. Insomnia and complicated grief symptoms in bereaved college students. Behav Sleep Med. 3:99–111.

Hamilton M. 1959. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med

Psychol. 32:50–55.

Hamilton M. 1960. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry. 23:56–62.

Klein DF. 1980. Anxiety reconceptualized. Compr Psychiatry. 21:411–427.

Latham AE, Prigerson HG. 2004. Suicidality and bereavement: complicated grief as psychiatric disorder presenting greatest risk for suicidality. Suicide Life

Threat Behav. 34(4):350-62.

Factors associated with suicide attempts in 648 patients with bipolar disorder in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network.J Clin Psychiatry. 64(5):506-15.

Lewinsohn PM, Zinbarg R, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn M, Sack WM. 1997. Lifetime comorbidity among anxiety disorders and between anxiety disorders and other mental disorders in adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 11:377–394.

Melhem NM, Rosales C, Karageorge J, Reynolds CF 3rd, Frank E, Shear MK. 2001. Comorbidity of axis I disorders in patients with traumatic grief.. J Clin

Psychiatry. 62(11):884-7.

Manicavasagar V., Silove D., Curtis J. 1997. Separation Anxiety in adulthood: A phenomenological investigation. Compr. Psychiatry. 38, 274-282.

Manicavasagar V., Silove D. 1997. Is there an adult form of separation anxiety disorder? A brief clinical report. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 31 2, 299-303.

Manicavasagar V., Silove D., Curtis J., Wagner R. 2000. Continuities of separation anxiety from early life into adulthood. J. Anxiety Disord;4, 1–18.

Manicavasagar V, Silove D, Wagner R, Drobny J., 2003. A self report questionnaire for measuring separation anxiety in adulthood. Compr Psychiatry; 44:146–153.

Middleton W, Burnett P, Raphael B, Martinek N. 1996. The bereavement response: a cluster analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 169(2):167-171.

Monk TH, Houck PR, Shear MK., 2006. The daily life of complicated grief patients - what gets missed, what gets added? Death Stud. 30:77–85.

Otto MW, Pollack MH, Maki KM et al. 2001. Childhood history of anxiety disorders among adult with social phobia: rates, correlates, and comparisons with patients with panic disorder. Depress Anxiety. 14:209–213.

Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y., 1998 The risk of early adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 55:56–64.

Pini S, Abelli M, Mauri M et al., 2005. Clinical correlates and significance of separation anxiety in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorder.7:370–376.

Pini, S., Abelli, M., Shear, K.M., Cardini, A., Lari, L., Gesi, G., Muti, M., Calugi, S., Galderisi, S., Troisi, A., Bertolino, A., Cassano, G.B., 2009. Frequency and clinical correlates of adult separation anxiety in a sample of 508 outpatients with mood and anxiety disorders. Acta. Psychiatr. Scand. 13:1-7.

Piper WE, Ogrodniczuk JS, Azim HF, Weideman. 2001. Prevalence of loss and complicated grief among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 52:1069-74

Prigerson, H.G., Maciejewski, P.K., Reynolds, C.F. 3rd, Bierhals, A.J., Newsom, J.T., Fasiczka, A., FranE., Doman, J., Miller, M., 1995. Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry

Res. 29;59, 65-79.

Prigerson, H.G., Bierhals, A.J., Kasl, S.V., Reynolds, C.F. 3rd, Shear, M.K., Day, N., Beery, L.C., Newsom, J.T., Jacobs, S., 1997. Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. Am. J. Psychiatry. 154, 616-23

Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs SC., 1999a. Consensus criteria for traumatic grief. A preliminary empirical test. Br J Psychiatry. 174:67–73.

Prigerson HG, Bridge J, Maciejewski PK., 1999b. Influence of traumatic grief on suicidal ideation among young adults. Am J Psychiatry. 156:1994–1995.

Sheehan, D.V., 1983. The Anxiety Disease. New York: Scribner’s.

Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH et al. 1997. Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. Am J Psychiatry. 154:1571–1575.

Shear, M.K., Shair, H., 2005. Attachment, loss and complicated grief. Dev.

Psychobiol. 47, 253-67.

anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Am.

J. Psychiatry. 163, 1074-1083.

Shear MK, Mulhare E., 2008 Complicated grief. Psychiatr Ann. 39:662–670.

Silove D, Manicavasagar V, O'Connell D, Blaszczynski A, Wagner R, Henry J. 1993. The development of the Separation Anxiety Symptom Inventiry (SASI).

Aust NZJ Psychiatry.27:477–488.

Silove D, Manicavasagar V, O'Connell D, Morris-Yates A., 1995. Genetic factors in early separation anxiety: implications for the genesis of adult anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 92:17–24.

Simon NM, Pollack MH, Fischmann D., 2005. Complicated grief and its correlates in patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 66:1105–1110.

SPSS Inc. SPSS for Windows, Rel. 16.0., 2007 Chicago: SPSS.

Szanto K, Prigerson H, Houck P, Ehrenpreis L, Reynolds CF 3rd. 1997. Suicidal ideation in elderly bereaved: the role of complicated grief. Suicide Life

Threat Behav. 27:194-207.

Szanto K, Shear MK, Houck PR., 2006. Indirect self-destructive behavior and overt suicidality in patients with complicated grief. J Clin Psychiatry. 67:23–29

Vanderwerker, L.C., Jacobs, S.C., Parkes, C.M., Prigerson, H.G., 2006. An exploration of associations between separation anxiety in childhood and complicated grief in later life. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 194, 121-3.

Wijeratne, C., Manicavasagar, V., 2003. Separation anxiety in the elderly. J.

Anxiety Disord. 17, 695–702.

Yeragani VK, Meiri PC, Balon R, Patel H, Pohl R., 1989. History of separation anxiety in patients with panic disorder and depression and normal controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 79:550–556.

Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA., 1978. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiat. 133:429–433.

Zisook, S., Shuchter, S.R., Sledge, P.A., 1994. The spectrum of depressive phenomena after spousal bereavement. J Clin Psychiatry. 55:29-36.

5. Tables

Table 1. Demographic and clinical correlates of adult

separation anxiety disorder (ASAD

†)

No ASAD

(n=256)

ASAD

(n=198)

Chi-square

p.

Gender (female)

159 (62%)

145(73%)

6.244

.008

Marital Status (married)

118 (47%)

90 (46%)

1.003

.800

Emloyment (employed)

117 (48%)

89 (45%)

1.075

.783

Childhood separation

anxiety disorder

†37 (14%)

102 (52 %)

72.775

.000

Complicated Grief

46 (18%)

59 (30%)

8.787

.002

ICG total score

13,23± 12,37 19,16±17,62

4.20

(T-test)

.000

Axis I comorbidity‡

Panic Disorder

111 (43%)

113 (57%)

8.397

.003

Agoraphobia

58(22%)

75 (38%)

12.387

.000

Obsessive compulsive

disorder

49 (19%)

46 (23%)

1.130

.172

Major Depression

95 (37%)

57 (28%)

3.471

.039

Bipolar Disorder

90 (35%)

72 (36%)

.071

.433

† assessed by Structured Clinical Interview for Separation Anxiety Symptoms in Adulthood (SCI-SAS-A) and in Childhood (SCI-SAS-C)

Table 2.Relationship between CG and the frequency of

Psychiatric Disorders

CG

(N=105)

No CG

(N=349)

Chi-Square

P

Childhood Separation

Anxiety Disorder

†37 (36%)

102 (29%)

1.393

.145

Adulthood Separation

Anxiety Disorder

†59 (56%)

139 (40%)

8.787

.002

Axis I comorbidity‡

Panic disorder

50 (48%)

174(50%)

0.162

.386

Panic disorder plus

agoraphobia

29 (28%)

104(30%)

0.168

.390

Obsessive-compulsive

disorder

22 (21%)

73 (21%)

0.000

546

Major depression

32 (30%)

120 (34%)

0.553

.267

Bipolar disorder

40 (38%)

122 (35%)

0.346

.317

CG: complicated grief (Inventory of Complicated Grief total score >25)

† assessed by Structured Clinical Interview for Separation Anxiety Symptoms in Adulthood (SCI-SAS-A), Structured Clinical Interview for Separation Anxiety Symptoms in Childhood (SCI-SAS-C)

Table 3. Logistic regression analyses using CG as the

dependent variable and Axis I mood or anxiety disorder

diagnoses and CSAD or ASAD as independent variables

B

P

Odds

Ratio

95% of

confidence

interval

Adult separation

anxiety disorder

†.658

.008

1.931

1.188 - 3.138

Childhood separation

anxiety disorder

†.032

.903

1.033

.617 - 1.729

Obsessive

compulsive disorder

‡-.147

.620

.863

.482 - 1.546

Panic Disorder

‡-.216

.377

.806

.499 - 1.301

Bipolar Disorder

‡.068

.814

1.070

.609 - 1.879

Major Depression

‡-.121

.686

.886

.492 - 1.594

Constant

-1.376

.000

.253

CG: Complicated grief (Inventory of Complicated Grief total score >25)

† assessed by Structured Clinical Interview for Separation Anxiety Symptoms in Adulthood (SCI-SAS-A), Structured Clinical Interview for Separation Anxiety Symptoms in Childhood (SCI-SAS-C)

Table 4: Effect of complicated grief on clinical correlates of

subjects with adult separation anxiety disorder

ASAD

Without CG

(n=139)

ASAD

With CG

(n=59)

Chi-square

P

CSAD

71 (51%)

31 (53%)

.065

.461

Panic Disorder

83 (60%)

30 (51%)

1.329

.160

Agoraphobia

55 (40%)

20 (34%)

.449

.307

OCD

32(23%)

14 (24%)

.012

.525

Major Depression

43(31%)

14 (24%)

1.049

.198

Bipolar Disorder

46 (33%)

26 44%)

2.156

.096

Bipolar disorder I

18 (13%)

14 (24%)

3.552

.040

Bipolar disorder II

28 (20%)

12 (20%)

.001

.558

F value

HAM–Deptotal score

11.19±7.02

14.10±8.36

6.197

.014

HAM–Anxtotal score

12.04±7.87

14.71±8.07

2.165

.145

YMRS total score

1.54±2.79

2.74±3.34

6.615

.011

PDSS total score

9.27±5.63

10.90±7.56

1.572

.213

ASAD with CG: Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder with complicated grief ASAD without CG: Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder without complicated grief HAM-Dep total score: Hamilton depression total score

HAM-Anx total score: Hamilton anxiety total sore

YMRS total score: Young Mania Rating Scale total score PDSS total score: panic disorder severity scale total score

Table5: Effect of complicated grief (CG) on clinical correlates of subjects with

and without adult separation anxiety disorder(ASAD)

No ASAD

No CG

(n=210)

CG

No ASAD

(n=46)

ASAD

No CG

(n=139)

ASAD

and CG

(n=59)

F value

Tukey’s post hoc tests*

SDS total

score

13.79±9.23

13.85±7.49 16.85±7.87 20.97±7.04

7.641

ASAD+CG vs No ASAD/No CG: p.000 ASAD+CG vs CG only:p.008 ASAD only vs No asad/no CG: p.029Work-school

interferenc

e

4.53±3.61

4.65±3.44 5.73±3.36 7.00±3.01

5.694

ASAD+CG vs No ASAD/No CG : p.002ASAD only vs No asad/no CG: p.004

Social

interferenc

e

4.82±3.34

4.44±3.11 5.97±3.00 7.37±2.98

7.540

ASAD+CG vs No ASAD/No CG : p.000 ASAD+CG vs CG only: p.003 ASAD only vs No asad/no CG: p.031Family life

interferenc

e

4.46±3.40

4.92±2.73 5.15±3.15 6.59±3.14

3.976

ASAD+CG vs No ASAD/No CG : p.005Work days

lost

1.52±2.64

2.19±2.93 1.96±2.61 3.45±2.90

4.440

ASAD+CG vs No ASAD/No CG: p.002ASAD+CG vs ASAD only: p.009

Work

daysunprod

uctive

1.97±2.75

2.76±3.11 2.71±2.72 4.32±2.78

6.278

ASAD+CG vs No ASAD/No CG : p.000 ASAD+CG vs ASAD only:p.017

Table 6: Effect of complicated grief on clinical correlates of

subjects with bipolar disorder

BD

without CG

(n=122)

BD

with CG

(n=40)

F value

P

HAM – Dep

11.10±7.77

15.41±8.77

8.483

.004

YMRS

2.19±2.93

3.51±3.89

5.040

.026

HAM – Anx

8.55±7.10

15.06±9.42

8.604

.005

PDSS

7.04±5.60

10.33±8.63

3.839

.054

ASA-27

27.95±13.76

40.64±14.71

24.236

.000

Number of panic

attacks (last month)

2.19±3.36

6.88±10.02

8.007

.006

Lifetime suicidal

ideation

42 (45%)

23 (66%)

4.513

.027

Lifetime suicide

attempts

20 (21%)

14 (40%)

4.606

.029

MOOD-SR

total score

71.76±24.85

96.31±24.51

25.065

.000

MOOD-SR

depression total score

33.82±14.78

45.54±13.41

16.796

.000

MOOD-SR

maniac total score

23.18±10.91

31.37±10.88

14.286

.000

BD with CG: Bipolar Disorder with complicated grief BD without CG: Bipolar Disorder without complicated grief HAM-Dep total score: Hamilton depression total score HAM-Anx total score: Hamilton anxiety total sore

YMRS total score: Young Mania Rating Scale total score PDSS total score: panic disorder severity scale total score

Figure 1: Effect of complicated grief and separation anxiety disorder

onsuicidality of subjects with bipolar disorder

NO CG: no complicated grief, no ASAD CG: complicated grief without ASAD

CG + PD: complicated grief and panic disorder 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90%

Lifetime Suicide attempts Lifetime Suicidal Ideation

NO CG CG CG + PD CG + ASAD